Computer Chronicles Revisited 29 — Locksmith, PC-Talk, and Frankie Mouse

In the last episode, Wendy Woods mentioned that during her testing of IBM PC software compatibility with the PCjr that only the version of Borland’s Sidekick without copy protection worked with the latter machine. The version with copy protection was incompatible with the PCjr.

You might wonder, then, why anyone would have purchased the copy protected version in the first place. The answer was likely price. According to Borland’s advertising from the time–early 1985–the protected version cost $55, while the non-protected version ran $85.

Copy protection, of course, referred to a number of different methods used during the era of disk-based software distribution to prevent users from making additional copies–and possibly giving away or selling those copies to other potential customers. The industry took to referring to the practice of unauthorized copying as “software piracy,” which was the subject of this next Computer Chronicles episode.

“Why Did Software Cost So Much?”

For the cold open, Stewart Cheifet stood in front of a literal pirate–well, a wax figure of one displayed a Madame Tussands in San Francisco. He quipped that in the old days, a pirate looked like this figure and stole treasury, jewelry, gold, and silver. But today a pirate didn’t need an eye patch, a sword, or even a wooden leg. All you needed was a floppy disk and a little ingenuity.

In the studio, Cheifet asked Gary Kildall–himself the CEO of a major software company, Digital Research–just how serious was the problem of software piracy. Kildall replied it was very serious. The problem was that as a software producer, you couldn’t tell how much you were going to sell versus how much was going to be stolen. As a result, prices went up to make up for that difference. But if we could control piracy, he said, then we would know how much to sell and the industry would stabilize at a lower price level–much like the record industry.

Wendy Woods then presented her first remote segment, narrating over some B-roll footage of an unidentified software company (I think it was MicroPro, the company behind WordStar). Woods said that behind the discussion of the rights and wrongs of software piracy, there was a recurring question: Why did software cost so much? Except for the box it came in, commercial software looked like any other floppy disk. But for the publisher, the production cost of that disk was easily measured.

The biggest expense, Woods noted, was program development. A top word processing program could take 18 months of development time and require a team of 60 people. This team has to perform a number of tasks, including developing source code, user screens, help systems, and manuals. Indeed, prestigious software houses stressed their documentation and on-screen tutorials as part of their extensive customer product training.

Woods said the impetus for a product’s design came from a large marketing department. Advertising, package design, and merchandising all added another layer of cost. And when you factored in disk reproduction, typesetting, printing, and distribution, the overall cost of getting the program to the consumer rose to several million dollars.

Woods noted that to an advanced user who buys software based on word of mouth or by trying out a friend’s copy, the elaborate ad campaigns and customer coddling might seem like overkill. On the other hand, a first-time computer user may demand it. In any case, she concluded, the expenses were considerable and genuine–but for the user, that didn’t make the prices of software any easier to pay.

Activision Executive Lectures Other People About Having “Ethical Blinders”

Back in the studio, Mark Pump and R.L. Smith McKeithen joined Cheifet and Kildall. McKeithen was an attorney and the general counsel for software developer Activision. Kildall noted that Activision had traditionally been in the business of producing ROM cartridges for video game consoles (such as the Atari 2600), but the company had now moved into disk-based computer software. Kildall asked McKeithen how he–and Activision–viewed disk piracy. McKeithen replied it was a matter of Activision’s intellectual property being ripped off by people who hadn’t put the intellectual or financial investment into its creation.

McKeithen claimed it took between 1,500 and 2,000 hours to create a piece of quality software and that was an investment just like the one that an author made in writing a book or a director put into making a movie. So when someone took that product and tried to market it for pennies on the dollar, it meant the creator of an Activision game–such as Ghostbusters’ David Crane–was working for nothing.

Kildall asked if there was any difference between someone who copied and resold software versus someone who simply gave a copy to a friend. McKeithen said he made no distinction. Both types of people suffered from “ethical blinders” in his view. McKeithen said it was as if he took a Porsche that he never wanted to drive but slipped past a security guard. Even if he didn’t drive the care, or he gave it to a friend, that would still be stealing. And the same thing was true for a company like Activision when someone used its software in an unauthorized manner.

Cheifet then turned to Pump, whose company sold a disk copying program called Locksmith, and asked if users sometimes had a legitimate need to make copies of a program. Pump said without a doubt, they did. If they used an original copy that became unusable, then they were left without a program that their business might depend on for its daily operations. Kildall added that there was also a basic need that some people had to copy a program from a floppy disk to a hard drive.

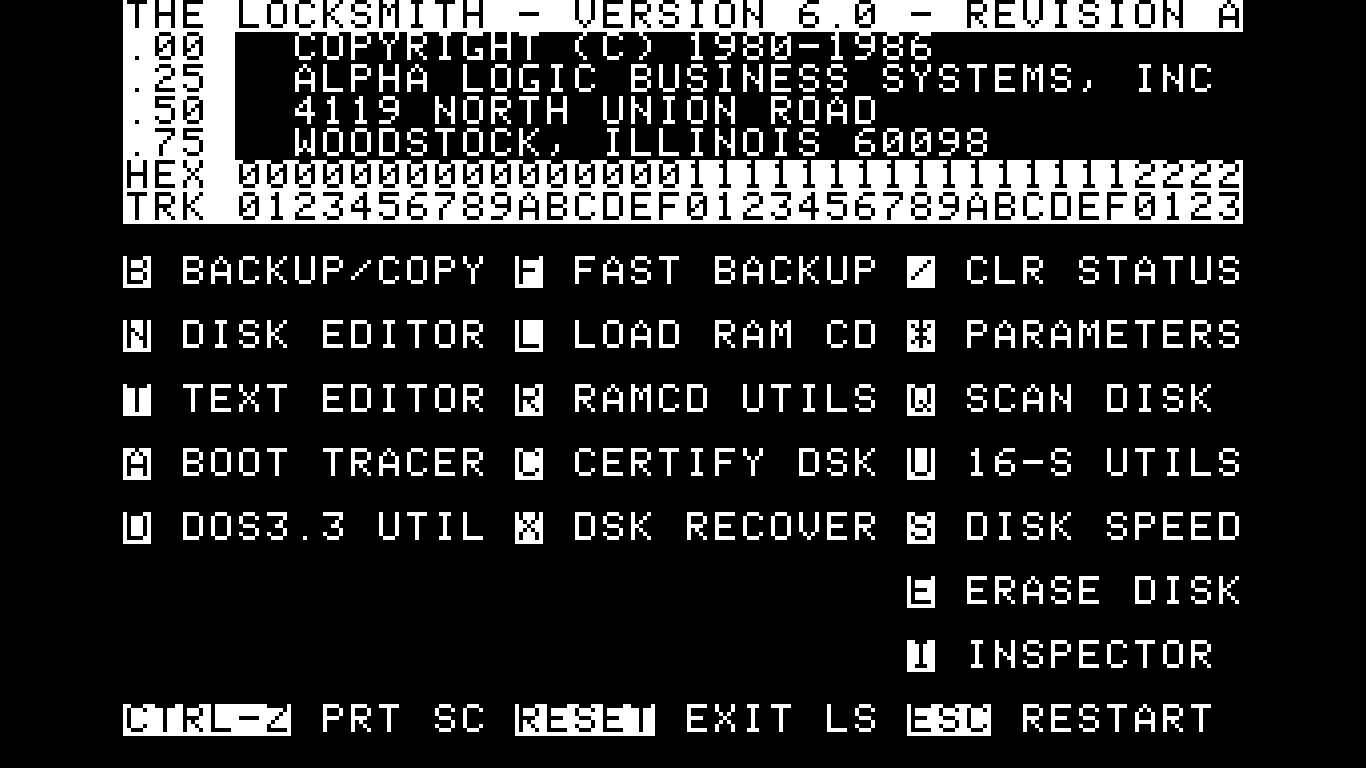

Pump then provided a demonstration of Locksmith using an Apple II with two attached disk drives. He explained it was a program that made an identical copy of the original disk. It did not “break” any copy protection on the original disk as it made a bit-for-bit copy, thereby retaining any copy protection, copyright notices, and serial numbers.

Pump noted that Locksmith was not a very fast utility. It took between 8 and 10 minutes to make a backup copy. This did not lend itself easily to commercial pirates who needed to make copies much faster. Still, Kildall pointed out that an 8-minute backup was a lot cheaper for users than paying $40 for an extra original disk. Pump said the idea was that a user would make a backup, store the original away, and then use the backup. That way, when the backup became unusable, you would have the original to make another backup.

Kildall clarified that Locksmith then was not intended for use as a piracy tool. Pump said in the product’s manual and advertising, it was made clear that users were only to use Locksmith for legal purposes. Of course, there were people who used it for piracy, even though there were much better ways to pirate software than Locksmith.

Cheifet asked McKeithen for his reaction. McKeithen said the problem with a product like Locksmith was that it facilitated people getting into stealing. It made it much too simple. If, in fact, a user of Activision’s products had a problem with their original disk, they could call a toll-free line or send the damaged product in for a replacement. Activision offered a 1-year warranty. He added the company received over 3,000 pieces of mail per week from users who wanted to know about upcoming products. These users had formed a bond with Activision, which the company would not ignore by not giving them good service. And all of the responsible software manufacturers followed that same trend. So McKeithen saw no need for a product like Locksmith in the event of someone having a damaged product they wanted to use.

Kildall pushed back a little, noting software providers weren’t allowing for the possibility of legitimate backups. He noted he ran into this problem himself, as there were programs he could not get onto his hard disk. McKeithen asked if Kildall had talked to the manufacturers about such problems. Kildall said sure he did, but they replied they didn’t want to give up control over distribution due to fears of illegitimate copying. McKeithen acknowledged there was a tension in the system, but the problem with a product like Locksmith and the wider-than-Activision-would-like use of illegitimate copies was that in the long range it would spoil the production of creative intellectual property for everyone. And that, he said, was a zero-sum game.

Cheifet asked Pump if he had any feedback about how customers used Locksmith. Pump reiterated that even without programs like Locksmith, software piracy would still exist. Sophisticated “hackers” didn’t need such programs. They had the technical expertise to break or remove copy protection from software without actually copying the original disk. Kildall noted that may be true for some pirates, but he said that even his 15-year-old son and his friends were now copying software. And he didn’t think that would be possible without programs that helped them unlock protected disks. Pump added that one of the largest users of Locksmith was schools. Educational software was not cheap, and teachers were reluctant to take their only copy of an expensive program and put it into their student’s hands, allowing it to either be stolen or damaged. So most schools that purchased Locksmith used it to archive and make backup copies of the original disks.

Software Industry Strikes Blow Against Teen Pirates

The third segment began with two new guests, John Draper and Neil A. Smith, who joined Cheifet and Kildall on the set. Cheifet noted Draper was once known as a pirate who went by the name “Cap’n Crunch” when that term referred to stealing long-distance phone calls rather than software. Today, Kildall said Draper was now a software vendor as the author of the IBM PC word processor EasyWriter and other programs. So how did Draper feel about modern software piracy? Draper said it was definitely a problem. He reiterated the point made throughout the episode that software was very expensive because programmers couldn’t work for nothing. He noted one alternative was “freeware,” which eliminated many of the problems associated with copy protection.

Kildall pointed out that freeware had the problem of support. Draper agreed, noting that you would only provide support for those users who actually mailed in their $20 or $30 checks to pay for a license.

Cheifet then asked Smith, an attorney who represented the recently formed Software Publishers Association (SPA), if he agreed that the cost of software was a problem. Smith said it was something of a chicken-and-egg problem. If you looked at the marketing of software, you found that one reason it had to be sold at high prices was to recoup development costs. If the manufacturer could count on everybody who used the program to buy a copy, that cost would drop dramatically. In many cases, however, he thought people were fooling themselves into blaming high prices for piracy. If that cost could be spread out, prices would be more like music records that cost $10 each.

Cheifet noted that Smith and the SPA had recently shut down a commercial software piracy group called the West Coast Computer Connection. Smith said this was one of the more “brazen” operations he’d come across. This group actually distributed a multi-page catalog listing hundreds of pirated programs for sale. He noted that one of those programs was actually Locksmith, which itself was copy protected and thus subject to piracy.

Cheifet asked about the ultimate fate of this piracy group. Smith said it turned out to be some “juveniles” and he visited with them and explained the seriousness of what they were doing. The SPA ultimately obtained a written agreement from the juveniles to “cut it out.” Smith noted there were much stronger remedies available under the law.

“Freeware” as an Alternative to Anti-Piracy Measures

Following up on John Draper’s earlier mention of “freeware” as an alternative method of distributing software, Wendy Woods presented her second remote, featuring Andrew Flugelman’s home-based software company, Headland Press, which produced a non-protected communications program called PC-Talk. Woods noted that not only was there no copy protection on PC-Talk, the user could freely make and distribute copies.

Flugelman told Woods that what he had done was simply address the whole notion of copy protection and piracy in a different way. Rather than restricting access to the program and appealing to people’s dishonesty, he was giving wider access to the program and appealing to the user’s honesty. Woods said about 1 out of every 10 users who copied PC-Talk not only paid the suggested registration fee of $35; they also sent letters of appreciation to Flugelman.

But what did this freeware model mean in terms of support, which was usually the biggest part of a software company’s budget? What did Flugelman do if people hadn’t paid for the program? He told Woods that they did better business by giving out the information, and if someone was using PC-Talk and hadn’t paid, by helping them to use the program they were more likely to pay. Woods said that Flugelman thought the rest of the industry could take a lesson from his approach. He received important feedback, business, and appreciation because of his philosophy. And while Flugelman wasn’t getting rich, he did receive a surprising amount of gratitude.

“Basically, It’s Just for Fun and Recognition.”

Back in the studio, Cheifet, Kildall, and Smith were joined by a teenage software “pirate” identified only by the handle “Frankie Mouse.” Kildall offered a disclaimer that by allowing Mouse to demonstrate software piracy techniques, they were not condoning it all. But he said this was a rare opportunity to see what pirating was all about.

Mouse logged into an online bulletin board used by hackers that displayed a list of text filed that provided information on how to commit software piracy, such as “Basics of Cracking 101.” He said that if you didn’t already know how to pirate software, these files would teach you. Mouse clarified that he did not write these how-to files. Someone else wrote them and they were now available throughout the country on different boards.

Kildall asked how many people were involved in these kinds of bulletin boards. Mouse said it depended on the board. Some had as few as 100 members, while others might have between 2,000 and 3,000 users.

Cheifet asked if it was possible to use the board Mouse had logged onto to actually get a piece of pirated software. Mouse explained that there were separate online repositories known as AE Lines used to actually download pirated software. These were not bulletin boards. Rather, they allowed the pirate to call a computer and download programs where the copy protection had been cracked.

Kildall asked Mouse why he downloaded pirated software. Mouse said that unlike the West Coast Computer Connection, he and his friends never engaged in piracy for profit. He said, “Basically, it’s just for fun and recognition.” If you mentioned a popular handle such as “Mr. Crackman” to any pirate, they would know who he was–not personally, but they knew his work. Kildall suggested that it was basically pirating for the fun of cracking a program. Mouse said yes, it was like a game. You felt like you were outsmarting the software makers.

Kildall asked Mouse if there were any moral issues he worried about with respect to piracy. Mouse said you could not deny that this was stealing. You didn’t pay for the software and now you had it. At the same time, he really couldn’t say how much the software companies lost in revenue, because a copied program was like free advertising. He noted that among his group, they had a “code of honor,” meaning that if they used a program a lot and liked it, they would go out and purchase a legal copy to obtain the manuals and support.

Cheifet asked Smith for his response to Mouse’s statements given that he represented the software publishers. Smith said this was both a moral and a legal issue. He reiterated that when people used software without paying for it, that meant software was a lot more expensive. He said that was an economic issue–if everyone just paid a small amount, we probably would see dramatic price drops. In terms of the legal issue, Smith said he was happy Mouse admitted his actions were stealing. Smith explained that copyright infringement is a crime under U.S. law punishable by up to 1 year in prison. Additionally, the copying of software company’s trademarks is a separate criminal offense punishable by up to 5 years in prison.

Mouse then demonstrated a pirated copy of DB Master, a popular database program for the Apple II. He noted this particular software was “protected like crazy.” But his pirate group managed to remove the protection so that it could be copied from a BASIC prompt. Indeed, Mouse said he was surprised to learn that DB Master itself was largely written in BASIC, given that most commercial software was written in assembly language.

Kildall asked Mouse what it would take him to buy a program rather than steal it. Was there some incentive the manufacturer could provide? Mouse repeated his earlier statement that if there was a program he used a lot, he would buy it for the manuals and support. So he said the answer was for companies to simply put out good manuals and support their products.

Cheaper Software Is the Solution

Paul Schindler wrapped up the episode with his traditional commentary. He said the question of whether software piracy was moral was hard to answer. Obviously, piracy was illegal and the definition was simple: It’s piracy if you gave away a commercial software program. Yet most people thought piracy was only immoral if you sold the software. Those two views were irreconcilable, Schindler said, and caused a great deal of controversy within the software industry.

As a result, developers were constantly looking for ways to stop piracy. One of the most common–and dumbest, in Schindler’s opinion–was copy protection. It caused a lot of problems for users. Even worse, copy proofing addressed the symptoms and not the cause of piracy. And as far as Schindler was concerned, high prices caused piracy. He understood that Lotus 1-2-3 cost $700 because the developers wanted to make their money back. Corporations could afford prices like that, but private individuals could not. So whether or not software piracy was moral, expensive software was pirated a lot more frequently than cheap software. Schindler said the ultimate solution to piracy was thus for developers to find a way to make cheaper software.

The First Online Dating Service?

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which dates the episode in late January 1985.

- The Internal Revenue Service was looking into electronic filing, including the possibility of letting individuals send in their tax returns on a floppy disk. One IRS analyst said electronic filing could happen within the next 5 years.

- Meanwhile, software stores were filling up with tax preparation programs. Cheifet said there were at least 50 such programs now on the market, ranging in price from $50 to $300. Some programs simply helped you fill out returns while others offered more advanced tax planning. The five most well-known tax programs for the IBM PC and Apple II computers were:

- Tax Preparer (Howardsoft, $295)

- Softax (Design Trends Ltd., $199)

- PC TaxCut (Best Programs, $199)

- Tax Advantage (Continental Software, $69.95)

- Tax Wizard (Gamma Productions, $64.95)

- The IRS also said it would crack down on the use of tax deductions for home computers. Under revised regulations, a person could only take the full deduction for their PC if they used it at least 50 percent of the time for legitimate business purposes. Cheifet added that using a computer to analyze your personal investments would not count towards that 50 percent.

- Businessweek reported that employers were now warming to the idea of using online databases to search for prospective employees. There were at least 5 such online job databases now in operation.

- Cheifet said American manufacturers were “poised for the impending invasion” of Japanese personal computers using the MSX architecture but nobody seemed that worried. Industry analysts seemed to think the Japanese machines would offer “too little, too late,” noting that they had already received a “cool reception” after being introduced in Europe in 1984.

- Paul Schindler returned for his weekly software review, this time of the game Night Mission Pinball, which he described as the “finest physical simulation of a game” that he had ever seen.

- Cheifet said that Commodore Business Machines planned to layoff 500 workers from its manufacturing plants in Pennsylvania and California following slow Christmas 1984 sales.

- Hewlett-Packard planned to release an upgrade to its 110 Portable computer. Cheifet said the new model would have a 24-line display, 512 KB of RAM, and cost under $2,000, although it would not include any bundled software. (This machine would be known as the HP 110 Plus.)

- According to a survey by Software Access International, the average computer owner spent about 12.2 hours per week on their PC, dividing that time equally between work and gaming.

- COMEX, the New York Commodity Exchange, was now selling a computer simulation of commodities trading, which it hoped would encourage people to enter the field.

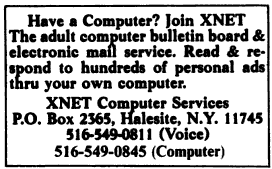

- Finally, New York magazine announced a new electronic mail service, XNET, that provided an online bulletin board for personal ads. Cheifet said about 300 people had already signed up for the service. (The service cost $25 for the initial subscription plus $5 per month to rent the election mailbox.)

Andrew Flugelman (1943 - c.1985)

In the last post, I mentioned that the late David Bunnell started a foundation in honor of Andrew Flugelman, who turned out to be a featured subject in this episode. Flugelman was the founding editor at both PC World and Macworld, where Bunnell was the publisher. He also became widely known as the father of “shareware,” which he referred to as “freeware.” Benj Edwards clarified the confusion over the nomenclature in a recent article for How-To Geek:

In 1982, Andrew Fluegelman created a telecommunications program called PC-Talk on his new IBM PC and began sharing it with his friends. Before long, he realized that he could put a special message inside the software asking for a $25 donation in return for future updates to the program. (Fluegelman called his concept “freeware,” but he reportedly later trademarked the term, leading to its limited use in the industry. The term was redefined after his death in 1985.)

Indeed, about six months after this Chronicles episode aired, Flugelman disappeared. He was never seen again and is presumed dead. According to a September 1985 report in PC Magazine,

Flugelman had been reported missing on July 8. His 1982 Mazda was found on July 11, abandoned near the north end of the Golden Gate Bridge. Tiburon police, still treating his disappearance as a missing-persons case, found a note in Flugelman’s car but say its contents were “inconclusive.”

A memorial service was held in White Plains, N.Y., by Flugelman’s relatives on July 14. In San Francisco, a service for Flugelman was held on July 19.

In the years following Flugelman’s presumed death, the distribution of software as freeware/shareware became more commonplace. As Benj Edwards noted, the same bulletin board systems used by software pirates also “represented an alternative distribution channel” for legal shareware. This eliminated a lot of the overhead costs associated with traditional software development and marketing. Of course, the rise of the commercial Internet and open-source software models during the 1990s largely relegated shareware to restricted “demos” of software as opposed to fully fledged programs.

Is Backing Up Software Legal?

Since my day job is writing blog posts for law firms, I would like to clarify one issue that came up in the episode. Smith McKeithen never actually came out and said that it was illegal for users to make backup or archival copies of their legally purchased software. That’s because he knew such behavior was perfectly legal. In 1980, Congress amended the Copyright Act to state that a person who purchased a legal copy of a software program did not infringe the author’s copyright by making an additional copy either as “an essential step in the utilization of the computer program in conjunction with a machine” or if the additional copy was “for archival purposes only.”

In other words, copying purchased software from a floppy disk to a hard drive was not against the law, either in 1985 or today. Companies like Activision may have actively fought against the practice initially, but by the end of the 1980s hard drives were in wide enough use that this largely ceased to be an issue.

It’s also worth noting that not all software companies offered replacement disks as a form of customer support. Donald W. Larson, who worked for Omega MicroWare, the publisher of Locksmith, addressed this point in a 2000 online forum post:

Visicalc was the number one program that users bought Locksmith to copy. In those years gone by, many software publishers would not provide a backup or replacement copy of software if the disk became unreadable. Because the Copyright law allowed a user to create a backup copy of software for their own use, Omega MicroWare had a fantastic market niche.

However, we followed a policy and would not publish Locksmith program parameters for publishers that provided a free backup disk or replacement policy for registered users. Many CEOs called me to complain about Locksmith parameters until I told them about that policy. Some changed their tunes afterwards and some continued to complain.

I wonder if Larson ever took a call from McKeithen.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an initial broadcast date of January 31, 1985.

- R.L. Smith McKeithen practiced law for more than 30 years before retiring in 2015. After leaving Activision in the late 1980s, he served as general counsel for a number of other companies, including Silicon Graphics, Inc.

- McKeithen was also a staff attorney for the House Judiciary Committee’s 1974 impeachment inquiry into President Richard Nixon, where his colleagues included future Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and future Massachusetts Governor Bill Weld.

- The other featured attorney in this episode, Neil A. Smith, is still active in the profession. He was a partner at Limbach, Limbach & Sutton for 25 years. In 2012, he was appointed to a one-year term as an administrative patent judge with the Patent Trial and Appeal Board of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Since 2018, Smith has been “of counsel” with the San Francisco firm of KB Ash Law.

- Actually, the late Andrew Flugelman was also a licensed attorney in California. Together with Stewart Cheifet, that makes four lawyers in this episode, which has to be some sort of record.

- Unfortunately, I could not track down any reliable information on the whereabouts of Mark Pump. His Illinois-based software company, Alpha Logic Business Systems, dissolved in 1989.

- As you might expect, I also have nothing to report on “Frankie Mouse.” The pseudonym may have been a reference to a character from Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

- In a 2011 post, tech writer Robert X. Cringely claimed that Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak was the actual creator of Locksmith. Cringely said Woz wrote the program to defeat the built-in copy protection that he himself had designed into the Apple II disk drive. I can’t find any independent collaboration of this story, and David M. Alpert, the publisher of Locksmith, told PC World in 1985 that Mark Pump was, in fact, the program’s author.

- That said, if Woz was involved with Locksmith, it would not be out of character, given that he and Steve Jobs were both inspired by John Draper’s telephone piracy–also known as phreaking–in the early days of their friendship, a story recounted by Phil Lapsley for The Atlantic in 2013.

- As for Draper, I don’t have much to say about him here. You can read about his fate in this 2017 Buzzfeed report.

- Having attended an underfunded elementary school in the late 1980s, I can confirm that students were almost always given legally dubious copies of software to use in the Apple II computer lab.

- The Software Publishers Association–today called the Software and Information Industry Association–started in 1984 as an anti-piracy industry group. It will also be a presenting sponsor of Computer Chronicles in future seasons.

- Since I haven’t mentioned it yet, this season’s presenting sponsor is McGraw-Hill, the publisher of Popular Computing magazine.