Computer Chronicles Revisited 119 — The Apple IIc Plus, Apple GS/OS, and Paintworks Gold

Apple Computer launched the Apple IIgs in September 1986 as the next generation of its venerable Apple II line. Strictly speaking, the IIgs was not an Apple II. The original Apple II designed by Steve Wozniak in 1977 was based on an 8-bit MOS Technology 6502 microprocessor. Subsequent revisions, including the Apple IIe and IIc, were then built around the 65C02, an enhanced, lower-power version of the 6502 produced by Western Design Center, which continues to manufacture the chips to this day.

The Apple IIgs, however, was built on another Western Digital design, the 65C816. Essentially, the 65C816 was a 16-bit CPU designed to be backwards-compatible with the 8-bit 6502 and 65C02 microprocessors. The IIgs could therefore run 16-bit programs natively as well as (most) 8-bit programs designed for the older Apple II machines in a special “emulation mode.”

Apple’s decision to emphasize compatibility with the existing Apple II software library marked a stark contrast with companies like Commodore International and Atari Corporation, which produced 16-bit computers–the Amiga and 520ST, respectively–that were wholly incompatible with their prior 8-bit machines. Of course, Apple had the Macintosh, which was incompatible with the Apple II, but that still begs the question: Why did Apple go to the trouble of making a 16-bit machine to keep running 8-bit software?

One reason was the educational market. As anyone who attended a public school in the United States in the 1980s or early 1990s–myself included–can tell you, the Apple II was the default computer in the educational market. According to an April 1986 BusinessWeek report, about 54 percent of K-12 classroom computers in the United States were Apple II machines. This was triple the market share of the next-closest competitor, Tandy/Radio Shack, and dwarfed IBM’s estimated 3-percent market share.

Indeed, in that same BusinessWeek report, Apple CEO John Sculley effectively confirmed a replacement for the Apple II–what would be the IIgs-was coming in the fall to help protect the company’s lead in the educational market against an expected offensive from IBM. “Educators don’t have the luxury of writing off computers in 3 to 5 years,” Sculley noted before adding, “It would be naive to be complacent.”

IBM’s educational strategy was to dump millions of its unsold PCjr machines on schools by offering trade-in credits and heavy discounts. BusinessWeek added that IBM also planned to create school-specific software packages, something Apple had mostly left to third-party developers. Other competitors, including Tandy and Commodore, planned to offer their own discounted IBM PC compatibles to schools in an attempt to further erode Apple’s market share.

Of course, Apple’s real long-term plan was to move the educational market onto its newer Macintosh platform. But given the Mac’s high upfront cost and limited software library in 1986, that wasn’t a practical option for most schools. It wasn’t until October 1990 that Apple came up with a better solution in the form of the Macintosh LC, an entry-level Mac that came with an optional Apple IIe card, allowing users to run both Apple II and Macintosh software on the same machine.

Why a New 8-Bit Computer in ‘88?

This next Computer Chronicles episode from November 1988 came at roughly the midway point between the introduction of the Apple IIgs and the Macintosh LC. The subject of this episode was the latest developments in the now-11-year-old Apple II line, including both a new operating system for the IIgs and a final revision to the original Apple II architecture, the Apple IIc Plus.

Stewart Cheifet opened the program by showing Gary Kildall an original Apple I computer contained inside of a briefcase (see below). Cheifet described the 1976 computer as literally a museum piece even though it was only about 10 years old. Given the current state of PC technology, what was the point of coming out now with a new 8-bit computer like the Apple IIc Plus? Kildall said that Apple got a head start over most of the other PC manufacturers. As a result, there was a lot of software produced and a good customer base for the Apple II. It was still a sufficient machine for most people to use in education and the home. So why shouldn’t Apple try and take advantage by releasing a new Apple II?

Sculley Reassured Apple II Users They Were Still Loved

Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment from Apple headquarters in Cupertino, California. Since its introduction over 10 years ago, Woods noted, the Apple II had proven to be a sturdy and persistent computer with a loyal following of devoted fans. There were now about 4.5 million Apple II machines scattered around the world. But company support for the Apple II line–at least in the eyes of its owners–hadn’t always been evident.

Apple CEO John Sculley agreed with that assessment, telling Woods that many Apple II users felt abandoned by the company because they hadn’t heard any encouraging messages from company executives. This had been a conscious decision as Apple was trying to convince business users that Apple wasn’t only in the home computer business–it was also in a position to provide very powerful business workstations. Without the success of the Macintosh in business, he added, Apple couldn’t afford the company’s huge investment in researching and developing proprietary technologies for both the Macintosh and Apple II.

Today, Woods said the Apple II had become three machines: the little-changed IIe, the colorful IIgs, and the portable IIc Plus. But increasingly, the Apple II series seemed to be headed in a different direction from the company’s most powerful–and expensive–computer in the Macintosh. Sculley said the main distinction between the Apple II and the Macintosh was the software base. The Apple II was largely focused on educational and enthusiast software, while the Macintosh was aimed at higher education and businesses.

Woods noted that Apple had other reasons besides owner loyalty to keep the Apple II line moving forward. For one, it was a billion-dollar industry all by itself. And the machine had captured over 60 percent of the educational market. Moreover, the installed base was enough to keep users and suppliers busy for many more years. Sculley added that there were many businesses that adopted the Apple II a long time ago and don’t want to give up that investment. For that reason, he said the Apple IIgs had found its way into many small businesses looking to upgrade without losing access to their existing software and files.

As with any kind of computer product, Woods said, the market determined whether a product lived or died. And John Sculley believed that customers for the Apple II would be around for sometime to come. He said Apple would continue to make the Macintosh as powerful as it could be, but that didn’t mean there weren’t still people who liked to drive the proverbial stick-shift and be closer to the real hardware, which was the experience you got with the Apple II.

Apple IIc Plus Blasted Math 4 Times Faster

Laura Kurihara and Bill Cleary joined Cheifet and Kildall back in the San Mateo studio for the next segment. Kurihara was the Apple product manager for the Apple IIc Plus. Cleary, a former executive with Apple and Activision, was president of Cleary Communications.

Kurihara was there to demonstrate the IIc Plus. Kildall asked about the new features. Kurihara said the original IIc had a built-in 5.25-inch floppy disk drive. The IIc Plus came with a built-in 3.5-inch disk drive, which was 3 times faster and offered 5 times the storage capacity per diskette. Additionally, the original IIc came with an external power supply “brick,” but the IIc Plus had an internal power supply. These were obvious changes, Kurihara said, but also necessary improvements to the IIc.

Kildall wanted to know more about the increased speed of the IIc Plus. Kurihara said the IIc Plus had a custom accelerator chip that enabled the CPU to run at 4 MHz, as opposed the 1 MHz clock speed of the original IIc. This was optional. The machine booted into 4 MHz mode, but through a keystroke the user could still run programs at the traditional 1 MHz speed. Kidlall noted that was important because many programs depended on 1 MHz timing to work properly.

Cheifet asked Kurihara to run a demo of the IIc Plus using Math Blaster Plus!, an educational software program published by Davidson & Associates. Specifically, Cheifet wanted to see how the program worked at 4 MHz versus 1 MHz.

Kurihara started by running Math Blaster Plus! at 1 MHz. The demo showed a small figure running back-and-forth across the bottom of the screen. The IIc Plus speaker clicked as the figure ran. Kurihara then reset the machine to run at 4 MHz.

While waiting for the program to reboot, Cheifet asked if Apple was concerned that including a 3.5-inch disk drive in the Apple IIc plus created problems for users, given that most Apple II software was still released on 5.25-inch floppy disks. Didn’t switching disk formats throw out that advantage? Kurihara said Apple was concerned about that during development, so it encouraged third-party developers to make that transition by releasing separate 3.5-inch versions of their programs. She noted that on the day of the IIc Plus’ introduction, Apple announced over 500 retail software applications were available on 3.5-inch disk.

Returning to the demo, Kurihara showed the Math Blaster Plus! figure running much faster along the bottom of the screen.

Cheifet then turned to Cleary and asked about the practical advantages of the IIc Plus and its greater speed. Cleary said there were home productivity applications like Claris’ AppleWorks and Broderbund’s The Print Shop that would benefit. More broadly, the IIc Plus would extend the life of the existing Apple II software library. He recalled a conversation he had when he was a marketing executive at Activision, where he was asked why the Amiga wouldn’t “knock off” the Apple II. At the time, Clearly said that the Amiga could knock of the Apple II if it could somehow manage to capture 60 percent of the educational market with 10,000 available software titles and 2.5 million users.

Turning back to Kurihara, Cheifet asked about peripherals for the IIc Plus. She showed off three external disk drives: The Apple UniDisk 3.5, which was specifically designed for the Apple II series; the Apple 3.5 Drive, which was originally designed for the IIgs but compatible with the IIc Plus; and the Apple 5.25 Drive.

Cheifet then asked Cleary if the IIc Plus would fill the same market niche as the older Apple II machines. Cleary said the IIc made sense as a home computer for people whose kids were in grades K-12 and already using the IIe at school. Following up, Cheifet asked Cleary if there was an ideal Apple II machine he’d like to see Apple release in the future. Cleary said ideally, he wanted a IIc-style machine that ran both Macintosh and Apple II software–an Apple “master machine,” as Cheifet jokingly described it–which included a flat-panel screen to make the entire unit portable. Cleary admitted, however, that would be a difficult product to justify from a cost standpoint.

Mac IIx a Preview of Apple’s Future Direction

Turning to the Macintosh for her final remote segment, Wendy Woods was back reporting from Apple HQ on the new top-of-the-line Macintosh IIx. Woods said the IIx broke new ground for Apple. It was the first Mac to use Motorola’s powerful new 68030 microprocessor. The IIx also came standard with 4 MB of RAM; ran at 16 MHz, making it 10 to 30 percent faster than the original Macintosh II; and most importantly, it was the first Apple product that could read and write files to the IBM PC/MS-DOS format.

Regarding that last feature, Scott Darling, the Macintosh IIx product manager at Apple, told Woods that the message Apple got most clearly was that people loved the Mac technology and wanted to use it. So the less painful Apple could make it to transition from old technology, the easier it was to sell the Mac.

Woods said the Macintosh IIx’s disk drive was operated by file exchange software, which could read and write 3.5-inch OS/2 or MS-DOS diskettes, Macintosh diskettes, or Apple II ProDOS diskettes. In an on-screen demo, a IIx read and converted a Lotus 1-2-3 file made on an MS-DOS laptop to a file that could be used in Microsoft Excel on the Macintosh.

Within a few years, Woods said this “top of the line” would become the “middle of the line,” and you could see the direction Apple was heading–a future of powerful color Macintoshes where the data from many kinds of machines were interchangeable.

Unleashing the Power of the IIgs

Anne Bachtold and Stuart Roberson joined Cheifet and Kildall for the final studio segment. Bachtold was the Apple IIgs product manager for Apple. Roberson was director of marketing for Activision.

Kildall opened by asking Bachtold to distinguish the IIgs from the rest of the Apple II line. Bachtold said the GS was the “top of the line” for the Apple II family, selling into both consumer and educational markets. The IIgs was still an Apple II, however, and it ran all of the existing Apple II software.

Bachtold then demonstrated Apple GS/OS, the latest revision to the Apple IIgs operating system (also known as System Software 4.0). While waiting for the OS to load, Kildall asked for more information about who was actually buying the IIgs. Bachtold said families and people who were interested in doing home productivity and K-12 education.

Beginning the GS/OS demo, Bachtold noted the operating system offered faster disk access and boot times over the previous System Software. GS/OS also introduced the concept of File System Translation (FST). Essentially, this allowed the user to access data files from other operating systems. Using built-in FST tools, you could access data on a High Sierra file system from an external CD-ROM drive. This enabled the use of CD-ROM applications like Microsoft Bookshelf with the IIgs. For her demo, Bachtold imported a data file from Bookshelf into MultiScribe, a IIgs-native word processor. Bachtold added that educational customers were particularly interested in this feature as it opened up the world of CD-ROM software.

Kildall followed up, asking Bachtold about other potential CD-ROM applications for the IIgs. Bachtold said any large-storage application such as an encyclopedia would be appropriate for CD-ROM. She added that Apple had only introduced its first CD-ROM drive in March 1988, and GS/OS represented the first time such a drive could be used with an Apple II machine.

Cheifet then asked Bachtold to demonstrate some of the other new features of GS/OS. Bachtold showed off two new utilities. The first was the Installer, which enabled the user to easily install new hardware device drivers. For example, you could install the CD-ROM driver. The second utility was the Advanced Disk Utility, which made it possible to partition hard disks. This was useful if you needed to run different types of files on the same hard disk. For example, you could have one partition to run Pascal and another to run ProDOS. The Disk Utility made it possible to add, resize, or delete partitions.

Turning to Roberson, Cheifet asked how important the IIgs was to third-party software developers like Activision. Roberson said Activision was dedicated to the IIgs, specifically the educational and home markets it served. He added that many of the older, established Apple II developers were now starting to shift their focus to the IIgs. Kildall asked about the actual size of the IIgs market. Roberson said the installed base for the IIgs was about 300,000 machines. Activision anticipated that during the 1988 holiday season, Apple would sell more Apple IIgs units than any other Apple machine.

Cheifet then asked Roberson to demonstrate Activision’s latest IIgs application, a paint program called Paintworks Gold. Roberson said Paintworks Gold was one of eight products that Actvision published for the IIgs. Paintworks Gold was derived from Paintworks Plus, which was already in use at many schools.

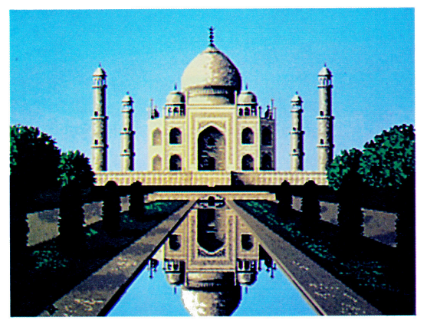

Turning to the demo, Roberson loaded an image of the Taj Mahal (see below). He then used two features called “Slippy Colors” and “Mask Colors” to add a reflection of the Taj Mahal to the pool below to the building. “Slippy Colors” defined colors for the lasso tool in Paintworks to slip around. Roberson used the lasso tool to select the image of the Taj Mahal itself. He then flipped that image and pasted it into the reflecting pool. Roberson next used the “Mask Colors” feature to eliminate those parts of the reflected Taj Mahal that should be covered by the grass. Finally, he changed the background colors of the sky to make it appear as a sunset.

DRAM Prices, Clone Competitor Kept IIc Plus Prices in Check

Perhaps the most telling reaction to the release of the Apple IIc Plus came from Dan Muse, editor in chief of the Apple II-focused inCider magazine, who rhetorically asked, “What if you announced a new computer and nobody cared?” While Muse said the IIc Plus was “not an unattractive computer,” he was puzzled by the decision to include a faster CPU but not more memory. The IIc Plus contained the same 128 KB of RAM as the original IIc. This made little sense, Muse said, as it was the need for continuous disk access that made applications run slow on the Apple II, not the clock speed of the processor. And more memory meant less need to access the disk.

So why didn’t Apple offer more RAM with the IIc Plus? According to John Sculley, the main reason was that prices for dynamic random access memory (DRAM) soared in 1988. As friend of the blog Ernie Smith explained in a 2016 article, “After the computer industry slumped in 1985, prices for RAM chips fell to extreme lows.” This was then followed by the Reagan administration’s decision to impose tariffs on Japan after “the U.S. Commerce Department accused the Japanese chip industry of flooding the American market with RAM chips at a level below market rates, with the goal of pushing American companies out of the market.” This then made manufacturers more timid about producing DRAM, particularly at lower capacities. As a result, Smith noted:

By July of 1988, the increasing RAM prices, which had slowly crept up in the early parts of the year, surged. A megabyte of RAM, according to John C. McCallum’s price analysis, had surged in price from $199 to $505 in a single month, and the cost of a 256k DRAM chip had surged from $2.95 at the beginning of 1988 to $12.45—a price level maintained for nearly a year. Eventually, 1-megabit chips took over the market, but the price issues were causing many RAM-buyers to hold out before purchasing any more chips.

Apple’s response to this surge in DRAM pricing was to announce its own across-the-board price increases in September 1988. For example, Apple raised the base price of the IIgs from $999 to $1,149. Understandably, this upset third-party developers already struggling to support the relatively small IIgs market. William Campbell, the head of Apple’s own software spin-off Claris, told the San Francisco Examiner, “Price increases can’t help,” and that he “didn’t know the strategy behind” the price increases. Mediagenic (Activision) executive Steve Roach added the price increase “could mean a net reduction in software sales for us.”

Neither Campbell nor Roach accepted higher memory prices as a justification. Indeed, the Examiner cited another software company executive who said the “IIgs was overpriced to start and now it’s worse.” There was also a split of opinion within Apple itself, with the company’s “financial group winning over others who worry that the move could result in persuading some potential buyers to select other machines.”

That said, Sculley opted not to raise prices for the older Apple IIe, IIc, and Macintosh Plus machines, and the IIc Plus was actually priced below the original IIc. The base price for the IIc Plus–the computer with no monitor–was $675, about $100 less than the original IIc. Adding a monochrome display raised the price of the Plus to $859, and a color monitor would set you back $1,099. In contrast, the original Apple IIc cost $950 with a monochrome display and $1,299 with a color monitor.

In theory, Apple could have kept the prices for the IIc Plus the same as the IIc and offered more base memory, as Dan Muse suggested, but I suspect John Sculley didn’t go down that route because hitting a lower price point for the IIc Plus was its main reason for existing in the first place. The truth was that Apple didn’t need to release another machine in the Apple II line in 1988. That it do so was likely for two reasons: First, Sculley and his marketing team wanted to have some new product in retail stores for the 1988 holiday season. (The other new Apple machine discussed in this episode, the Macintosh IIx, was a high-end engineering workstation priced at $9,369, so not a consumer product.) Second, Apple was likely worried about potential market erosion from lower-end competition–specifically the Laser 128.

In 1986, Hong Kong-based Video Technology Computers Ltd. (VTech) released the Laser 128 in the United States. The Laser was an Apple II clone that used a similar design to the original IIc. Apple II clones had become quite commonplace in Asian markets by this time, but Apple had been successful in using its legal and political clout to keep such machines out of the United States. But the Laser 128 managed to enter the country through a mail-order distributor, Portland-based Central Point Software, who initially sold the Apple II clone for just $395 (no monitor included).

In December 1987, VTech acquired a controlling interest in Central Point Software and turned it into a U.S. subsidiary, which continued to distribute the Apple II clones under the name Laser Computer, Inc. Around the same time that Apple released the IIc Plus, Laser Comptuer announced the Laser 128 EX/2. inCider even reviewed the two machines side-by-side in its November 1988 issue. With respect to the EX/2, reviewer Eric Grevstad said the clone was “more than a match for the IIc Plus.”

While Grevstad conceded Apple’s new machine was “slightly quicker”–the EX/2’s 65C02 microprocessor topped out at 3.6 MHz rather than the IIc Plus’ 4 MHz–Laser managed to address Dan Muse’s concerns about the lack of additional memory. Although the EX/2 came with the same 128 KB of built-in RAM as the Apple IIc and IIc Plus, it also included memory expansion card. Basically, this was a pre-configured slot enabling the user to plug in additional 256 KB DRAM chips, adding up to 1 MB of additional memory to the EX/2. Performing a similar memory expansion on a IIc or IIc Plus required opening up the machine and installing an internal daughter board, which wasn’t exactly something most home computer users would want to do.

And unlike Apple, Laser Computer decided to hedge its bets when it came to the internal disk drive. Like the IIc Plus, the Laser 128 EX/2 included a 3.5-inch floppy disk drive standard. But Laser also offered the EX/2 with a 5.25-inch disk drive. The 3.5-inch model had a suggested retail price of $549 while the 5.25-inch version was just $499. While Laser never enjoyed the sales or distribution reach of “real” Apple II computers, this pricing helps to explain why Apple decided to hold the line and lower the price of the IIc Plus relative to the IIc.

Ultimately, the IIc Plus proved to be a short-lived product. Apple officially discontinued the computer in November 1990, not long after the launch of the Macintosh LC, which as I noted in the introduction had an optional “Apple IIe card” that enabled the Mac to run legacy Apple II software.

The Road to GS/OS

Unlike many microcomputers developed in the late 1970s, Apple did not go with Gary Kildall’s CP/M as the operating system for the original Apple II. Indeed, when the Apple II first released in 1977 there was no “disk operating system,” since there was no disk drive. Apple II users initially had to load and save files exclusively from cassette tapes until Steve Wozniak finished work on a disk drive system–the Apple Disk II–which the company released in June 1978.

Wozniak decided not to write his own operating system for the Disk II, instead outsourcing that task to an outside firm. The finished product was known as Apple DOS. It was a pretty bare-bones OS. Apple DOS could only read single-sided 140 KB floppy disks used with the Disk II. It could not support any type of hard disk drive or even use the RAM as a drive, as there was no memory management capability.

In these early days, there was one notable alternative to Apple DOS, which was Pascal. The University of California, San Diego (UCSD), developed a machine-independent implementation of the Pascal programming language known as the UCSD p-System. This included an Apple II version–Apple Pascal–released in August 1979.

The following year, Apple released the Apple III, which contained a completely new operating system. Internally codenamed “Sara’s Operating System” after one of the engineer’s daughters, the final release was called the “Sophisticated Operating System” or SOS–an appropriate signal for the ultimately ill-fated Apple III. Unlike Apple DOS and Pascal, SOS supported a hierarchical (rather than flat-file) file system. More importantly, SOS supported multiple disk drives and memory management. The downside was that SOS required at least 256 KB of RAM to function properly, which made it a non-starter for Apple II machines. (The Apple II Plus, which released in June 1979, couldn’t support more than 64 KB of RAM.)

Apple took what it learned from SOS, however, and incorporated it into a new Apple II-specific operating system called ProDOS, which first released in October 1983. ProDOS was not only up to eight times faster than Apple DOS in terms of disk access, it could support multiple types of disk devices and a hierarchical file system. And it only required 64 KB of RAM.

Actually, ProDOS could not address more than 64 KB of RAM. That was fine when dealing with 8-bit Apple II machines. But when Apple introduced the IIgs, which came with a 16-bit CPU and 256 KB of RAM standard, it had to “extend” ProDOS to compensate. The IIgs initially shipped in 1986 with an operating system that Apple called ProDOS 16. At the same time, Apple renamed the older Apple II operating system ProDOS 8.

ProDOS 16 basically allowed older Apple II software written for ProDOS 8 to work properly on the IIgs. The trade-off was that any software written for the 16-bit CPU had to be translated on the fly to use ProDOS 8 system calls when interacting with the disk drive. This meant 16-bit applications often ran much slower than the IIgs hardware could theoretically support.

This led Apple to develop GS/OS, a true 16-bit operating system designed specifically for the IIgs. While maintaining backwards compatibility with ProDOS 16, GS/OS was, as explained in this episode, also designed to be file-system independent. That is, GS/OS could theoretically handle files written for any file system, including CD-ROM and MS-DOS. And of course, GS/OS also enabled the IIgs to support a Macintosh-style graphical user interface.

Officially, Apple designated its September 1988 update to the Apple IIgs operating system–System 4.0–as the first release of GS/OS. (The prior releases were all ProDOS 16.) Apple continued to revise and update GS/OS through System 6.0.1, which released in May 1993, five months after Apple discontinued the IIgs itself.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was first broadcast during the week of November 22, 1988. The recording on the Archive is a rerun that aired in February 1989.

- Laura Kurihara left Apple in 1989. In the 1990s, she transitioned from technology to the culinary arts, working as a hotel cook and later as a pastry chef for a specialty supermarket chain in Arizona.

- Bill Cleary was a marketing manager at Apple and Activision. In 1987, he founded Cleary Communications, which later became CKS Group after he partnered with two former Apple colleagues, Mark Kvamme and Tom Suiter. CKS Group primarily served as an advertising agency for Silicon Valley companies, including Apple, eBay, and Yahoo. In December 1995, CKS Group held a $48.9 million initial public offering. Three years later, USWeb Corp., an Internet consulting company, acquired CKS Group in a $344.4 million stock swap. Cleary left the company after the acquisition.

- Scott Darling began his career at Intel before moving to Apple in 1987. He left Cupertino in 1990 and returned to Intel for a 16-year stint, including seven years as vice president of the company’s venture capital arm. In 2012, Darling joined Dell Technologies, where he’s been president of its venture capital arm since 2016.

- Stuart Roberson left Activision in 1990 and later spent three years at Apple as a product marketing director. After leaving Apple in 1996, Roberson joined PictureWorks Technology, Inc., a developer of digital photography software for real estate websites, as its vice president of marketing. In 2000, Internet Pictures Corporation acquired PictureWorks in a stock swap valued at $159.3 million. Roberson remained with Internet Pictures as a senior vice president until 2003. In 2004, Roberson and his wife started Store Inside, a San Jose, California-based storage facility for vehicles, which they continue to own as of this writing. The Robersons also started a Lake Tahoe, California-based vacation rental company that they actively ran until 2024.

- Jan Davidson, a former college teacher, developed the original Math Blaster! in 1983, which she published through Davidson & Associates, a company she co-founded with her husband, Robert Davidson. The company released Math Blaster Plus! in 1987 for MS-DOS and the Apple II, with the Apple IIgs version published shortly thereafter.

- Like the Apple IIc Plus, John Sculley formally announced the Macintosh IIx at the AppleFest ‘88 show in San Francisco, which was held in late September. Many news reports speculated that Apple released the IIx as a “preemptive strike” against former chairman Steve Jobs, who announced his NeXT Computer a couple of weeks later. The NeXT and the Macintosh IIx both used a Motorola 68030 CPU.

- Luc Barthelet and Henri Lamiraux developed Paintworks Gold for Activision through their company Version Soft, Inc. In May 1988, Activision changed its corporate name to Mediagenic, although it kept “Activision” as a publishing label. In October 1989, Wendy Woods reported that Mediagenic planned to divest Paintworks Gold as part of a larger sell-off of the company’s non-gaming titles. (I discussed Activision/Mediagenic’s struggles during this time in an episode of Chronicles Revisited Podcast.) Barthelet and Lamiraux ended up selling their own company to Electronic Arts. Barthelet went on to enjoy a long career at EA, including a seven-year stint as general manager of its Maxis subsidiary, before spending six years at game engine developer Unity. As for Lamiraux, he spent 23 years working at Apple, eventually becoming vice president of engineering in charge of iOS. Lamiraux retired from Apple in 2013.

- The “Apple I in a briefcase” that Stewart Cheifet showed Gary Kildall during the studio introduction was likely on loan from Apple itself. A picture of the same briefcase computer was featured in the owner’s guide for the Apple IIc Plus. (Cheifet also showed off a different Apple I at the start of a 1984 episode co-hosted by Herbert Lechner.)