Computer Chronicles Revisited 118 — EISA, MCA, and the Wells American CompuStar

In June 1978, George Morrow and Howard Fullmer made a formal presentation at the National Computer Conference in Anaheim, California, proposing an official standard for the S-100 bus. The S-100 bus originated nearly four years earlier with the MITS Altair, the Intel 8080-based microcomputer kit famously featured on the cover of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics. The Altair’s success among the small community of computer hobbyists spawned a number of early companies dedicated to either cloning the Altair or producing peripherals compatible with the S-100 bus. This included Morrow’s Thinker Toys (later renamed Morrow Designs, Inc.) and Fullmer’s Parasitic Engineering, Inc.

MITS, of course, was not happy about all these clone-makers. It never intended the S-100 bus to be an open standard and viewed these hobbyist startups as parasites. Indeed, Fullmer named his company Parasitic Engineering after MITS founder Ed Roberts used the term “parasite” to describe the hobbyists.

But Morrow and Fullmer eventually prevailed, and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Computer Society formally approved the IEEE-696 standard for the S-100 bus in June 1982. Of course, by then there was a new player in the microcomputer market in the form of the IBM PC, which used a completely different bus that came to be known as the Industry Standard Architecture or ISA bus.

The success of the PC and its ISA bus spelled the end of the commercial market for computers based on the S-100 bus. By 1983, Howard Fullmer had closed Parasitic Engineering and joined Morrow Designs, which managed to hold out until 1986. By that point even George had abandoned the S-100 bus for a PC clone in the form of the Morrow Pivot.

Of course, IBM’s success attracted a new generation of clone-makers. And unlike the Altair-inspired hobbyists of the 1970s, these new companies were well-funded by venture capital and employed experienced industry executives in key management roles. Foremost among these clone-makers was Compaq, a Texas-based company founded in 1983 by three senior managers from microchip giant Texas Instruments. In less than four years, Compaq became a Fortune 500 company, and by 1989 the company posted $3 billion in annual revenues.

Unburdened by IBM’s bureaucracy and core mainframe business, Compaq and the other clone-makers succeeded in turning the ISA into a de facto open standard for the personal computer. More importantly, they were able to innovate and ship new products based on the ISA bus more quickly than IBM. In response, IBM famously tried to change the standard with the April 1987 debut of its PS/2 line, where most of the machines were based on a redesigned BUS it called Micro Channel Architecture (MCA).

Now, the MCA bus was a substantial technical improvement over ISA. For one thing, MCA was a 32-bit bus, as opposed to the 16-bit ISA. MCA-based expansion cards could also run much faster and handle higher data loads, which was especially important for networking and high-resolution graphics.

But the downside to MCA–at least from the perspective of the clone-makers and most PC users–was that existing ISA cards were incompatible with the new architecture. Even worse, IBM claimed a number of patents on MCA. This meant that anyone who wanted to design a PC or expansion card based on MCA would have to pay royalties to Big Blue or face a potential patent infringement lawsuit.

Bus Wars

In September 1988, the clone-makers fought back. A group led by Compaq and dubbed the “Gang of Nine” held a press conference in New York City to announce their own plans to create a standard 32-bit bus called the Extended Industry Standard Architecture (EISA). Basically, EISA would maintain backwards compatibility with existing 16-bit ISA expansion cards while allowing for new 32-bit cards free of any IBM patents.

(In case you’re wondering, the other members of the Gang of Nine were Tandy, AST Research, Hewlett-Packard, Epson, NEC, Olivetti, Zenith Data Systems, and Wyse Technology.)

Undeterred, IBM held a rival press conference to denounce EISA as nothing more than an attempt to keep the dying ISA bus–also known as the AT bus–alive. (At the same time, IBM announced a new, low-end PS/2 machine that kept the traditional AT bus.) IBM executives strongly hinted that elements of the proposed EISA standard would still infringe upon Big Blue’s patents. Bill Lowe, the IBM executive in charge of the PC division, told an industry conference later that month that customers didn’t want “two bus standards” and that he couldn’t see “why anybody would be interested” in EISA.

Well, two people who were very interested in EISA were Stewart Cheifet and Gary Kildall, who kicked off their first in-studio episode of Computer Chronicles season six by talking about the escalating “bus wars.” (For context, this episode taped in late October 1988, about a month after the dueling press conferences.) Cheifet showed Kildall two computer motherboards. The first was from an AST Premium/286 using the ISA bus, the second an IBM PS/2 motherboard using the MCA bus. They both looked the same to Cheifet. So he asked Kildall to explain what exactly was a bus, and why should it matter to an end user which bus was in their comptuer?

Kildall said it came down to standards. Just like an operating system provided a standard for software, the bus provided a standard for the parts of a computer to communicate with one another electrically. Physically, the bus was defined by the pins on an expansion card, which contained address and data lines. This, in turn, defined how much data you could move between the computer’s CPU and memory.

Continuing, Kildall noted that the AT bus had been around for several years now and there were lots of optional expansion boards available. IBM’s MCA bus hadn’t been around as long–and the install base wasn’t as large–so there weren’t as many options right now. But that would change as the PS/2 market grew.

The Depreciation Menace

Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment, which started at Infomax Computers, a computer retail store in Oakland, California. Woods said the difficult task of choosing which computer to buy had been made more difficult recently thanks to the introduction of new bus architectures. Not surprisingly, IBM’s new MCA, the rebellious clone-makers, and Apple’s NuBus architecture for the Macintosh II had made things difficult for a lot of buyers.

Stephen Beals, Infomax’s director of corporate services, told Woods that in this industry, when a new product was introduced and a continuation of the old product was not made available, it caused some problems, because there wasn’t enough time to change over.

Among larger companies, Woods said, the decision to change or not to change was based, in part, on the equipment already in-house–and whether there was a genuine and immediate need to upgrade the hardware.

Woods spoke to S. Edmund Johnson, the director of engineering with KGO-TV in San Francisco, who said it was too much financially for him to consider switching to new hardware right now. He wouldn’t even consider it. KGO needed to depreciate its existing equipment, some of which was less than two years old. It therefore wouldn’t make financial sense to move on.

Woods said that while most PC buyers wouldn’t object to the improvements offered by new bus designs, such as smaller size and multitasking, some users had lingering concerns about the potential drawbacks. KGO’s Johnson noted that one problem with getting into multitasking was that it took a tremendous amount of learning time for the user, which was itself a big investment.

Historically, Woods concluded, the latest competition in the PC market was nothing new to retailers and may, in fact, be settled by computer users.

Attack of the Clones

Bob Kutnick and Richard Archuleta joined Cheifet and Kildall back in the studio. Kutnick was the director of strategic projects with AST Research. Archuleta was a research and development section manager with Hewlett-Packard. As previously noted, AST and HP were both members of the “Gang of Nine” supporting the proposed EISA bus.

Kildall opened by asking Kutnick to explain EISA. Kutnick said the term stood for “enhanced industry standard architecture.” (It was actually announced as “extended” rather than “enhanced,” but maybe that hadn’t been fully resolved at this point.) He said EISA was a natural evolution of the AT bus into the 32-bit realm. Just as we went from the PC to the PC-AT, we now would go to EISA machines.

Kildall asked who was supporting EISA. Kutnick said there were over 100 companies that applied for the specification. He then mentioned the Gang of Nine that originally came together to announce the standard. EISA provided extended benefits in the long run such as bus arbitration, which would enable the user to run multiple processors on the same motherboard. There were also enhancements to direct memory access (DMA) operations.

Cheifet asked for a demonstration of how software would actually run on EISA as compared to ISA. Kutnick opened dBase II on a machine using an AT bus–I assume it was an AST Premium/286–which then ran a scrolling list of a database containing a list of computer stores. Kutnick emphasized how fast the scrolling was; but if he opened a second program simultaneously, in this case Lotus 1-2-3, the scrolling in dBase slowed down noticeably. He then opened a third application to make the slowdown even more apparent. Under an EISA system, however, Kutnick said you could have a board with multiple CPUs, with each individual application running on its own independent processor. This meant the user wouldn’t even notice a slowdown. (To be clear, Kutnick did not actually demonstrate a computer with an EISA bus, as it didn’t exist yet.)

Cheifet pointed out, however, that the MCA bus had already addressed this problem. Kutnick said the MCA bus was very similar to EISA, but there was a difference in the outlay of the actual expansion cards. To demonstrate, he showed an existing ISA card and compared it to an MCA card. The MCA card was much smaller, but Kutnick argued that this was a disadvantage, because you needed to design application-specific integrated circuits (ASIC) to achieve the degree of miniaturization necessary to fit into an MCA bus. A card designed for ISA–and thus EISA–did not require ASICs and thus could rely on existing parts and circuit designs.

Kildall wondered if that meant that EISA would be carrying significant baggage–or technical debt, as we would call it today–over from ISA. Was there anything from ISA you wouldn’t want in a new standard? Kutnick conceded there was some baggage, but he reiterated that EISA was a natural 32-bit evolution of the AT standard.

Turning to Archuleta, Cheifet asked him why HP was involved in the Gang of Nine. Archuleta said HP did a lot of investigation into MCA since its introduction last year. There were also a lot of conversation between HP and its customer base. And while the customers liked many of the enhancements offered by MCA, they had a problem with transitioning from the base of machines they currently owned and making a dramatic change to a new architecture. (In other words, they didn’t want to throw out their existing PCs and buy all-new PS/2 machines.) He also seconded Kutnick’s concern that third-party hardware vendors faced difficulty in trying to fit their designs into the smaller MCA cards. So HP supported the goal of trying to naturally evolve the AT bus while incorporating the best features from MCA.

Kildall asked how long it would take to actually get EISA products to market. Archuleta said it would happen by the end of next year (1989). Kutnick added that EISA was really a statement of direction: If you had an existing base of (AT) machines, it was now expandable into EISA. AST’s customers saw this as insurance allowing them to buy AT machines and expansion cards today while still having the ability to expand later.

Cheifet asked if this was a technology battle between the different buses or was it really just a marketing battle. Sticking to his talking point, Kutnick said yet again this was a natural evolution of the AT bus. It was basically adding another connector to existing AT boards.

A Nu Hope

Meanwhile, Wendy Woods traveled to Apple Computer headquarters in Cupertino, California, to discuss NuBus, the architecture used in the Macintosh II line. Woods noted that Apple decided to go with a bus design that already had a few miles on it in NuBus, an architecture created by Texas Instruments and already in use by over a dozen other computer companies.

NuBus represented several technical breakthroughs. Mark Orr, a product manager at Apple, told Woods that NuBus was a very fast bus. NuBus was originally developed for artificial intelligence (AI) research at MIT, which meant it was designed to support a tremendous amount of data movement between individual cards and the CPU. NuBus could also support a wide variety of card architectures. From the point of view of a developer, Orr emphasized, NuBus provided a large board area, which made it very inexpensive to develop boards. This in turn meant there would be a larger number of expansion cards available for the Macintosh II.

Woods added that unlike some bus structures, NuBus didn’t require a specific board in a specific slot. All NuBus cards worked with all other NuBus cards and all were interchangeable in all of the slots. Apple also believed that the NuBus architecture had staying power and a track record. In fact, some 60 firms were expected to adopt NuBus for their peripheral cards and computers.

The Empire Strikes Back

Chet Heath, a senior engineer for hardware architecture at IBM, joined Chiefet and Kildall back in the studio for the next segment. Cheifet noted that Heath was often credited as the “father” of the MCA bus. Heath quipped that he was the “oldest living survivor of Micro Channel Architecture.”

Kildall asked why IBM opted to create a new architecture instead of simply extending the ISA bus. Heath said the problem was the AT cards. To extend the system’s capabilities to support faster input-output and multitasking, IBM needed the cards to be less dependent on the CPU. This and a preponderance of other problems with the AT bus drove IBM towards finding a new bus solution.

To illustrate what he meant, Heath showed a prototype of a 110-pin connector for the AT bus that Heath’s team built back in 1984. (For context, 16-bit ISA cards used 98-pin connectors, while 8-bit cards used 62-pin connectors.) Essentially, this connector was an attempt to add features to the existing ISA bus. But Heath said they had difficulty getting the 110-pin cards to run in the same environment as existing AT cards that depended on the CPU.

Kildall, addressing the patent troll in the room, asked if MCA was a proprietary architecture. Heath deflected, claiming he didn’t understand the use of the term “proprietary.” That would mean that MCA was not available to other manufacturers. But MCA was, in his view, one of the best-documented architectures around and available for use by anyone.

Heath then demonstrated MCA using an IBM PS/2 Model 60. He noted there were currently about 550 different add-on cards available for MCA. But few of them took advantage of the feature he wanted to demonstrate, which was built-in support for multiple processors in a single system. The Model 60 in the studio was a test unit with a special tool designed by IBM engineer Ernie Mandese.

Heath used a lot of technical jargon, which makes it difficult to recap. But the crux of the demo was that the PS/2 could independently run two different programs–even two different operating systems–under the MCA bus. Kildall asked how many total processors could run on an MCA bus before you started running into memory access problems. Heath said in theory, you could run up to 16 processors on a single MCA bus, assuming each processor had access to its own storage and memory.

Cheifet then asked Heath for his reaction to EISA and the criticism of MCA. Heath said he didn’t understand the criticism of MCA. As for EISA, he didn’t think it was necessary to take and reproduce a concept that was fundamentally equivalent to MCA. If one understood that you didn’t need the old add-on cards–that they would hamper you in moving forward–and most of the functions had been reproduced on the 550 or so existing MCA cards currently available, then you had a basis on which people could work. Ultimately, he said the efforts going into EISA should be channeled into working with the MCA standard.

Finally, Cheifet asked when consumers would actually start to see the benefit of MCA. Heath acknowledged that it was taking existing add-on card manufacturers time to revise their designs to comply with MCA. But he expected to see some product announcements at the upcoming fall COMDEX show.

The Best of Both Worlds?

For the final segment, Winn L. Rosch and Michael E. Hoyle joined Cheifet and Kildall. Rosch was a contributing editor with PC Magazine. Hoyle was a product manager with South Carolina-based Wells American Corporation.

Kildall asked Rosch for his opinion on the EISA-versus-MCA battle. Rosch said it was a hard battle to call, because you’re comparing something that’s been around for about two years (MCA) and something that’s going to be about 18 to 24 months before you see anything (EISA). You couldn’t characterize a battle where one of the competitors was still an unknown. But his initial impression was that MCA was looking to the future and provided something that would be around for awhile. In contrast, EISA was tying you to the past by loading your system down with old cards that may not be good performers in the future.

Kildall asked for examples of how EISA would hold someone back. Rosch said any old 16-bit AT cards would not have 32-bit performance. You would still need to add new 32-bit cards into the computer to get 32-bit performance. If you had to buy new cards, why not buy a computer with a higher-performance standards like MCA?

Cheifet then turned to Hoyle and asked him to demonstrate his company’s computer, the CompuStar, which claimed to be “bus-switchable.” Hoyle noted that the industry was in a constant state of transition. Roughly every three years there had been a transition (8-to-16-to-32-bit). We were now about 18 months into the 32-bit Intel 80386 and were therefore likely to see the Intel 80486 or equivalent by the end of 1989, which would trigger yet another transition.

The idea behind the CompuStar, Hoyle continued, was that it was convertible. Users could change between processors and even bus architectures as their needs changed. Hoyle then opened up the large CompuStar PC tower sitting on the studio desk (with some assistance from Kildall) to reveal separate chambers containing the hard drive and the motherboard. The 80286 CPU came on a module that plugged into the motherboard. This could be exchanged for a 386 (or future 486) module. There were also separate bus modules supporting both MCA and ISA expansion slots.

Kildall asked Rosch if this sort of hybrid approach was the way to go. Rosch said it seemed to offer a better alternative than EISA because it didn’t restrict you to a particular architecture. So it may be the best of all possible worlds.

Cheifet asked if there was now confusion in the marketplace due to the bus battle. Rosch said that some people believed the bus battle was designed to create confusion in the marketplace. In talking to people, he found there was more skepticism than confusion. Some people didn’t think EISA would actually happen. Right now, there was an acceptable, high-performance standard in MCA that seemed like a good bet. And there was still a lot of life left in the AT bus for run-of-the-mill applications. EISA could fit in the middle or go to the high end, but it was impossible to know until we saw the actual machines.

The Real Winners Were the Expansion Cards We Installed Along the Way

When George Morrow and Howard Fullmer proposed the S-100 bus standard back in the late 1970s, one of their goals was to prevent Intel from asserting control over the future development of microcomputer architecture. Ironically, that’s exactly what happened as a result of the late 1980s “bus wars.” Neither IBM’s MCA nor the Gang of Nine’s EISA bus proved to be the answer in the long run. Instead, it was Intel’s PCI bus developed in the early 1990s that would become–and essentially remain–the PC standard for decades. (Even Apple eventually abandoned NuBus for PCI.) How that happened is a long story, one that friend of the blog Ernie Smith told quite well in a May 2024 guest article for the IEEE Spectrum.

As for MCA, it turned out to be a self-inflicted mortal wound to IBM’s PC business. In his 1993 book Big Blues: The Unmaking of IBM, Wall Street Journal reporter Paul Carroll detailed how IBM executives–in particular, entry systems division head Bill Lowe–bungled the entire strategy behind MCA. Lowe “decided that he needed to show the world just how serious he was about Micro Channel” by killing the PC-AT, IBM’s best selling computer, in order to force customers to buy new machines with MCA.

Lowe further believed that he’d set a clever trap for the clone-makers. IBM’s lawyers assured Lowe that existing AT clones violated several key IBM patents. As those machines had already been on the market for several years, it would have been difficult to pursue patent infringement lawsuits in the courts. But Lowe assumed that as the clone-makers rushed to copy the new MCA bus, he could force them to not only license the MCA patents but also pay IBM for the use of its older AT patents. To that end, IBM changed its licensing policy to require payment of a 5 percent royalty on every machine sold, as opposed to the prior rate of 1 percent.

Of course, it turned out nobody wanted to clone the MCA bus. More to the point, the customers weren’t clamoring for MCA machines. They were perfectly happy to either stick with their existing AT-bus machines or wait to buy a new PC with an Intel 80386 CPU. And Compaq and other clone-makers had already beat IBM to the market on the 386. But Lowe was convinced that he could effectively conjure demand out of thin air by talking up the MCA’s technical specs.

You can actually see part of IBM’s disconnect in this episode. I largely glossed over Chet Heath’s demonstration because all he did was show Stewart and Gary some in-house benchmark tests used to measure hypothetical performance. Contrast this with Bob Kutnick–who didn’t actually have a product to demonstrate–explaining the potential benefits of EISA by showing how it would affect the speed at which end-user applications ran in real time.

Paul Carroll clearly saw the same thing at the time, noting that nobody outside of IBM cared about benchmarks:

Customers only cared about how fast a PC was when it came to real-world applications, such as recalculating a spreadsheet, and customers understood that the only significant difference between IBM’s machines and competitors’ swas that IBM wanted a 30 to 50 percent price premium.

Ultimately, MCA only managed to accelerate IBM’s decline as the PC industry leader. In fact, just a few weeks after this episode aired, Lowe resigned from IBM and joined Xerox as an executive vice president. Ken Maize, writing for NewsBytes, said that Lowe “was not forced out at IBM, but apparently left because his career had hit the doldrums” due in part to his “decision to abandon the AT bus to the clones.”

Wells American Horror Story

William M. Wells III formed Intertec Data Systems Corporation in May 1973. Wells was an electrical engineer who previously worked at IBM’s research department in Gaithersburg, Maryland. While at IBM, he developed a microprocessor-based video terminal. When IBM decided not to manufacture Wells’ terminal, he borrowed $1,000 to start Intertec.

Wells later took on a partner, Edward O. Caughman, and they moved the company twice, first in 1974 from Maryland to Charlotte, North Carolina; and then in 1978 to Wells’ hometown of Columbia, South Carolina. It was also in 1978 that Intertec expanded from manufacturing terminals into producing fully assembled microcomputers. Intertec’s first micro was the SuperBrain, a Zilog Z-80-based single-user computer running Gary Kildall’s CP/M operating system. Two years later, in 1980, Intertec released the CompuStar, a $5,000 multi-user system that could connect up to 255 terminals costing $2,500 each.

Intertec’s sales grew from $568,000 to $17.156 million between 1976 and 1981, with the company reporting a healthy $3.731 million profit in 1981. Not coincidentally, Intertec also went public in 1981, raising $17 million in its initial offering on the American Stock Exchange.

Unfortunately, just as George Morrow and Howard Fullmer learned, Intertec saw sales of CP/M-based systems start to crater after IBM introduced the PC at the end of 1981. In July 1983, Intertec reported a fourth quarter loss of about $675,000, and while the overall fiscal year was still profitable, net income declined from $27.3 million in 1982 to just $1.2 million in 1983. This forced Intertec to lay off about one-third of its workforce–120 people–and Wells forfeited his $200,000 salary for the year. (He still owned about 44 percent of the company.)

Wells’ plan to transition Intertec into this new PC era was to create a computer that was both a floor wax and a dessert topping. In November 1983, Intertec announced its first new computer model in three years, the HeadStart, which included both a Z-80 and an Intel 8086, so it could run 8-bit CP/M and 16-bit MS-DOS programs. Intertec further advertised the HeadStart as both a single-user and multi-user computer, claiming it was possible to network up to 255 machines to a single 50 MB hard disk drive.

While it may have sounded great in theory, the HeadStart proved a disaster in practice. In July 1984, Intertec suddenly laid off about 90 more employees, giving them only 15 minutes notice. One fired sales staff member told the Columbia Record that the company had only managed to ship 24 HeadStart computers to retailers–and 8 of them were returned due to “hardware problems.” Meanwhile, orders continued to pile up but could not be fulfilled due to lack of inventory.

The anonymous sales staffer went on to say that retailer demand for the HeadStart was non-existent because Intertec had yet to complete the promised networking software or hard disk drive, both of which were needed to operate a multi-user system. And while the HeadStart was designed to run as a single-user computer, the suggested retail price was $3,495, which made it a non-starter in a market where you could buy, say, a complete Apple IIe system for about $2,000.

Things quickly went from bad to worse following the HeadStart debacle. In March 1985, the company reported $14 million in losses on just $3 million in sales. Intertec laid off all but 12 employees. Wells shut down all production and marketing operations and kept just administration and research and development going.

In a last-ditch effort to save the business–and presumably shed its tarnished reputation–Wells decided to change the name of the company from Intertec Data Systems Corporation to Wells American Corporation in September 1985. Wells also ceded day-to-day control of the company to his brother, Ron Wells, who held the title of president. Ron Wells said the new plan was to create a computer that Wells American could sell to large corporate customers who wanted to buy less-expensive PC compatibles in bulk.

In response, one understandably irate shareholder told the The State newspaper in Columbia, “I don’t think they’ve learned from the past that you can’t complete with the likes of IBM and it looks like they’re going to try again. By the time [Wells] develops something and comes out with it, there’s going to be something new.”

Shareholder skepticism notwithstanding, the newly rechristened Wells American managed to restart its manufacturing operations in March 1986 and produce a new PC-AT Compatible, the A-Star, which sold for $1,695. Ron Wells told the press that unlike the HeadStart, the A-Star came with all of the necessary multi-user and networking circuitry out of the box. Wells also said the company would no longer go through retailers, instead selling the A-Star “factory direct” to business customers and “private label” resellers who re-branded the computer with their own names.

Initially, the turnaround seemed to be working. In June 1987, Wells American still reported an annual loss, but it was just $359,000, as opposed to the $3.57 million loss reported in 1986 (and the $14 million loss in 1985). The following July, Wells American finally returned to profitability, posting net income for the 1988 fiscal year of $100,000 on $15.8 million in sales.

Building on the A-Star’s success, Ron Wells announced the company’s next new computer in July 1988, the CompuStar, which revived the name of Intertec’s earlier multi-user computer from the CP/M days. As we saw in this episode, the CompuStar’s main feature was that it could be reconfigured to support multiple bus architectures. William Wells told The State the new CompuStar “solves the users’ dilemma of having to chose between competing design architectures.” But Michael Hoyle, the product manager seen in this episode, later said that customers only ordered machines with the ISA bus as MCA “was a flop.” Wells American also released a smaller machine called the CompuStar II that only came with the ISA bus.

Now, the CompuStar wasn’t cheap. The standard configuration sold for $4,650. But this was a machine targeting corporate customers looking to buy in bulk. A February 1989 review in InfoWorld praised the CompuStar’s “incredible workmanship” and the ease of servicing and swapping out parts within the system, which overall made “its value good.”

But good reviews don’t necessarily translate into strong sales. Less than a year after Wells American started shipping the CompuStar, the company was back in the red. Once again, the company had to severely curtail its operations, suspending most manufacturing and marketing activities in January 1990. Bizarrely, Ron Wells blamed the cutbacks on a dispute with computer magazine publisher Ziff Davis, whom he claimed wasn’t accepting the company’s ads due to a billing dispute. (Ziff Davis said Wells refused to pay for ads that were rejected for failing to meet the magazine’s standards.)

Shortly thereafter, in March 1990, William Wells resigned as chairman of Wells American. Ron Wells succeeded his brother as chairman and appointed Robert K. King as the new president. The younger Wells and King then unveiled yet another plan in May to try and save the company: Creating a subsidiary, NewCo Technology Inc., to develop Apple Macintosh-compatible products. But as The State reported, “No one at Wells American would comment on specific products that NewCo will make.”

To fund NewCo, Wells American decided to hold a garage sale–well, an auction of various “computer parts, business and manufacturing equipment, and office furniture,” according to The State. The auction raised about $105,000. While not a bad haul for a garage sale, it didn’t do much to put a dent in the $7.1 million loss Wells American posted for 1990.

In July, Robert King told The State that Wells American was “studying mergers and other ways to boost capital in an effort to regain profitability.” He was also still committed to producing products for the Macintosh. But he still wouldn’t tell the press what those products were.

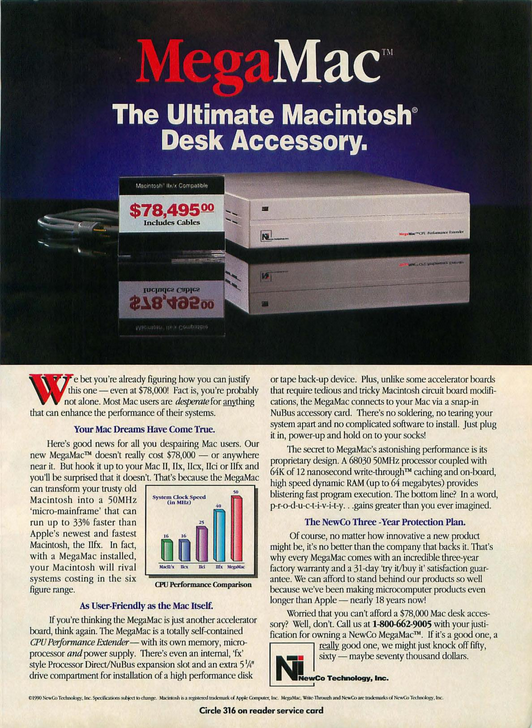

The answer finally came in the August 1990 issue of MacWorld, where NewCo Technology took out a full-page ad to announce its first Apple product–the MegaMac. Billed as “The Ultimate Macintosh Desk Accessory,” MegaMac was a 50 MHz Motorola 68030 CPU add-on board that plugged into the NuBus of any Macintosh II. NewCo’s ad (see below) claimed this would enable older Mac II machines to run 33 percent faster than Apple’s then-newest machine, the Macintosh IIfx.

The real head-scratcher was the advertised price of the MegaMac: $78,495. Of course, that wasn’t the real price. The text of the ad said NewCo would “knock off” $70,000 if you actually bought one, making the real price a still-ludicrous $8,495. The five-figure fake price was simply meant to show how “Mac users are desperate for anything that can enhance the performance of their systems.” (I’m starting to see why Ziff Davis refused to accept Wells American’s ads.)

In reality, it was Wells American that was desperate for anything that could enhance their collapsing balance sheet. A couple of weeks after that Macworld issue hit the newsstands, Wells American held a second garage sale–er, auction–because they still didn’t have sufficient capital to actually manufacture the MegaMac. At this point, the company effectively had no products to sell, having abandoned their PC business in January 1990. For the quarter ending June 30, 1990, Wells American reported just $64,260 in sales–down from $2.55 million in the comparable quarter of 1989.

In December 1990, the American Stock Exchange de-listed Wells American’s common stock, citing its “inability to meet guidelines for listing.” At that point, company officials admitted they were now facing the prospect of either liquidation or reorganization in bankruptcy. Ultimately, they opted to go with liquidation. On May 2, 1991, Ron Wells announced that Wells American had filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

Michael Hoyle ended up purchasing most of Wells American’s remaining CompuStar inventory from the bankruptcy court. Hoyle, who joined Wells American when it was still Intertec back in 1982, created a new company, CornerStone Technologies, Inc., which also took over servicing existing CompuStar and A-Star customers. Hoyle told The State he wasn’t sure exactly how many Wells American machines were still in use, but the company’s customer list had about 25,000 names. Hoyle continued to run CornerStone until dissolving the company in 1996.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was first broadcast during the week of November 15, 1988.

- Bob Kutnick worked as a chief technology officer for a number of startup companies from the 1990s through the 2010s, most recently as a senior vice president with Florida-based Citrix Systems. In 2017, he co-founded Minds Untapped, a company that develops a mobile app to assist “families and individuals affected by autism who require support.”

- Richard Archuleta remained with Hewlett-Packard until 2006, eventually becoming a senior vice president. He then joined Plastic Logic, a European tech startup that developed flexible display technology for e-readers. Archuleta retired in 2022 following a brief stint as CEO of a cloud computing company.

- Chet Heath spent 30 years at IBM. In 2000, he joined Omnicluster Inc., a Florida-based startup spun off from IBM, as its chief technology officer. Omnicluster originally manufactured server blades–single-function computer cards that plug into servers–but later pivoted to network security appliances. The company renamed itself 14 South Networks in 2003. Heath left the company in 2004. Since 2008, he’s been affiliated with the Quantum Group, Inc., a Florida-based healthcare technology company run by Pete Martinez, who worked with Heath at IBM.

- Winn Rosch has been a computer journalist since the early 1980s, including extended stints as a contributing editor at PC Magazine and a technology reporter and columnist with the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Rosch is also a licensed attorney.

- Mark Orr left Apple in 1996, joining former colleagues Vivek Mehra and Mark Wu to start Cobalt Microserver, which developed low-cost Linux server appliances. Sun Microsystems purchased Cobalt for $2.1 billion in 2001.

- This episode aired just after the 1988 United States presidential election. Apple CEO John Sculley told the press that he reluctantly voted for Vice President George H.W. Bush as the lesser of two evils, lamenting that neither the Republican nor his Democratic opponent, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, offered “a vision for the 1990s.” In the end, Sculley said Bush was “more predictable,” although Republican vice-presidential candidate Dan Quayle was “a disappointment.” Incidentally, just after the election, Sculley sold about one-third of his Apple stock, netting about $2.1 million.