Computer Chronicles Revisited 30 — The Data General-One, TI Pro-Lite, HP 110 Portable, and Morrow Pivot

Although Paul Schindler’s commentary comes at the end of the episode just before “Random Access,” I thought I’d discuss his thoughts upfront this time as it helps provide some useful context for this early January 1985 episode, which is about portable computers. Schindler compared a portable computer to a portable sewing machine. With respect to the latter, he said it made more sense for most people just to carry a needle with them. Sure, you wouldn’t be able to do any fancy sewing with a needle, but you could do smaller jobs quickly.

Schindler thought the same was true of portable computers. He eschewed the more fully functional models we’ll see during the main part of the episode in favor of a smaller pocket computer. (A Twitter correspondent suggested the machine Schindler exhibited was a TRS-80 Model 100, which makes sense.) It wouldn’t run CP/M programs, Schindler said, but it didn’t need to. What mattered was that his pocket computer was light, ran on batteries, had a full-size keyboard, and displayed 240 characters on the screen.

More to the point, Schindler said these pocket computers were mostly used by journalists such as himself, and that market was already well served. He therefore didn’t think there was much future for “briefcase computers” like his, but there would be for the larger, sewing machine-type models.

Were Portable PCs Just Another Piece of Luggage?

Indeed, we would see four different “portable computers” on display during this episode. Stewart Cheifet and Gary Kildall actually opened the show by briefly discussing a portable that was even smaller than Paul Schindler’s pocket computer–the Seiko UC-2000, a wristwatch wearable computer that could plug into a separate dock.

Cheifet remarked he wasn’t actually sure you could do anything useful with the Seiko device. And that was his overarching question with respect to portable computers: Was this another case of technology in search of a purpose? Kildall didn’t think so. He said portables were just a new dimension of technology. In the past few years, we’d seen faster processors and more memory in computers. Now what we’re looking for was to get all that speed and power into a smaller package.

This led into Wendy Woods’ first remote segment, which featured some fine B-roll of a businessman–Mike Lynch–traveling through an airport and onto an airplane with his “battery-powered laptop computer.” Woods noted the secret to the success of these “traveling micros” was their ability to record and provide information on the spot and transmit data electronically.

Echoing Paul Schindler’s later commentary, Woods noted that up until now the buyers of portables had mostly been journalists and other people who spent most of their jobs on the road. For example, Lynch put his computer to work collecting up-to-date travel information from around the world and phoning it in regularly to his home computer back in California. Travel agents and airline personnel could then retrieve this information–including weather, currency exchange rates, and special event schedules–by calling Lynch’s home machine.

Woods said that while most portable computers today were far less powerful than the typical home or office machine, they were quickly catching up in terms of both memory capacity and software variety. Portables now came equipped with disk drives and larger screens, and a few could even match the performance of a desk-bound microcomputer. Still, Woods said the future of the traveling portable was not all that clear, as what was considered revolutionary for some might just be “another piece of luggage” for others.

Battle of the Monochrome LCDs

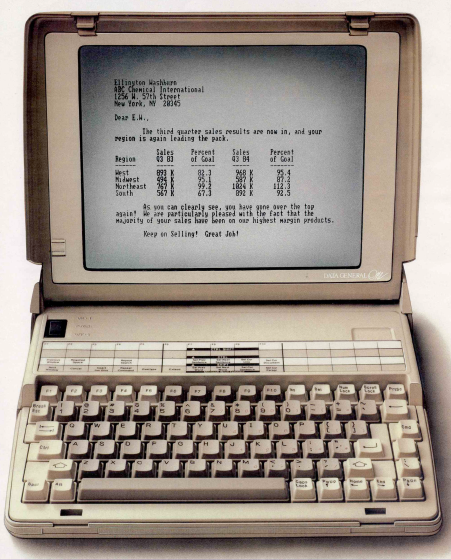

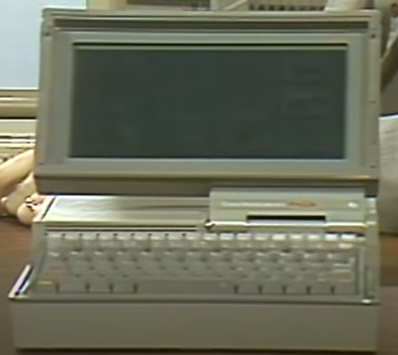

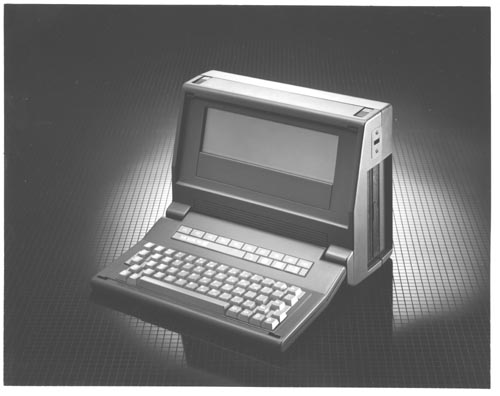

The first studio round table featured Rowland Archer, a manager with Data General, and Faris Gaffney, a product marketing executive with Texas Instruments. The two men were there to demonstrate their companies’ respective portable offerings, the Data General-One and the Texas Instruments Pro-Lite.

Kildall opened by pointing out that what made portables exciting was that a machine this capable 20 years ago would have filled an entire room. Archer said one of the things that made that possible was the use of liquid-crystal displays (LCDs). Archer exhibited the LCD used in the Data General-One, separate from the machine, so he could show off the special video controllers. Kildall asked if this was the same size as a standard cathode-ray tube (CRT) display. Archer said yes, the LCD had a resolution of 80x25 characters or 640x256 pixels for graphics.

Cheifet noted this represented a major advancement. What technology did it actually take to come up with a full-size screen? Archer said Data General approached several Japanese vendors through its Nippon subsidiary. These vendors had just finished producing 16-line LCDs, so Archer said they were not initially interested in starting on 24- or 25-line displays. But Data General was able to convince them of the importance of such displays for the Japanese market. Kildall noted the Japanese were really the pioneers in developing complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) parts, which Archer said made battery-powered portables easier to produce, as they required less power and could be surface mounted on a circuit board.

Kildall asked about the memory capacity of the Data General-One. Archer said the model he brought with him had a base capacity of 128 KB.

Returning to the Data General-One’s display, Cheifet asked about the use of “sub-screens” within the LCD. Archer said that was part of how they solved the problem of creating a full-size display. The screen was divided conceptually into two components run by the display controller. This created a “smooth effect” when scrolling from one end of the screen to the other.

Kildall turned to Gaffney and said that one thing that was notable on all of these portables was that the display was in black-and-white. But a lot of popular applications now required color displays. Did Gaffney see color portables as a possibility anytime soon? Gaffney took this opportunity to show off the TI Pro-Lite, which Texas Instruments introduced in November 1984. Like the Data General-One, the Pro-Lite had a full-screen LCD that displayed 80x25 columns of text. He conceded that color LCDs were not a thing right now but insisted you could still do a lot of work with the black-and-white screens. Gaffney emphasized these machines were targeted at people who primarily worked in the field, such as salesmen, insurance agents, and other sales representatives.

Kildall followed up on that point, asking if people actually used these portables as a primary computing device or merely as a peripheral. Gaffney said there were two uses. The first was as a general productivity aide, i.e., to help field workers be more efficient in entering orders and communicating with their home office. The second use was a new wave of applications that required computer technology to solve a particular problem, such as universal life insurance. This was a very complex field that required a lot of “What if?” analysis, and a portable computer allowed the insurance agent to do this while visiting a client on-site.

Kildall asked if such applications required a larger storage device beyond a floppy disk drive? Gaffney said no, not really. He added there was another new technology in the Pro-Lite–the 256 KB memory chip. That allowed Texas Instruments to put a total of 768 KB of user memory in the machine, meaning there was no sacrifice as far as desktop PC functionality.

Kildall pressed again about the availability of backup storage. Gaffney said the Pro-Lite came with either one or two disk drives. These were newer 3.5-inch microfloppy drives, which had double the storage capacity of 5.25-inch disk drives. Archer noted the Data General-One also used 3.5-inch diskettes, so with two drives the user had 1.5 MB of storage, which was really enough for most applications, particularly considering the number of programs that currently worked with two 5.25-inch drives that had a combined storage of 720 KB.

Cheifet asked about modems and communications, i.e., could these portables be ran as terminals? Were there built-in modems or were those separate accessories? Archer said the Data General-One had a 300 baud internal modem option that fit right inside the unit. It also included a built-in terminal emulator. He noted that many customers used the portable as a terminal with a larger Data General system plus a workstation. Gaffney replied that Texas Instruments took a modular approach, so the modem was a user-installable option.

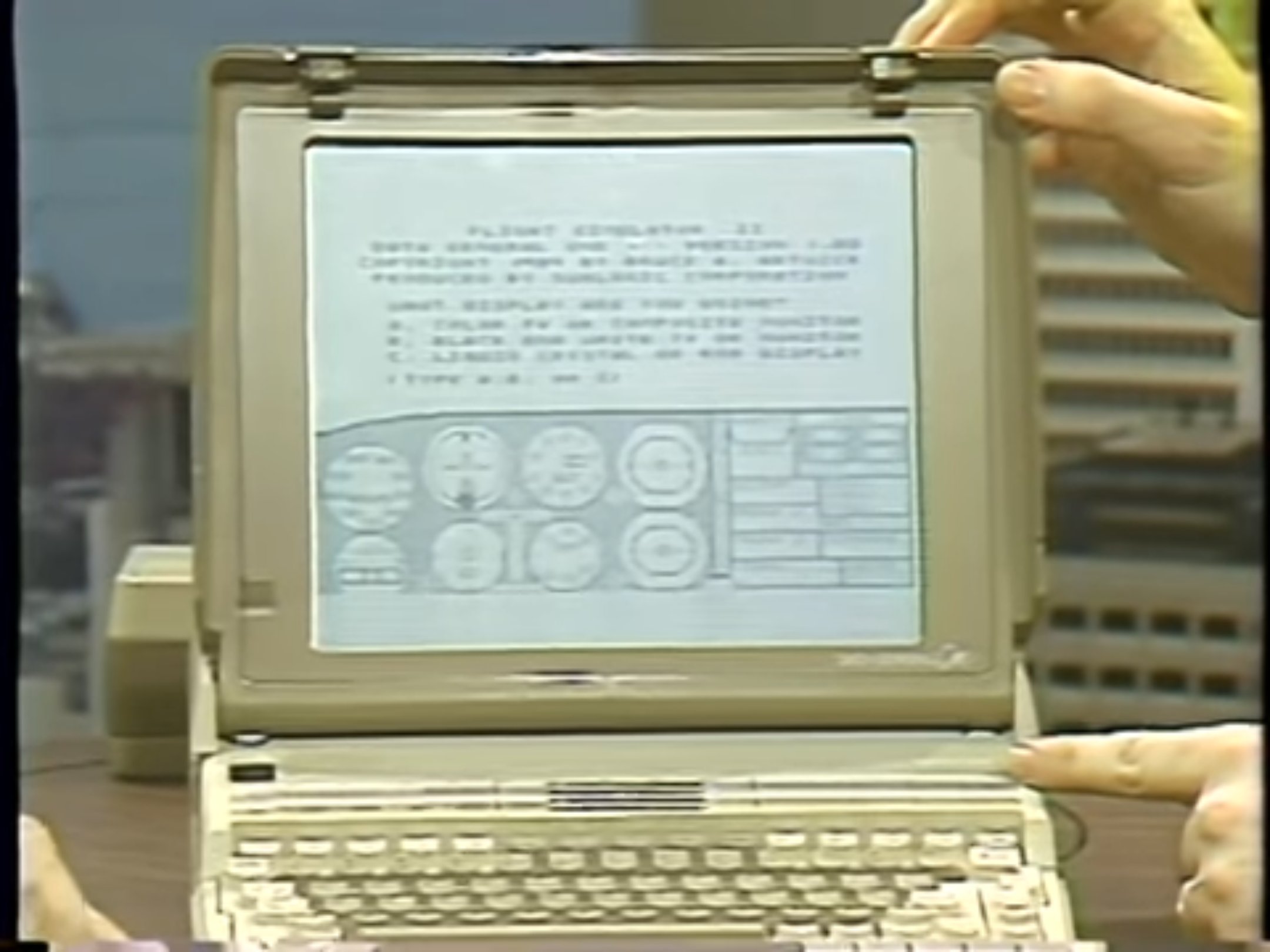

Cheifet wanted to talk about the LCD some more, specifically the fact the Data General-One required 48 KB of its 128 KB of memory just to run the screen. Archer explained that in order to refresh an LCD you needed such a dedicated amount of memory. The 48 KB of screen memory therefore allowed for hi-resolution graphics to emulate IBM PC software, such as Microsoft Flight Simulator, which was displayed on the demo unit.

Kildall added that while these machines might start with 128 KB of memory, the standard today was really 256 KB. Having only one disk drive included also struck him as a limitation. So what about the overall pricing of these machines and their options? Archer replied that there were many third-party software packages that only required 128 KB of memory, so he felt that was a sensible baseline. As for having only one disk drive, the use of double-capacity 3.5-inch drives made up for the lack of a second drive standard. For example, he noted that Lotus 1-2-3–take a drink, everyone!–was now available on a single 3.5-inch diskette. That said, Archer noted that if a customer still wanted more than 128 KB of RAM, Data General was happy to sell it to them.

Kildall asked again about the price range. Archer said the base Data General-One cost $2,895 for 128 KB of RAM and a single 720 KB disk drive. If you wanted 256 KB of RAM and two disk drives, that would cost $4,095. Cheifet asked about the TI Pro-Lite. Gaffney noted the Pro-Lite came standard with 256 KB of RAM and one disk drive for $2,995. The user could also expand the memory up to 768 KB. He added that unlike Data General, Texas Instruments incorporated the screen memory into the LCD drivers. While some users thought this made the LCD slower, he believed the TI drivers made its LCD’s response time comparable to that of a CRT.

The $31 Million Laptop That Never Made It

The final segment began with Wendy Woods’ second remote feature, this time on the decline of Gavilan Computer Corporation, which attempted to market a briefcase-size portable computer that featured a non-standard 3-inch disk drive, an 8-line display, modem, and seven hours of battery life. Woods noted the machine–called the Gavilan SC–made a flashy entrance in the back of a limousine back during the spring of 1983 and, as Woods put it, “appeared to be the machine everyone was waiting for.”

Unfortunately, what Gavilan failed to see was that 3.5-inch diskettes, IBM compatibility, and a 16-line display were becoming standard for portable machines. Gavilan then delayed production of the SC by another year to try and reengineer its machine, which Woods said proved to be a fatal mistake.

Woods interviewed Jan Lewis, a former Gavilan vice president, who described the situation as a “classic case” of having state-of-the-art technology, a really wonderful machine, and what she said was the best sales staff she’d ever seen in the business–but Gavilan missed its window of opportunity. Lewis said the product was simply too late in getting to the market.

Over some B-roll footage of a bankruptcy auction, Woods explained Gavilan filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy at the end of 1984, having only sold about 1,000 of its SC portables. Lewis noted that companies like Gavilan were often leaders in a technical sense, but they failed because they didn’t have enough funding or the market timing was just not quite right. So while Gavilan never made any money, it still contributed greatly towards advancing portable computer technology.

In the end, Woods said that Gavilan burned through $31 million in venture capital funding, making it one of the most expensive failures in the computer hardware market to date.

Color LCD Portables Coming Soon?

Back on set, Gary Kildall said in response to Woods’ report, “A story like that makes me glad I’m in the software business.” He added that the lesson from Gavilan’s failure was that there were a lot of different components that contributed to the success of a small computer system. With portables, he said the display needed to improve considerably, noting that in his own experience while traveling, light coming from different directions often caused the LCD to fade and become unusable.

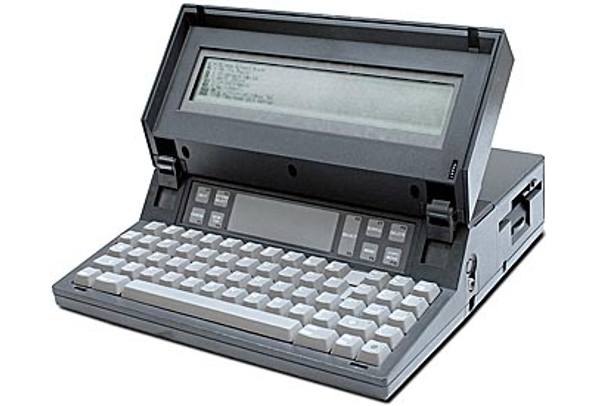

With that preamble, Kildall asked one of our next two guests, George Morrow of Morrow Designs, Inc., to explain how his Morrow Pivot portable dealt with display technology. Morrow explained that LCD technology used existing light to give the user visual information. Another option, electroluminescent displays (ELDs), used their own power to create light much like a CRT. This made ELDs a good option for displays used primarily in environments with low-ambient light. In contrast, LCDs worked better than ELDs in environments with high ambient light.

Cheifet asked how you could cover both of these scenarios. Morrow said the answer, which the Morrow Pivot used, was to backlight an LCD, thus giving it some electroluminescence. He noted these technologies were still in an evolving state. ELDs continued to get more efficient, so in the future they would give more light for less power. As for LCDs, the contrast would continue to improve over time, meaning the user would receive more visual feedback for a given amount of incidental light.

Kildall asked about the work that Japanese manufacturers like Casio had been doing with developing color LCD technology. Could we see that move into computers as well? Morrow said the current focus of Japanese companies was developing flat-panel televisions. Even if they don’t accomplish that, however, he believed that within a year you would start to see portable computers with LCDs that have at least two colors.

Cheifet then asked Morrow for a demonstration of the Pivot and an explanation of how it differed from the previously seen Data General-One and TI Pro-Lite. Morrow said that while the Pivot used an LCD like the other two machines, it had a 5.25-inch floppy disk drive included, as opposed to the 3.5-inch micro-floppy drive. Morrow pointed out that most popular PC applications–such as Lotus 1-2-3–came on 5.25-inch disks. Customers often had to pay an additional fee to get 3.5-inch diskettes.

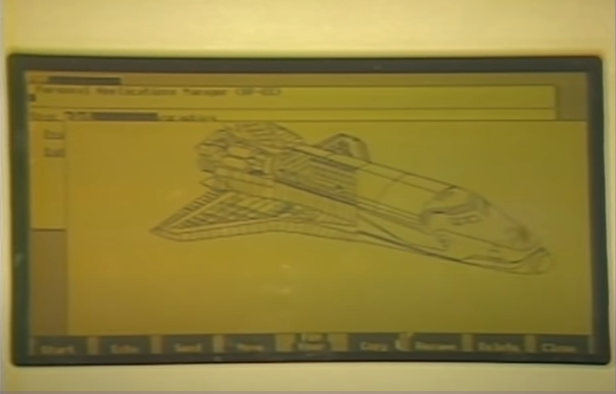

Cheifet interrupted Morrow to ask his other guest, Hewlett-Packard retail marketing manager Srini Nageshwar for a brief demonstration of his company’s product, the HP 110 Portable, which as previously noted utilized an electroluminescent display. The demo showed the HP 110’s ability to produce hi-resolution, albeit monochrome graphics, in this case a detailed drawing of the space shuttle. (Morrow joked you could literally design an airplane in your hotel room with the HP 110.)

Kildall moved onto discussing storage. He noted that while many parts of the portable computers were highly semiconductor-oriented, like the LCDs, the storage still relied on mechanical floppy disk drives. So how did these machines address backup storage? Morrow noted that in the HP 110, the user’s data was kept in static memory. It was a lower-power form of CMOS static RAM that relied on a lead-acid battery. As for the Pivot, Morrow said it relied entirely on floppy disks. It might require more power and make the machine heavier overall, but he felt it provided the best functionality. More to the point, the floppy disk was a standard environment.

Nageshwar said the decision not to include any floppy drive on the HP 110, and instead rely on software built-in to static memory, was that it provided users with “instant availability.” He noted that when was sitting at an airport and looking to get work done on his HP 110, he didn’t want to take time to load a disk. Kildall quipped that perhaps airport terminals were the best place to sell portable computers. Nageshwar agreed, but Morrow decided to be a killjoy, pointing out that he traveled through airports frequently and never saw many portable computers in use.

Cheifet pounced on that and asked about the “real market” for these portables. Nageshwar said the market basically consisted of two groups: People who take work away from their desk and people who normally worked away from their desk. The first group included managers, executives, and professionals. The second group largely included salespeople. Nageshwar said the people in the first group usually needed the ability to run word processors and spreadsheets. They didn’t need a huge suite of programs to run on their portables. As for the second group, they tended to be people who were “really abusing their machines,” so their portables needed to put up with a lot of vibrations. Nageshwar noted the HP 110 Portable had been tested to withstand 100g of force.

Cheifet next asked Morrow to explain the difference between the Pivot and the HP 110 in terms of memory. Morrow replied the Pivot used standard-loss dynamic RAM, which used more power. But later this year Morrow Designs would move towards a CMOS-based RAM that offered a power of reduction by a factor of eight. He said this was probably the best compromise between static and dynamic CMOS memory. The CMOS dynamic RAM didn’t require as much silicon in terms of area on the chip but the amount of power used was virtually the same as for CMOS static RAM.

Kildall moved the conversation to price, noting that Morrow Designs was known for its lower-end prices. What was the price of the Pivot? Morrow said the Pivot started at $1,995, although he believed in the future these type of machines should be priced around $1,000. The $1,995 unit included the Pivot with a single 5.25-inch disk drive and 128 KB of memory. He noted the natural price of a very high-end machine should be around $2,000 and a good utilitarian machine should be around $1,000.

Cheifet then asked Nageshwar about the HP’s pricing. Nageshwar replied that the 110 Portable–which included about $1,000 worth of software built-in to static memory–started at $2,995. He said there was also a model that came with a transportable, floppy-based UNIX system for $4,995.

Utah Company Finds a Way to Make the Mac an IBM Compatible

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which dates the episode in late January 1985.

- A small California company called Novix said it developed a new chip that would allow microcomputers to run at mainframe speeds. The Novix NC 4000 reportedly ran 10 times faster than the Motorola 68000, the fastest 16-bit chip currently available. Novix said its chip had 80 percent fewer components than traditional chips and relied on Forth as its machine language.

- Japan’s NEC announced it had a new process for developing optical discs that relied on organic dyes as opposed to conventional metal dyes. NEC said this meant it could produce laser discs at one-tenth the cost. Cheifet added this could also speed up development of rewritable optical discs for use in computer storage.

- Digital Systems announced a new service called SoftCast that would distribute radio programs to over 1,000 stations across the country, which would include computer data. Cheifet said the plan was to sell software directly over the radio network and provide the first “broadcast-based computer information service.”

- Ziff-Davis announced its new Computer Industry Newsletter, which would be edited by Esther Dyson. The newsletter would be published exclusively over computer terminals, which would receive new issues each evening at 6 p.m.

- Cheifet said there were hints that IBM may be developing a new low-cost replacement for the PCjr. An IBM executive also confirmed the company would start making its own hard disk drives to resolve some of the problems with the IBM PC AT.

- Paul Schindler provided his weekly software review, this time for database manager dBase III from Ashton-Tate. Schindler said he personally used the software to index his own professional articles, but that it was “not for everyone,” as it was complicated and not novice-friendly. It was also expensive at $700.

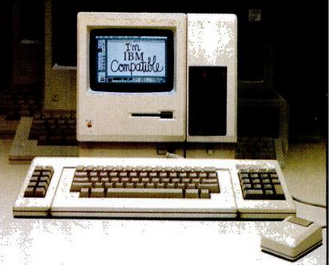

- Utah-based Dayna Communications said it had come up with a solution for people unable to decide between buying an IBM PC or an Apple Macintosh. The company’s new product, the Mac Charlie, allowed Mac users to run PC software while PC users could take advantage of the Apple machine’s mouse, graphics, and user interface. Cheifet said the Mac Charlie would sell for $1,200.

- Koala Technologies announced its latest product, the KoalaCat, a touch-sensitive pad that allowed users to move the screen cursor with their finger.

- Finally, the California Department of Motor Vehicles was in the process of converting to a fully computerized system. Cheifet said the DMV currently had a backlog of 87,000 transactions, which was growing by 20,000 additional transactions each month. This left thousands of residents stuck with expired registrations and licenses. The DMV admitted it “grossly underestimated” the problems of converting to computers. The agency was now asking for $5 million to hire new people and pay for overtime so that “humans [could] clean up the mess.”

Morrow Designs Undone By Massive Debt

Two of the four companies that demonstrated portable computers in this episode, Data General and Morrow Designs, are no longer in existence. Data General, founded in 1968, originally made a name for itself selling the NOVA minicomputer, which “quickly became a popular machine in scientific and educational markets,” according to the Computer History Museum. By the mid-1980s, Data General’s fortunes had started to slump as microcomputers were becoming more popular. The Data General-One represented the company’s attempt to make inroads in the consumer market. It apparently didn’t take. Towards the end of the decade, Data General pivoted to producing UNIX-based machines. In the 1990s, the company moved away from computers altogether and decided to focus on storage devices, culminating in its 1999 acquisition by EMC Corporation.

As for Morrow Designs, its decade-long run as a small computer manufacturer abruptly came to an end in March 1986 when the company filed for bankruptcy. According to Nancy Groth of InfoWorld, Morrow Designs had run up $5 million in debt and reported a $7 million operating loss. And while the company had recently licensed its final portable computer design, the Pivot XT, to Zenith Data Systems to fulfill an order for 15,000 computers from the Internal Revenue Service, Morrow Designs would receive no royalties from that deal, just a flat fee of $1 million. George Morrow himself told Groth that the Zenith deal was just one reason for the company’s demise. Morrow also cited an overall downturn in the computer industry and the simple fact “the company borrowed too much money.”

Ironically, George Morrow is probably better remembered today for his affiliation with Computer Chronicles than with his eponymous computer company. This episode marked the first of Morrow’s many appearances on the program during the rest of the 1980s and early 1990s. He will serve as substitute co-host in Gary Kildall’s absence and later provide some of the end-of-episode commentaries.

Archer, Nageshwar Had Long Careers in Tech

Rowland Archer spent nearly 25 years at Data General, remaining with the company until 1992. In 1995, he joined HAHT Commerce as its chief executive. Global Exchange Services later acquired HAHT, and Archer remained with that company–later renamed GXS–as a senior vice president and chief technology officer. Archer moved to ReadSoft, a Swedish company that developed specialized business application software, in 2010 to oversee its U.S. subsidiary, which focused on integration with Oracle-based systems. He remained with ReadSoft until 2015.

Like Archer, Srini Nageshwar also had a quarter-century run at a legacy tech company, in his case Hewlett-Packard. Nageshwar was with HP from 1964 until 1989. In 1991, he became chief executive of the European branch of Iomega, the company best known for manufacturing the Zip drive. After retiring from Iomega in 1998, Nageshwar joined the board of directors of TVS Electronics Ltd., an India-based company, where he also chaired the audit committee until 2008. Since 2001, Nageshwar has been the chief executive of DyAnsys, an India-based manufacturer of medical diagnostic tools that assist patients with chronic pain management.

I don’t have much to report regarding our other in-studio guest, Faris Gaffney, formerly of Texas Instruments. I found sporadic references online to his employment with Scientific-Atlanta and Interstate Electronics Corporation, both companies that apparently specialized in telecommunications equipment, with Gaffney joining the latter in 1996.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of January 22, 1985.

- The Seiko UC-2000 featured by Stewart Cheifet during the introduction wasn’t exactly a smartwatch in the modern sense. Riccardo Bianchini described it in a recent article as a “programmable calculator” that could be paired with a dock station, which included a " small thermal printer, a keyboard, 4 KB of RAM, and a 26 KB ROM which included a Microsoft Basic programming software, a Japanese / English translator, and some games."

- In a December 1998 essay for Inc., Gavilan Computer Corporation co-founder and CEO Manuel Fernandez said his major mistake was that he “stopped at $30 million” in venture capital funding and turned down an opportunity to raise another $60 million because “my cofounders and I were intent on trying to hold on to the equity of the company.” As a result, Gavilan simply ran out of cash before it could get its Gavilan SC laptop to market.

- Much like George Morrow, another person featured in this episode, former Gavilan executive Jan Lewis, will become a regular guest on Computer Chronicles going forward.

- The Novix chip didn’t just use Forth as its machine language. Novix was actually co-founded by Chuck Moore, the creator of Forth.

- The Ziff-Davis Computer Industry Daily did not last long. The publisher pulled the plug after just three months. According to the New York Times, potential readers “greeted the $1,000-a-year paper with all the enthusiasm of consumers eyeing the 40th I.B.M.-compatible personal computer.” Esther Dyson went back to publishing her own industry newsletter, Release 1.0, which she originally started in 1983 and continued to write until 2006.

- While it sounded ridiculous to me, the Mac Charlie was a real thing. InfoWorld described the product as “a box that surrounds the Mac and contains an Intel 8088 coprocessor, a self-contained 5.25-inch disk drive, and several additional ports.”

- It’s been 36 years, but I bet the California DMV still hasn’t gotten through that backlog.