Computer Chronicles Revisited 110 — Draw Applause, EnerGraphics, Freelance Plus, and Harvard Graphics

Perhaps IBM’s most important contribution to the development of the personal computer was pushing graphics standards forward. Early microcomputers tended to output only text characters. And those machines that did implement some form of bitmap graphics, such as Steve Wozniak’s Apple II, did so without any eye towards establishing an industry-wide standard.

That changed with the introduction of the Intel 8088-based IBM Personal Computer in 1981. IBM developed two graphics cards–the Monochrome Display Adapter and the Color Graphics Adapter (CGA)–for use with its PC. The CGA card could output 16-color bitmap graphics with a resolution of 160-by-100 pixels, although in practice most programs used a higher-resolution 320-by-200 mode that only displayed 4 colors.

Three years later, in 1984, IBM introduced the Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA) to go with its Intel 20286-based PC/AT models. EGA offered a resolution of 640-by-350 and the ability to display up to 16 colors at once (out of a palette of 64). Three years after that, in 1987, IBM replaced EGA with the Video Graphics Array (VGA) standard, which was a key component of the company’s new 80386-based PS/2 line and increased the maximum possible resolution to 640-by-480, as well as a 256-color mode at 320-by-200.

As IBM continued to up the ante with its graphics cards–and the PC clone-makers followed suit–demand for business graphics software increased accordingly. By April 1988, when this next Computer Chronicles episode aired, the Macintosh’s early advantage in high-resolution graphics had evaporated, and the PC was now more than capable of producing the bar graphs and pie charts demanded by middle managers throughout the Fortune 500.

This was the second in a two-part series on computer graphics, with the previous episode focusing on Macintosh applications. For this episode, Stewart Cheifet opened by showing Gary Kildall two binders. Each binder contained identical sales reports, except that one featured business graphics produced with software from Kildall’s company, Digital Research, Inc., and the other did not.

Cheifet noted that when you thought about business graphics, you typically thought about the Macintosh. But from the perspective of a new user looking to get into business graphics, did it matter if they used a Mac or an MS-DOS machine? Kildall said it really didn’t matter. The Macintosh offered a standard environment–any Mac you bought would have the same high-resolution graphics. (Of course, only the Macintosh II offered color.) On the IBM PC, in contrast, you would have to configure the system, either by yourself or through a dealer, when it came to having an EGA or VGA graphics card at the resolution you wanted. But once you got there, you’d then have access to a number of software options.

Digital Research Powers Defense Contractor’s Manuals

Speaking of Digital Research’s graphics software, that was the subject of Wendy Woods’ first remote segment. Woods reported from the Sunnyvale, California, offices of ESL Incorporated, a subsidiary of the defense contractor TRW Inc., which specialized in producing communications and reconnaissance equipment for the military. The production of technical and maintenance manuals for that equipment used to require the cooperation of a group of departments, Woods said, as well as an outside print shop. But today, most of that work was now done by one person working on a single PC, from drawing the illustrations to writing the text and designing the layout.

Henry V. Walker, a logistics engineer with ESL, explained to Woods that when it came to something like producing a single book, the person assigned to manage that project traditionally had to keep track of the illustration department, technical writers, and other external groups. With an all-in-one software package, however, they didn’t need to keep track of all of those people. The project manager could now sit, decide on any changes that were needed, and make them right away with the software.

Woods said ESL’s manuals were now designed using Digital Research’s GEM Presentation Package. This included GEM Draw, which handled the technical illustrations; GEM Graph, which produced the charts and graphs; and GEM Desktop Publisher, which combined the graphics and illustrations with text.

Assembling all of the elements of a manual was still not completely solved, Woods said, due to the mixture of Macintosh and IBM PC hardware at ESL’s offices. This limited the types of files that could be transferred over a local area network. And the actual printing of the manuals was still handled out of house. But Walker said he was still pleased with the progress so far. He told Woods that the computer still couldn’t do the drawing for you, but it could sure help. He reiterated that the main benefit of the computer was that it gave you an immediate end result.

Ashton-Tate vs. Enertronics Research

Richard Dym and Randy Andes joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first studio segment. Dym was a senior product manager with Ashton-Tate. Andes was vice president of marketing with Enertronics Research.

Kildall opened by noting that when the first IBM PC came out in 1981, it still primarily relied on a text character-based display. Was there now a movement towards IBM PC users demanding more when it came to graphics? Dym said yes. He credited the success of the Macintosh’s graphical user interface–and more recently, IBM’s adoption of Presentation Manager for the PS/2–as providing a more optimum and easy-to-use interface for business users.

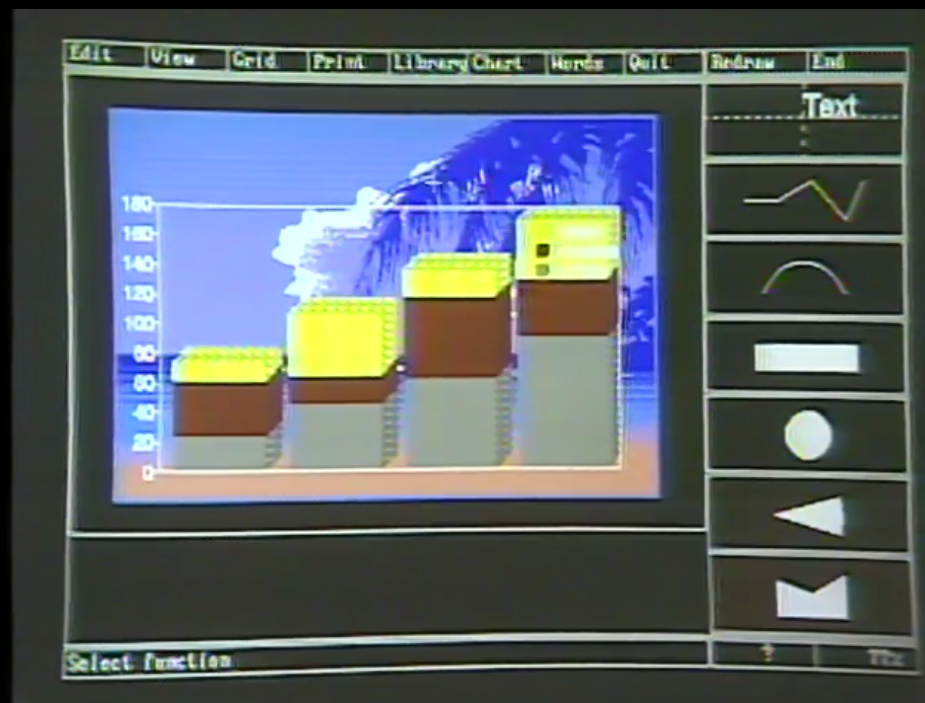

Moving into the demo, Kildall quipped that Ashton-Tate, a database software publisher, wasn’t exactly known as a business graphics company. Yet the on-set demo of Ashton-Tate’s newest product showed a background image of a beach. Dym said the product, Draw Applause, released in January 1988, combined a powerful drawing board with a strong business graphics capability.

Draw Applause relied on a series of menus along the top of the drawing board together with a set of drawing tools accessible on the right side of the screen. Dym explained that a user could directly import data into Draw Applause from Ashton-Tate’s dBase III. He demonstrated by retrieving a file, which the program then used to automatically produce a bar graph on the screen. The user could easily change the type of chart, which Dym did by changing the bar graph to a pie chart. Dym then showed off the various options you could set within the chart, such as making a bar graph 3D.

Dym added that while he was using a mouse and keyboard for this demo, Draw Applause also supported the use of a graphics tablet.

Next, Dym imported that image of the beach Kildall referenced as a background. This was one of 125 background images that came with Draw Applause. Dym then placed his previously created chart on top of the beach background. After making some final adjustments and adding text, Dym showed off his finished slide (see below).

Kildall noted that this demo ran on a Tandy 4000–a 386 PC–which was why the program ran so fast. Dym clarified that Draw Applause would run on an older 8088- or 8086-based PC. Of course, it moved along much quicker on a 386.

Reviving his favorite follow-up question from the prior episode, Kildall asked Dym about the options for producing hard copy with Draw Applause. Dym said the software supported a full range of black-and-white devices, such as dot-matrix and laser printers, as well as flatbed plotters. Ashton-Tate had also launched the Ashton-Tate Graphics Service. With this service, someone could send an image to Ashton-Tate using Draw Applause’s built-in communications software and receive a finished slide back the next day in the mail.

Cheifet asked Dym if a user could import files into Draw Applause from programs other than dBase III? Dym said yes, it accepted worksheets from Lotus 1-2-3 as well as files using the open Computer Graphics Metafile (CGM) standard.

Turning to Andes, Cheifet asked for an explanation of what his company’s product, EnerGraphics, did. Andes said that in addition to the type of drawing board you saw with a program like Draw Applause, EnerGraphics also had a full charting capability. It could do 2D charts in about 35 or 40 formats, as well as 3D charts and analytics.

Cheifet asked for a demo. Andes showed off what he called an add-on product for his company’s EnerGraphics package, which specifically accentuated its 3D graphics capabilities. Andes noted a user can import chart data from a Lotus spreadsheet using a built-in macro.

The demo itself featured an image of a raised 3D pie chart in color. Andes showed how you could change a chart’s settings, such as rotating the image, in a “draft” mode. He added the program could also handle mapping. For example, you could take a 3D map of the United States and select regional areas or individual states.

Kildall asked if EnerGraphics was an upmarket product that required sophisticated artistic abilities to use. Andes said EnerGraphics was a powerful and flexible program, but they tried not to ignore the new person looking to get into the graphics world. Through prompts and menus, novice users could create nice-looking charts, and they could grow with the program. But he acknowledged that EnerGraphics was focused on the power user, similar to WordPerfect for word processing.

San Francisco Fed Pivots to Video

For her second and final remote segment, Wendy Woods reported from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which used the PictureMaker system from Cubicomp Corporation to produce an educational video, How Banks Create Money, designed to teach high school students.

Woods noted the animated video wasn’t made at a high-tech production house in Los Angeles, but rather at the Fed itself. The San Francisco office maintained roughly $100,000 in sophisticated computer graphics design gear, along with a full-time team assigned to produce animation. And why did the Fed need animation? As part of the federal government, the Fed saw these videos as part of its role in educating students about finance.

Bill Rosenthal, a graphics designer with the San Francisco office, told Woods that the “MTV generation” was used to this type of communication, and old-fashioned videotapes were not as interesting to today’s students.

Woods added that the Fed’s in-house graphics team also produced thousands of slides for the Bank’s business meetings. But it was only a matter of time before computer animation was as in-demand as the slides. Indeed, over the past year the computer graphics team’s work had quadrupled, a trend being echoed throughout the big business community.

Lotus vs. Software Publishing

For the final studio segment, Tim Davneport and Tess Reynolds joined Cheifet and Kildall in the San Mateo studio. Davenport was the director of the graphics products division at Lotus Development Corporation. Reynolds was a group product manager with Software Publishing Corporation.

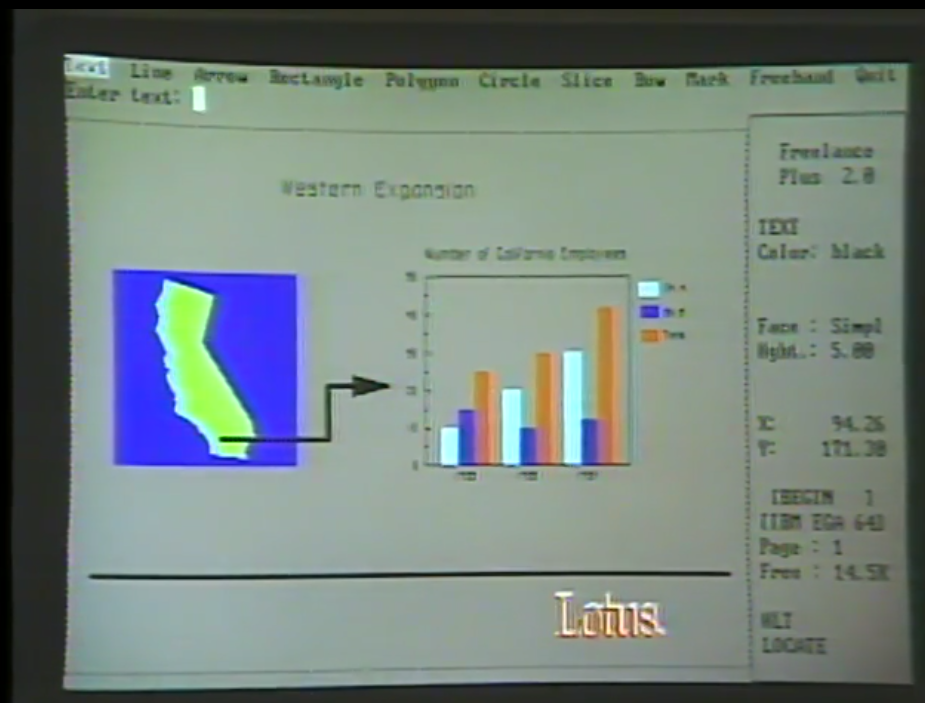

Kildall noted that Lotus 1-2-3 was a very popular program, but its graphics feature was widely considered difficult to use. Did Lotus’ new business graphics package, Freelance Plus, correct that? Davenport pushed back on the notion that 1-2-3’s graphics were difficult to use, but he said customers wanted to do more when it came to charts. Freelance Plus was therefore introduced to either enhance the charts created in 1-2-3 or to create such graphics from scratch.

Davenport then launched into his Freelance Plus demo. He created a bar chart directly in the program, which he then formatted into a slide. On the right side of the screen was a status panel. The user could also use a second “page” as a scratch pad. Davenport pulled up this second page, which he used to display a map of the United States, one of 500 built-in images that came with the program. He selected California and copied it to the slide on the first page. To complete the demo, Davenport added some additional lines and shapes (see below).

Kildall noted that Davenport used the keyboard for his demo, but Freelance Plus also supported a mouse. And yet again, Kildall asked about the types of output devices supported by the program. Davenport said Freelance Plus supported a range of pen plotters and color inkjet printers.

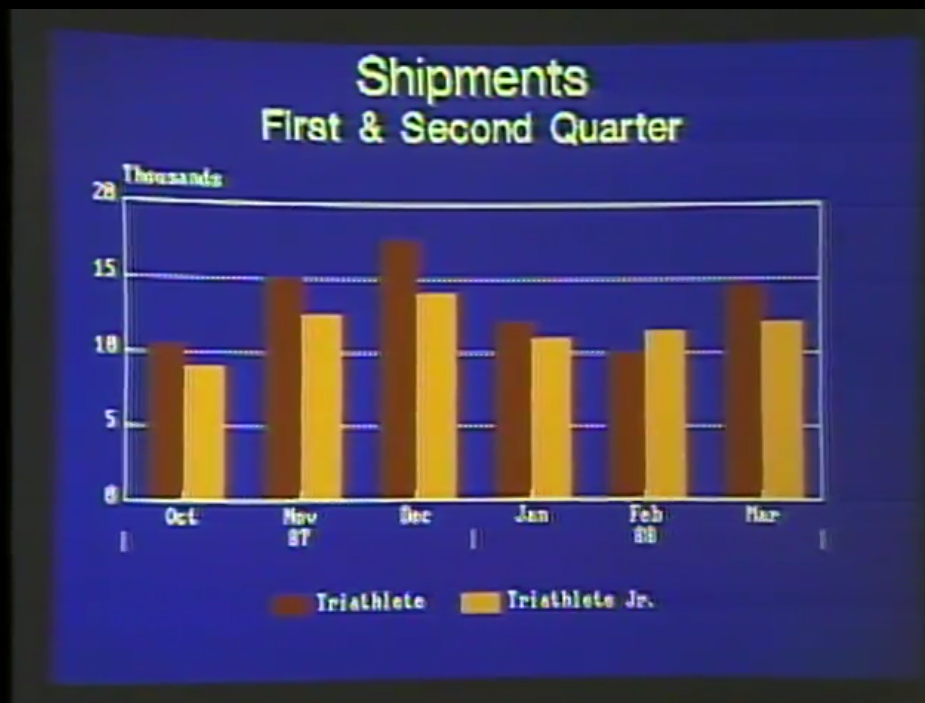

Turning to Reynolds, Cheifet noted that Software Publishing took a different approach with its program, Harvard Graphics. Reynolds said unlike Freelance, Harvard Graphics focused on the charting and text generation features of creating a presentation. Her demo started with a simple bar chart (see below), which the program generated automatically after the user entered their data. This output could be sent directly to a plotter or other output device. But if the user wanted to change any of the defaults, such as the colors of the bars, they could press F8 and pull up a detailed options screen.

Reynolds continued, explaining that pressing F4 brought up a data editor with 18 built-in formulas. Hitting F2 then redrew the graph.

Cheifet noted that Harvard Graphics made it possible to use the computer itself to run a demonstration, as opposed to converting the images into physical slides. Reynolds showed how that worked. There was a “slide show” option in the program’s main menu, which enabled a large-screen monitor or other EGA-capable display to present a slide show that included transition effects. The user could then control the pace of the slide show using either a keyboard or mouse.

Finally, Cheifet asked if it was possible to import data from other programs into Harvard Graphics. Reynolds said yes, the program supported 1-2-3 spreadsheets and other leading programs. She also showed sample hardcopy output from Harvard Graphics to a color thermal printer.

The Graphics Software “Gold Rush”

Among three of the companies featured in this episode–Ashton-Tate, Lotus, and Software Publishing Corporation–there was something of a gold rush to enter the business graphics market in the mid-1980s. Although unlike the mid-19th century, when the California gold rush saw prospectors travel westward to seek their fortunes, here we had three West Coast companies looking eastward to acquire smaller firms that claimed to strike gold with their business presentation applications.

Indeed, the three products demonstrated by these companies in this episode all came about through acquisitions. The first such deal involved Software Publishing, which acquired Massachusetts-based Harvard Software–makers of what was originally called Harvard Business Graphics–in August 1985. (Harvard had no affiliation with the famous university; the company ’s first office was in the town of Harvard, Massachusetts.) The following year, in June 1986, Lotus acquired another Massachusetts company, Graphic Communications Incorporated, which published the original Freelance. Two months later, Ashton-Tate purchased Connecticut-based Decision Resources for $13 million in cash.

Unlike Lotus, which immediately closed Graphic Communications and absorbed its graphics software development into the company’s California headquarters, Ashton-Tate initially kept Decision Resources in New England as a subsidiary. Decision’s original business graphics packages, published under “Master” name (e.g., Chart-Master, Map-Master, etc.), eventually morphed into Draw Applause, which Ashton-Tate announced in January 1988.

Draw Applause, Freelance Plus, and Harvard Graphics all launched at a suggested retail price of $495. A September 1988 issue of PC Magazine had a roundup of the three programs along with several other competitors. Reviewer Craig Ellison noted that Draw Applause was “one of the two most-talked-about programs” at that year’s National Computer Graphics Association conference, finishing behind Zenographics’ Pixie–the bargain option at $195–by one vote for the crowd’s favorite business graphics application. Ellison himself said Draw Applause’s initial release delivered “an impressive performance” that far surpassed Decision Resources’ aging Chart-Master.

As for Lotus’ offering, PC Magazine’s Robin Raskin–a former Computer Chronicles guest–said, “If you had to pick one tool and use it for all of your graphics needs, Freelance Plus might be the ticket.” Raskin praised its integration with 1-2-3, the ability to easily edit objects, and the wide range of supported output devices. But she also critiqued the lack of any 3D graphing features as well as the fact that colors and fonts were “not displayed in true WYSIWYG fashion,” meaning the text you saw on the screen was only a “stick-figure approximation of the font’s height and width.”

Meanwhile, PC Magazine reviewer Robbin Juris heaped mostly praise on Harvard Graphics, concluding that Software Publisher’s successor to the original Harvard Presentation Graphics was “one of the most intelligently designed packages available” and made “creating charts and graphs an almost effortless enterprise.” Juris’ main criticism was the relative lack of clip art, with the included library featuring only about 300 images. (Of course, Software Publishing offered an additional clip art library for an extra $99.)

In terms of which of these programs was the most popular, PC Magazine surveyed 1,267 readers in May 1988 about their usage of business graphics software. Among those who responded, about 24 percent said they most often used Harvard Graphics at their company, with 14 percent saying Freelance Plus. Draw Applause had not been on the market long enough when PC Magazine conducted the survey, but about 7 percent of respondents said they most often used the earlier Ashton-Tate/Decision Resources graphics programs.

For its part, Software Publishing saw Freelance Plus as its main competitor. In a January 1988 business plan prepared by Tess Reynolds and her Harvard Graphics product team, they believed that Lotus had a 27 percent share of the business graphics market, followed by Ashton-Tate’s pre-Applause offerings at a combined 25 percent, and Harvard Graphics trailing at a distant 11 percent.

The Saga of Software Publishing Corporation

At this point, it’s worth taking a step back and looking at the history of Software Publishing Corporation (SPC), which was one of the more enigmatic business software companies of this time period. Indeed, while graphics software proved to be mere accessories to Ashton-Tate and Lotus’ respective core businesses, Harvard Graphics would eventually subsume SPC and become its main product.

SPC traces its roots back to Silicon Valley’s most venerable company, Hewlett-Packard. In the late 1970s, a young marketing executive in HP’s minicomputer division, Fred Gibbons, was considered a rising star in the company. So much so that Apple co-founder Steve Jobs tried to recruit Gibbons, offering him a job as marketing manager for the ill-fated Apple III computer.

Gibbons wisely turned Jobs down, citing his satisfaction at HP. But it got him interested in microcomputers, which were starting to take hold beyond the hobbyist community. Gibbons conducted his own market research and decided personal computers were going to be a much bigger deal in the years ahead. But HP management was not yet ready to get into that area.

So Gibbons decided to start his own company. He recruited an HP colleague, John Page, to write an easy-to-use database management system for Apple II users. Gibbons and Page pitched their idea to a former HP executive, Jack Melchor, who had become a venture capitalist. Melchor agreed to fund their new company.

As Gibbons was a marketer, he needed someone to handle operations, so he brought in yet another HP colleague, Jenelle Bedke, an engineering manager in the company’s terminals division. The trio of Gibbons, Page, and Bedke formally incorporated Software Publishing Corporation in April 1980.

Five months later, in September 1980, SPC started shipping Page’s finished database program, which was dubbed pfs:File. (The pfs stood for “personal filing system.”) A back page ad in the second issue of Softalk (see below), an Apple II-focused computer magazine, served as the unofficial public launch for the new company and pfs:File. Bedke later recalled that shortly after the magazine came out, she heard the phone ring while she was in her swimming pool. She rushed out to answer the call, which came from a computer store owner who had seen the ad and wanted to place what was SPC’s first order.

By June 1981, SPC launched a second product–pfs:Report–and the company had moved operations out of Badke’s house and into a proper office. That June also represented the company’s first $100,000 sales month. At the end of SPC’s first full fiscal year in September 1981, the company reported a profit of $96,000 on sales of $732,000.

Sales and profits rose substantially over the next three years, with revenues and net income reaching $23.4 million and $3.6 million, respectively, for the 1984 fiscal year. A key factor in this growth was Gibbons’ decision to sign a deal with IBM in May 1983 to create “private label” versions of SPC’s pfs software for the IBM PC, which Big Blue released under the “Assistant” brand name. For example, IBM’s version of pfs:File was called IBM Filing Assistant.

Now armed with a stable of seven products that had shipped a combined 750,000 units, Fred Gibbons decided to take SPC public in November 1984, raising approximately $10 million in additional capital.

Initially, the post-IPO period continued to be profitable for SPC. And now that he had some additional funds, Gibbons looked to expand the company, as he did with the purchase of Harvard Software in August 1985. Of course, this was also right around the time we saw a general slowdown in the personal computer industry. And SPC was not immune.

In particular, 1986 represented the company’s first real period of struggle. That January, Gibbons suffered a serious accident while skiing, which kept him out of commission for several weeks. In June, SPC reported its first-ever quarterly loss of $1.6 million. Meanwhile, sales of the original pfs product line for the Apple II started to crater, due in no small part to Apple’s decision to launch a competing office suite, AppleWorks, in 1984.

That said, the decline of the Apple II as a viable platform helped SPC to refocus. Co-founder John Page noted in a 2017 oral history interview that SPC had been trying to support too many platforms:

[W]e’d rapidly realized that the consumer model [for software] was more like [the] CD player and CDs. You know, the computer is the player…And so Fred was like, “We’ve got to be able to run on all of the popular players.” And I was like, “You don’t know what you’re saying when you say that!” But he insisted. He was the President. “Yes, sir, we’re going to make it run on those.” So we made a tremendous effort to produce CP/M versions and Apple II and Apple III [versions], and all this stuff.

Gibbons himself acknowledged in a 1986 interview with LOTUS magazine’s Paul Freiberger that he erred in trying to support every platform long after it became clear that “the world was going to go totally PC compatible.”

More to the point, Gibbons decided that SPC’s future was in targeting the more lucrative high-end business market as opposed to novice home users. The main appeal of the pfs series had been its pricing. At a time when a professional database manager like Ashton-Tate’s overly complicated dBase III would cost you $700 at retail, you could buy the easy-to-use pfs:File for around $140. SPC also relied heavily on discounts and trade-in promotions to drive sales. For instance, in the summer of 1985, a customer could trade-in their Lotus 1-2-3 disk to SPC and receive a copy of the spreadsheet pfs:Plan for just $20.

A year later, however, Gibbons decided to launch the PFS: Professional Series, which targeted advanced users and carried a higher price tag than the original pfs offerings. That was soon followed by Harvard Graphics, which retailed for $495, matching Lotus and Ashton-Tate’s pricing for its business graphics packages.

Ultimately, Harvard Graphics proved to be a winner. Paul Zucker, reviewing the program in 1989 for Wendy Woods’ NewsBytes, proclaimed that Harvard Gaphics was “justifiably THE graphics package against which all others are judged.” By 1991, sales of Harvard Graphics were so strong that Fred Gibbons decided to divest the company’s original product line, selling off the pfs series to Boston-based Spinnaker Software, which was in the midst of its own transition from publishing educational software to selling low-cost home productivity programs.

At this point, SPC was the Harvard Graphics company. Roughly 80 percent of SPC’s sales in the 1991 fiscal year came from Harvard Graphics–which had now been ported to Windows–and related presentation products. Still, the company reported a loss for the year of $18.1 million on $143.1 million in sales. And with the irreversible decline of the MS-DOS software market, Harvard Graphics started to rapidly lose market share, as Microsoft consolidated its hold on the business software market, including presentation graphics.

Notably, in November 1991, Microsoft offered a low-cost “upgrade” program to entice users of Harvard Graphics and other competing graphics packages to switch to PowerPoint. Taking a page out of Fred Gibbons’ old playbook, a Harvard Graphics user could turn in their original disk to Microsoft and receive PowerPoint for just $129. (The suggested retail price was $309.)

As the 1990s progressed, it became clear that the mass market for business graphics had shifted to PowerPoint. Consequently, SPC never managed to regain profitability. In the 1996 fiscal year, the company reported another loss on sales of just $31 million, a 78-percent decline in five years. In October 1996, SPC agreed to merge with Allegro New Media Inc., a Connecticut-based publisher of CD-ROM software. Under the all-stock transaction, SPC’s shareholders took 45 percent of the combined company. Allegro subsequently renamed itself Vizacom.

The Harvard Graphics line continued under the new regime, albeit largely as a legacy product. In 2001, VIzacom licensed the exclusive marketing rights to Serif Incorporated. Serif was another company that previously merged with Allegro, but Serif’s management ended up buying itself back from Vizacom. As part of that deal, Serif continued marketing Harvard Graphics 98, the last version of the original program for Windows, and several other graphics programs still using the Harvard Graphics branding until 2017, at which point Serif shifted its focus to developing its “Affinity” line of graphics software products.

No Applause for Ashton-Tate; Lotus No Longer Freelance

I’ll briefly wrap up the stories of Ashton-Tate and Lotus’ business graphics products, neither of which enjoyed the same level of success as Harvard Graphics.

Ashton-Tate’s Draw Applause was largely marketed as a front-end for the company’s slides-by-mail Graphics Service, which was actually provided by a third-party company. Ashton-Tate did release a 2.0 version–Applause II–in February 1990. The following year, Borland International purchased Ashton-Tate in what turned out to be a disastrous deal. Development of Applause II, which remained a DOS-only application, effectively stopped at that point, although I found ads continuing to sell the program under the Borland label as late as 1994.

Lotus’ Freelance Plus fared somewhat better, eventually receiving separate releases for both IBM’s OS/2 and Microsoft Windows under the name Lotus Freelance Graphics. In 1992, Lotus incorporated Freelance Graphics for Windows and OS/2 into its integrated software package SmartSuite. IBM acquired Lotus Development Corporation in 1995, and continued to publish Freelance Graphics as part of SmartSuite. Active development of Freelance Graphics apparently ended in 2002, although IBM continued to support SmartSuite itself until 2013.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This program is available at the Internet Archive and was likely first broadcast around April 17, 1988. The recording on the Archive is a rerun from August 1988.

- Paul Schindler’s software review for this episode was Focal Point (Activision, $100), a HyperCard-based personal information organizer for the Macintosh. I previously covered the history of Focal Point on the blog and the podcast.

- Gary Kildall’s persistent questions about the hardcopy produced by his competitors’ graphics packages may have been a subtle boast about his own company’s GEM Presentation Pack. In his review, PC Magazine’s Robert Kendall noted, “In most cases, you can rest assured that the high quality of the graphics you create on-screen with the Presentation Pack will be matched in your hard-copy output.” One exception was 3D graphs, which had to be converted to 2D before being output to a plotter.

- Tess Reynolds remained with Software Publishing Corporation until 1992, when she left to start her own tech consulting firm. In 2003, Reynolds shifted to the nonprofit sector for what she described as personal reasons–her 8-year-old son died from cancer in 2000–and she became CEO of New Door Ventures, a San Francisco-based charity that provides employment and educational opportunities for at-risk teenagers and young adults. In 2020, Reynolds left New Door Ventures after nearly 17 years as CEO and returned to consulting, this time focusing on nonprofits and philanthropy.

- Richard Dym left Ashton-Tate in 1991 for a two-year stint at AutoDesk as general manager of its multimedia business unit. He went on to hold senior marketing roles for a number of tech companies through the 2010s, in more recent years focused on cloud software services.

- Tim Davenport joined Decision Resources as its general manager in 1981. After Lotus acquired Decision Resources, Davenport remained with Lotus as general manager of its graphics division until 1995. Since leaving Lotus, Davenport has been the CEO of more than a half dozen companies, mostly in the health care technology field. Since 2014, he’s worked as a consultant for cloud computing companies.

- F. Stephen Andes III and Douglas W. Wang founded Enertronics Research in 1981. (Randy Andes, the vice president of marketing who appeared in this episode, is Stephen’s twin brother.) Andes and Wang previously worked together at a St. Louis-based energy company, where Wang designed a portable energy cost calculator for home appliances. This became Enertronics’ first product. By 1984, however, the company shifted focus to its business graphics program EnerGraphics. Enertronics Research itself shut down in late 1994.

- Randy Andes left his brother’s company in 1989 to join Dell as a senior marketing manager. He remained at Dell for the next 14 years. Since 2007, Andes has worked in the long-term care insurance business.

- During the EnerGraphics demonstration, Stewart Cheifet and Randy Andes both referred to the add-on module as KaleidaChart. I could find no record of such a program. They may have been referring to KaleidaGraph, a program that has been published since 1988 by Synergy Software.

- Cubicomp Corporation’s PictureMaker system, which included software and a specially configured AT-compatible PC, cost $50,000, according to a 1986 article in InfoWorld. So it wasn’t exactly a mass market product. Indeed, the company boasted in a 1987 ad in Computer Graphics World that it had installed about 500 systems worldwide. Cubicomp itself proved to be a short-lived company. It started business in 1984 and filed for bankruptcy sometime in 1989 or 1990.

- Joe Armstrong and William J. Perry founded Electronmagnetic Systems Laboratory–later known as ESL Incorporated–in 1964. Perry, who later served as secretary of defense under President Bill Clinton, was the company’s president until 1977, when he left to take a position in President Jimmy Carter’s defense department. Shortly after Perry’s departure, TRW, Inc., acquired ESL in a stock swap. ESL continued to operate as a subsidiary of TRW until 2002, when Northrop Grumman acquired TRW. Northrop Grumman subsequently absorbed ESL into its space systems division in 2005.

- About two months before this episode first aired, there was a mass shooting at the ESL Incorporated offices in Sunnyvale, California. A former employee, fired three years earlier for stalking and threatening a female co-worker, armed himself with four guns and stormed the facility on the afternoon of February 17, 1988. The man proceeded to kill 7 people and injure 5 others, including the woman he stalked. He later surrendered to local police after a six-hour standoff. A California jury sentenced the killer to death in 1991. He remains on death row as of this writing, however, due to California Governor Gavin Newsom’s 2019 executive order imposing a moratorium on executions. In August 2024, the Santa Clara district attorney filed a motion in California Superior Court to officially change the killer’s sentence to life in prison. A hearing on that motion is scheduled for March 2025.