CCR Special 7 — BrainBank, CBS Software, and Murder by the Dozen

In the studio introduction for the 1986 Computer Chronicles episode on computers and law enforcement, Stewart Cheifet and Gary Kildall looked at an educational game, Murder by the Dozen, running on the Macintosh. BrainBank, Inc., created the game for CBS Software. Murder was actually one of two BrainBank games marketed by CBS under the name Mystery Master, the other being a sequel called Felony!

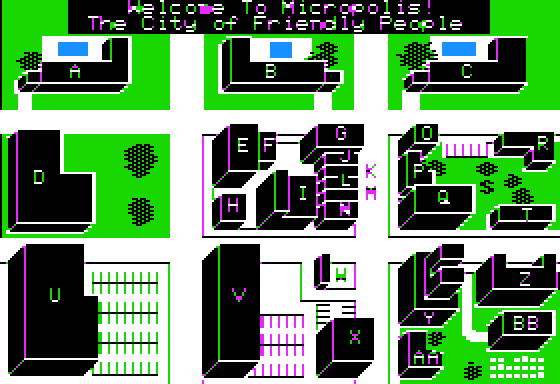

The two games essentially played the same. Each came with 12 murder mysteries for a group of between 1 and 4 players to solve. Imagine Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? but multiplayer and confined to a single city. Each player must visit various locations around the fictional city of Micropolis and gather clues by selecting items from a menu.

Actually, Murder predates Carmen Sandiego by a few years and has a more sophisticated menu system. Both games relied on an external book for gameplay. Carmen Sandiego famously came with the World Almanac so that players could look up geography-based clues and determine where to travel next to search for their suspect. In Murder, the game manual itself provided the necessary supporting text.

Indeed, while you could win Carmen Sandiego without using the almanac–assuming you knew a lot of geography trivia–Murder was unplayable without the accompanying Clues book. This was because when you selected a menu item in the game, it returned one or more numbers. These numerical “clues” corresponded to text entries in the book.

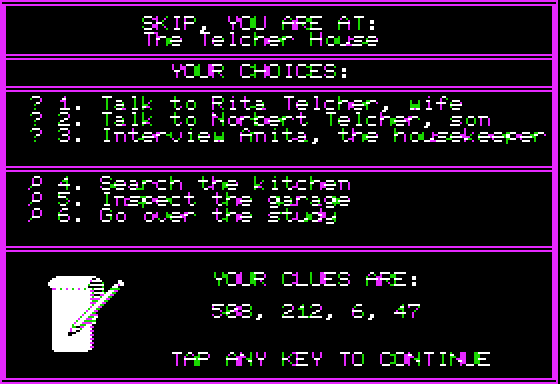

For example, the first case in Murder required the player to solve the murder of a local industrialist, identifying both the murdered and their motive. In the first menu there were six options, which either interviewed a witness or searched a location in the victim’s house. If you selected the first option–talk to the victim’s wife–the program gave the player four numerical clues: 508, 212, 6, 47.

Looking at the first number (508) in the clues manual, it reads: “I’m not too unhappy. He left me well off and I couldn’t stand him anyway.” The next clue (212) continues, “I can’t imagine who’d want to kill him.” The final two numbers (6 and 47) simply read, “No clue.”

The use of the printed manual–passed around between turns–made it possible for multiple players to try and solve the mystery individually. As each player selected menu options they also accrued in-game time. Carmen Sandiego had a similar mechanic, although in that game the hours counted towards a final deadline to solve the mystery. In Murder, the hours elapsed determined play order: The player with the fewest hours at the end of each turn would start the next round.

After 20 minutes of game play, all players could access a “Crime Computer.” This was the point where a player could attempt to solve the crime. Similar to Cluedo, if the player offered an incorrect solution, they lost and were out of the game while the remaining players continued to try and solve the case. Murder didn’t use a Clue-style envelope to hide the solution. Instead, there was a Solutions book that required the use of a red decoder film. Again, this allowed the player making the guess to read the solution without spoiling it for the others.

The Eternal Battle Against Copy Protection

Obviously, the necessary use of game manuals and decoders to play the game also provided a measure of copy protection for Murder. As Paul Schindler’s software reviews reminded Chronicles viewers on a weekly basis, copy protection was still a common practice in the software industry at this time, often to the frustration of users wealthy enough to afford a hard drive. The manual for Murder offered a somewhat conciliatory tone on this issue, explaining that under U.S. copyright law it was not considered infringement for a purchaser of a program to make “archival copies” as an “essential step of in the utilization of the computer program”–provided any such copies were destroyed if the user got rid of their original disk or its host computer.

Of course, Murder still had on-disk copy protection on top of the need to use the manuals. But even at the time, such schemes were not difficult to defeat. Issue 29 of Computist–a magazine dedicated to cracking copy protection on Apple II games–contained instructions on how to beat the copy protection on Murder simply by typing a couple of lines into a DOS monitor program.

CBS Foray Into Computer Software Fizzled Out, Like It Did for Most Entertainment Companies in the 1980s

Murder was initially released for the Apple II and Commodore 64 in 1983 and for the Macintosh and MS-DOS in 1984. As previously noted, the publisher and distributor was CBS Software. This was a division of CBS, Inc., which in addition to the famous television network also owned a large publishing division, Holt, Rinheart and Winston (HRW).

CBS launched the software division as part of HRW in 1982 when the home computer market was bustling. Within three years CBS Software marketed approximately 60 titles for the Apple, Commodore, IBM, and Atari 8-bit computers. (Based on the catalog I reviewed, Murder was the sole Macintosh release.) Most of the CBS titles focused on edutainment for young children and test prep for college-age students. Murder was one of the few titles aimed at adults–the catalog quipped, “Mom think she’s Miss Marple since solving a case in Murder by the Dozen.

By 1985, however, the home computer market was in a downturn and CBS was financially struggling. The company faced an (ultimately failed) hostile takeover bid by Ted Turner. In December 1985, CBS sold off most of HRW’s business to a German company and exited the consumer software business, taking a $7.5 million writedown on the latter. Felony! would end up being one of the final CBS Software releases.

HRW then reorganized the defunct CBS Software as CBS Interactive Learning, with a new focus on the growing market for software sales to schools (as opposed to homes). Selby Bateman wrote about this transition for the October 1986 issue of Compute! Gazette:

Previously known as CBS Software, the new Interactive Learning group has recently been concentrating more on sales to the education market than to home users.

[…]

While CBS has had a very large presence in the home computer market over the past several years, one of the most successful areas of the business has turned out to be the school market, says Marylyn Rosenblum, director of sales and marketing for CBS Interactive Leaning.

“Like lots of other people, we realized at some point that the consumer market wasn’t going to live up to the expectations or the investment we had made. But at the same time, we had, almost without knowing it, a small, profitable business selling some of our software to schools.”

“Because CBS is heavily involved in the educational market, it looked to people here like it would make sense to take what we had–a very valuable body of products–and focus on the area where we could realize a significant return. That’s what really started us turning toward the educational market.”

The first product from the new CBS Interactive Learning was The Novel Approach. This was a planned series of programs designed to help students read and understand famous novels. The first release focused on Lord of the Flies and was described in the August 1986 issue of Compute!:

Rather than replacing the reading of the book itself, the programs are meant to be used before, during, and after reading, Each includes three separate learning activities: The Discoverer, designed to pique interest before reading; The Explorer, a self-paced series of questions and answers that enhance understanding; and The Master, designed to test students’ knowledge of the story after it has been read.

There were at least four other announced Novel Approach programs. I don’t know how many, if any, made it to market. A few months after this report, in March 1987, Illinois-based video game company Mindscape, Inc., acquired HRW’s software assets, including CBS Interactive Learning, effectively putting an end to the division.

Former Teacher Launched Early “Courseware” Company

The company behind Murder, BrainBank, Inc., was the brainchild of Ruth Kaplan Landa. Landa was an elementary school teacher on Long Island in the 1960s and early 1970s. She later pursued a career in the financial industry and taught at the New School for Social Research in New York City. Landa would write in a 1983 book that she had no interest in computers until 1979, when she was talking to a friend working in microcomputers:

Inexplicably, I was strangely drawn to these slightly overgrown, intelligent typewriters hooked into television sets. I was thunderstruck with their potential as teaching devices. To my own disbelief, I became so preoccupied with creating education software I left a good job in the investment field and borrowed every dime I could get to produce courseware and put it on the market.

Landa incorporated Brain Box Inc. in December 1980. By 1982, she’d changed the name to BrainBank, Inc. BrainBank primarily developed educational lesson plan software under the name “Brainware” for use by teachers in the classroom. She also wrote her aforementioned book–Creating Courseware: A Beginner’s Guide–in 1984 to familiarize teachers with microcomputers and how to design lessons to take advantage of the technology.

Landa was, by her own admission, not a programmer. She hired other people to write the actual software. Charles Sanford Goldstein was the credited writer and programmer for both Murder and its follow-up Felony!

BrainBank never produced another commercial game after Felony!. BrainBank did self-publish some consumer titles early in its history. The most notable of these was probably the 1982 release Millionwaire, a multiplayer trivia game where players had to wager money and answer questions with the goal of reaching $1 million.

Based on some sources I reviewed, BrainBank ceased to be active concern sometime around 1986. But according to New York State corporation records, BrainBank, Inc., continued to exist until March 1993 when it was “dissolved by proclamation”–i.e., the company stopped filing its annual paperwork and was closed by the Secretary of State.

Ruth Landa went on to author a second book, a novel called Dad is a “Drinking Man”, published in 1999, and moved to North Carolina, where she taught computers at a local community college.

Notes from the Random Access File

- Computist was originally called Hardcore Computist, which may be the most awesome name ever used for a computer magazine outside of Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Tiny BASIC Calisthenics & Orthodontia.

- In 1984, when CBS Software was still active, the parent company entered into a joint venture with IBM and Sears Roebuck & Company to develop their own online service for home computer users. Initially dubbed “Trintex,” CBS dropped out of the project in late 1986, citing their ongoing financial struggles and a desire to focus on its core business (i.e., not computers). The Trintex project would eventually launch in 1988 under the name Prodigy.

- The Murder mechanic of having the computer refer you to numbered entries in a printed manual was also used in a 1988 game, Star Saga: One–Beyond the Boundary, and its 1989 sequel, Star Saga: Two–The Clathran Menace, both published by Masterplay. These were science fiction role-playing games where up to six players could participate. Unlike Murder, where all the clues were printed in a single book, Star Saga: One alone had 13 separate manuals containing all of the necessary text. (I owned this game as a kid; it was quite a departure from the normal Apple II fare.)