Computer Chronicles Revisited 122 — FastBack Plus, Everex Excel Streaming Tape, PathMinder, Vopt, and Norton Disk Doctor

In 1980, Alan Shugart’s Seagate Technology shipped the first hard disk drive designed for microcomputers, a $1,500 unit that stored 5 MB of data. Roughly a dozen companies came out with their own hard disks over the next year. It was not until 1984, however, when IBM shipped the PC-AT with a 20 MB hard disk that the storage devices started to gain wider acceptance in the PC market.

By 1988, the typical business PC shipped with a 40 MB hard disk. If this doesn’t sound like much of an improvement over the 20 MB standard of four years earlier, it’s important to consider the limitations imposed by the operating systems of the time. The first release of MS-DOS (or PC-DOS) in 1981 had no support of any kind for hard disks. When DOS 2.0 released in March 1983, it could only support a single 10 MB hard disk. DOS 3.0, released in August 1984, made it possible to support multiple hard disks, but each was limited to a single 32 MB partition.

It wasn’t until the release of DOS 3.3 in April 1987 that you could effectively use a hard disk with more than 32 MB of storage. This was due to the introduction of “extended” partitions. For example, if you had a 128 MB hard disk, DOS could format it as one 32 MB “primary” partition and an “extended” partition with three “logical” drives of 32 MB each.

Shouldn’t DOS Already Do This?

As the hard disk capacity of DOS grew, so did the complexity of managing those drives–and its files–for the user. Many companies offered software and hardware add-ons to assist with hard disk management. That was the focus of this next Computer Chronicles episode.

Stewart Cheifet opened the program by asking Gary Kildall why a computer user would need additional programs to optimize, organize, or manage their hard disk. Why didn’t the operating system already do all this? Kildall said every user needed a good utility set to handle basic tasks such as archiving and backing up their hard disks. But then there were other utilities that looked at–and could alter–the underlying data structure of the disk. In inexperienced hands, this could lead to data corruption and other problems. So it made sense not to include such features in the base operating system. If a user then decided to buy a separate utility to do these things, then they assumed that risk.

DOS 4.0 Introduced New Shell

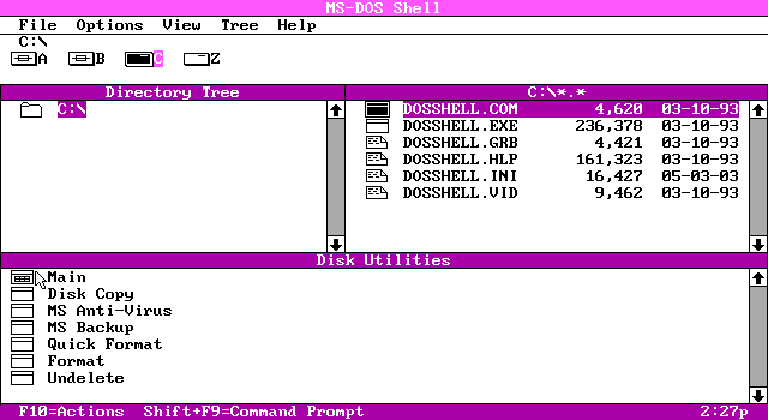

Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment from the headquarters of the computer retailer chain Businessland Inc. in San Jose, California. Woods said Businessland had been in business long enough to witness the evolution of the entire IBM PC and its operating system, from the first A:\ prompt to the latest DOS Shell. The company’s testing labs were filled with samples of new hardware and software, including the recently released DOS 4.0.

Jeff Edelstein, Businessland’s product evaluation manager, told Woods there were three main improvements in DOS 4.0 over DOS 3.3. The first was the break in support for larger partitions on a hard disk. In DOS 3.3, each partition was limited to 32 MB. Now, it was essentially unlimited. (Actually, it was 2 GB.) Second, there was now built-in support for the extended memory specification (EMS). Third, there was the introduction of DOS Shell (see below). This was a friendly interface wrapped around DOS to make it easier to use. This was important, Edelstein said, because people were starting to have more and more files on their hard drives.

Woods said the new DOS Shell, with its menu bars and windows, seemed tailor-made for a mouse, but it was meant to work with a keyboard as well. The colorful screen and extensive menus may also remind users of some other graphic interfaces. But DOS 4.0 was not an applications environment, even if it looked like one. Edelstein noted the DOS Shell was just the beginning of efforts to enhance the DOS environment. Long term, he thought IBM and Microsoft’s goal was to gravitate users towards the higher functionality of OS/2 and its Presentation Manager.

Indeed, DOS 4.0 had yet to prove itself acceptable among competing hard disk managers, Woods said. On the other hand, the dramatic change from a blank screen to one filled with information about files, directories, and the arcane DOS commands should make life easier for the everyday PC user.

Battle of the Backup Systems

Phil Grabmiller and Patrick O’Connor joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio for the next segment. Grabmiller was a regional sales manager with Fifth Generation Systems, Inc. O’Connor was an operations manager with Everex Systems, Inc.

Kildall opened by noting that one of the real problems with hard disks was that they were now very large–140 MB or more in some cases–which made it more difficult to backup all that data. As a result, many users simply don’t do backups. This was where a product like Fifth Generation’s Fastback Plus could help.

Kildall asked Grabmiller to explain Fastback Plus. Grabmiller said Fastback Plus used the existing drives in the systems to back up a hard disk to floppy disks. This provided a low-cost approach to performing backups. Kildall noted that required data compression. What was the actual compression ratio? Grabmiller said it was 3-to-1 for word processing and spreadsheet files, a bit less for bitmaps and other image files.

Kildall asked if Fastback Plus used standard file formats. Grabmiller said it did, which was a change from the older Fastback program. This meant the user could actually look at individual files when they examined a backup disk.

Kildall then asked about the average time it would take to backup, say, a 100 MB hard disk. Grabmiller said that would take roughly half an hour, depending on the amount of data compression and error checking. Kildall asked for an estimate of how many floppy disks that would take. Grabmiller wasn’t sure. Cheifet quipped, “A lot.”

Cheifet then asked for a demonstration of Fastback Plus. Grabmiller noted this was a redesigned user interface from the original Fastback (see below). There was now a built-in help feature. The user could highlight any menu item and hit F1 to bring up an explanation of what the feature did.

Grabmiller explained that when a user first ran Fastback Plus, they should perform a complete backup of their hard disk. Subsequently, the user could perform either an incremental or differential backup. An incremental backup was the difference between the current backup and the last one performed. A differential backup, in contrast, was the difference between the current backup and the original full backup.

Continuing his demo, Grabmiller simulated a backup. He showed how you could include or exclude individual files from the backup. You could also select the type of backup and the destination drive. The software could also tell you how many disks were necessary, as well as an estimate of how long it would take to perform the backup.

Cheifet asked about the best practices for using Fastback Plus. Grabmiller recommended using it at least once a day. If you were a casual user, you could get by with performing a backup once a week. But if you were in a business environment, a daily backup was more appropriate.

Cheifet next asked Grabmiller about the cost of Fastback Plus. Grabmiller said it was $189. Cheifet then wanted to know how many floppy disks would be needed for a typical hard disk backup (i.e., not 180 MB as Kildall suggested earlier.) Grabmiller said that for a 20 MB hard drive, it would take about one box of 3.5-inch floppy disks. (So about 10 disks.) Cheifet then asked how the use of data compression related to the speed of a backup. Grabmiller said the timing of the backup did slow down if you toggled data compression, but it was hard to estimate exactly.

Turning to O’Connor, Cheifet asked him to demonstrate his company’s product, the Everex Excel Streaming Tape system. O’Connor explained that Excel was an external 125 MB tape drive that came with a controller card and software. Kildall asked what the system cost. O’Connor said at retail it was about $1,800. (The tapes cost $40 each.)

Cheifet asked about the type of person who would use a tape-based backup system as opposed to something like Fastback Plus. O’Connor said tape systems were more commonly used in corporate and university environments where there were many power users.

Cheifet then asked for a demo. O’Connor performed a “quick” file backup using the Excel software. Kildall asked how long it would take to backup 100 MB of data. O’Connor said the tape system backed up about 5 MB per minute, so it would take about 20 minutes. And since it was a 125 MB system, a 100 MB backup would fit on a single cartridge. Kildall noted that like Fastback Plus, you could also select individual files or perform an incremental backup.

Cheifet wanted to know how the Excel system compared to something like the Bernoulli Box. O’Connor said the Bernoulli Box used removable media, which made it more of a disk-based backup system. The Excel was a cartridge-based system. He noted that Bernoulli Boxes were used in places like the banking industry, where the backup tapes could be removed and archived. The Excel, in contrast, was meant for networking environments.

Kildall asked if there were any industry standards used in the Excel. O’Connor said there were standards applicable to the controller card and how information was written to the cartridge. Basically, all of the actual backup tapes followed the same standards.

Cheifet wondered if newer, optical disc storage devices would made tape backups obsolete. O’Connor said he didn’t think so. He saw the tape-based storage eventually moving into the home, while higher-end optical storage backups would take over in the business market.

Protecting Your Hard Disk from Viruses

Wendy Woods returned for her second remote report, this time from the headquarters of Symantec, Inc., a California-based developer of Macintosh utility software. Woods noted that every Macintosh user’s worst fear was a floppy disk icon with a blinking question mark–a sign of a hard disk crash, which meant the operating system was gone. This was often the result of a computer virus, which could quickly wipe out a hard disk’s data directory.

To help prevent this outcome, the latest version of Symantec Utilities included an anti-virus program called Guardian. Woods said that if Guardian was installed before a virus struck, the program would stop the bug in its tracks. Karim Exmail, a product support manager with Symantec, told Woods that Guadian prompted the user if a virus program started overwriting a hard disk’s directory information. The user should then attempt to remove the virus program.

Woods said Symatec Utilities could also restore a hard disk following a crash, even if they were not previously installed on the system. Exmail noted there were two types of Mac users: people who have already crashed their hard disk, and people who were going to crash their hard disk. With Guardian, either group could recover their data.

With computer viruses in the news these days, Woods said, it was no surprise that programs like Symantec Utilities were selling well. In fact, Symantec said Utilities was the most popular program of its kind, with 10,000 units shipped each month.

Manage, Defrag, and Recover Your Disk

For the final segment, Frank Tantalo, Ted Knox, and Steve Koschmann joined Cheifet and Kildall back in the studio. Tantalo was president of Texas-based Westlake Data Corporation. Knox was a technical marketing manager with California-based Golden Bow Systems. And Koschmann was marketing director with California-based Peter Norton Computing, Inc.

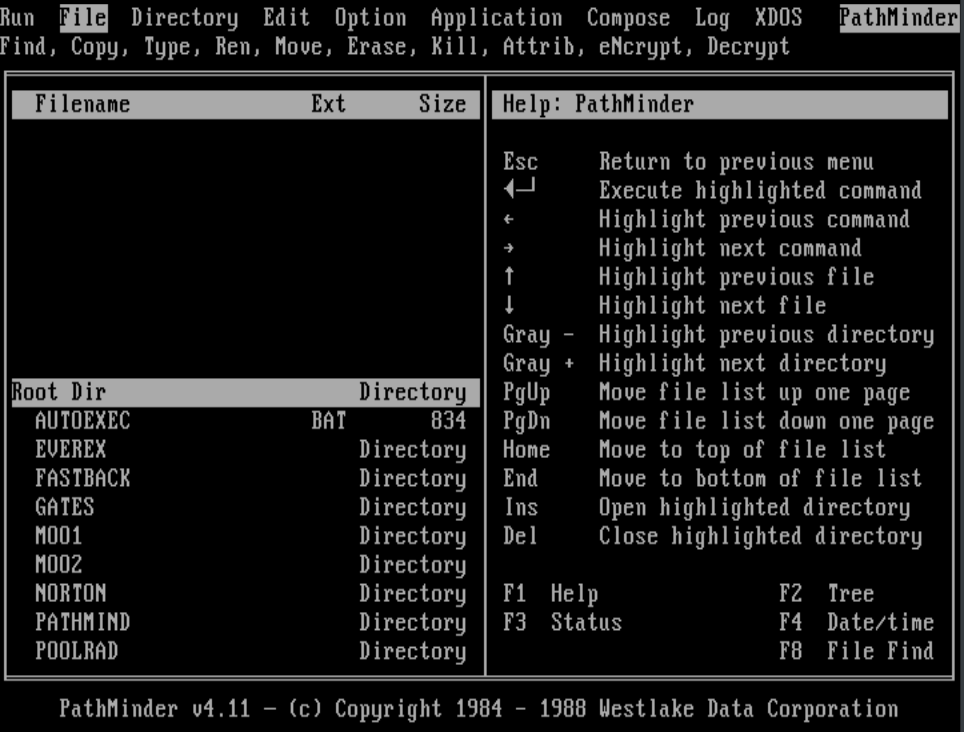

Kildall started with Tantalo, asking about his company’s product, PathMinder (see below). Tantalo said PathMinder was a shell for DOS to help users manage the large amounts of data on their hard disks. It included a file manager, directory manager, editor, and applications manager. To illustrate, he performed some basic file management tasks, such as creating a directory and copying a file, from within the PathMinder shell.

Cheifet asked if PathMinder was a substitute for typing DOS commands in manually. Tantalo said yes, PathMinder interfaced between the user and the machine. There was therefore no risk of typing or syntax errors.

Kildall noted the PathMinder user interface resembled that of Lotus 1-2-3. Was that intentional? Tantalo implicitly admitted that was the case, noting that he felt a Lotus-style menu bar was the easiest thing for a person to use. Cheifet clarified that when a user turned on their PC with PathMinder, the PathMinder shell would immediately appear. Tantalo said that was correct.

Next, Cheifet turned to Knox and asked about his company’s software, Vopt. Knox said Vopt was a hard disk de-fragmentation utility. He explained that with normal use, DOS took files and fragmented them throughout the hard disk. That is, when you copied, deleted, or updated an existing file, you tended to get fragmentation. Kildall asked why this was a problem. Knox said that since fragmented files were in separate locations on the hard disk, this contributed to excess wear and tear on the hardware. It also cost the user time. And once the files were continuous on the disk, it was faster for applications to access them.

Kildall asked for a demonstration of Vopt. Knox pulled up Vopt, which displayed a map of a hard disk drive in ASCII characters. He explained that the blue frames represented contiguous clusters. The yellow patches represented fragmentations. Knox then ran Vopt, which started by checking the disk for errors. Next, the program copied out the fragmented segments to the end of the disk one file at a time. Then Vopt restructured the files and moved them back to the front of the disk.

Cheifet asked if it was possible to quantify any performance improvement after running Vopt. Knox said the best test was to run the applications that took the longest, such as sorting a dBASE file or working with a spreadsheet, and timing the performance before and after using Vopt. The user should notice a difference. Knox added that he recommended running Vopt as a batch file every day.

Finally, Cheifet turned to Koschmann and asked about the newest release of The Norton Utilities (version 4.5). For his demo, Koschmann said he’d replicated a common problem faced by many users–you boot your computer up in the morning and nothing happens. That is, there’s been a hard disk crash. Koschmann noted that in the old days, a disk drive crash literally meant the head of the drive crashed into the magnetic media itself. That was no longer true in most cases. Instead, a “crash” often meant there was a corruption of the hard disk’s master boot record. For example, this could happen if there was a sudden power outage while the computer was in the middle of saving a file.

Koschmann replicated this by directly editing the master boot record in Norton Utilities so that the PC now could not boot from the hard disk. He then booted into DOS from a floppy disk. From there, he attempted to access the hard disk but received an Invalid drive specification error message. To correct this, Knox installed the Norton Utilities floppy disk and ran one of the included programs, Norton Disk Doctor.

Koschmann said Disk Doctor automatically diagnosed the problem with the hard drive. He noted that previously, if a user experienced a similar problem, they’d have to take their computer to a repair shop, which would use a hex disassembler to examine the master boot record. Disk Doctor, however, allowed the user to diagnose the problem on their own. In this case, the software could not detect a partition table on the hard disk, which meant there was no longer a master boot record. Disk Doctor therefore rebuilt the master boot record and “revived” the various partitions on the disk. After the program completed, Koschmann was able to reboot into DOS from the hard disk.

Finally, Koschmann said that Norton Disk Doctor diagnosed many common disk problems in addition to master boot record corruption. It could also diagnose, report, and fix file application table errors such as lost clusters.

The DOS 4.0 Debacle

When Stewart Cheifet introduced Wendy Woods’ report on the new DOS release, he called it “MS-DOS 4.0.” Indeed, that’s what Woods herself called it in a July 26, 1988, NewsBytes article. But Woods also noted:

Analysts say IBM did most of the work on the new DOS and licensed it back to Microsoft, both out of respect for the software company’s previous work on DOS, and out of concern that the public not perceive IBM as abandoning its newer operating system, OS/2.

Now, IBM had always released its own, slightly different version of DOS for its own PCs under the name “PC-DOS” since the original IBM PC shipped back in 1981. This initial July 1988 release, however, was called “IBM DOS 4.0.” Microsoft held back on shipping MS-DOS 4.0 until September 1988. (To add further confusion, there was also a “Multitasking MS-DOS 4.0” under development that Microsoft never officially released.) Keep in mind, DOS was not considered a retail product at this time; Microsoft shipped its version of DOS directly to PC clone-makers.

Development of DOS 4.0 largely flew under the radar as IBM and Microsoft–well, mostly IBM–continued to push OS/2 as the operating system of the future. But as Brit Hume and T.R. Reid wrote in their syndicated column in August 1988, “The introduction of a major revision of the old operating system makes it clear that IBM and [Microsoft] both recognize [] the commercial shortcomings of OS/2, the overpriced and (so far, at least) underpowered operating system that is supposed to release MS-DOS.”

At the same time, Hume and Reid wondered how many users would actually take advantage of the new DOS Shell in DOS 4.0 given that there were already a number of popular third-party DOS shell programs in wide use (such as PathMinder.)

Of course, that assumed existing third-party programs would even work correctly under DOS 4.0. Frank Ruiz of the Tampa Tribune noted in a September 1988 review that he “immediately had trouble” running Borland Sidekick, a terminate-and-stay-resident personal information manager program, in IBM DOS 4.0 due to a known bug. For that matter, Ruiz found DOS 4.0 didn’t even run on certain PC compatibles, such as an Epson portable computer. Ultimately, Ruiz concluded these “quirks tend to override the benefits” promised by DOS 4.0.

Another stumbling block, which turned out to be a “feature” rather than a bug, was IBM’s decision to introduce copy protection for the first time into DOS. Wendy Woods reported:

[T]he new DOS can’t be copied to a hard disk or to other than the original media type. If it is, the installation process required to create the new DOS Shell, the product’s major innovation, will fail to work from the new media.

The copy protection employs a hidden directory entry and other strategies that allow the user to use the

DISKCOPYcommand to reproduce backups but not to copy the installation files to a different media format withCOPYorXCOPY. Furthermore, at least some earlier versions of DOS will notDISKCOPYthe new format. And, users with compatible machines may find that their system will not start from the installation diskette in any case.

Woods added that few people seemed to notice the copy protection, however, given the many other problems with the initial IBM DOS 4.0 release. These mounting bugs were what pushed back Microsoft’s release of MS-DOS 4.0 to clone-makers until September 1988. This was then followed by another Microsoft-led revision–MS-DOS 4.01–which came out in April 1989.

It was clear to most industry observers by that point, however, that DOS 4.0 was a dud. Patrick Waurzyniak, writing for Comptuerworld in April 1989, said, “Microsoft users appear reluctant to migrate their applications to” the new release. Even the 4.01 revision was still buggy, including what Waurzyniak described as a potentially catastrophic issue with the operating system’s hard disk partition management:

The latest bug, although admittedly a minor one that would occur only during a sequence of obscure commands and with storage partitions of more than 32 MB, can potentially cause a ‘significant’ loss of data, although no users have thus far lost data, Microsoft said.

Echoing Hume and Reid’s warning from the previous year, there was also increasing pushback from leading clone vendors, such as Compaq, whose users simply didn’t want DOS Shell or any similar attempt to impose a new interface. “A lot of our large accounts have said they have written their own interface for the DOS 3.3 level,” Compaq’s Lorie Strong told Computerworld. “So they’re not anxious to introduce another user interface.”

It’s also worth noting that it was possible to create multiple 32 MB “logical” partitions on DOS 3.3 thanks to Compaq, which added the feature to its own version of DOS back in November 1987. This version, known as DOS 3.31, was later shipped by Microsoft to other clone-makers.

Ultimately, the majority of PC users stuck with DOS 3.3 or older versions. Microsoft waited nearly three years until releasing MS-DOS 5.0 in June 1991. This would be the first version of DOS sold directly to consumers at retail, as well as the last DOS jointly developed with IBM.

As a postscript, in April 2024, Microsoft released the original IBM DOS 4.0 source code under an open source license.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was first broadcast during the week of December 20, 1988. The studio portions were recorded on November 5, 1988. The Acrhive’s recording is a rerun from the week of May 25, 1989.

- Founded in 1982, the 57-store Businessland chain had a strong 1988, reporting a 90 percent increase in profits on $232 million in sales to start the year, launching a mail order business, acquiring rival computer retail chain Computercraft, and announcing plans to go public. Unfortunately, things started to come apart in 1989. In February, Compaq ended its longstanding distribution agreement with Businessland. Attempting to rebound, Businessland signed a distribution deal with Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computer. As Luke Dormehl discussed in a 2024 Cult of Mac post, that proved disastrous, as Businessland only sold 360 of the $10,000 machines. The Businessland-NeXT deal ended in May 1991, and shortly thereafter JWP Inc., acquired Businessland for $54 million and an assumption of the company’s substantial debts.

- Jeff Edelstein jumped off the sinking Businessland ship in 1991, resurfacing as a marketing manager at Samsung in 1994 and later doing stints at Sony Electronics and Philips Consumer Electronics before going out on his own as a consultant in 2002.

- Phil Grabmiller was a sales manager for Quadram Corporation before moving to Fifth Generation Systems in 1987. He left the company in 1989 and spent the next 30 years working in sales for a number of tech companies, including Epson, Microsoft, and Hitachi Vantara, retiring from the latter in 2020.

- Steve Koschmann was a product manager for Nabisco, overseeing marketing for Carefree Sugarless Gum, before working at a number of tech companies, including Peter Norton Computing, where he was named director of marketing not long before this episode aired. In 1996, Koschmann started his own company, Colorado-based Fluid Forms, Inc., which developed orthopedic and professional knee pads. Koschmann told BizWest in 2003 his inspiration came from a tile mechanic who “expressed an immediate need for a kneepad that would allow him to get back to work pain free after his second knee surgery.” Koschmann served as Fluid Forms’ president until the company dissolved in 2014.

- Symantec, Inc., acquired two of the other companies featured in this episode: Peter Norton Computing, Inc., in May 1990; and Fifth Generation Systems, Inc., in September 1993. Founded in 1985, Louisiana-based Fifth Generation built its reputation on the Fastback line of floppy disk-based backup software. But according to a 2020 report in Forbes, the Symantec acquisition had more to do with Fifth Generation’s interest in an Israeli anti-virus software company, which helped further Symantec’s transition from selling general system utilities to security (and later cybersecurity) products. After the acquisition, Symantec absorbed Fifth Generation into its Peter Norton Computing Group.

- Founded in 1983 by Steve Hui and John Lee, Everex Systems, Inc., was primarily a builder of IBM PC clones, although it also saw success selling hard disk drives and tape-based backup systems. At one point, Everex reportedly had a roughly 50 percent share of the global tape-backup market. Unfortunately, the PC price wars of the early 1990s largely decimated Everex’s PC sales and forced the company to lay off more than half of its staff. In January 1993, Everex filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. That November, the Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group acquired Everex for a reported $2.2 million. Under Formosa’s ownership, Everex reinvented itself as a manufacturer of low-cost PC notebooks. In September 2008, NewMarket Technology, Inc., acquired Everex from Formosa.

- Austin, Texas-based Westlake Data Corporation existed from 1984 to 1996. Designed by Albert Nurick and Brittain Fraley, PathMinder was Westlake’s first and apparently most successful product.

- Howard Barry Emerson and Elizabeth G. Bryson founded Golden Bow Systems in 1984. Emerson also developed Vopt, which he continued to update and release for Microsoft Windows up until his death in February 2016. In his will, Emerson released Vopt 9 as freeware.

- Westlake Data Corporation’s Frank Tantalo was really pissed off about software “pirates” illegally distributing PathMinder. He once offered a $2,000 reward to “any individual who provides information leading to the apprehension and indictment of persons responsible for placing PathMinder or any other Westlake Data product on a computer bulletin board.”