CCR Special 5 — Ken Uston's Professional Blackjack

In one of his earliest software reviews for the “Random Access” segment of Computer Chronicles, Paul Schindler praised Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack, noting that while “most computer games will just play blackjack with you,” this program “will teach you how to play the game and win using various point counting methods.” Schindler said it was also “pretty rare when the writer gets top billing when they name a computer program, but Uston deserves it.” Schindler explained Uston was a “former official of the Pacific Stock Exchange and now he’s a full-time gambler.”

So who exactly was Ken Uston? And how did he end up writing a computer blackjack game that originally retailed for $70?

From Anonymous Corporate Manager to the Face of Blackjack

Ken Uston did not actually become famous for winning at blackjack. At least, not in the sense that you might think of a modern professional gambler, like say someone who wins the main event at the World Series of Poker. Uston’s fame was largely self-created through a series of (mostly) unsuccessful lawsuits he filed in the late 1970s against casinos in Nevada and New Jersey that had banned him for card counting.

The legend of Ken Uston seems to begin in March 1974. At the time Uston was, as Schindler mentioned, working for the Pacific Stock Exchange in San Francisco. Specifically, Uston served as a senior vice president and CEO of one of the exchange’s subsidiaries.

As was frequently mentioned in accounts of Uston’s life, he graduated from Yale University as a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society and later earned an MBA from Harvard. Uston had been with the stock exchange since 1969 following stints at the Southern New England Telephone Company and American Cement Corporation. In short, Uston was basically just another unknown corporate middle manager. Prior to 1975, the only mentions of Uston that I could find in newspapers were references to his occasional side gigs as a jazz pianist.

So what happened in March 1974? As Uston later recounted in his first book, The Big Player, he received a call one day at work from a man named Al Francesco. For his part, Francesco said in a 2011 interview with Richard Munchkin that Uston called him first. Apparently, both men “were dating the same girl,” and Francesco said she told Uston to call him.

In any event, Francesco was a professional blackjack player. He’d assembled a “team” of players that used a card counting technique to improve their odds against the house. Essentially, most of the team members served as “counters” who placed minimum bets and kept track of the cards that were played. When the count reached a certain number of points, a spotter would signal a “big player” to come to the table and place large bets at better odds. As Francesco described his operation, “On any given trip there were 22 of us. We had three teams of seven–six counters and one [big player]–and myself as the 22nd person.” Francesco served as the “boss” of the group.

Uston had prior experience playing blackjack using a card counting system first developed by MIT professor Edward O. Thorp in the 1960s. Indeed, it was Thorp’s book on the subject that prompted Francesco to become a professional gambler himself. But by 1974, Francesco said he was using a newer “Advanced Point Count” system developed by a former casino pit boss, Lawrence Revere.

Francesco hired Uston to join the team. Eventually, Uston became one of the “big players,” all the time keeping his day job at the stock exchange. In his book, Uston claimed the Francesco team made a $520,000 profit between March 1974 and January 1975–and over a million dollars by mid-1976. But things came to a head in June 1976 when a pit boss at the Sands in Las Vegas figured out the scheme and barred Uston and his teammates from the premises.

The Legend of Ken Uston and His Many Lawsuits

The Sands incident is what really launched the legend of Ken Uston. He quit his job at the stock exchange and filed lawsuits against a number of Las Vegas casinos, accusing them of violating his civil rights by banning him from playing blackjack at their tables. Uston also published Big Player, which was co-written with journalist Roger Rapoport as a third-person narrative of Uston’s exploits with the Francesco team.

To the extent that this made Uston the “world’s most famous blackjack player,” it was largely by default. After all, most people involved in card counting don’t advertise that fact. Francesco himself told Richard Munchkin that he thought Uston “wanted to get caught” at the Sands that night because he’d already made a deal (without Francesco’s knowledge) to publish the book. Francesco alleged a representative of Uston’s publisher was present that night and that Uston “was putting on a big show for him.”

Uston’s lawsuits made national news. But they largely proved fruitless. For example, in March 1978 a federal judge in Nevada granted summary judgment to Hilton Hotels in a lawsuit Uston brought after he was barred from the Flamingo Hotel’s casino in June 1975. The judge said the casino’s decision to bar Uston was not “state action” for purposes of civil rights laws, and in any event there was no law protecting “better than average blackjack players” from discrimination.

The one case where Uston did manage to score a court victory was actually in New Jersey, not Nevada. In January 1979, Resorts International banned Uston from its Atlantic City casino. Prior to banning Uston, however, Resorts sought legal guidance from the chairman of the New Jersey Casino Control Commission. The chairman told Resorts that “no statute or regulation barred Resorts from excluding professional card counters from its casino.” After removing Uston, Resorts then adopted specific policies to identify and remove suspected card counters.

Uston initially challenged Resorts’ decision with the Commission, which sided with the casino. An intermediate appellate court later reversed the Commission, and that reversal was ultimately upheld in a May 1982 decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court’s decision was based on the specifics of New Jersey law. Basically, the law granted the Commission–not the casino–the sole authority to “exclude patrons based upon their strategies for playing licensed casino games.” In this case, Uston’s card counting did not violate any of the Commission’s rules for playing blackjack. (The Court declined to say whether the Commission could actually pass a rule banning card counters.) So Resorts had “no right to exclude Uston on [the] grounds that he successfully plays the game under existing rules.”

Uston’s overall lack of success in the courtroom did not dampen the media’s enthusiasm to tell his story. In June 1976, the Sunday New York Times Magazine published a lengthy profile of Uston written by Thomas Thompson. This profile made no mention of Uston’s role as part of Al Francesco’s team. To the contrary, Thompson portrayed Uston as a lone operator with “his system” of winning at blackjack.

A second profile, this one by Ray Hennedy for Sports Illustrated in April 1979, discussed Uston’s relationship with Keith Taft, a “self-taught computer engineer” who developed a “space-age microcomputer and battery pack” to facilitate Uston’s card-counting operation. This article also detailed how Uston (and a couple of dozen other people) were banned from Resorts in Atlantic City as part of what he dubbed “the Tuesday Night Massacre.”

The Intelligent Statements-Med Systems-Screenplay Triangle

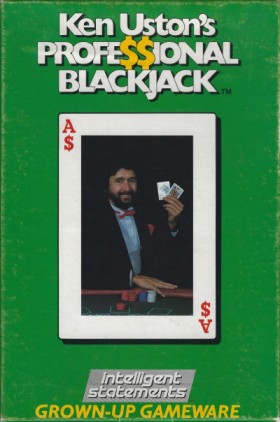

Two months after the New Jersey Supreme Court issued its ruling for Uston, a federal trademark was filed for Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack. According to records from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the name was first used in commerce on July 7, 1982, by Intelligent Statements, Inc., of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. As best I can tell, the original game was released around that time for the Apple II, with later ports to the Atari 8-bit computer line, the Commodore 64, and IBM PCs and compatibles running MS-DOS.

Now, when Paul Schindler reviewed the program sometime in 1984, he listed the publisher as “Screenplay.” This sent me on a whole wild goose chase trying to figure out the various software companies involved with Professional Blackjack. I still don’t have a completely clear picture, but here is my best guess based on the available information.

According to a January 1984 article in the Raleigh News and Observer, David Handel started Intelligent Statements, Inc. Handel was a radiologist at Duke University at the time. In 1981, Handel merged Intelligent Statements with another company, Med Systems Software, which was founded in 1979 by William F. Denman, Jr. Denman was a self-taught computer programmer working at North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill. He told the News and Observer that his first program for Med Systems was The BASIC Bartender, a computer database of mixed-drink recipes, which didn’t sell particularly well.

Med Systems actually had made a name for itself in the early 1980s as a developer and publisher of computer adventure games. The company’s Spring 1981 Catalog listed a number of games for the Tandy TRS-80 and Apple II computers, including Deathmaze 5000, Labyrinth, and Asylum, all of which were variants of dungeon crawlers. There were also some early titles that might charitably be described as “edutainment,” including The Human Adventure, a text-based game where players moved through a human body destroying cancer cells.

By 1983, the combined Intelligent Statements-Med Systems Software was now publishing titles under the “Screenplay” name. The January 1984 News and Observer article also said this combined company was now “under the umbrella of a parent firm, AGS Computers, Inc.” AGS was a publicly traded company based in New York. I reviewed a couple of AGS annual reports from this time period and could not find any reference to Screenplay. At some point, AGS apparently sold Screenplay to Sandy Schupper, who owned a couple of other small software companies at the time. On his LinkedIn page, Schupper said he was CEO of “Intelligent Statements/Screenplay” from 1980 to 1982. But that doesn’t fit with the timeline as I understand it. The News and Observer article was from January 1984, when AGS still owned Screenplay and it had recently named another person, Roger Shiffman, to serve as CEO.

Regardless of who actually owned the company, Denam was clearly the main person behind its software output. He told the News and Observer that Screenplay saw itself as a budding “leader in the industry,” which planned to be “up there with Broderbund, Spinnaker, and Sierra On-Line.” A few months later, News and Observer computer columnist James Calloway caught up with Denam at the 1984 Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, where Screenplay “had a 1,300-square-foot booth with break dancers”–the company planned to announce a breakdancing game, because this was the 1980s–as well as “an affiliation with Caesars Palace, to develop a line of gambling software,” effectively a follow-up to Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack.

I can’t find any definitive proof that Screenplay ever released a Caesars Palace-branded game. The earliest listing for such a title on MobyGames is a 1990 MS-DOS release published by Virgin Mastertronic International, Inc. By that point, Screenplay had long ceased publishing anything. In fact, I don’t think Screenplay continued as an active venture past 1985.

The only other clue I found with regard to the ultimate fate of Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack, at least with respect to the intellectual property rights, was an April 1988 filing with the U.S. Copyright Office. Blackjack and eight other software titles–none of them Screenplay programs–were listed as subject to a “loan and security agreement” by Telemarketing Resources and Venus Holdings, Ltd. Telemarketing Resources was the name of another company controlled at one point by Sandy Schupper. Again, I can only speculate, but perhaps the copyright to Blackjack and the other programs were used to secure a loan that Schupper took out.

Uston’s Later Career in the Computer Industry

There were two other video games that used Ken Uston’s name. The first was another gambling title, Ken Uston BlackJack/Poker for the ColecoVision, which came out in 1982. The ColecoVision release was not a port of Professional Blackjack, even though they came out around the same time. Coleco itself developed BlackJack/Poker, which was nothing more than simple video poker and blackjack games featuring an on-screen dealer who sort-of resembled Uston. (The dealer had dark hair and a mustache but not Uston’s trademark full beard.) Uston’s actual picture was also not featured on the box, as was the case with the Intelligent Statements/Screenplay releases.

The second game was Ken Uston’s Puzzle Panic–later just Puzzle Panic–published in 1984 by Epyx, Inc., and developed by Ken Uston’s own company, Fun and Games, Inc. As the title suggested, this was a puzzle game that had nothing to do with gambling.

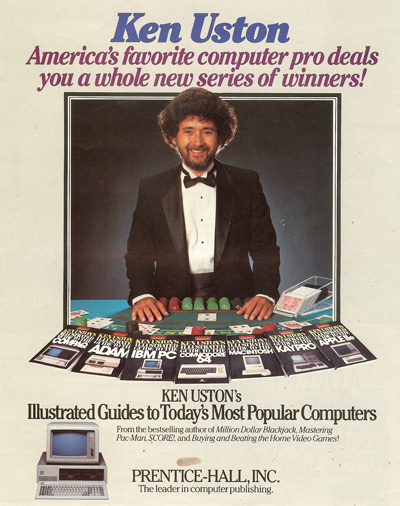

Uston’s Fun and Games, however, would prove to be a more proactive venture when it came to book publishing. To the extent that people outside the gambling world remember Ken Uston’s name today, it is probably as the author of a wide range of early video game and computer books, including illustrated guides to the Compaq, Adam, IBM PC, Commodore 64, Macintosh, Kaypro, and Apple II computers.

Uston’s public output seemed to have dropped off after 1984. On September 19, 1987, he was found dead, aged 52, in a Paris hotel room. The French authorities determined that Uston died of a heart attack and there was no foul play. According to a New York Times obituary, Uston had “spent the last year of his life on a computer project to help Kuwait track billions of dollars in investments.”

Marketing “Grown-Up Gameware” at Twice the Price

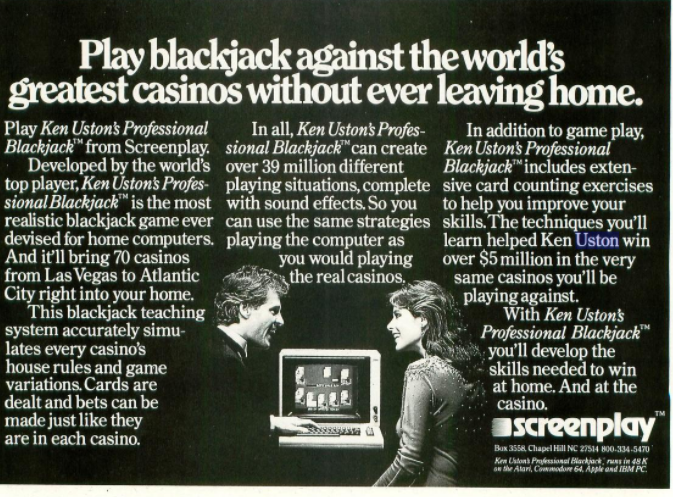

As for the game Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack, it’s actually quite an impressive feat for mid-1982. This was not just a video blackjack game, as Paul Schindler’s review noted. It was also a program that taught card counting techniques. The game referred to “Uston Advanced Point Count” method, which I’m guessing was just a slightly modified version of the Revere Advanced Point count system that Uston learned from Al Francesco back in 1974.

The other notable feature of Professional Blackjack was that it allowed the player to experience the game under the specific house rules of every major Las Vegas and Atlantic City casino of the day. This lends credence to the notion that Uston–by all accounts a very experienced gambler who knew the hotel-by-hotel rules intimately–himself programmed the original game. He is credited as the author, but in some of the media reports I mentioned above, Screenplay’s William Denman referred to “licensing” Uston’s name, which suggested it might have been developed in-house by Intelligent Statements/Screenplay. Of course, this could have also been a “John Madden Football” scenario where the Screenplay developers worked with Uston together in developing the final product.

I also wonder why the game cost $70. That was nearly double what the average computer game retailed for in this period. For instance, I saw Professional Blackjack reviewed in one 1984 computer magazine next to Richard Garriott’s Ultima and Broderbund’s Lode Runner, each of which retailed for $35. It was also a massive jump from the offerings I saw in the Med Systems Software catalog published in 1981, where most of the company’s adventure games cost less than $20 on disk.

No doubt that Screenplay had what it considered a “prestige” title on its hands, given both the affiliation with Ken Uston and the comprehensive scope of the program itself. And this was, obviously, a program marketed at adults rather than children. (The original Intelligent Statements box even called Professional Blackjack “Grown-Up Gameware.”) So presumably whoever owned Screenplay thought they could charge a premium price. I’d be curious to know how well the game actually sold, as my research turned up nothing on that front.

Notes from the Random Access File

- As far as I can tell, there’s no real differences in gameplay between the four computer versions of Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack. You can find all of them on the Internet Archive.

- Will Moczarski, who runs The Adventurers Guild blog, published a post in 2019 about Med Systems/Screenplay that has some additional background on the company’s work, specifically with adventure games. The CRPG Addict also interviewed Randall Don Masteller, who authored the game Warrior of Ras for Screenplay–and is also credited as the designer of a later Caesars Palace game.

- I found at least one Christmas 1983 retail ad for Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack, which had already been discounted to $56 from the original $70.

- As mentioned above, Uston also wrote video game strategy guides in the early 1980s, notably Mastering Pac-Man. Uston told Roger Dionne of Video Games, that it only took him four days to write the book, which he said sold 1.2 million copies.

- Some early ads for Professional Blackjack mentioned that additional ports of the game for CP/M-based machines and the Tandy TRS-80 would be available by Christmas 1982. Neither apparently came to fruition. The absence of a TRS-80 port is more notable given that Med Systems Software’s early catalog primarily targeted that system together with the Apple II.

- One of Uston’s lawyers during his many, many lawsuits was Oscar B. Goodman, who later served as mayor of Las Vegas from 1999 to 2011.

- The Roger Shiffman who was mentioned as a onetime CEO of Screenplay is not the same Roger Shiffman who was the co-founder of Tiger Electronics, Inc. Screenplay’s Shiffman previously headed Fox Video Games, Inc., which produced computer games in the early 1980s based on 20th Century Fox film and television properties.

- Regardless of system, Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack came on floppy disk–no cassettes!–and required 48 KB of memory. IBM PC and compatibles required an 80-column display. The game disks also had copy protection, which has long since been cracked.

- There is at least one other program in the “blackjack games licensed by famous card counters” genre–Edward O. Thorp’s Real Blackjack, named after the MIT professor and developed by Villa Crespo Software for MS-DOS computers in 1990.