Computer Chronicles Revisited 41 — MacDraw, Dazzle Draw, the Magic Video Digitizer, and Lumena

When Computer Chronicles first delved into the topic of computer graphics back in April 1984, the focus was largely on high-end professional systems, such as the $150,000 Quantel Paintbox. More than a year later, in June 1985, Chronicles closed out its second season with another computer graphics show that looked at more affordable offerings for personal computer users.

Would Artists Abandon Paintbrushes for Graphics Pads?

Stewart Cheifet did his cold open at a California museum standing in front of what he described as “a fine example of abstract expressionist art” by artist Dan Cooper that was made using an Apple II. Cheifet quipped that old artists’ tools like brushes were becoming “passe” and replaced by touch-sensitive graphics pads and sophisticated graphics software.

In the studio, George Morrow of Morrow Designs joined Cheifet as co-host for this episode. Cheifet showed Morrow an Etch-a-Sketch toy, which Cheifet joked was the closest he ever got to “computer graphics” as a kid. Cheifet noted that a year or two earlier, people were merely talking about computer graphics, but now there was an explosion in the sales of graphics software. Why the change? Morrow replied there had been dramatic changes in the available hardware and software. The best example, he said, was the Macintosh, which made it much easier to create visual images without all the work that used to be required. And we were now seeing the same effect starting to move over into the IBM PC and compatibles world. Morrow thought this would change the way commercial artists worked over the next year or two.

Creating Physical Book Covers Digitally

Marking her final Chronicles episode, Robin Garthwait presented the first of two remote segments, this one profiling how a graphic artist, Inga Infante, used a computer in her work as a book cover illustrator. Garthwait noted the graphic artist ran her business based on creativity–turning ideas and concepts into visible form. Before computers, the tools for this transformation were based on ink, paint, or dye. Putting the line to a piece of paper meant committing the idea to a form.

Today, Garthwait continued, the computer’s special ability to manipulate ideas gave the artist a new electronic flexibility. While artists like Infante still kept traditional tools in her studio, Garthwait said she had moved most of her art to the computer screen. The original design is drawn on a digitizing pad. Colors are then applied from a choice of palettes displayed in a corner on the screen. Infante no longer needs to make numerous copies of her design when submitting them for approval, Garthwait said, as now she could draw several copies on the screen and make transparencies of each. If the publisher wanted changes, Infante could recall the design from disk and make the change without affecting the rest of the artwork.

Garthwait noted that graphics packages were now available for a wide range of computers ranging from the Commodore VIC-20 to the newest supercomputers. But a sophisticated application didn’t always mean a sophisticated price. For instance, Infante did her cover design work on a Zilog Z80-based computer with some external graphics support.

Perhaps the biggest advantage of computer design, Garthwait said, was the amount of time it saved. She noted Infante’s book cover for Dale Peterson’s CoCo LOGO for the TRS-80 Color Computer would have taken four times as long to design by hand as by computer.

Utilizing the Graphics Capabilities of the Macintosh

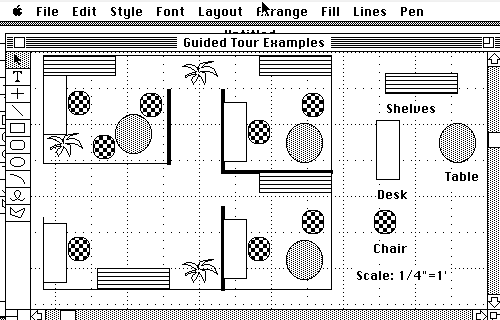

Marein Cremer and Mark Bulla joined Cheifet and Morrow for the first round table segment. Cremer, a product manager at Apple Computer, was there to demonstrate MacDraw, a vector graphics package for the Macintosh. Morrow asked Cremer how MacDraw differed from MacPaint. Cremer said the basic difference was that MacDraw had a “structured approach,” which meant that each object was regarded as a separate entity, and once it was on screen it could be manipulated at any time. That made MacDraw attractive in the business environment for use in presentations. MacDraw was also useful in the technical area due to its ability to make precise, accurate drawings for things like architectural and engineering design.

Cheifet asked for a demonstration. Cremer used MacDraw to make a simple business organizational chart. She also showed how you could manipulate a sample office floor plan, which I’ve reproduced below using emulation of the original MacDraw software.

Cheifet then turned to Bulla, the director of technical services with New Image Tech, Inc., to demonstrate his company’s product, the Magic image digitizer. Bulla explained that Magic took a video signal, cut it up into little pieces, assigned gray patterns to the levels of light, and placed a digitized image into a MacPaint file. Morrow asked about the practical use for such digitized images. Bulla said one use case would be placing pictures into a small company’s newsletter.

Bulla demonstrated Magic by taking and digitizing an image of Morrow using what was basically a security camera attached to a Macintosh.

Morrow asked how much the system cost. Bulla said the digitizer itself, including the software and hardware, sold for $349. The camera was an inexpensive security camera that cost an additional $149. Morrow seemed impressed by the overall low cost–$500 for a digital imaging system–and said Bulla’s company would have trouble keeping up with demand come Christmas. Bulla then showed some additional sample images from the Magic software, which displayed up to 38 levels of gray. Morrow remarked that as memory became cheaper, computers could store more complex images like these samples.

Cheifet asked if it was possible to manipulate images taken with the Magic system in the same way as objects used in MacDraw. Bulla said sure, you could manipulate Magic images in either MacPaint or MacDraw. Cheifet asked if it was possible to make a hard copy. Bulla said yes, you could print images out using a Hewlett-Packard or Apple laser printer.

Cheifet asked about the other practical uses of the Magic system, i.e., what would users really buy it for. Bulla replied there were a number of possible scientific applications, such as X-rays, that could make use of the software’s ability to assign different patterns to different light intensities.

Mac-Like Capabilities on the Apple II

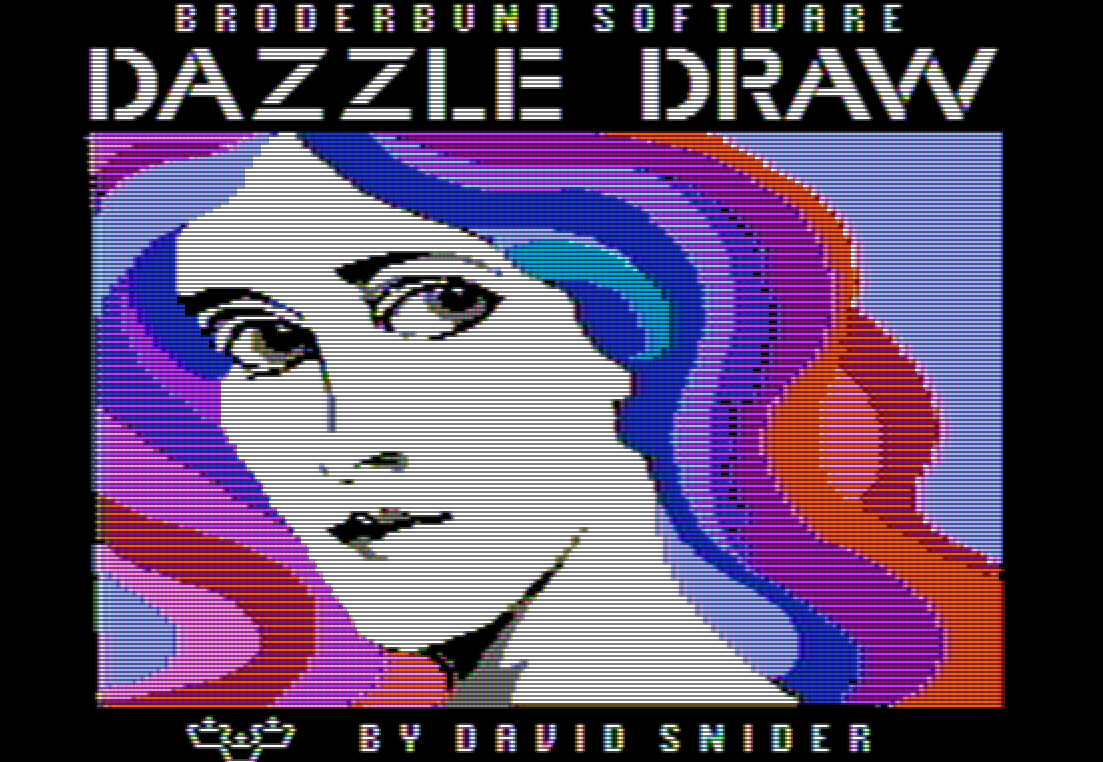

The second studio round table had Ed Bernstein and James Dowlen join Cheifet and Morrow. Bernstein was the director of product development for Brøderbund Software, which published Dazzle Draw, a graphics package for the Apple II computer line. Brøderbund was also known for publishing computer games. Morrow asked what influence the game software had on Dazzle Draw. Bernstein replied “quite a lot,” noting that high-resolution screen graphics went hand-in-hand with the development of games. Bernstein noted that Dazzle Draw was designed by David Snider, himself a former game programmer.

Beginning his demo, Bernstein explained that Dazzle Draw did what MacPaint did except in 16 colors and on an Apple II, which cost much less than the Macintosh. Bernstein showed off a sample image of a butterfly that was included with the software.

Morrow noted the Dazzle Draw interface was reminiscent of the menu-driven system used on MacPaint. Cheifet concurred, noting Bernstein was also using a mouse, similar to a Mac. Bernstein said Brøderbund made “no bones about” the fact they set out to make essentially a Mac-like for the Apple II.

Cheifet asked about the memory requirements for Dazzle Draw. Bernstein said it required 128 KB of memory. The Apple IIc came standard with that amount, but if you used a IIe it would require a 128 KB memory expansion card.

Cheifet noted there had been earlier drawing programs for the Apple II machines. What was the difference between Dazzle Draw and those earlier applications? Bernsten said there were two key differences. First, the expanded memory in the IIc and expanded IIe now made it possible to do “double high-resolution” graphics. Previously, the Apple II could only produce high-resolution graphics in four colors. Now you could get high resolution with more color choices. The second big difference was that Dazzle Draw used a Macintosh-style user interface, which made it easier for the user to manipulate menus and objects.

Cheifet then turned to Dowlen, an artist with Time Arts, Inc., and asked for his reaction to software like Dazzle Draw. Dowlen said he was impressed by the number of colors and high resolution available, as well as the speed at which images could be created on the computer. He said this opened up a whole new world for artists such as himself. Cheifet followed up, asking if it made him feel good or bad to use a computer versus traditional paint and brushes. Dowlen said some artists might be intimidated at first because they might think they need to know programming. But the computer was just a new medium, similar to when photography first came around.

Bringing a “Cinematic” Approach to Computer Animation

Robin Garthwait presented her second and final remote segment, which featured the work of Pacific Digital Images (PDI), a California-based company that produced animated computer graphics for the television industry. Garthwait interviewed PDI’s founder and president, Carl Rosendahl, who explained that animation and software development were similar. The tools used to develop software were in many cases applicable to also developing animation. You took a 3D model in a 3D space with a “camera” and “lights” that existed only as databases inside the computer. When that was all set up, you could then tell the computer to show you what a scene would look like through the virtual camera.

Garthwait noted that as the tools of the trade became more sophisticated, the designs became more subtle and complex. Rosendahl said that there was now more editing of shots in computer animation projects. He cited PDI’s recent work on the introduction to Super Bowl XIX for ABC, a 30-second piece that featured 10 different shots and was one of the first times the company had designed a piece with a “cinematic” approach. Rosendahl said that everyone at PDI had a rare cross between the arts and computer science. Most PDI employees had a technical degree as well as some background in the arts, such as film making, animation, sculpture, or photography.

Lumena Provided 3D-Like Power for a Price

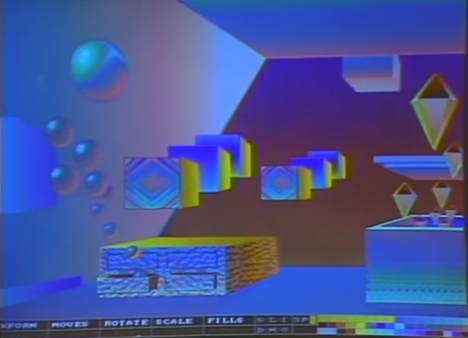

Back in the studio, James Dowlen demonstrated his company’s product, Lumena. Cheifet asked what Lumena did that something like Dazzle Draw did not. Dowlen said with Lumena, the artist had access to an on-screen palette of 256 colors at any one time–out of a complete choice of about 16 million colors. And while his demo was set up to display a resolution of 512 pixels across, Dowlen said Lumena could create images of up to 2,024 pixels across. (For comparison’s sake, the double-high resolution on the Apple IIc was 560 pixels across and the system had a total palette of 16 colors.) Morrow noted that 2,000 pixels-per-inch resolution was comparable to what could be achieved with 35mm color film.

Cheifet asked Dowlen about the hardware configuration used to run Lumena. Dowlen said there was an RGB monitor and a PC-type computer with a hard drive. Morrow said most of the expense was likely for the color monitor.

Dowlen then demonstrated the Lumena software, showing how you could manipulate an image pixel-by-pixel or by using various digital paintbrushes and effects. Morrow noted that Lumena created three-dimensional images, so at least you were “getting something for your money” versus other, 2D-only packages. Dowlen added the images made with Lumena rivaled those made used conventional airbrush painting.

Cheifet asked about creating hard copies of art created in Lumena. Dowlen said the best method was to put it onto film using the Kodak Ektachrome format. This required using a separate digital-to-film recorder that cost between $3,000 and $4,000.

Data vs. Information

Paul Schindler was bullish on the future of computer graphics in his closing commentary. He noted there was a difference between data and information. Data was just facts, he said, while information added context that made information usable in making decisions. As computers became cheaper–and humans more expensive–Schindler said human graphics departments were destined to be replaced by computers. So computer graphics needed to do a better job converting data to information.

Computer Industry Slows Down as Apple Descends Into Confusion

Stewart Cheifet presented “Random Access,” which is dated in June 1985.

- Industry experts said that IBM would not release its previously promised PC-2 computer anytime in the foreseeable future. Cheifet said there had been rumors for months that IBM would release such a machine based on the Intel 80286 microprocessor, fueled largely by price cuts on existing IBM models. But now, analysts believed those price cuts were simply designed to move existing inventory and there would be a “long wait” before the PC-2.

- Cheifet said “confusion continues to rain” at Apple, with rumors of massive layoffs, a buyout by Steve Jobs, and even possible hostile takeover attempts. (The graphic accompanying this story is an all-time classic.)

- Evidence of growing slump in the computer business was everywhere this week, Cheifet noted. Layoffs were announced at Wang Computers, Control Data Corporation, Grid Systems, and Advanced Micro Devices.

- Cheifet said one part of the computer industry that was booming was security. The United States Government had a program called TEMPEST, which modified personal computers to eliminate the radio signals emitted by the machines. These signals could be read to indicate what the computer was doing. The National Security Agency said a $3,000 computer could end up costing $10,000 after making the necessary modifications.

- Paul Schindler–accompanied by his four-year-old daughter–presented his weekly software review, this time for The Stickybear ABC, a program designed to teach the alphabet to preschool children. Schindler said his daughter loved the program, which came bundled with a book and stickers.

- Early reviews were in for Lotus Jazz. Cheifet said the software earned praise for its ease of use and graphics, but critics pointed to the lack of memory, slow access, and a lack of macros.

- At the recent Robots 9 robotics conference in Detroit, manufacturers showed off new robots with vision and force-sensing capabilities. Cheifet said these industrial robots could recognize parts in any position and tell when things were going wrong by feeling the extra pressure when something didn’t fit right.

- In the consumer robot market, former Atari executives Nolan Bushnell and Donald Kingsborough had each come up with competing computerized “pet robot” toys. Both men claimed they had already taken $75 million in orders for the 1985 holiday season.

- A New Jersey man became so addicted to the online CompuServe game MegaWars that he now faced prison time. The man stole a credit card number so he could stay online all night playing the space-themed game. Cheifet joked he may have won the interstellar war but lost the legal battle and now faced a five-year prison term and a $250,000 fine.

PDI Went from Making Super Bowl Ads to Hollywood Feature Films

The “Random Access” segment for this episode hinted at two subjects that would dominate the start of season three of Chronicles in just a few months–the overall slowdown of the computer industry and Steve Jobs’ ouster from Apple. Jobs’ departure would, oddly enough, lead to his taking a leading role in the growing market for computer graphics. In early 1986, Jobs acquired the computer graphics division of George Lucas’ Lucasfilm Ltd., which was reorganized as an independent company called Pixar. At the time, Pixar was not in the business of making motion pictures–Jobs acquired the division so that he could sell high-end graphics workstations based on Pixar’s technology.

The Jobs-led Pixar would later pivot to film and debuted its first computer-animated feature, Toy Story, in November 1995. But just a few weeks earlier, the annual Halloween episode of The Simpsons featured its own computer-animated segment, which was created by Carl Rosendahl’s Pacific Data Images. (Rosendahl was credited as an executive producer on the episode). PDI’s work for The Simpsons helped it to secure a relationship with DreamWorks SKG, the movie studio co-founded by Jeffrey Katzenberg, who also played a role in supporting Pixar as a Walt Disney executive.

DreamWorks initially acquired a 40 percent share of PDI as part of a deal to have the latter produce animated feature films and visual effects for the former. In 2000, DreamWorks acquired majority control of PDI and Rosendahl himself retired as the company’s chairman. Since then, Rosenhdahl’s most notable professional work has been as a Distinguished Professor of Practice with the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, where he has been since 2008.

Family-Owned Brøderbund Made Early Mark in Apple II Productivity Software

Although Steve Jobs’ pride and joy, the Macintosh, was widely touted for its high-resolution (albeit monochrome) graphics, it’s interesting that this episode pointed to the growing market for arts software for Jobs’ neglected stepchild, the Apple II. Dazzle Draw was in fact just one in a growing series of productivity programs developed by Brøderbund Software, which largely focused on the older Apple II platform in the mid-1980s.

Brøderbund was formed by brothers Doug and Gary Carlston in 1980. As Doug Carlston told the story in his 1985 autobiography, he was working as a lawyer in Maine in the late 1970s. On the side, he wrote a game called Galactic Empire for the Tandy TRS-80 in 1979. Carlston mailed the game to a number of software companies, including Scott Adams’ Adventure International. Adams and his wife agreed to publish Galactic Empire, and shortly thereafter Carlston decided to quit his law practice and write computer games full time.

Carlston traveled from Maine to Oregon, where his brother Gary lived, and after Gary managed to sell $300 worth of Doug’s games to a computer store in Washington, DC, the brothers started Brøderbund. “Brøderbund” is not a real word. The name was taken from a word used to describe one of the factions in the original Galactic Empire game. As video game historian Jimmy Maher explained in his own overview of the company, Brøderbund was “a mash-up of Danish and German — or an example of a sort of pidgin Danish, if you prefer.”

While Brøderbund may have started with Doug Carlston’s games, it actually gained far more notoriety (and market share) as a publisher of productivity and educational entertainment titles. One of the company’s earliest non-game offerings was Payroll, a payroll system for the IBM PC. The next year, Brøderbund published Bank Street Writer, a word processor for the Apple II, which became a major hit.

I couldn’t find any specific explanation for what led to the development and release of Dazzle Draw in 1984. David Snider, the program’s author, initially approached Doug Carlston and his sister Cathy (who was also working at Brøderbund) at a trade show in Chicago about a pinball game he was working on for the Apple II. In a 2013 interview, Snider said he was inspired by Bill Budge’s Raster Blaster, another early Apple II pinball game, as well as a recently released pinball table called Black Knight.

Snider was actually driving to Kansas City when he decided to stop in Chicago and attend the trade show. After speaking with the Carlstons at the Brøderbund booth, Snider showed the Carlstons his pinball game prototype and left his contact information. A week later, Doug Carlston called Snider and told him that Brøderbund would publish the game, which became known as David’s Midnight Magic. Snider said he went on to sign a contract with Brøderbund and remained with the company for the next 10 years. (Snider still works as a programmer today, creating apps for the iPhone and iPad as an independent developer based in Florida.)

Whatever its origins, Dazzle Draw proved to be another Brøderbund success story. According to one sales chart I found that was published by distributor Softsel in February 1986, Dazzle Draw was ranked the third best-selling home software product in the United States. Two other Brøderbund titles–The Print Shop and Bank Street Writer–were first and fifth, respectively.

Bernstein’s Journey from Tech Journalist to Tech Startup Founder

As for the Brøderbund executive featured on Chronicles, Ed Bernstein, he started out as a journalist in San Rafael, California. After writing a glowing review of Bank Street Writer in a June 1983 issue of InfoWorld, Bernstein joined the company shortly thereafter. A September 1983 column by Herb Michelson of the Sacramento Bee described Bernstein’s initial role at Brøderbund as that of an “editor” who played games submitted by independent developers, forwarding the ones he liked to a review committee for possible publication.

Later, Bernstein oversaw Brøderbund’s “new ventures” division, which according to video game historian Norman Caruso was initially created to publish Personal Preference, a board game created by yet another Carlston sibling, Don Carlston. This division basically took on products that were outside of Brøderbund’s core competency in computer software, which after 1987 was primarily games for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES).

As Caruso explained in a 2021 documentary for his Gaming Historian YouTube channel, Bernstein played a key role in what became one of Brøderbund’s most notable failures–the U-Force. This was a laptop-like device that employed infrared sensors, allowing a player to control the NES using only hand movements. The U-Force was the brainchild of a former Mattel executive, Dave Capper, who happened to know Bernstein socially. Bernstein and a team from Brøderbund attended a demonstration at the home of Bernstein’s engineering partner on the project. Caruso said Bernstein was “impressed” by the technology, but noted the project was still a risk for Brøderbund, which had no prior history producing hardware.

Despite these reservations, Brøderbund acquired the rights to Capper’s project–later dubbed the U-Force–and poured millions into development, production, and marketing. A redesigned U-Force prototype “was the star of the show” at the 1989 Winter Consumer Electronic Show in Las Vegas, according to Caruso. Bernstein himself helped to fuel the hype. He told a reporter for Gannett that “we could design spectacular new games for this system.” When pressed if any such games were actually in development, however, Bernstein replied, “Lots. How’s that for mysterious?”

The CES buzz helped to generate almost $100 million in pre-orders, Capper told Caruso. But production delays and a lack of software support–it turned out there were zero U-Force-specific games actually in development–combined with strong competition from Mattel’s Power Glove, ultimately doomed the project. Caruso said it was estimated that Brøderbund only fulfilled about $27 million out of the original $100 million in pre-orders. Brøderbund ended up selling off its entire new ventures division in 1990.

Bernstein also moved on from Brøderbund in 1990. After a brief stint at software developer Mindscape, Bernstein co-founded and served as CEO of his own company, Palladium Interactive, from 1994 to 1998. Palladium’s biggest claim to fame was a series of satirical programs released under its Parroty Interactive label, including Pyst–a takeoff on Brøderbund’s bestselling game Myst–and Microshaft Winblows 98, a lazy satire of Microsoft’s operating system and corporate culture. (If you’re interested in the latter program, I suggest this August 2020 video walkthrough from YouTuber Michael MJD.)

After the end of Palladium, Bernstein went on to found several other startups, including Photopoint, PhotoTLC, and Propell Technologies Group. He was most recently a partner in a San Francisco-based company called Salon Partners, LP, and apparently continues to work in as a media training and technology consultant.

Lumena Creator Started Out Working with the Man of Steel

Lumena was clearly the most advanced graphics package featured in this episode. Not surprisingly, it was also the most expensive, although not quite as pricey as the Quantel Paintbox. A 1989 review by Dr. Rodney Chang said that when Lumena was first introduced in 1983, a PC workstation setup with the software ran about $20,000. By 1986, however, InfoWorld reported that you could purchase a Lumena workstation based on the IBM PC XT–including a color monitor–for around $5,000.

Lumena was developed by John Dunn, a computer programmer who also held a master of fine arts degree. Dunn’s first job out of graduate school was with Atari, Inc., where he developed the game Superman for the Atari 2600. In a 2000 interview with Randy Ball, Dunn said Atari management reluctantly agreed to his request to program Superman on a 4 KB ROM chip–the standard was 2 KB at the time–because they “were afraid I would ‘go artsy’ and take a lot of time” to complete the game. Dunn said he got his 4 KB chip but was kept “on a very tight schedule” to ensure the game would come out not long after the release of the 1978 Superman film directed by Richard Donner. (Atari and the Superman franchise were both owned by Warner Communications at the time.)

After completing Superman, Dunn said he pushed Atari management to produce games with “a positive educational underpinning.” When management balked, Dunn left the company to pursue independent game development. While working on what he described as a “robot building block game,” Dunn said he found that the “graphics editor I made for the game was more interesting than the game itself.” This led Dunn to turn his graphics editor into a standalone computer painting program called SlideMaster, which was released by the computer manufacturer Cromenco.

Off of SlideMaster’s success, Dunn founded Time Arts, Inc., in 1982 to develop a new digital graphics program that he initially called EASEL but later changed the name of to Lumena. According to Rodney Chang’s review, Dunn left the day-to-day management of the company in the late 1980s and moved to Hawaii with his then-wife. Time Arts itself appears to have petered out in the early 1990s, and the Lumena software–which Dunn had continued to develop throughout the late 1980s–was acquired by another company, Western Imaging. Dunn later started another company, Algorithmic Arts. Dunn passed away in June 2018 at the age of 75.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of June 18, 1985.

- MacDraw was essentially an updated version of LisaDraw, one of the programs packaged with the ill-fated Apple Lisa. Mark Cutter is credited as the author of both programs. He worked at Apple until 1991 before moving on to a series of executive roles at a number of companies, most recently as chief technology officer at FoodChain ID.

- Marein Cremer, now known as Marein Cremer-Orre, currently works as a consultant and business coach in the German state of Bavaria.

- As noted above, this was the final episode of season two of Chronicles. It was also the final appearance of Robin Garthwait as a reporter. Wendy Woods will return for the start of season three.

- James Dowlen remains an active artist currently living and working in Oregon. According to Dowlen’s website, he’s done digital art work for high-profile clients in the entertainment industry and continues to perform private commissions.

- One of the “robot pets” created by Nolan Bushnell’s company was AG Bear, a talking teddy bear, which will be featured in a future Chronicles episode.

- Doug Carlston wrote in his autobiography that he asked David Snider about creating a “generalized pinball microcomputer construction set” based on David’s Midnight Magic. Carlston said Snider thought it wasn’t possible with the existing technology. Bill Budge, of course, did create Pinball Construction Set, the subject of an earlier Chronicles episode. Carlston tried to get the publishing rights to Budge’s program, but Budge of course ended up signing with Trip Hawkins’ Electronic Arts. Carlston didn’t seem to hold a grudge though, and said Budge deserved his fame as the “first software artist to become a pop star.”

- The New Jersey man charged with stealing credit card information was at the time a 19-year-old pre-law student at George Washington University. According to an Associated Press report, he used his computer to hack into the database of a “credit reference company,” identified customers with high credit limits, and opened accounts in their name, which he then used to fund his MegaWars habit. If you’re wondering why he needed so much credit to play a game, like many early online services CompuServe charged hourly access fees. The man ran up $3,750 in charges. He did not end up going to jail, however, and instead received three years probation, a $500 fine, and was required to make restitution to his victims.