CCR Special 8 — Morrow Designs

Morrow Designs, Inc., the company founded by George Morrow and his wife in 1979, was part of the early wave of small manufacturers that produced microcomputers for the business market. Morrow Designs, Osborne Computer Corporation, Kaypro Corporation, and Vector Graphic all basically followed the same playbook: Sell a pre-assembled computer bundled with Gary Kildall’s CP/M operating system and other business software, such as a word processor and a spreadsheet.

The short version of history tells us that these early companies all withered away after IBM debuted its own Personal Computer and made Microsoft’s PC-DOS (i.e., MS-DOS) the new operating system standard. But there were, of course, other factors involved in each company’s demise. In the case of Morrow Designs, the biggest reason for the company’s failure was George Morrow himself.

That might sound harsh, but of the four companies I mentioned, Morrow Designs was the only one that never went public or took substantial venture capital funding upfront. So this wasn’t a case where the company failed because of VC meddling or a sudden collapse in the stock price. George Morrow valued his independence above all else and he was openly critical of the role that money played in the computer industry.

Morrow’s own background was that of an engineer and self-described “tinkerer.” In that sense he was much like Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, whom he knew as a fellow member of the famous Homebrew Computer Club. Conversely, Morrow was the polar opposite of Wozniak’s business partner, Steve Jobs, at least in terms of their public personas. Jobs always played the role of the optimist, championing the growth of a mass market for personal computing. Morrow was a pessimist. You saw this to some degree in his Computer Chronicles commentaries. And in reviewing his writings and interviews from the period when Morrow Designs was active, Morrow made it clear he didn’t think there was really a mass market for computers in the mid-1980s–which probably goes some way to explaining why his company struggled.

“The Hell With You”

George Clayton Morrow was born in Detroit on January 30, 1934. His family was in the restaurant business–Morrow’s father owned a drive-in near San Francisco and his uncle ran a luncheonette. Morrow described himself as a teenage delinquent to authors Robert Levering, Michael Katz, and Milton Moskowitz, who profiled Morrow for their 1984 book, The Computer Entrepreneurs, which also featured Gary Kildall. Morrow said he was a D-student who got himself kicked out of school at the age of 16.

After his first business venture–stealing white-wall tires from cars around the Bay Area and “reselling” them in southern California–landed him before a judge, Morrow faced an Armin Tamzarian-style choice: Go to jail or enlist in the Army. Morrow opted for the latter and briefly served in the Korean War before the signing of the 1953 armistice.

Morrow spent two years in the Army altogether, serving in posts around Asia, before returning to the United States and following in the family tradition by becoming a short-order cook. At the age of 27, Morrow went back to school. Thanks to the GI Bill, he worked his way from community college into Stanford. While at Stanford, Morrow met and married his wife, Michiko Jean, and they eventually had three children.

Morrow later recounted for Computer Entrepreneurs that despite his age, he was not very mature when it came to dealing with criticism or authority figures:

A mechanical engineering major, [Morrow] took his one required course in modern physics and realized he still didn’t know anything about it. “I need more physics,” he told his advisor.

“You need to finish your major and get out of school, so you can start earning money,” said the advisor. “You’re 30 years old. You’re an old man.” Then he added, “If I see any more physics courses on your card, I won’t sign it.”

“The hell with you,” was Morrow’s retort. He promptly changed his major to physics.

Morrow completed that degree in physics before pursuing graduate studies in mathematics, earning a master’s from the University of Oklahoma. He subsequently returned to California to pursue a doctorate in mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley, while also teaching calculus to undergraduate students.

Morrow never completed his doctorate. In 1968, he took a computer programming class at Berkeley and then spent the next seven years working as a programmer for the university’s business school, building computer analysis models and learning about hardware design. In 1975, Morrow left Berkeley and set up a consulting business. That didn’t last long, because as he told Computer Entrepreneurs, he “didn’t like solving problems someone else had set.”

It was also around this time that the Homebrew Computer Club began following the late 1974 release of the Altair 8800 microcomputer, which was based on the Intel 8080 CPU. According to Stan Veit, an early computer store owner and later the founding editor of the magazine Computer Shopper, Morrow and two other Homebrew members, Chuck Grant and Mark Greenberg, agreed to form a company to make expansion boards for the Altair. But once again, that didn’t last long. Veit said Morrow “had his own ideas of what he wanted to do, and the group split.” (Grant and Greenberg later started their own early computer company, NorthStar Computers, which lasted until 1984.)

Morrow then tried to build a board that would enable someone to program the Altair using a keypad as opposed to the switches that came with the machine. According to Veit, that project didn’t go anywhere either:

The CPU board was a good idea but was not a success because George had it programming in octal notation while the rest of the 8080 world was using Hex notation. Besides, the hobbyists liked to program by flipping switches.

Morrow’s next venture was with Bill Godbout, the owner of Godbout Electronics, which sold mail-order circuit boards and computer kits. Godbout hired Morrow to design a 16-bit computer kit. When that didn’t work out, Morrow designed memory boards instead. But he quickly tired of taking direction from Godbout, so he decided once again to strike out on his own.

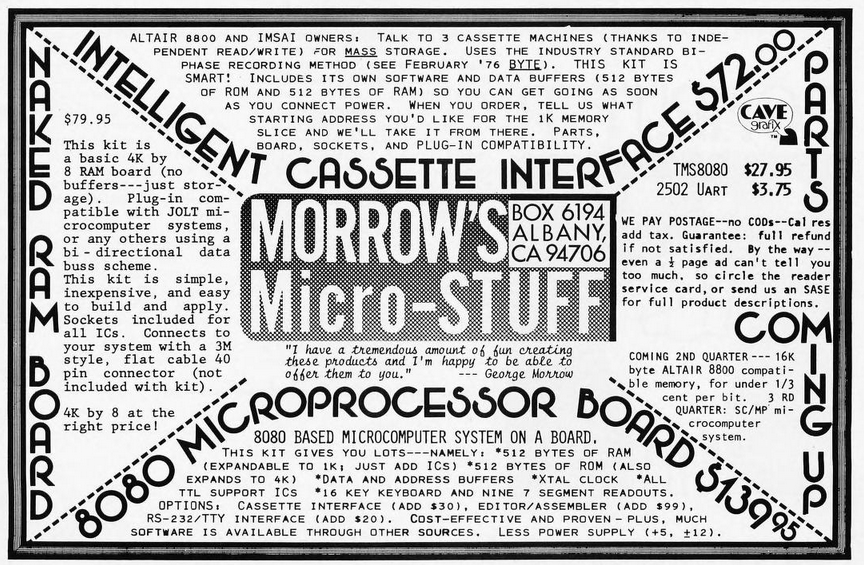

This is where Morrow Designs began, although that wasn’t the original name. Morrow and his wife didn’t actually incorporate their business until 1979, but George Morrow started selling his own mail-order circuit boards and computer components in early 1976. The first advertisement for “Morrow’s Micro-Stuff,” the original name of the business, appeared in the April 1976 issue of Byte (see below).

Morrow’s initial capital consisted of $6,000 in personal savings. He told Computer Entrepreneurs that the Byte ad led to $50,000 in sales by the end of 1976. By 1978, his home-based business reached $600,000 in sales. At that point the business hired its first employee and moved out of the Morrows’ home in Berkeley and into a small office in nearby Richmond. (From what I could tell the Richmond office was just another house.)

CBS vs. Morrow

In 1977, George Morrow decided to rename his business “Thinker Toys.” He told Tom Williams of The Intelligent Machines Journal in February 1979 that he picked that name based “on the idea that a computer system should be as easy to configure for different applications as a set of Tinker Toys.” Morrow was quick to clarify, however, that “his company was in no way affiliated” with Tinker Toys.

Unfortunately CBS Inc., which at the time owned Tinker Toys through a subsidiary, didn’t view Morrow’s “Thinker Toys” as a nice homage. So when Morrow filed his trademark for “Thinker Toys,” CBS objected. Although the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office upheld Morrow’s trademark, CBS appealed. In June 1983, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in favor of CBS and canceled Morrow’s trademark.

Circuit Judge Jack R. Miller, a former Republican senator from Iowa, wrote the panel’s decision. Miller rejected Morrow’s argument that because his customers were “by and large sophisticated, well-educated, technically oriented persons,” there was no risk of them confusing his circuit boards with children’s toys:

[Morrow’s] goods are not limited to any particular channels of trade or methods of distribution, nor to any particular end products. They are identified so broadly that they could include electronic components and circuit boards for computer games or video games. We are not persuaded that [Morrow] would always refrain from offering circuit boards for computer games or video games through the same channels of trade employed by [CBS] for its “TINKERTOY” products.

Basically, the CBS-held trademark covered games and toys. And given the “popularity of computer and video games,” Miller said it stood to reason that potential buyers of computers with “Thinker Toys”-branded components would likely believe they came from the same company that made “Tinker Toys.” Morrow argued this was unreasonable since the development costs–and prices–of the products he sold were too high to make them competitive against games and toys. In a prescient footnote, Miller retorted, “Advances in technology often convert the prohibitive undertakings of today into the profitable ventures of tomorrow.”

The Morrow Decision 1

The Morrows formally incorporated their business in 1979 as Morrow Designs, Inc., although the “Thinker Toys” name continued to appear in some advertisements until around 1981. Sometime in late 1981 or early 1982, Morrow Designs relocated again, this time to a manufacturing facility at 600 McCormick Street in San Leandro, California, which is in Alameda County.

The Morrow Designs business in the late 1970s was squarely focused on selling circuit boards and computer peripherals rather than pre-assembled systems. According to information provided by Morrow during the CBS litigation, Morrow Designs sold approximately 85 percent of its products wholesale to computer stores and equipment manufactures, while the remaining 15 percent were mail order sales, with about one-third of those purchases made by individual consumers.

Morrow Designs was a leading supplier of parts and expansion cards for the S-100 bus, an open-standards clone of the system bus used on the Altair 8800. Prior to the introduction of the IBM PC, the S-100 was the de facto architecture used by CP/M-based microcomputers. George Morrow was particularly interested in disk controllers and hard disk drives for the S-100 bus. Tom Williams recounted in his 1979 interview with Morrow:

Concerning the small business market, which is now the bread and butter of microcomputer manufacturers and dealers, Morrow sees the cost of hard disks coming within the reach of the small business customer. Floppy disks have, for some time, been a limitation of the usefulness of microcomputer systems; the increased storage capacity of the hard disks will give a great deal more flexibility to the small business user. The squeeze will come, he says, in the area of software.

Morrow decided to make the leap into computer manufacturing in 1981, when Morrow Designs launched the Morrow Decision 1, a microcomputer based on the S-100 bus and the Zilog Z80 microprocessor. The Z80 was an 8-bit CPU popular among early microcomputer manufacturers. John C. Dvorak, writing for InfoWorld in April 1981, said the Decision 1 “may become the superstar of the OEM market.” Morrow claimed it was the “fastest Z80 machine made” and could “easily outperform” a 16-bit computer.

Morrow was especially committed to the 8-bit architecture even as 16-bit processors–notably the Intel 8086, which came out in 1979–were starting to become commercially viable for microcomputers. Perhaps still smarting from his earlier failed attempt to build a 16-bit board for Bill Godbout, Morrow insisted his real reason for sticking with 8-bit was that he didn’t want to break compatibility with existing software. But there was definitely some hostility to the very idea of using a 16-bit processor. Bert Greeley, who said he worked for Morrow Designs during the development of the Decision 1, posted on Old-Computers.com that “George toyed with the 8086 but he was steadfastly against a 16-bit OS,” at least until after Greeley left the company in 1981. Morrow himself would later say, “Sixteen bits for the sake of 16 bits is an engineer’s approach to products,” which was a strange remark give that he was an engineer.

Although the Decision 1 came standard with CP/M, it was also perhaps the first “consumer” level microcomputer designed to use UNIX. Morrow Designs offered configurations of the Decision 1 that included a hard drive with Micronix pre-installed. Micronix was a UNIX-based operating system developed in-house at Morrow Designs. This was well before the days of BSD, so Morrow actually purchased a commercial license from Bell Labs for what was then Version 6 Unix. Apparently, you could still run CP/M programs on top of Micronix, which effectively created a multi-user CP/M system.

The Micronix version of the Decision 1 was not cheap. It cost $7,290 according to Old-Computers.com, no doubt due to the costs of licensing UNIX commercially in those days. For that reason, I don’t think the Micronix units sold very well. A 1982 price list from Morrow Designs omitted any mention of Micronix as an option for the Decision 1. By that point, the standard configuration–which came without a disk drive, keyboard or display–cost $2,395. A full setup with a 5.25-inch floppy disk and a 16 MB hard drive cost $5,400. A video display terminal, which included a green phosphor screen and a keyboard, cost an additional $595.

The Micro Decision and the Pivot

The IBM PC launched in August 1981, a few months after the Decision 1 came to market. Morrow Designs’ response was to launch the Morrow Micro Decision in 1982. The Micro Decision was partly based on the Decision 1 but abandoned the S-100 bus in favor of a single-board design similar to that of the IBM PC.

The Micro Decision came in a number of configurations. The basic model, known as the MD-1, came with one single-side 5.25-inch floppy disk drive. The intermediate model, the MD-2, added a second single-sided floppy drive. The top model, the MD-3, came with two double-sided drives.

The prices ranged from $1,145 for the MD-1 to $1,695 for the MD-3. As with the Micro Decision 1, the terminal was a separate $595 purchase. But the Micro Decision models all came with a bundle of included software on disk, including WordStar (word processor), LogiCalc (spreadsheet), and Correct-It (spell checker). The MD-3 also included a database manager, Personal Pearl.

Bundling a lower-end Z80 machine with business software was not a Morrow Designs innovation. Osborne and Kaypro did the same thing. Indeed, George Morrow later credited Adam Osborne with recognizing the importance of bundling, stating, “I watched what he did and figured that if a little software was good, a lot would be even better.”

Tom Wadlow reviewed the MD-3 model for the October 1983 issue of Byte. Wadlow said his biggest problem with the system was the Morrow-produced terminal. He “found the keyboard layout poor” and noted the terminal was “delivered unconfigured,” meaning the user had to program the basic characteristics during first use. That said, Wadlow said the green phosphor display was “crisp and clear.”

Wadlow also questioned some of Morrow’s bundled software choices, specifically LogiCalc and Correct-It, which he found lacked proper documentation and were not “suitable for novice users.” Overall, Wadlow concluded the Micro Decision “would make a good second computer for people who are familiar with CP/M systems or for those who have had experience with computers.”

On the other hand, Laurie Baggiani thought the Micro Decision was perfectly friendly for beginners. Writing for the May 1984 Creative Computing, Baggiani found the Micro Decision was the first low-cost system that made CP/M “less threatening” for new users:

One feature especially welcomed by neophytes is Morrow’s Micro Menu, a menu driven front end to CP/M 2.2, which provides a gradual introduction to the popular and somewhat legendary operating system. Described as “your road map through CP/M,’ the menu lets you access six of the applications programs provided with the unit, or select a utility menu for help in performing nine of the most common CP/M utilities.

Clear, concise, on-screen directions, make commands like formatting a disk, copying and renaming files, as easy as following a recipe–regardless of your level of computer expertise. Conveniently, too; once you become adept at working within CP/M, the menus can be deactivated, restoring the standard CP/M level of operation.

Contemporary accounts said the Micro Decision line sold well throughout 1983. Although success was relative when talking about a small company like Morrow Designs. Sypko Andrae, who edited the Morrow Owners’ Review–more on that in a moment–wrote at the time of Morrow Designs’ bankruptcy in March 1986 that there were a total of 40,000 Micro Decision machines sold. Apple, whom George Morrow considered a direct competitor in the small business computer market, sold 420,000 Apple II machines in 1983 alone. And sales of IBM PC and its compatibles topped 1.3 million that same year.

Undeterred by his comparatively small sales volume, George Morrow announced in late 1983 that he would soon offer a portable version of the Micro Decision. Morrow told Paul Freiberger of InfoWorld that he “has never been an enthusiast of portable computers,” but was driven to introduce one after seeking Kaypro’s model, which didn’t impress him.

Morrow Designs first displayed its portable machine–dubbed the Morrow Pivot–at the May 1984 COMDEX show in Atlanta. The Pivot shipped around November of that year. George Morrow made his first Computer Chronicles appearance at the end of the year to promote the computer.

I’m not sure why Morrow called it the “Pivot,” but perhaps it was a reference to the fact the portable represented a decisive shift away from CP/M. The Pivot was an MS-DOS machine. The base model, which included a single double-sided disk drive, initially retailed for just under $2,000.

By the time the Pivot came out at the end of 1984, Morrow Designs’ product catalog had exploded. There were newer versions of the Micro Decision, such as the MD3-P ($1,899), which had a built-in display, and the MD11, which came with an 11 MB hard drive and retailed for $2,595 without the display terminal. Morrow also decided to try his hand at UNIX again, this time with the Tricep, which was billed as a multi-user “supermicro” running UNIX System V and starting at $8,495. (I’m not sure the Tricep was ever actually sold, as I couldn’t find any reference to it outside of the Morrow Designs price sheet.) Morrow also continued to sell variants of the original Decision 1, as well as various peripherals such as printers and modems.

Quotations from George Morrow

In November 1984, George Morrow self-published Quotations from Chairman Morrow, which was essentially Twitter-before-Twitter in book form. This book was not sold commercially. Rather, Morrow Designs distributed it to the press and other attendees at the fall COMDEX show in Las Vegas. John C. Dvorak wrote the introduction.

I said in my introduction that George Morrow was a pessimist when it came to computers. Quotations provides a good deal of data to support my hypothesis. Morrow turned 50 in 1984 and his prose had a certain “old man yells at cloud” quality. Indeed, a lot of Morrow’s quotes were little more than insults and ad hominem attacks against specific groups within the industry. Here’s a small sampling:

- “Programmers are like rock stars. But with rock stars, at least you get to hear the song before you buy the record. A programmer spends six months tuning his instrument and, whether it works or not, you’re paying the whole time.”

- “Japanese accounts payable are like heroin; they get you hooked with 120-day payment plans.”

- “Money is the only lethal drug available on a non-prescription basis. Bankers are the druggists.”

- “If I had a business that relied on kids sticking quarters in a machine, I couldn’t sleep at night.”

- “Venture capitalists are like lemmings jumping on the software bandwagon.”

- “There’ll be a special place in hell for the tape back-up people.”

- “Lawyers. The worst parasites this country has produced.”

- “Anyone who trusts a programmer deserves what happens to him.”

- “Not everybody needs a computer. If a dealer sells one of my computers to the wrong person, my reputation and the dealer’s are on the line. Only two groups benefit–the phone company and United Parcel Service.”

In terms of his own business, Morrow reiterated his belief that bundling software and hardware in a relatively low-cost package was the way forward: “With bundled machines you can throw away the hardware and keep the software, and it’s still a good buy,” he wrote.

On the surface, that sounded like a very pro-consumer approach to the computer business. But in practice there were a lot of problems. As Tom Wadlow’s review of the MD-3 in Byte suggested, Morrow’s machines were not targeted at novice users. Bundling software didn’t help much if the customer couldn’t figure out how to use the programs. And Morrow Designs offered little in the way of actual support.

Now to be fair, computer manufacturers in this period typically relied on their distributors–authorized dealers such as computer stores–to provide the bulk of customer support. But as far as I can tell, Morrow Designs had no in-house support operation of any kind. Morrow outsourced some of its customer support to Xerox. But George Morrow himself championed user groups–not unlike the old Homebrew Computer Club–as the best way for users to find help.

To that end, Morrow Designs provided some funding to the Bay Area Micro Decision Users Association (BANDUA), established in 1983, to publish a national newsletter for Morrow Decision owners. The Morrow Owners’ Review, launched in April 1984, was editorially independent from Morrow Designs. But the company initially paid for the Review’s printing and mailing.

The Review was definitely not a Morrow mouthpiece. To the contrary, the newsletter amplified a lot of the ongoing problems that Morrow Decision customers had with obtaining support. The second issue of the Review, published in June 1984, described a BAMDUA-hosted forum featuring a panel of Morrow dealers as well as Morrow Designs president Bob Dilworth and Howard Fullmer, the company’s chief engineer. Peter Campbell, who wrote the account, said the Morrow representatives spent nearly an hour listening to complaints, particularly about poor documentation:

[Dilworth and Fullmer], reeling from the attack, defended [their] position with a shield of valid points. Most documentation is written by the software publisher, not Morrow. This is probably not the best way to do it, but economics dictate this procedure. To re-write all documentation would be very expensive. The NewWord [word processor] manual actually was written by Morrow, and it is a good one. But it cost $20,000 to produce. The cost of re-writing all the manuals would be prohibitive, and would make it necessary to raise the price of the computer. Morrow is probably the best buy in today’s market. We should not expect to pay $2,000 for a computer and then get $3,000 of hand holding.

The Morrow representatives also pointed out their machines were not sold by large retailers like ComputerLand. Again, it came down to economics. ComputerLand didn’t carry computers that came bundled with software: “They want their customers to buy all needed software from them, because that is where a lot of their profit is.”

It was easy to try and blame the retailers for being greedy. But Morrow Designs’ attitude was also a reflection of its core problem–the company consistently lacked sufficient capital to fully support its bloated product line. And once again, this fell directly at the feet of George Morrow. Jim Bartimo, a writer at InfoWorld, asked Morrow point-blank in an October 1984 interview if he needed additional funding to bring the Pivot to market. Morrow replied:

Well, I could always use some capital. Seeking funds? I guess we are.

I’m a little suspicious of money. You know we were going to go public last fall [in 1983] about this time, but we didn’t make it to the marketplace. And really it’s good that we didn’t. We wouldn’t have been able to take as much money out of the marketplace as Fortune [Computers], we wouldn’t have taken as much as Kaypro, and we’d have spent it all by now. We’d be in worse shape–the stock would have been down to $1.50. We’d have half a dozen stockholder suits. We’d probably be deeper in the bank then we are now, and this product wouldn’t be ready.

Morrow overcame his aversion to venture capital long enough to take $3.5 million in funding during 1983. But the Morrows still retained 72 percent control of Morrow Designs. George Morrow referred to his unwillingness to give up control as “entrepreneur’s sickness.” In Quotations, he actually credited Apple’s Steve Jobs for being “smart enough to see that he had to give away parts of his company to get the most talented people.”

Unfortunately, $3.5 million didn’t get you very far when it came to computer manufacturing. Morrow Designs was effectively a bootstrap operation for its entire lifespan. George Morrow told a BAMDUA meeting in January 1984 that he was smarting after a customer bounced a $95,000 check. “We’re still paying our bills,” he told the group, but he added that the aborted 1983 public offering had been expected to raise $25 million.

“I Don’t Care to Struggle Any Longer”

At the May 1985 COMDEX show in Atlanta, Morrow Designs announced what would be its final major product, the Pivot II. Like the original Pivot, the Pivot II was an MS-DOS portable computer with a built-in LCD screen. But the Pivot II’s screen was backlit.

Desperate for cash, Morrow Designs licensed the Pivot II design to two other companies, Osborne and Zenith Data Systems. The Zenith license proved to be fatal. The exact details are somewhat unclear to me, but essentially Zenith paid Morrow Designs an upfront licensing fee that did not include any per-unit royalties. Some accounts I’ve read said that Zenith offered Morrow Designs a choice between a license with or without royalties, and George Morrow chose the latter. But Wendy Woods’ Newsbytes reported on September 10, 1985, that Zenith “pulled its license after its corporate chiefs decided the licensing terms were too lenient.” This forced Morrow Designs to shut down production, as they were making the Zenith-licensed machines, and lay off half of the company’s 60 remaining employees. (Morrow Designs employed about 130 staffers at its height in 1984.)

To add insult to injury, Morrow Designs president Bob Dilworth and another key employee had left to join Zenith as general manager just a few weeks before this dispute arose. A week later, on September 17, Woods reported that the licensing dispute had been resolved “and a new contract signed.” The laid-off workers were brought back. But that proved to be a short-term respite.

Things finally came to a head in early 1986. The Internal Revenue Service was accepting bids for a $28 million contract to provide up to 18,000 portable computers to the agency’s auditors. IBM was considered the early front-runner. But the IRS only wanted bids for off-the-shelf machines that were actually on the market. IBM’s new portable wasn’t ready yet. So that opened the door for both Zenith and Sperry Corporation.

Zenith and Sperry both based their bids on the Morrow Pivot II design. Sperry actually planned to use Morrow Designs as its OEM if it won the bid, which would have been a lifesaver for George Morrow and his company. But the IRS ultimately went with Zenith. Morrow got the credit for designing the Zenith machine–known as the Z-171–but little else. Thanks to the revised licensing deal, Morrow Designs would not see any royalties or additional income from the IRS contract with Zenith.

Publicly, George Morrow told Wendy Woods that he was “justly proud” that his company’s design won the bid. And Morrow Designs planned to soldier on despite Sperry’s loss. On March 4, 1986, Morrow held a press conference in Palo Alto, California, to announce yet another new product–the Pivot XT, which was basically the Pivot II with a 10 MB hard drive. Barry Berghorn, who took over as Morrow Designs president a few months earlier following Bob Dilworth’s sudden departure, said the XT would ship by June 1986.

Well that didn’t happen, because three days later Morrow Designs collapsed. George Morrow didn’t have to answer to shareholders or venture capitalists, but he did have to answer to Union Bank of Los Angeles, which held $5 million in loans secured by Morrow Designs’ assets. Morrow and Berghorn met with the bank on March 7 and the outcome of that meeting was that Morrow Designs filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Berghorn announced his resignation that same day–he told Woods, “I don’t care to struggle any longer”–and Morrow Designs fired 23 of its remaining 35 employees.

While Chapter 11 often gives bankrupt companies a chance to reorganize and stay in business, Union Bank was having none of that. It moved quickly to liquidate Morrow Designs’ remaining assets. A public auction was held at the now-defunct company’s McCormick Street building in San Leandro on June 24, 1986. Sypko Andrae of the Morrow Owners Review provided a firsthand account:

Signs on yellow notepad paper showed the way inside the Morrow plant: “Sale starts here ->.” By 11 a.m. there was a small crowd assembled in Morrow’s former manufacturing hall. Everyone was leafing quickly through the 11-page auction catalog that listed over 700 lots, with a short description of what was in each lot. All of the hardware was laid out on tables and benches, an overwhelming amount: rows of ADM-20 terminals, stacks of MT70 terminals, which had been so hard to find up till now. How did Morrow hold on to all this stuff so long?

Everything went under the hammer: tool boxes, soldering irons, test equipment, Tektronics scopes, old pivots (model Is; there were no Pivot IIs anywhere), about 60 MD3s–with or without MT70 terminals–in lots of one or four or eight. One fellow from the Midwest bought all of the MD3s at an average cost of $225; not bad. I got his business card thinking that I might refer MD3-seeking MOR subscribers to him, but he said all those MD3s were already spoken for.

Morrow’s Final Years Spent Preserving Old 78s

George Morrow didn’t waste time moving on to his next idea. Before the final gavel fell on the Morrow Designs’ bankruptcy auction, Morrow announced in early June 1986 that he’d started a new company called Intelligent Access, Inc. This would be a return to Morrow’s roots of sorts, as he planned to focus on designing next-generation disk drive controllers rather than manufacturing computers. Morrow admitted to Newsbytes that his “reluctance to use outside funding” doomed Morrow Designs and he didn’t plan to repeat that mistake this time around.

But Morrow didn’t attract much in the way of venture capital funding. Instead, he sold Intelligent Access to Nestar Systems, Inc., in early 1987. Nestar, which was itself a subsidiary of DSC Communications Corporation, developed local area networks. Nestar effectively purchased Morrow’s disk controller designs and gave him a part-time job as the company’s chief scientist. Morrow told the Oakland Tribune in November 1987 that he only had to work three days a week, and after delivering his contractually required three products, he’d likely “move on” to something else.

There’s not much public information about Morrow’s post-Nestar activities. In 1989, he consulted for Trigem Corporation, a South Korea-based computer manufacturer, to develop a new laptop. He told Wendy Woods that he was also working on a “notepad computer which acts like a piece of paper,” but that he couldn’t find a company capable of actually making it. A few months later, in January 1990, Morrow was part of a group that announced yet another new disk drive controller. The last mention I could find of him in the computer press was at the 1991 COMEX show in Las Vegas, when he told reporters he’d recently recovered from colon surgery.

Morrow spent his later years focusing on his major non-computer hobby–collecting and remastering old records. In 1995, Morrow purchased his own record label, the Old Masters (TOM), to reissue many of the recordings in his collection. Morrow discussed his work with TOM in what was likely his final published interview, with Billboard in June 2001:

[TOM] has released sets by artists as well known as singer Mildred Bailey and saxophonist Frank Trumbauer and as obscure as singer/guitarist Charlie Palloy and banjoist Harry Reser.

For his releases, Morrow draws almost exclusively on his own collection of 70,000 78s, which includes titles from such long-lost labels as the ’30s budget imprint Crown. “They put out a total of something like 500 records, of which something like 450 were dance bands, the rest being strictly vocals,” he says. “Of the 550, I have 375. I probably have a bigger Crown collection than anybody else in the world.”

Morrow has also done important audio restoration work–most recently on Lamento Borincano, an astonishing two-CD set of Puerto Rican recordings issued by Berkeley, Calif.-based Arhoolie Records.

George Morrow died on May 7, 2003, at the age of 69 due to complications from aplastic anemia.

Notes from the Random Access File

- Despite the March 1986 collapse of Morrow Designs, the Morrow Owners’ Review continued to publish until December 1987. There was an interview with George Morrow himself in the final issue. He said he no longer used his own Micro Decision because he needed a MS-DOS machine capable of running dBase II to keep track of his growing record collection, which at that time was just 9,000 78s.

- The Intelligent Machines Journal was yet another early computer publication started by original Computer Chronicles host Jim Warren.

- George Morrow didn’t think much of computer games and video games. I wonder how much of that was due to Judge Miller’s decision in the CBS litigation.

- George Morrow and Steve Jobs did have one thing in common: They liked to design computers without fans. Like the Apple III and the Macintosh, the Micro Decision had no cooling fan. On the other hand, Morrow was firmly against the practice of companies (like Jobs’ Apple) who relied on proprietary batteries. Morrow told PC Magazine in October 1989 that “too many laptop makers have gotten themselves into the battery business.”

- One final quotation from Chairman Morrow: “Portable computers took off because people seem to want handles on their computers–handles that don’t really serve them well. People are attracted to handles.”