Computer Chronicles Revisited 42 — David Crockett, Sam Colella, Deborah Wise, and David Norman

The third season of Computer Chronicles debuted in September 1985 with a two-part look at the “slowdown in Silicon Valley.” Basically, these next two episodes consisted of round tables with people representing different facets of the computer industry to discuss why things seemed to be going much worse in 1985 as opposed to 1984. This first episode focused on the perspectives from venture capital, the media, analysts, and retailers, while in the next episode we’ll hear from software and hardware manufacturers.

“Orphaned” Computers Highlighted Industry Downturn

Stewart Cheifet did his cold open standing outside a “shiny new building” in Silicon Valley–specifically, the Kifer Tech Center in Sunnyvale–which he said was supposed be the home of several new hi-tech startups. But the building was now vacant and the one next to it was unfinished and abandoned for the moment. Cheifet rhetorically asked what caused “the crash in computers” and would it last?

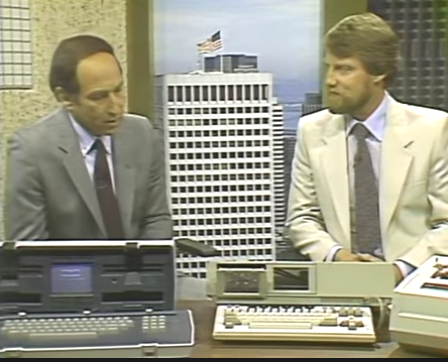

In the studio, Cheifet and Gary Kildall sat at their customary table. In front of them were two personal computers, an Osborne 1 and a Coleco Adam, which Cheifet said were now “orphans” in the computer industry. They were highly praised when they first came out for their new technology but were now no longer in production. Cheifet noted that all one seemed to hear these days about the computer industry was stories of disaster and failure. Cheifet asked Kildall for his perspective as someone who had started two tech companies, first Digital Research and now Activenture (later renamed KnowledgeSet).

Kildall said there were a lot of components to the computer industry. For example, there were chip manufacturers like Intel, who were being hit hard by Japanese competitors on price. Commercial hardware systems, such as the Osborne, were in a market now dominated by IBM. In the home market, companies like Coleco never really established what people could do with a computer besides play games. As for the software industry, there had been growth, but that also meant growth in the number of suppliers, which had led to price erosion. Ultimately, Kildall said the way the industry would get out of this slump was by continuing to pursue innovation and new technology.

PC Industry Growth Slowed from 76 Percent in 1983 to an Estimated 4 Percent in 1985

Marking her triumphant return to Chronicles, Wendy Woods provided some B-roll narration setting the stage for this episode’s theme. She said Silicon Valley’s brief-but-tumultuous history was marked by unlimited optimism and brilliant innovations that brought companies sudden success–and frequent failure. And if continuing growth had cushioned Silicon Valley from America’s economic problems, the recent news was not so good.

In 1983, Woods said, worldwide sales of personal computers increased 76 percent. But in 1984 the increase was only 19 percent. And for 1985, analysts predicted growth would slow to about 4 percent. Losses among the two largest home computer makers through June 1985 surpassed $600 million. (I think Woods is referring to Commodore and Apple, but I can’t be certain.)

Woods said repercussions in related industries were equally severe. Canceled chip orders had created a backlog for semiconductor manufacturers, where sales had dropped 25 percent in the past year. And the number of U.S.-based computer makers declined from over 150 to about 40, with a similar drop among software producers.

While poor sales led to curtailed predictions and a bleak outlook, Woods said the reasons for the slump were not clear. The more expensive group of PCs aimed at the business market grew by 25 percent in 1984 while sales of machines under $1,000 showed no increase. At worst, Woods said, the industry’s new self-doubt was based on uncertainty about who was using the product (and for what).

As Number of PC Manufacturers Shrank, Focus Turned to Applications

This episode was all about the round tables. The first group had E. David Crockett and Sam Colella join Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Kildall opened by asking Crockett, the president and CEO of market research firm Dataquest, about where the slowdown was actually occurring within the industry. Crockett said “slowdown” was something of a misnomer compared to what the industry had accomplished in the past 10 years. He noted that the personal computer industry was worth $26.3 billion and had grown 80 percent in 1984. He saw 1985 as more of a consolidation or pause before further expansion, but even now there were certain segments that continued to do well in 1985, such as business computers and higher-end PCs.

Kildall compared the situation to building a crest on a wave, and then when the crest broke it was a question of what to do with the extra resources. Crockett agreed, stating there was an over-capacity problem. At one point there were over 375 manufacturers and once demand caught up with supply, there was an adjustment period.

Cheifet interjected at this point, asking if this was a case where bad forecasting or bad management by the manufacturers caused them to become overloaded with inventory. Crockett said he didn’t think so; rather, it was more due to the fact that no industry had ever grown at this phenomenal rate. He noted that the computer industry had grown at rates greater than what DataQuest’s own predictions had thought possible. And that phenomenal growth rate “invited” a lot of people into the industry before the supply chain could catch up. For example, he said there was now 40-percent overcapacity in semiconductors, which forced some chipmakers to reduce prices as much as 85 percent since January 1985. Such price reductions in turn spurred demand for PCs as manufacturers could now offer better price-performance on their machines.

Kildall asked about the effect of IBM’s dominance on the PC industry. How did that affect any industry slowdown? Crockett said it certainly played a role in the sense that IBM established its channels and reached a certain level before setting lower goals this past year. IBM had publicly announced in 1984 that it planned to triple its supply of computers, which Crockett said it did. But this year, IBM said it only expected a 20-percent increase, which Crockett said it would also likely meet.

Kildall then turned to Colella, a venture capitalist with Institutional Venture Partners, and asked for his views of the situation, noting that venture capital had started to dry up. Colella said there was an excess of investment. He said there were 375 companies in the business at one point was due to “great expectations.” Basically, anyone who could build a microcomputer got into the business. Anyone who offered a concept for the “next, better computer” could get funding. As a result, too many deals were funded in a rush to the market. And most of those startup firms ran headfirst into IBM. Colella said IBM had the most impact on those fledgling companies. Today, the venture capital community now saw itself as over-invested and not very interested in new personal computer deals.

Kildall asked Colella what he looked for now with a small company in terms of growth. Collela said they looked for the same things they always looked for–a well-thought-out plan, a management team that understood the market, and an exciting new market niche. The key was really finding new markets that existing large companies were not paying attention to and establishing a beachhead there. Kildall observed the previous approach would have been to invest in a very broad-based market but now venture capital was looking towards narrower, vertical markets, such as medicine or law. Colella agreed. He added that it was now more about the application of the computer rather than the personal computer itself. People were looking for higher utility in their hardware. They wanted greater productivity that would help improve the bottom line for their businesses. These customers needed more “intellectual” help, and Colella said the venture-capital community was more interested in that area.

Cheifet asked Colella for more specifics–what kinds of applications? Colella said one example would be CD-ROM, in particular databases that were now only available online or distributed via paper. (Colella slyly acknowledged Kildall, whose Activenture focused on this area.) New optical technology made it possible to put those databases on a disk and use the PCs that people currently owned to perform data manipulation and database handling.

Kildall pivoted the discussion to the home market. Crockett said that in 1984, about 9 percent of U.S. households owned a personal computer. In 1985 it was up to 13 percent. But the growth tended to be more at the higher end of the market, i.e. systems priced above $500. And most people who owned home computers were using them for business and professional work. To become a true home market, Crockett said, would require more of the types of niche applications that Colella mentioned, such as a localized database that enabled transactions over the telephone. Kildall said this meant the right home application hadn’t been found yet. Crockett said that was correct.

Cheifet asked if the current situation would be healthy in the long run–i.e., while it may hurt a little bit right now, we would end up with better-managed companies and a more fine-tuned industry. Crockett said he thought that would turn out to be true. He noted that it wasn’t just personal computers; there were also probably three or four too many players in the peripherals markets, such as printers. The companies that managed to survive would have lower-cost manufacturing and better methods of distribution. So it would be healthy in the long run for the computer industry, just as it was previously in other markets such as automobiles.

Cheifet closed the segment by asking Colella when he thought when and how things would turn around in the computer industry. Colella replied the market was currently plateauing and that the latter half of 1985 and 1986 would be much stronger. We wouldn’t see the dramatic 80-percent growth of previous years, but there would be an emergence of new applications and new peripherals that would make computers easier-to-use in both the home and business markets.

Business PC Sales Remained Strong Despite Home Market’s Struggles

For the second round table, Deborah Wise and David Norman joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Kildall opened by asking Wise, a journalist with Businessweek, if all this talk about a “slowdown” was just media hype or was it really taking place. Wise said it wasn’t hype. There were a number of firms currently losing money. For example, Apple Computer–once the “darling” of the personal computer industry–had recently shut down several factories and laid off thousands of workers. And IBM was holding on to an unknown number of machines in its inventory.

Kildall followed up, asking Wise for her views on what caused the slowdown. Wise replied that it was oversupply. Companies had ramped up production expecting 80-percent growth rates to continue and now they had to slow it down.

Kildall then turned to Norman, the president of computer retailer Businessland (and the founder and former CEO of DataQuest), and asked if he saw the effects of this over-supply at the retail level. Norman quipped that he “wondered if he was in the same business,” because Businessland’s sales were up almost 200 percent in the first half of 1985 compared to the same period in 1984. Nevertheless, he conceded that the growth rate of the computer industry as a whole had slowed. But the business computer market was still growing by about 30 to 40 percent in 1985. Norman attributed that continuing growth to the dominance of IBM, which he estimated had about 70 percent of the market for business PCs (i.e., computers priced at $1,500 or greater).Kildall observed that the slowdown among suppliers and the growth of retail channels led to a situation where more and more suppliers were fighting to get shelf space. Norman agreed with that assessment.

Kildall asked if there was a noticeable “price erosion” taking place, meaning that even as the number of computers being sold continued to grow, the total value of the industry was somehow stagnant. Norman pushed back a little on this, stating he believed there was currently a 30 to 40 percent growth in “revenue dollars” in the business segment (as opposed to the home market).

Wise interjected, noting that even in the business PC market there had been a “squeezing of margins.” A growing number of “gray market” PCs had forced retailers to cut prices on IBM machines. (I assume she’s using “gray market” here to mean IBM PC compatibles.) She added that while Businessland may be doing fine, other retailers were really hurting. Norman agreed there were a number of competitive price pressures in the market, but on the other hand Businessland’s margins were moving up. He said the average Businessland system sold for about $6,000, up from $5,000 just two years earlier. So even though semiconductor prices were coming down about 20 to 25 percent annually, the business professional continued to pay a premium for more memory, faster printers, and so forth.

Kildall tried to steer the conversation back to the home computer market. Norman said Businessland had never really been in the home market, and he personally had trouble understanding it. He said at this point, he didn’t see the value in buying a computer for the home. Wise agreed the applications weren’t there currently for the home market. But she said there was still increasing “hype” from home computer vendors, such as Atari and Commodore, trying to get things going for the upcoming Christmas season.

Drawing on his own experience as a software developer, Kildall asked about the effects or price erosion on software. He said that by distributing software through standard retail channels–where the distributor and the seller each takes their cut–the money just wasn’t there to develop software. Didn’t that also have a dampening effect on the entire industry? Norman agreed this was a problem for lower-priced software, which still required a significant amount of training and support at the retail level. However, just as with hardware, Businessland had seen success at the higher end of the market. For example, Businessland sold a computer-aided design (CAD) software package for $2,500. They weren’t focused on the $50 software packages.

Cheifet asked Norman to comment on the reports of recent struggles at another well-known computer retailer, Computerland, which was dealing with layoffs and potential bankruptcy. Why did Norman think they were having problems? Norman reiterated it came down to the differences between the business and home markets. Computerland focused on the latter, which was a “very soft” and “almost non-existent” market at the moment. Norman said it came down to companies doing their market research. He saw tremendous opportunities in emerging areas like integrated voice-data workstations and business software. But having 375 companies building the same basic IBM AT was not going to make for a successful company.

Looking ahead, Kildall asked Wise what would lead the industry to “take off” again. Wise said the next round of new promotions for the Christmas season would help spur the market. But it would still come down to new applications that made the machines more interesting.

Cheifet pressed Wise on the home market. Would people actually buy new home computers like the Amiga 1000 and the Atari 520ST? Wise said yes, although she didn’t expect massive growth. In the long run there would be new applications to draw in that 87 percent of households that didn’t currently own a computer. She added, however, that finding retailers to sell these machines would be a problem. Computerland was having a hard time finding a market for itself. A number of other stores were also dealing with bankruptcy as the result of reduced margins.

IBM and Microsoft Continued to Develop PC-DOS Standard

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which is dated in September 1985.

- IBM and Microsoft announced a new long-term development deal to keep PC-DOS (i.e., MS-DOS) on the IBM PC line. Cheifet said the new deal meant that IBM would not move to a new proprietary operating system. That in turn should help “stabilize” the PC market as software developers could continue to rely on IBM’s commitment to the current open hardware standard.

- Cheifet said there were now several online mortgage database services that could quote show the best rates in a given area, calculate a borrower’s monthly payments, and even advise a buyer how big a mortgage they could handle on their income. Cheifet said the three biggest online mortgage services were CompuFund, Loan Express, and ShelterNet.

- Seventeen new computer magazines were launched in the past eight months, Cheifet said, adding that advertising revenues were down at 9 of the 10 current leading computer magazines.

- Despite the slowdown in Silicon Valley, a number of foreign countries continued their efforts to lure tech companies from northern California. Cheifet said delegations from Austria, West German, the Netherlands, Thailand, and Switzerland had recently visited Silicon Valley. But the most successful efforts were from Scotland and Ireland, with about 300 U.S.-based hi-tech firms now located in those two countries.

- Paul Schindler reviewed CataList (Automation Consultants International, $250), a mailing list manager that integrated with over a dozen popular word processing packages to create form letters. Schindler said the program was “truly impressive” and had “the fastest sort I’ve ever seen.”

- The Computer Arts Institute planned to open the first computer artist program in Corte Madera, California, in the fall of 1985.

- The computer system that ran the automated-teller system for Mellon Bank in Pittsburgh failed, meaning the machine couldn’t recognize any customer account numbers. This meant during a 90-minute period, the machines started “eating” customer ATM cards–about 2,000 in total.

- A worker at a struggling Intel chip fabrication plant in Albuquerque, New Mexico, put up a Hopi kachina doll in response to low production yields. “Call it what you will,” Cheifet said, but Intel now reported the New Mexico plant was its most efficient.

All Roads Lead to Venture Capital (or Politics)

Since this was a people-focused episode without any product demos, I’ll briefly run down each of our four guests and what became of them:

- Earl David Crockett earned his master’s in electrical engineering and computer science at Stanford University before completing a doctorate at the University of Illinois. He worked for IBM, where he helped developed early modems and CRT displays, before moving to Hewlett-Packard for nine years. He then spent four years at DataQuest, including two as president and CEO. Not long after his Chronicles appearance, Crockett founded Pyramid Technology Corporation, which manufactured minicomputers, and served as its president and CEO. By 1988, Crockett jumped to the venture capital world, fist with 3i Ventures and later as a founding partner with Aspen Ventures

- Samuel Colella was still relatively new to the venture capital world when he appeared on Chronicles, having started with International Venture Partners in 1984. In 1999, he co-founded Versant Ventures, a venture capital firm that focuses on the health care industry, where he remains managing director.

- As mentioned in the episode, David A. Norman actually founded DataQuest and served as its chairman and president until he resigned in March 1982 to start Businessland. While Businessland may have been doing great in the fall of 1985, things started to go bad when Norman signed a distribution deal with Steve Jobs in 1989 to carry the latter’s NeXT computers. As Luke Dormhel noted in a May 2021 retrospective for the Cult of Mac, “By the end of the decade, Businessland had sold just 360 [NeXT] units. Even worse, Businessland spent $10,000 for every NeXT Computer sold, due to forced investment in a dedicated sales and marketing team.” In 1992, Businessland closed for good.

- Deborah Wise grew up in the United Kingdom before studying journalism in the United States. She spent nine years covering Silicon Valley for Business Week and other publications before moving to Paris to ghostwrite the autobiography of a well-known French flutist. In the 2010s, Unger worked for Transparency International, an anti-corruption nonprofit organization. In 2017, she ran as the Liberal Democratic Party’s candidate in the United Kingdom general election, losing to former Conservative Party leader and cabinet minister Iain Duncan Smith.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of September 3, 1985.

- New season, new sponsor: The now-defunct American Federation of Information Processing Societies (AFIPS) was now a presenting sponsor of Computer Chronicles, together with computer magazine publisher McGraw Hill, which continued its sponsorship from the previous season.

- The Kifer Tech Center did not remain empty for long. Indeed, it is still up and running today, and at last report fully leased.

- I previously discussed the Osborne 1 in a prior episode featuring Adam Osborne himself. As for the Coleco Adam, it was a disastrous attempt by Coleco Industries, Inc., to expand its ColecoVision video game console into a full-fledged computer. The Adam notably came bundled with a daisy-wheel printer, which was actually required to power the computer. The 1984 crash of the video game console market, coupled with the 1985 slowdown in home computer sales, dealt a mortal wound to Coleco. The company, which started out in leather supplies before moving into toys and then electronics, managed to stumble along a few more years behind the success of its line of Cabbage Patch Kids dolls before finally succumbing to bankruptcy in 1988. Most of Coleco’s assets were sold to rival toy company Hasbro in June 1989.

- It’s worth noting that all three of the main U.S. companies brought down in the video game crash–the original Atari, Coleco, and Mattel–all tried to simultaneously enter the low-cost home computer market. Only Atari’s 8-bit line enjoyed any success. And the looming introduction of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in October 1985 would only further exacerbate the home computer industry’s struggles.

- David Crockett’s successor as president of DataQuest was Manny Fernandez, the former president of Gavilan Computer Corporation, which was featured in a prior Chronicles episode on portable computers. Fernandez, in turn, left DataQuest in 1991 to become president and chief operating officer of Gartner Group, Inc. Fernandez later served as Gartner’s chairman and in that role helped Gartner acquire DataQuest in a 1995 deal. Gartner remains in business today.

- As important as the new DOS deal was for Microsoft in the long run, it’s interesting to note that in 1985, sales of MS-DOS only accounted for about 20 percent of Microsoft’s revenues–at least that’s what Bill Gates told the New York Times.

- For some reason, there was an Apple II sitting on the desk during the second round table, even though it was never turned on or used on-air.