Computer Chronicles Revisited 28 — The Tandy 1000 and Compaq Portable

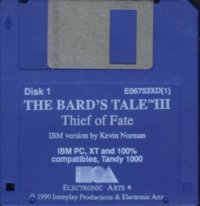

Purchasing software in the late 1980s often required the buyer to carefully read the label, especially if you owned a personal computer that purported to be “compatible” with IBM. Take this diskette for the IBM port of The Bard’s Tale III: Thief of Fate:

As you can see, the disk label states the game works with the “IBM PC, XT and 100% compatibles,” as well as the Tandy 1000. Tandy is the only compatible listed by name, as by this point–this was a 1990 release–the 1000 line was widely considered the gold standard for IBM compatibility.

This brings us to our next Computer Chronicles episode from January 1985, which focused on the Tandy 1000 and the state of the market for IBM “clones” or “lookalikes.” In the cold open, Stewart Cheifet stood in a computer store next to an IBM Personal Computer XT–the direct successor to the original PC–and noted the machine sold for around $4,000. He then showed off some of the IBM “clones” and said they typically cost less than the IBM computers yet claimed to run all of the same software.

In the studio, Cheifet said that when people asked him if they should buy an original IBM or a lookalike, his answer depended a lot on compatibility. But what does “compatibility” mean? Gary Kildall replied that in the case of hardware and software, compatibility meant that two things did the same thing–or more. That can be both a good and a bad thing. He noted that over 10 years ago, IBM set certain standards, such as the use of 8-inch floppy disks to distribute software. Today, there was a more complex situation where people were trying to emulate both IBM’s hardware and software. The whole industry was now effectively chasing the changes made by IBM.

Cloning Your Own IBM PC

Before getting to demonstrations of popular mass-market IBM clones, Wendy Woods presented a report on how some people built their own PC lookalikes. Over footage of an unidentified man building a PC clone, Woods explained that despite the IBM logo prominently displayed on every PC case, very few parts inside the machine actually came from Big Blue. In fact, she added, over 95 percent of the IBM PC was produced outside of the company. Aside from the motherboard, case, and power supply, the components came from many diverse sources, including Hitachi and Texas Instruments.

But why build your own PC? Woods asked. In becoming more “intimate” with the machine, she said, the user could learn about hardware functions and compatibility. More importantly, the do-it-yourself approach could save you about $1,000. Parts were cheap and could be picked up at a local electronics store. There were also manuals explaining everything from DIP switches to semiconductors. Woods noted the typical user would probably spend a great deal of time reading before doing any actual building.

Woods said there were other advantages to a DIY approach. If the user didn’t like the stock hardware, they could make their own improvements, such as installing a faster chip or a better disk drive, again for less money. The open architecture design of the PC made that possible. So should you build your own clone? Woods said it depended on whether you could trade time for money. The PC project demonstrated in the B-roll footage took about 2 weeks to complete–not including about 100 hours of research. But for a user willing to do some reading, and shopping, Woods said the advantages were undeniable.

Could Tandy Threaten IBM’s Dominance?

Ed Juge and David Bunnell joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first studio roundtable. Juge, the director of market planning for Tandy/Radio Shack, was there to demonstrate the Tandy 1000, a clone of the IBM PCjr. Kildall opened by pointing out that IBM had created a situation much like the mainframe industry where it set the standards that other people followed. In the last couple of years, that allowed IBM to take a significant piece of the PC market. So if IBM set the standard, why would anyone buy from a company other than IBM? Juge replied that the Tandy 1000 offered a price-performance advantage that IBM could not match. The 1000 was compatible with the PC but included the graphics and sound enhancements that were normally available on the PCjr.

Cheifet said the Tandy 1000 was advertised as a “mirror image” of the IBM PC. Did that bother Juge? Juge clarified that another model, the Tandy 1200, was actually the mirror image of the IBM PC XT. The 1000 was not a mirror of the XT as such. Cheifet retorted that this was a general notion, and what did it mean for the industry to simply advertise everything as being like an IBM. Juge held his ground and said Radio Shack did not advertise the 1000 as being exactly like the IBM. They were trying to leverage off the popularity of the IBM’s operating system–MS-DOS–and all of the software available for it. But they were not trying to do everything that IBM did.

Kildall said the IBM provided a base level that companies like Radio Shack were trying to enhance. Juge said that was right, they were bringing something else to the party. Kildall pointed to Compaq’s popular IBM compatible, which offered a degree of portability that the XT could not.

Cheifet turned to Bunnell, the publisher of PC World and Macworld magazines, and asked if the “obsession” with IBM compatibility was good or bad for the industry. Bunnell noted that first off, a truly successful compatible offered something different than an IBM PC rather than just a mirror image. That is why the Compaq was successful and there was a lot of excitement about the Tandy 1000. Bunnell further agreed with Juge that the important thing was that a compatible had to run the same software base. He also conceded Cheifet had a point in that if there was only one standard that everyone adhered to, it tended to inhibit creativity and innovation.

Kildall asked about the biggest potential threat to IBM’s position. Could any of the clones actually capture significant market share? Bunnell said he did not see any particular threat to IBM’s position. He did not anticipate a decline. But he noted that personal computers were used for so many different tasks that there was room for many different kinds of PCs. IBM could not cater to all of these users.

Kildall noted that if a clone was offering a popular feature, such as portability, IBM could still go in and take that market for itself. Bunnell agreed, noting that was the danger of playing the IBM compatible game. They had great efficiency in manufacturing and could come in and lower prices at any moment. That’s why some other compatible companies like Columbia Data and Eagle had fallen on hard times.

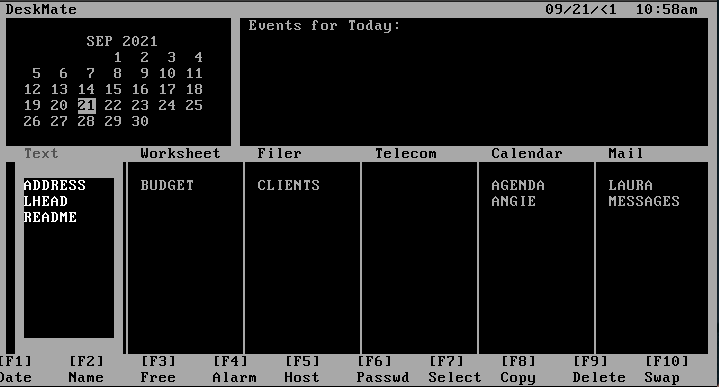

Cheifet turned to the issue of software. Specifically, he asked Juge about DeskMate, a bundled software package included with the Tandy 1000. If the main selling point of the 1000 was compatibility with IBM programs, then why does it come with its own software? Juge explained that Tandy actually built several families of computers. The IBM compatibles–or more accurately, the MS-DOS compatibles–were just one family. For example, Tandy also marketed a multi-user system based on Xenix, Microsoft’s UNIX-based operating system.

As for DeskMate, Juge said, it was a combination of six different applications–a text processor, worksheet, database, telecommunications, calendar, and electronic mail–that gave the user something to have immediately when they took the computer home. It also provided an easy way for Radio Shack salespeople to demonstrate the product, as DeskMate was available on all Tandy computer lines. And it was just nice to have something you could bundle with the computer that gave it some additional value.

Cheifet asked about the Tandy 1000’s compatibility with two popular IBM PC programs, Lotus 1-2-3 and Microsoft Flight Simulator. Bunnell demonstrated that Flight Simulator loaded just fine on the Tandy 1000. He explained that both Flight Simulator and Lotus called upon the machine’s BIOS, which was separate from the operating system and stored in the computer read-only memory (ROM). A real compatible like the Tandy 1000 therefore had to emulate that BIOS code without simply copying IBM’s software. That is why these programs were a common test for compatibility.

Cheifet concluded the segment by asking Bunnell about IBM’s strategy going forward. Did they really care about the clones? Bunnell said IBM’s approach was to have an open system that encouraged development of a lot of software for their computers. And as they increased the number of machines manufactured and improved the efficiency of their distribution system, IBM would then lower prices and take a bigger piece of the action. It would be foolish, Bunnell said, to think that IBM would not remain highly competitive and want to dominate the market, because they do.

IBM Not Fully Compatible with IBM

In her second report for the episode, Wendy Woods looked at issues of compatibility within the IBM computer line itself. She noted that IBM claimed the PCjr could run over 1,000 programs designed for the original PC. While she couldn’t test all of them, she did test a random selection of eight programs on an PCjr with 384 KB of RAM and a Legacy expansion unit.

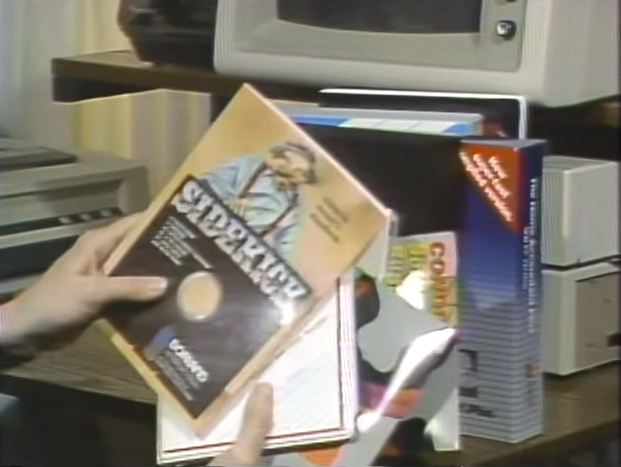

Half of the eight tested programs worked on the PCjr, Woods said, and half did not. Jim March, a computer salesman who assisted with the testing, told Woods that the first problem was the graphics display. One of the test programs, SPOC Chess Master, crashed in the middle of opening its graphics screen. Another program, Borland’s Sidekick came in two versions, one with copy protection and one without. Only the non-protected version worked with the PCjr.

March identified two other issues with PC-PCjr compatibility. The first was timing–anything involving the use of the computer’s clock could mess the software up. The second was conflicts created by where the software developer decided to load their program into memory. This was an especially “insidious” problem, March said, because there was no single way for the user to detect or guard against that problem.

The takeaway from this test, Woods said, was that consumers should make sure they see a program running on a PCjr in the store before buying it. And more importantly, make sure you can get a refund if the software proved to be incompatible.

The Legal Status of IBM Clones

For the final studio segment, Woody Liswood and David Grais joined Cheifet and Kildall. Kildall asked Liswood, a consultant with A.S. Hansen and an editor with the Whole Earth Software Catalog, to explain how a computer could be 99-percent IBM compatible. Could he provide an example of a program that would not run on a well-known compatible, in this case the Compaq Portable. Liswood demonstrated, as it were, a program called Scientific Plotter, which he said was one of the few that he found did not work on the Compaq. He noted this was a popular program in the Apple II world and recommended by the Catalog. But when trying to open it on the Compaq, the machine jammed just after displaying the title screen.

Kildall asked if a customer had any recourse if they purchased an incompatible program. Liswood said no, and when he ran into this problem with Scientific Plotter, the publisher said it only ran on the IBM PC XT and not the Compaq. Indeed, customer service was told to inform anyone who called that the software would not work without the original IBM BIOS.

This brought up the legal question of copying or recreating IBM’s BIOS. Cheifet asked Grais, an attorney with Grais & Richards, how anyone could legally make an IBM clone and advertise it as compatible. Grais explained what is commonly known as “clean room design”–although he did not use this exact phrase. Basically, Grais said as long as you could persuade a judge that you didn’t simply go to ComputerLand, buy a copy of IBM’s BIOS program, and copy it, you were okay. The way to do this was to have one person prepare a specification of what the program is supposed to do, while a second person–who had never seen IBM’s original software–wrote the program to meet that specification. As long as this second person did not copy any original IBM code, then the clone maker was probably safe from an IBM legal challenge.

Cheifet noted, however, that there were a couple of lawsuits, notably an IBM case against Eagle Computers, that alleged illegal copying of the PC BIOS. Why did these lawsuits happen? Grais replied that Eagle settled the IBM lawsuit immediately, so the public never learned much about the merits of the case. But you could probably figure that IBM called them on the phone just before filing the lawsuit and Eagle realized it didn’t have a strong defense.

Kildall pointed out that Apple recently received a patent for the pull-down menus on the Macintosh user interface. If patents like that were now being approved, could IBM patent something like its new TopView operating system? Wouldn’t that cause some real problems? Grais said he knew IBM did intend to seek patent protection for TopView. But the law regarding the patenting of the software was still “unsettled,” so it was difficult to say what the outcome would be. In contrast, the law of copyright was much more clear, particularly following Apple’s victory over an Apple II clonemaker, Franklin Computers, in a 1983 federal appeals court decision.

Kildall said that if the industry continued to follow IBM and that Big Blue’s response was to protect its user interface using copyright or patents, what would that actually do to the clone manufacturers? Grais said that was difficult to answer without looking at a particular program and the way it was protected. He noted that clonemakers had already found a way to legally emulate the BIOS of the IBM PC. Indeed, the Tandy 1000 had a perfectly legal and 100-percent compatible BIOS, and as far as anyone knew IBM had not raised any complaints. Nor did they about the Compaq Portable. The next challenge, Grais said, would be for the clone companies to find a way to legally emulate the BIOS in the new IBM PC-AT and possibly the TopView user interface.

Cheifet noted there were currently about 50 IBM clones currently on the market. Some had died and a couple were successful. What made the difference between a successful clone and a failed clone? Grais said that was a commercial question rather than a legal one. But he reiterated that if your clone had a copied IBM BIOS, then you would fail because IBM will sue you. But if you have a legally emulated BIOS, then it became a question of if you’re offering a better computer.

Cheifet asked Liswood about this from a user’s perspective. Liswood said that he personally bought the Compaq Portable because of its reputation. It had been around and had a larger user base–and it was portable, even at 38 pounds. He added that other factors like aesthetics and marketing played a role, but it cam down to the Compaq’s reputation for being the “most compatible of the compatibles.” Liswood said he used to take a Pascal-based program called GraphWriter to test IBM clones, and the Compaq was the only machine that could run it. So now he kept an IBM PC XT at work and a Compaq Portable at home.

Kildall noted the clone industry could benefit from changes to IBM’s video interface, which insulated applications programs from the graphics system. Previously, an IBM machine required graphics to work in a specific area of memory. Now, Kildall said clonemakers would have the freedom to move towards higher resolution displays.

Liswood then provided a demonstration of a software-based compatibility issue that can arise on a clone. He booted Sidekick–shown earlier in Wendy Woods’ compatibility test for the PCjr–which loaded a separate file manager for the machine’s hard disk. Liswood explained that both programs started out working well together on the Compaq. But they got in the way of other programs that wanted to run. Essentially, the Compaq crashed when attempting to multi-task with Sidekick loaded.

Kildall explained this was the tip of the iceberg as PCs moved into more multi-tasking and networking functions. Traditionally, PC programs were designed to run on simple, single-user systems where the program took over the whole computer. Now if you had one program running in a multi-tasking world with another, both programs tried to access the screen at the same time, as was the case when trying to run Sidekick with something else on the Compaq. Liswood reiterated this wasn’t a hardware issue, as this problem also affected the IBM PC XT. It was a matter of software incompatibility where multiple programs tried to use the same memory at the same time and lousing everything up.

Rooting for the Non-Clone PCs

Paul Schindler ended the main part of the episode with a commentary. He said he didn’t like the PC clones. IBM had set the standard not because it had a better product, but simply because it was IBM.

Schindler conceded that the personal computer market was in “turmoil and ferment” before IBM entered it. But that turmoil had an advantage in that there were a lot of people trying to give people more computer for less money. IBM simply waited and watched while many other companies–notably Apple–defined the personal computer market. Then IBM came in and used its traditional relationship with corporate buyers to suggest they only buy from IBM.

As a result, Schindler said that with the exception of Apple, all of the non-clone makers were dying on the vine. Schindler said he would never buy an IBM or IBM clone himself because he wanted to encourage innovation–and he thought the viewer should do the same. He said we should all root for the non-clone PC makers to be successful.

Apple’s 1985 Sequel to “1984” Ad Not Well Received

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which dates the episode in late January 1985.

- AT&T and Microsoft announced an “extended relationship” intended to establish the former’s UNIX operating system as a new industry standard. Cheifet said that at the recent UniForum conference in Dallas, AT&T said it would ensure its SystemV UNIX would be compatible with Microsoft’s Xenix. Intel, National Semiconductor, and Motorola also agreed to adapt their respective microprocessors to work with SystemV.

- UniForum was the first event held at the new Dallas Informart, a $100 million, 1.5 million square foot building designed to serve as a “permanent computer expo.”

- MicroPro sued American Brands, Inc., alleging copyright infringement of a number of programs, notably the popular word processor WordStar.

- The U.S. Department of Commerce issued a report that said the United States accounted for 70 percent of the world’s $18 billion software market. But with “proper copyright and trade policies,” the U.S. share could grow to 75 percent over the next two years, when the market was expected to be worth upwards of $55 billion.

- Paul Schindler offered his weekly software review, this time for TuneSmith/PC, which converted simple BASIC programs into playable music. Schindler was impressed with TuneSmith, particularly given the IBM Personal Computer was never meant to make music, as it only had a one-voice beeper speaker.

- Cheifet noted that bubble memory–a favorite technology of Gary Kildall from last season–may be making a comeback. Researchers at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pennsylvania said they had developed a new form of bubble memory that was 16 times more efficient than prior efforts.

- Cheifet said that police in New Jersey were experimenting with a new computer device that could purportedly perform an “instant brain scan” to help determine if a person was under the influence of drugs. The police said if successful, the device could be used as a possible supplement to traditional Brethalyzer tests in DWI cases.

- Apple announced a new project called Macintosh Office, featuring a $7,000 laser printer and the AppleTalk network, which Apple claimed would provide a low-cost means for linking users of Macintosh and MS-DOS computers.

- Apple made this announcement in a commercial aired during Super Bowl XIX. The “Lemmings” ad was considered a “letdown” after the company’s famous 1984 ad that aired during the previous year’s Super Bowl. Cheifet quipped the 1985 commercial hit with “about the force of the Miami offense” during its 38-16 loss to the San Francisco 49ers.

- In Fayetteville, North Carolina, the local phone company recorded hundreds of phone calls made in the middle of the night from an unoccupied building. Cheifet said it turned out there were two Coca-Cola vending machines that were programmed to automatically call the local distributor when they were empty. The two machines tried to call at the same time and got busy signals, so they just kept calling back all night long. Cheifet said the distributor took down the system for “debugging.”

- A Massachusetts-based software company developed a new program, Puppy Love, that depicted a virtual dog who could respond to the user and do tricks. The designers said that eventually users would be able to cross-breed their dogs with other “compu-pups.”

Tandy 1000 Revives Radio Shack’s Retail Fortunes

It’s a well-known story today that the Tandy 1000 managed to succeed where the IBM PCjr failed. David L. Farquhar offered a succinct account of what happened on his blog The Silicon Underground:

Unlike the PCjr, the 1000 came with a reasonable keyboard from day one, and had expansion slots and a second drive bay. If you wanted, you could expand a Tandy 1000 to match the IBM PC feature for feature, and it would cost less than a PC. If you didn’t, it was a usable home computer pretty much as-is, too, for around $1,200 including a monitor. A comparable PCjr setup cost about the same, since both units frequently went on sale.

Tandy charged less than IBM for the computer itself, but made quite a bit of it back on peripherals. Tandy’s monitors and printers cost about the same as IBM.

The Tandy 1000 wasn’t quite an exact clone of the IBM PCjr. Tandy made the decision that if it had to choose between PC or PCjr compatibility in the design, PC compatibility was the safer bet. The result was a computer that ran most PCjr games and most PC productivity software, unmodified. Combined with good marketing, the Tandy 1000 showed what the IBM PCjr could have been.

It also can’t be understated how much the Tandy 1000’s success meant for the fortunes of its parent company. A couple of months before the 1000’s November 1984 launch, the New York Times reported that Tandy’s computer business was “in the basement”:

The company last week announced its first quarterly earnings decline in six years. Its leadership in personal computer sales has been lost to the likes of International Business Machines and Apple Computer, whose strong marketing efforts and price cutting have attracted millions of new personal computer buyers - particularly business users - in recent years.

Most analysts say that Tandy went wrong by failing until last year to realize that it could no longer effectively sell computers in Radio Shack stores, which flourished as computer outlets in the days when the desk-top machines appealed mostly to hobbyists and buffs.

Two years later, in July 1986, the Times and the analysts changed their tune when it turned out that, uh, people still wanted to buy cheap computers at Radio Shack:

Analysts said that in introducing the inexpensive computers, Tandy was solidifying its position in the so-called clone market, in which a large number of domestic and foreign companies are making computer products similar to the International Business Machines Corporations’ and selling them at lower prices with more features. The analysts added that the new Tandy computers would put pressure on I.B.M. to lower its prices only weeks after the giant computer company slashed its wholesale prices as much as 18 percent.

“The approach of offering the consumer a real value is smart,” said Michelle Preston, a computer analyst for L. F. Rothschild, Unterberg, Towbin. “Tandy will be able to compete very effectively with the clone products,” she said.

Tandy would continue selling revisions to the original Tandy 1000 up until 1993.

Ed Juge (1936 - 2003)

Ed Juge passed away in March 2003 due to cancer. Juge worked in electronic retailing for more than a decade before joining Tandy/Radio Shack in 1978. He spent six years as the company’s director of computer merchandising before taking over as Tandy’s primary corporate spokesperson in 1984, a post he held until 1993. In the mid-1990s, he shifted away from corporate work to focus on media consulting for the computer industry as well as his two main hobbies, recreational vehicles and amateur radio.

David Bunnell (1947 - 2016)

David Bunnell was one of the early pioneers of computer media, founding or co-founding a number of publications, including Personal Computing, PC Magazine, PC World, and Macworld, the latter two of which continue to this day. Harry McCracken, a former PC World writer himself, wrote in an obituary for Fast Company following Bunnell’s death in 2016 that PC World and Macworld both represented a significant leap forward in tying tech media brands to specific computing platforms:

[PC Magazine] was such a success that multiple large publishing companies were soon interested in acquiring it. In fact, Bunnell and [co-founder Cheryl] Woodard thought they’d struck a deal to sell it to Pat McGovern of IDG, publisher of Computerworld and InfoWorld, when they learned that their financial backer had sold it to Ziff-Davis without bothering to tell them. They–and 48 of the magazine’s 52 staffers–responded by promptly quitting to found PC World for IDG. Its first issue was so thick with advertising that it set records.

With their next major IDG launch, Macworld, Bunnell and Woodard perfected the art of hitching a media brand to a computing platform. Thanks to a deal Bunnell hammered out with Steve Jobs, the magazine debuted on January 24, 1984, the same day as the Mac itself, and was promoted directly to new Mac owners via materials that shipped with the computer.

In 1985, Macworld the magazine spawned Macworld Expo, one of the few successful tech conferences ever aimed at consumers rather than industry types. By the time I started going circa 1988, it was held on both coasts and the Boston edition, which I attended, filled two convention centers.

Bunnell remained at IDG until 1988. He went on to start a number of additional ventures outside the world of tech media, including the Andrew Fluegelman Foundation, a charity named for a former Macworld editor that provided free computers to “poor, mostly inner city high school students.” This was part of Bunnell’s long history of social activism. For example, Victor F. Zonana noted in a 1987 profile for the Los Angeles Times that Bunnell never hesitated to use his position to advocate for minority groups that faced legal oppression:

Bunnell authored a sharply worded editorial in PC World and Macworld calling for the repeal of Georgia’s “archaic” and “oppressive” law against sodomy. The editorial was prompted by a letter from Georgia’s governor extolling the state as a center for high technology.

“The PC promise is to preserve and enhance the power of the individual,” the editorial thunders. The Georgia law “stifles the very progressiveness Gov. Joe Frank Harris hopes to promote” and “conflicts with the vision of personal freedom that compelled the growth of personal computers.”

The reaction was swift. About 5,000 letters poured in–more than the magazines had received in their entire history–and most of them were negative. A hundred subscribers canceled. And a handful of advertisers pulled a total of $20,000 of ads.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was first broadcast on January 24, 1985.

- The Compaq Portable, the other clone machine featured prominently in this episode, was already something of a legacy product, having been released in March 1983. The Portable was the first computer produced by Compaq and while it is often described as the first “100 percent” IBM compatible, former Compaq employee Paul Dixon has said that nobody within the company, or at least in the engineering department, ever made such a claim and that the actual degree of compatibility was “a moving target.”

- Given the legal discussion over BIOS and copyrights during the segment with David Grais, it’s worth pointing out that Stewart Cheifet was once a practicing attorney. He graduated from Harvard Law School and worked as a lawyer for the news divisions of ABC and CBS in the 1960s before moving into journalism.

- Software patents remain a controversial and unsettled area of the law even to this day.

- David Grais still practices law at Grais & Ellsworth, a New York City firm that represents plaintiffs in securities and financial litigation.

- I don’t have much to report on what became of Woody Liswood. The company he worked for at the time of his Chronicles appearance, A.S. Hansen, was a human resources consulting firm. Hansen merged into another firm in 1986. Beyond that, there are some scattered writings on computer topics by Liswood dating from the late 1990s, along with references to him teaching at colleges in California and Colorado.

- Shugart Associates was, of course, the first disk drive company founded by Alan Shugart, who later formed Seagate Technology and previously appeared on Computer Chronicles to discuss the future of his beloved 5.25-inch floppy.

- Before starting his various magazines, David Bunnell worked for Adam Osborne, a prior Computer Chronicles guest. In fact, Osborne appeared in his episode with Lore Harp, who married Bunnell’s boss at IDG, Pat McGovern.