Computer Chronicles Revisited 120 — Home Video Producer, Ad Lib Music Synthesizer Card, AmandaStories, Crystal Quest, and Shufflepuck Café

Gregg Keizer, the editor of Compute! magazine, lamented in his editorial note for the December 1988 issue that, “There are not that many of us” who owned personal computers. He noted that “recent estimates tell us that no more than 20 percent of American households have a personal computer,” which was “not anywhere near the level of, say, VCRs.” Keizer imagined a world where computer software stores were as ubiquitous as video rental shops.

Indeed, the theme of that holiday season issue of Compute! was “Sights and Sounds,” with a cover story on using your home computer to “create Hollywood home videos.” While we were still a couple of decades away from people creating entire feature films on an iPhone, even the humble Apple II could be useful in adding titles and other audiovisual effects to a videotape that played in a VCR. In this sense, tying the personal computer to the VCR was a transitional step towards the idea of the “multimedia PC,” which became the focus of the industry’s marketing during the early 1990s.

The Computer Chronicles gang seemed to be thinking along similar lines when they gathered round the big wooden desk in San Mateo for their 1988 holiday buyer’s guide episode. In contrast to last year’s holiday show, there were no creepy talking robot toys to be seen. Instead, the focus was on exciting new audio-visual products for the IBM PC and Mac platforms. And while none the items recommended by the show’s hosts and regular contributors proved as commercially successful as the best-selling toy of 1988–the Koosh Ball–we still get a good idea of where the computer industry was headed from many of this year’s featured selections.

Asking Santa for an “Electronic Book”

Stewart Cheifet kicked things off by showing Gary Kildall the new Compaq SLT/286 laptop. It ran off a removable battery pack that lasted up to 3 hours and featured a monochrome VGA display and a detachable keyboard. Cheifet emphasized it was very small for a laptop–it only weighed 14 pounds (6.35 kg) and could actually fit on your lap, even when sitting on a coach seat in an airplane. The only catch was that you practically had to be Santa Claus to afford it at $6,000. (This was for a model with a 40 MB hard disk; Compaq also sold a 20 MB model for the bargain price of $5,400.)

Cheifet then asked Kildall what his ideal Christmas gift from the computer industry would be. Kildall said he was still waiting for the Dynabook. This was a concept introduced by Xerox PARC in the 1970s for a compact “electronic book” form factor for a personal computer. Kildall said that many technologies–notably smaller disk and CD-ROM drives–were coming together such that a real Dynabook should be possible in the near future.

Software Still a Hot Christmas Gift

Before getting to the main portion of the program, Wendy Woods made her annual pilgrimage to a local computer retailer to see how things were shaping up for the holiday sales rush. This year, Woods visited Friendly Computer Store in San Carlos, California. Woods noted that during this time, computer hardware and software vendors were just like other retailers who counted on Christmas shoppers to round out the year’s sales. New technology displaced the old, while old favorites like flight simulators and adventure games remained solidly popular.

While it had been more than 10 years since the first Apple II computers hit the market, Woods said that retailers hadn’t seen a slowdown in consumer buying when it came to computers. Al Thoman, the owner and president of Friendly Computer Store, told Woods that he was always scared to death of the market being saturated, but that didn’t appear to be the case this year. People were still buying basic PCs even though the manufacturers had abandoned such older models. Many users were also now upgrading from their original PCs to newer, Intel 386-based machines.

Woods said that among the new items on sale this year was a database of city street maps called Streets. People traveling by car could use Streets to plan their route from Point A to Point B through major American cities, although Woods quipped the program would not predict accidents or breakdowns.

Another new program was a game for “almost” grown-ups called Leisure Suit Larry Goes Looking for Love (in Several Wrong Places), an adventure game featuring a clumsy-but-determined young rogue named Larry. Woods added that players could choose different levels of play, from “pure innocence” to “lurid excess.”

For the information hungry, Woods said there was Microsoft Bookshelf, a CD-ROM collection of reference works. Starting from a single word, Bookshelf searched through its encyclopedia, almanac, and dictionary until it hit upon the exact link. Of course, you actually needed a CD-ROM player to use Bookshelf.

Using the PC to Improve Your Home Movies

Paul Schindler, then with PC Week magazine, and Jan Lewis of Lewis Research Corporation joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first round of holiday gift suggestions. Schindler went first, noting that colleague Richard Dalton assisted him with these selections:

-

Ken Skier’s No-Squint (SkiSoft, Inc., $40), a laptop utility that turned the standard “line” cursor into a square, making it easier to see on laptop screens. Schindler added that No-Squint only required 1 KB of memory. (I discussed the history of Ken Skier and his company in my post on last year’s holiday episode.)

-

The VDS 240 (Vertical Solutions, Inc., $40), a wall-mounted plastic storage unit for up to 240 3.5-inch floppy disks.

-

Instant Ventura Publisher: 22 ready-to-run style sheets for instant productivity by Tony Pompili, Kate Hatsy Thompson, and Steven J. Bennett (Brady, $40), a guide (with floppy disk) to the PC desktop publishing program Ventura Publisher.

-

OPTune (Gazelle Systems, $99.95), a disk management utility.

-

Groupware: Computer Support for Business Teams by Robert Johansen (Free Press, $30), a book about “groupware,” which Schindler said was one of the “hot buzzwords” of 1988.

-

The Norton Utilities 4.5 (Peter Norton Computing, Inc., $110), which included what Schindler described as “artificial intelligence-assisted disk repair.”

-

The JT Fax (Quadram Corporation, $500), a portable fax card that attached to the COM port of a PC. Schindler added this made it possible to “move” the fax from user to user in an office as needed. (Computer Chronicles previously covered the JT Fax in a May 1988 episode featuring Quadram general manager Jan L. Ozer.)

Gary Kildall went next. His first recommendation–as befitting a man who owned a Lamborghini–was Grand Prix Circuit (Accolade, $30), a Formula 1 racing game for the PC. Kildall noted his 12-year-old son was a big fan of the game.

Kildall then demonstrated his next recommendation, Home Video Producer (Epyx, Inc., $49.95), a program that allowed you to make titles for your own home video recordings. Schindler noted that when he needed video titles done, he went to a studio that charged $30 per hour, while this program only required a one-time payment.

For his demo, Kildall applied video titles to a stop-motion animation short created by his daughter Kristin called “Pokey Meets Godzilla.” (Pokey was the horse from the Gumby cartoon series.) Lewis clarified that the video and titles were output directly from the PC. Kildall said yes, adding the titles were generated though the PC’s CGA card.

Turning to Lewis, she recommended Traveling Software’s Battery Watch ($39)–the subject of a May 1988 episode–as well as the company’s Laptop Attache Bag ($79). She also recommended the Intel Inboard 386/PC ($1,000), a 386 upgrade board for older PCs, which was previously demonstrated in yet another May 1988 episode.

Cheifet then presented his selections, starting with Do-Color (Wilkinson Software, Inc., $30), a program that made it possible to run applications requiring a CGA card on monochrome displays. Next, Cheifet showed off a $150 60-percent size keyboard compatible with PC-XT and AT systems. Then he moved to his main demo for the segment, the Ad Lib Music Synthesizer (Ad Lib, Inc., $245), an expansion card and software package that generated music on a PC. Cheifet pulled up the Ad Lib’s bundled Juke Box applications, which played individual musical tracks, before showing you could create music using another built-in program called Visual Composer.

Finally, Cheifet pulled out a giant paper map of the CompuServe online service, which retailed for $3.95.

The Best in Mac Gaming

Wendy Woods joined the assembled group for the final segment, which looked at gifts for the Mac user. Jan Lewis, who edited the short-lived HyperCard-focused HyperAge magazine during 1988, began by showing Mac Recorder (Farallon Software, $199), a hardware device used to record and digitize audio for the Mac.

Lewis next recommended two HyperCard-based products: HyperAnimator and AmandaStories. HyperAnimator (Bright Star Technologies, $150) took still images of a person and applied digitized speech to create the very-rough illusion of an animated talking head. Schindler compared the effect to Max Headroom. (Cheifet noted he previously used HyperAnimator to create his cold open for the recent episode covering the Boston MacWorld Expo.)

AmandaStories was a series of HyperCard-based interactive storybooks for children. Lewis demonstrated one of the stories, Your Faithful Camel Goes to the North Pole (see below). By clicking on different spots, Lewis explained, you could take the story down diverging paths.

Next, Wendy Woods recommended three gifts. The first, Gofer (Microlytics, $80), was a text-searching accessory for the Macintosh. Woods said it could search through any word processing or ASCII text file. Both Lewis and Cheifet added they used Gofer regularly. (Paul Schindler also previously reviewed Gofer in a January 1988 episode.)

Woods’ second recommendation was The Macintosh Bible, Second Edition, edited by Arthur Naiman (Goldstein & Blair, $28). Finally, she recommended a computer novelty gift, The Chocolate Byte (The Chocolate Software Company, $13.95), a set of two 3.5-inch floppy disks made entirely of milk chocolate. Schindler noted that last year, these were 5.25-inch chocolate floppy disks.

Speaking of Schindler, he demonstrated his final recommended gift, Crystal Quest (Casady & Greene, $50), which he called one of the most interesting and addictive games available for the Mac, noting his seven-year-old daughter was “absolutely mad” about it. Schindler briefly played the game for the demo, explaining that it used mouse controls.

Kildall then recommended another HyperCard-based game, The Manhole (Mediagenic/Activision, $50), and the Maxx (Alturas Corporation, $99.95), a control yoke designed for PC flight simulator games. (Cheifet previously showed off the Maxx in a cold open to an April 1988 episode.)

Cheifet then closed out the program with three recommended products. The first was another laptop, the NEC UltraLite ($2,999), a four-pound MS-DOS PC with no disk drive but instead relied on 2 MB of battery-backed static RAM for storage. The second was Starting Lineup Talking Baseball (Parker Brothers, $89.99), a two-player electronic baseball game shaped like a stadium that used speech synthesis to provide “play by play” commentary (see below). The players used cartridges to play as different real-life baseball teams and players.

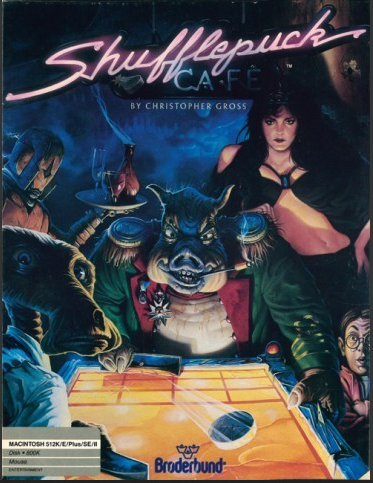

Finally, Cheifet demonstrated Shufflepuck Café (Broderbund Software, Inc., $39.95), a single-player mouse-driven air hockey game for the Mac where the player could choose from among a number of unique computer opponents.

Ad Lib’s Brief Moment

Stewart Cheifet’s demonstration of the Ad Lib Music Synthesizer was significant in that it likely helped introduce the idea of a PC sound card to a national audience. The original IBM PC relied solely on an internal speaker that produced beeps to generate sound. It was not a “synthesizer” in any sense, as the beeps relied solely on a timing chip sending electrical signals to the beeper. It was possible, however, to produce rough digital music through careful manipulation of that timing.

Of course, by the late 1980s there were many personal computers that came with built-in sound chips capable of FM synthesis, such as the Commodore 64, the Atari 520ST, and the Apple IIgs. This made sense as these were all machines heavily used for gaming, whereas sound cards were generally not a priority for business-focused PC users and application developers.

In 1987, Quebec-based Ad Lib, Inc., released its Ad Lib Music Synthesizer Card for the IBM PC. The Ad Lib was built on a Yamaha YM-3812 FM Operator Type-L II programmable sound generator, more commonly referred to as the OPL2. The blog Nerdly Pleasures explained in a 2015 post that Ad Lib’s card “was made entirely from off the shelf parts and a pair of specialized sound integrated circuits.” Ad Lib went so far as to scratch the part numbers off of the Yamaha chips in an attempt to maintain the secrecy of its design.

Ad Lib initially marketed its Synthesizer Card as a “music creation device” rather than an accessory to generate music or sound effects for other applications. That’s why Ad Lib initially sold the Synthesizer Card, which came bundled with the Visual Composer software that Stewart Cheifet demonstrated, for $245. At that price, the Ad Lib “did not instantly set the PC world alight and inspire software developers with new visions of affordable music,” according to Nerdly Pleasures. But that would change when one of the most successful developers of PC game software decided to throw its weight behind the Ad Lib.

That developer was Sierra On-Line. Wendy Woods referenced a Sierra game during her remote segment–Leisure Suit Larry Goes Looking for Love (in Several Wrong Places)–but it was another of the company’s 1988 releases, King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella, which became synonymous with the Ad Lib card.

Jimmy Maher of The Digital Antiquarian detailed the origins for Sierra’s relationship with Ad Lib in a 2016 post on the creation of King’s Quest IV. As Maher explained, Sierra co-founder and CEO Ken Williams had always been bullish on the IBM platform for gaming, and with the company recently developing a new engine for its signature adventure games, “King’s Quest IV was always planned as the real showcase for Sierra’s evolving technology, the game for which they would really pull out all the stops.” This included doing something seemingly unprecedented for PC games of the time:

[Williams] decided he’d like to have a real, Hollywood-style soundtrack in this latest King’s Quest, something to emphasize Sierra’s increasingly cinematic approach to adventure gaming in general. Further, he’d love it if said soundtrack could be written by a real Hollywood composer. Never reluctant to liaison with Tinseltown — Sierra had eagerly jumped into relationships with the likes of Jim Henson and Disney during their first heyday years before — he pulled out his old Rolodex and started dialing agents. Most never bothered to return his calls, but at last one of them arranged a meeting with William Goldstein. A former Motown producer, a Grammy-nominated composer for a number of films, and an Emmy-nominated former musical director for the television series Fame, Goldstein also nurtured an interest in electronic music, having worked on several albums of same. He found the idea of writing music for a computer game immediately intriguing. He and Ken agreed that what they wanted for King’s Quest IV was not merely a few themes to loop in the background but a full-fledged musical score, arguably the first such ever to be written for a computer game.

Goldstein balked at the notion of writing his musical score for the traditional PC beeper-speaker, so he suggested targeting the Roland MT-32, an external synthesizer module that plugged into the PC. Williams agreed, despite the fact the MT-32, which retailed at its 1987 launch at $695, was a cost-prohibitive add-on for most home computer users.

When Ad Lib launched its own $245 Synthesizer Card not long after Roland, however, that gave Williams another option. While Maher noted the Ad Lib “left much to be desired in comparison to the MT-32,” it was still “worlds better than a simple beeper.” So Williams added Ad Lib support to all of Sierra’s new adventure game releases going forward. Sierra also sold the Ad Lib card through its own catalog to help spur user adoption.

Ad Lib, Inc., seeing where the market was now headed, developed a revised version of the Synthesizer Card in 1990, now with new packaging that, as Nerdly Pleasures pointed out, emphasized its use in making “PC games come alive” as opposed to the original box’s emphasis on music creation. Indeed, the 1990 Ad Lib did not include the Visual Composer software and retailed at a lower price of $195.

By this point, however, Ad Lib’s success had already attracted initiators. Nerdly Pleasures explained that since Ad Lib used off-the-shelf parts and “released programming information giving the abilities and register specifications for the chips,” it didn’t take long for clone-makers to figure out the key chips came from Yamaha, which was not under any sort of dealer exclusivity with Ad Lib. The most notable clone came from Singapore-based Creative Technology PTE Ltd. At the fall 1989 COMDEX show in Las Vegas, Creative announced the “Sound Blaster,” an Ad Lib-compatible PC synthesizer card.

The Sound Blaster quickly took off and became the de facto PC sound card standard for the remainder of the MS-DOS era. Meanwhile, Ad Lib, Inc., struggled to keep up. In 1991, Ad Lib announced plans to release two next-generation sound cards, the Ad Lib Gold 1000 and Gold 2000. But the company struggled to actually get the new cards out the door. In June 1992, Wendy Woods’ NewsBytes reviewed “a beta version of the Gold 1000” and did not have positive things to say:

[T]he card was extremely buggy and trouble prone. The hardware card seemed to work well enough, but the software was riddled with bugs, such as the install program wasn’t smart enough to install a 3.5-inch disk designated as the B: drive and it wouldn’t work with Microsoft Windows 3.1.

On May 1, 1992, Ad Lib closed its doors and filed for bankruptcy. An Ad Lib spokesman initially told NewsBytes the company “had been purchased by a consortium of Canadian companies.” But that deal fell through and the Quebec provincial government took possession of Ad Lib directly for several weeks before selling its assets to a German holding company, Binnenalster GmbH. In August 1992, Binnenalster reopened the company as AdLib Multimedia Inc., which finished production of the Gold-series sound cards.

Binnenalster apparently sold AdLib Multimedia to a Taiwan-based company in 1995. As best I can tell, AdLib continued to operate until around 2000.

The Year of the Mouse

The Macintosh games recommended (and sort-of demonstrated) by the hosts in this episode are instructive largely because they represented early examples of mouse-based controls in computer gaming. Apple didn’t invent the mouse, but it introduced the input device to a wider audience of users with the Macintosh. And while Apple executives of the time–notably product head Jean-Louis Gassée–were famously hostile towards using the Mac as gaming platform, that didn’t stop up-and-coming game developers from seeing what could be done with the single-button mouse.

Goodenough to Inspire Myst

Combined with HyperCard, the mouse provided a fairly straightforward point-and-click interface that just about anyone could use to make a simple game. That was the case with the AmandaStories series, named for its developer, Amanda Goodenough. She wasn’t a game developer or programmer prior to creating AmandaStories. Indeed, as Jimmy Maher explained in a 2021 Digital Antiquarian post, Goodenough was married to a marriage counselor in 1987, and one of his clients was Bill Atkinson, the Apple developer who created HyperCard. According to Maher, “When [Goodenough’s husband] brought home a pre-release version of HyperCard, courtesy of his client, his wife started to use it to chronicle the adventures of her little black cat Inigo in the form of an interactive picture book.”

A few months later, at the HyperCard-fueled MacWorld Expo/San Francisco 1988, Goodenough met Bob Stein, whose Voyager Company developed a HyperCard-based interactive video guide to the National Gallery of Art. Per Maher, Stein and Goodenough “inked a deal to release her first four stories on floppy disk under the Voyager imprint.” This was followed by a second collection featuring the Your Faithful Camel Goes to the North Pole story that Jan Lewis demonstrated. (Goodenough also contributed some of her art to the second issue of Lewis’ HyperAge magazine.)

It’s not clear how well the two AmandaStories collections sold, but according to Maher, Goodenough’s work proved a critical influence on another HyperCard-based product briefly mentioned by Gary Kildall in this episode: The Manhole. The creators of that program, brothers Robyn and Rand Miller, went on to develop the landmark Myst series through their still-active company Cyan, Inc.

Goodenough herself never developed any games or software after AmandaStories. Indeed, Her only other notable credit in the industry was as the art director for Balance of the Planet, a 1990 Macintosh political simulator created by somewhat pretentious developer Chris Crawford. Crawford later recalled in a 2003 book that he was “dissatisfied with the ultra-realist style so common in computer games” and chose Goodenough to create artwork for Balance because her “clean, sweet style was just I wanted.”

Buckland’s Quest Results in Carmageddon

Crystal Quest, the Mac game that enthralled Paul Schindler and his young daughter, had something of an unusual origin story. The developer, Patrick Buckland, was based in the United Kingdom. A native of the Isle of Mann, Buckland was the rare Apple loyalist in a land dominated by the likes of Commodore, Sinclair, and Amstrad.

Buckland himself first learned to program on a Commodore VIC-20 at school. His introduction to Apple came when his grandmother bought him an Apple II in 1979. As Richard Moss detailed in his 2021 book, The Secret History of Mac Gaming, Buckland spent his first two years with the Apple II developing a commercial game he called Liberator. A publishing deal fell through, however, when Atari, Inc., objected to the Liberator name on trademark grounds, as it conflicted with the name of one of Atari’s coin-operated arcade games.

After that, Buckland became a freelance programmer, which included doing quite a bit of contract work for Apple’s UK division. This connection enabled him to get a hold of the Lisa and later the Macintosh when those machines launched.

This led Buckland to develop a mouse-based, clear-the-screen game called Crystal Raider, which he programmed in just two days. Having been burned by his publisher on Liberator, Buckland opted to distribute Crystal Raider as shareware, inviting users to send him $10 if they liked the game. Moss explained how this almost proved to be more trouble that it was worth:

[Buckland] got around 350 cheques to register Crystal Raider over the course of a year. Most came from the United States, which hosted almost the entire Mac market. This was a problem. The standard cost of processing an international cheque in the UK was about the equivalent of $10 – the same as his nominated shareware fee. In order to get any money out of the transactions, he’d hoard the cheques until he had about fifty of them and then do a bulk deal with his bank manager. That way he received around $6 per US sale.

Another problem created by Buckland’s shareware approach was that he promised to send his next game–Crystal Quest–to everyone who paid the $10 to register Crystal Raider. But at this point, Crystal Quest was vaporware. Buckland later recalled to Moss that he had “absolutely no idea” what Crystal Quest would even be as a game. He started working on a concept for a shoot-’em-up game but quickly abandoned that idea. Another year passed before Buckland decided to resurrect Crystal Quest as a straight-up sequel to Crystal Raider, albeit a “more polished, feature-rich version,” according to Moss.

During the development process for Crystal Quest, Apple released the Macintosh II, and Buckland got his hands on an early unit through his contacts at the company. This led Buckland to redesign the entire game to support the Mac II’s color graphics. Consequently, Crystal Quest became what Moss described as not just the first color game for the Mac but the “first colour-capable Mac program outside of Apple’s built-in system software.”

Shortly after completing work on Crystal Quest in early 1987, Buckland received a letter from Michael Greene, the owner of a small California-based software publisher, Greene Software, Inc. Greene wanted to publish Crystal Quest. Buckland agreed, and the game “climbed quickly into the upper echelons of Mac software charts,” according to Moss. In 1988, Greene also released the Critter Editor, a commercial repackaging of the toolkit Buckland created to develop Crystal Quest. This program allowed users to create their own levels and even import additional graphics and sounds into Crystal Quest. (The version of Crystal Quest that Paul Schindler demonstrated included the Critter Editor.)

Not long after this Chronicles episode aired, Greene Software merged with CasadyWare, a developer of PostScript fonts, to form Casady & Greene, Inc., which continued to publish Macintosh software until it closed in 2003. In 1993, Casady & Greene published a sequel to Crystal Quest called Crystal Crazy: The Quest Continues, with Buckland turning over programming duties to an old school friend of his, Alasdair Klyne.

The following year, 1994, Buckland started his own game development company, Stainless Games, with Neil Barnden, also a friend from school. Stainless Games remains active under Buckland’s leadership as of this writing. The company is best known for its Carmageddon series of racing-combat games. In 2006, Stainless ported Crystal Quest to Xbox Live Arcade. In 2016, Game Mechanics LLC released a licensed “revival” called Crystal Quest Classic, which is still available on Steam.

Broderbund Shuffles Into the Mac

Like Crystal Quest, Shufflepuck Café was the product of a solo developer with great enthusiasm for the Macintosh. Christopher Gross recalled to Retro Gamer magazine that the Mac “struck me as a qualitative shift” in computing, particularly with respect to incorporation of a mouse into the user interface. Gross was so enamored by the Mac’s potential that he quit graduate school–he was studying computer science–and started programming on the Mac full time.

Gross initially sold a “couple of little games” to a floppy-disk based Apple magazine, according to Richard Moss. These first games drew graphics directly to the Macintosh’s screen. But Moss said Gross wanted to try out a new technique he read about in a magazine “that involved drawing changes off-screen and then quickly copying them in while the screen refreshed.”

To test this new technique, Gross created a simple puck animation. Initially, he tried to build a shuffleboard game around this animation–Gross lived near what Moss described as a “famous shuffleboard club”–but the physics were more closely related to an air hockey table. So he ended up creating an air hockey game demo that he called Shufflepuck.

In addition to submitting Shufflepuck to his usual disk-based magazine, Gross also sent it to a number of existing Apple software publishers. Broderbund, which had long been associated with the Apple II but had never published a native Macintosh game, decided to take a chance on Shufflepuck. As Moss explained:

Broderbund designers Gene Portwood and Lauren Elliott were very taken by the Shufflepuck demo. They had a vision of how it could work as a commercial game. Both Portwood and Elliott had been integral to the creation of the Carmen Sandiego games, but they’d been somewhat constrained by the series’ educational bent, so they saw Shufflepuck as an opportunity to play around and do something different.

Under Broderbund’s guidance, Shufflepuck became Shufflepuck Café. It took place in a Star Wars and Casablanca-inspired subterranean space bar – a rowdy meeting place for a quirky and diverse cast of alien races who all share a passion for air hockey. With the sole exception of a robot arm that would appear to draw the score on the blackboard, Portwood and Elliott created all of the characters.

Broderbund ended up selling about 20,000 copies of Shufflepuck Café, which wasn’t bad for a Macintosh game in the late 1980s. Obviously, Broderbund ported the game to other platforms, although Moss noted those computers without mouse support “struggled.” On the other hand, the non-Macintosh versions were all in color, while the original was monochrome.

Christopher Gross does not have any other computer game credits that I could find, and even with respect to Shufflepuck Café, his role in active development apparently ended after Broderbund accepted his demo, as Portwood and Elliott worked independently from him.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was originally broadcast during the week of December 1, 1988.

- Stewart Cheifet recorded his cold open for this episode outside J. Callaway’s Christmas, a year-round Christmas store then located in Las Vegas, Nevada. Presumably, Cheifet taped this while he was in Vegas for the COMDEX/Fall ‘88 show, which is the subject of the next episode.

- Alan Kay’s Dynabook concept is superficially similar to modern tablet computers such as Apple’s iPad. But Kay himself explained in a 2019 post that he saw the iPad as a “simple media consumption” device incompatible with his larger educational goals for Dynabook. Notably, he said it was impossible for Apple users–including children–from making “actively programmable things on the iPad and shar[ing] them on the Internet.” He also envisioned the Dynabook as requiring some sort of physical keyboard as opposed to a purely touch interface.

- Al Thoman owned and operated the Friendly Computer Store in San Mateo County from 1982 to 2002. Thoman later joined TeraRecon, a 3D imaging company, as its vice president of sales.

- Epyx, Inc., published Home Video Producer for the Apple II, Commodore 64, and IBM PC. Epyx was primarily a game publisher, and its only other non-game software products released in 1988 were Print Magic, a clone of Broderbund’s The Print Shop, and Sticker Maker. Reviewing Home Video Producer for Compute!, Ed Ferrell was largely complementary, saying the program “makes it easy for anyone to create good titles.” His main critique was that due to the placement of the eraser head on most home video recorders of the time, adding titles to a previously recorded tape “creates an unattractive and annoying blip on the head and tail of the inserted video piece.”

- Utah-based Gazelle Systems developed OpTune, which was used mostly as a disk defragmentation utility for MS-DOS computers. Eric Ruff founded Gazelle Systems in 1985. The company’s most notable product was probably Q-DOS, a text-interface file manager that competed against Norton Commander. In February 1993, Ruff sold the financially struggling Gazelle to Sig Schreyer, a former Atari and Commodore executive, who also took over as CEO. Schreyer died from heart disease two years later, and Gazelle Systems ceased operations shortly thereafter.

- Canadian game designers Don Mattrick and Brad Gour developed Grand Prix Circuit for Accolade through Mattrick’s company, Distinctive Software, Inc. Founded in 1982, Distinctive Software developed a number of sports games for Accolade and other publishers. In 1991, Electronic Arts purchased Distinctive for $11 million in a mostly-stock deal and turned it into EA Canada (now EA Vancouver), the company’s principal sports game development studio.

- The Chocolate Byte novelty “disks” started out as a marketing stunt. Michael Cahlin, who ran Los Angeles-based Cahlin/Williams Communications, told the Los Angeles Times that he first developed the idea of distributing a “thin slab of chocolate in the shape of floppy disc” back in 1984 to help sell a chocolate-themed cookbook. Retailers ignored the cookbook, he said, but loved the chocolate disks. So Cahlin created a standalone business, Chocolate Software Co., which sold about 75,000 units between 1984 and 1988, according to the Johnson City Press in Tennessee. Sales continued until at least 1990. (Cahlin also sold a Valentine’s Day-themed version called “The Love Byte.”)

- Founded in 1883, Massachusetts-based Parker Brothers was best known as a manufacturer of traditional board games and jigsaw puzzles. The company started producing electronic games in 1977 and later entered the home video game cartridge market. After the latter market collapsed in 1983, Parker’s parent company, General Mills, merged it with Kenner Toys to form Kenner Parker Toys, Inc., which was sold in 1987 to Tonka Corporation. Talking Baseball seems to have been a last-ditch attempt to revive interest in Parker’s electronic games business. The now-Tonka subsidiary premiered Talking Baseball at a February 1988 event held at New York’s famous 21 Cub. San Francisco Giants manager Frank Robinson played the game against New York Yankees left fielder Lou Piniella. Alas, Talking Baseball wasn’t a home run for Parker Brothers. While some retailers initially sold the product for around $100 during the 1988 holiday season, two years later I found ads trying to dump remaining stock for under $20. And by 1991, Parker Brothers itself was no more, with Hasbro, Inc, acquiring Tonka and shutting down Parker Brothers as an active company.

- While Accolade did not have a Formula One license for Grand Prix Circuit, the game did feature representations of eight actual race courses used during the 1987 F1 season. Actually, one of the circuits–Canada–was based on the 1986 race configuration. The 1987 Canadian Grand Prix was canceled due to a dispute between Canada’s two largest beer companies–Labatt and Molson–over who had the right to sponsor the race. According to Ron Levanduski of the Elmira Star-Gazette in New York, Labatt had promoted the Canadian Grand Prix since 1978. But a new promoter came in for 1987 and awarded the sponsorship to Molson, prompting Labatt to sue and obtain a preliminary injunction against the City of Montreal, which prevented the 1987 race from going forward. Labatt later dropped its lawsuit, allowing the Canadian Grand Prix to resume in 1988 under Molson’s sponsorship.