Computer Chronicles Revisited 103 — Photon Video Cel Animator, Music-X, and Video Toaster

In February 1987, Compute! magazine published the first hands-on look at the Amiga 2000. Released just 18 months after the original Amiga, Commodore International’s new model was a spec bump rather than a next-generation computer. Still, Compute! assistant editor Philip I. Nelson seemed duly impressed. He praised the 2000’s low price ($1,500 without a monitor) and the presence of multiple IBM PC-compatible expansion slots. Commodore even offered an optional “Bridge” card enabling the Amiga 2000 to directly run PC software. Nelson saw this as critical for attracting “professionals who bring their work home.”

Commodore formally debuted the Amiga 2000 in March 1987 at a computer show in West Germany. But this was not the only new Amiga announced. Commodore also released the Amiga 500, which targeted home users and initially retailed in the United States for around $700. (The original Amiga was retroactively renamed the Amiga 1000.)

The new Amigas came at a critical juncture for Commodore. Under co-founder and former CEO Jack Tramiel, Commodore fueled the boom for low-cost home computers in the early 1980s with the VIC-20 and the Commodore 64. Tramiel’s aggressive price cutting managed to drive his rivals out of the market. But it exacted an enormous toll on Commodore as well. After Commodore chairman Irving Gould ousted Tramiel in January 1984, the company struggled to stabilize its management and move beyond the success of the Commodore 64. This led to Commodore buying Amiga Corporation, which had been trying to develop a home video game console system, and essentially repurposing the Amiga prototype into the Amiga 1000.

By the time Commodore unveiled the Amiga 2000 and Amiga 500, the company had reported profits for three consecutive quarters–a solid turnaround after posting a $114 million loss in June 1985. But this return to black could largely be attributed aggressive cost-cutting rather than higher sales volume. So the question was whether or not the new Amigas could actually propel Commodore to the next level, particularly with respect to multimedia applications.

Was the Amiga Finally Getting Respect?

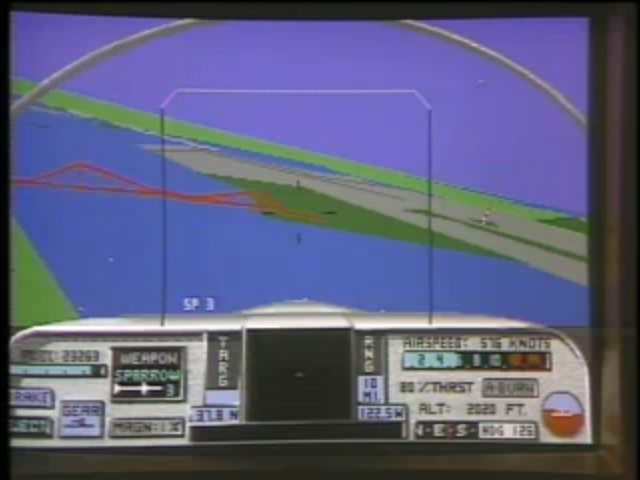

This next Computer Chronicles episode from late January 1988 came nearly a year after the debut of the new Amigas. Stewart Cheifet and Gary Kildall opened the program looking at a demo of F/A-18 Interceptor (see below), a flight simulator game published by Electronic Arts for the Amiga. Cheifet noted the graphics and sound were spectacular. Indeed, when you talked about the Amiga, one tended to focus on graphics and sound. Overall, Cheifet said the Amiga was a pretty good personal computer but, like Rodney Dangerfield, it got “no respect” among the IBMs and Macs on the world. Why was that?

Kildall said part of the reason was the Amiga’s Commodore heritage. The Commodore brand was associated with low-end computers. When the Amiga 1000 first came out, it was pitted against the Atari 520ST (produced by Jack Tramiel’s Atari Corporation), which cost $1,000 less than the Amiga. So the Amiga couldn’t compete on the low end. And moving upmarket was difficult because Commodore wasn’t established in those distribution channels. The Amiga platform also lacked the software base to compete with IBM and Apple. But now we were starting to see some really good software written for the Amiga, so that situation might change.

Photographer Bullish on Amiga’s Future

Wendy Woods presented the first of her two remote segments. This report focused on Larry Keenan, a San Francisco-based professional photographer and designer who used the Amiga as part of his business. Woods said that Keenan had added the Amiga to his collection of photographic equipment. Working with a video camera, a digitizer, and a software package called DigiView, Keenan could create new images directly on screen.

Keenan told Woods the Amiga-based system was a logical extension of his business. Because he worked with a lot of different elements in photos, the digitizing process was just like another brush or technique. It allowed him to take a photograph from a stock file, resize it, and take out elements. For example, say you had a favorite photograph with telephone lines or fences in the background. You could go in and digitize those things out.

Woods said that Keenan was well known for his work in advertising and magazine covers, and more recently for artwork used to decorate software packages. The computer gave him a definite advantage in dealing with the deadlines imposed by commercial work, and it let him be more independent. Keenan said the technology enabled anyone who was self-employed in the art field–artists, photographers, illustrators, et al.–to take an image, digitize it on their own terms, and present it, as opposed to relying on a technician to do that work.

But making the switch from a sharp lens to a fuzzy monitor was not without its problems, Woods noted. Keenan regretted the low resolution of a computer screen compared to photographic film. (The standard Amigas of this time period had a maximum graphics resolution of 640-by-400 pixels.) And Keenan found it hard to keep up with the constant changes to the technology. That said, he was optimistic, noting the trick was to learn the process, because that won’t change in the future, only the quality.

Producing Full-Color Animation at Home

Heidi Turnipseed and Adams Douglas joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Turnipseed was an animator with Five Rings Company. Douglas was director of product development with Microillusions, Inc. Kildall opened by noting that Turnipseed now used computers to help with her use of classical animation techniques. Why did she choose an Amiga over an IBM PC or Mac? Turnipseed said the Amiga was advertised as having full animation capability, including four-channel sound and a palette of 4,096 colors. That, combined with the Amiga’s reasonable price, were key factors in her decision.

Kildall asked Turnipseed to demonstrate her animation technique using Photon Video Cel Animator, a software package published by Microillusions. Turnipseed showed a pencil test she created in the software, a cycle of a galloping horse containing 10 separate drawings. She said she could test the animation at home, alter the drawings, re-digitize them, and save them back to disk until they were polished. Kildall clarified the drawings were done externally and not on the computer itself. Turnipseed said that was correct.

Cheifet asked about the next step in the animation process. Turnipseed said she animated a rider on a separate level, digitized that, mapped it onto the galloping horse frames, and saved them separately so she could always go back to edit one alone. Then she called up the pencil drawings in a paint program to color them.

Turning to Douglas, Cheifet asked about the actual software Turnipseed used. Douglas said it was the Cel Animator module of Microillusions’ Photon Video line of products. This was a set of modules you could use for various video applications, either at home or professionally. This particular tool was for animators to use in arranging and editing frames. It supported all of the different graphics modes on the Amiga and automatically adjusted to the amount of available memory in the user’s machine.

Kildall pointed out that graphics took up an awful lot of storage. So how much memory was required for animation? Douglas said it usually worked fine on an Amiga with 8MB of memory, which was what the demo machine in the studio had. For something like a pencil test, you could fit up to 1,000 frames depending on the graphics mode. And for longer, more complex color sequences, it was maybe 100 frames.

Meanwhile, Turnipseed called up the finished color animation of a man riding the horse. Kildall asked how the coloring process worked. Did you have to color each individual frame? Turnipseed said she did. She could fill a shape and incorporate the line around the outside of the shape, so that the line was actually a deeper shade of the fill color. This was something that was impossible in hand coloring due to the man-hour requirements of traditional cel animation.

Kildall asked if this output was commercially usable for something like a television broadcast. Turnipseed said that when used in conjunction with a third-party product, it was possible. Indeed, she was anxious to test that herself in the near future.

While Turnipseed loaded another demo, Cheifet asked Douglas about the hardware configuration necessary to run Cel Animator. Douglas said it would run on a standard Amiga with at least 1MB of memory. Cheifet asked if it would run on an Amiga 500. Douglas said it would. There were no special hardware video requirements.

Turnipseed then showed a completed animation sequence with characters and a background. The sequence featured an anthropomorphic rabbit jumping out of a top hat in front of a blue curtain. Turnipseed explained that she used the computer to color each frame, pick them up onto the full-color background, saved each of the 80 discrete frames to disk, and colored each one of them.

Kildall asked what this kind of technology meant to the animation industry. Turnipseed said for an individual classic animator such as herself, it meant she could produce her own full-color animation sequence at home. So she could be competitive with a bigger studio.

Producing Multi-Track Audio at Home

Talin of Microillusions joined Cheifet and Kildall for the next segment. Talin, who went under the name David Joiner at the time, was the programmer of Music-X, an audio software package for the Amiga. (Adams Douglas also remained for this segment.)

Kildall asked Talin what the Amiga meant for him as a musician. Talin said it essentially allowed him to set up a multi-track recording studio in his home. Modern synthesizers now all had MIDI capability. This meant synthesizers from different manufacturers could all communicate with one another, and the computer could receive and process that information in various ways.

Talin then provided a demonstration using a Roland D-50 synthesizer keyboard and Music-X running on the Amiga. He made a short digital recording in real time. He then stored it on the computer and played it back. He pointed out that Music-X had on-screen controls just like a take player. On the surface level, it was very simple. But at the same time, you could dig down deep into its innards.

Kildall asked how many separate audio segments could be managed at one time on Music-X. Talin said you could record up to 250 segments in the computer but only play back 20 at a time. Kildall asked how you managed multiple different segments in the software. Talin said the program contained a number of different editors. He pulled up a bar editor, which showed the music as a series of bars. Other options included a “librarian” screen that could send sounds directly to the synthesizer. There were also filters that allowed you to process your playing in real time and change the performance, as well as a key map to redefine the behavior of the keyboard using the functional equivalent of macros. Talin emphasized that he was interested in experimenting with the combination of human and computer musical composition.

Cheifet asked what Music-X did that was new in terms of music software. Talin said the software was affordable and ran on a color machine that was affordable. The Amiga also had a very “creative spirit” that attracted musicians.

Cheifet pointed out that Music-X was actually still in development. He asked Douglas when it would hit the market. Douglas said it would be out in about two months for a retail price of $290. Cheifet followed up, asking if Music-X was targeted primarily at professional musicians or was it for people who were not performers. Talin said the program could adapt to various levels of talent. He noted that he considered himself an amateur musician. But he also wanted something that a professional could use.

Cheifet noted that many musicians currently used the Amiga’s rival, the Atari 520ST. How did the Amiga compare for this type of work? Talin said the Amiga was a little bit more polished in terms of design. And he hoped that Music-X would be able to support a lot more features because of the multi-tasking capabilities of the Amiga.

The Power of Amiga’s Vision

Shifting gears from music to science, Wendy Woods presented her second and final report from the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute in San Francisco, California. She explained that the Institute use dozens of computer-based visual experiments to study human visual perception–specifically, how motion helps people to see. The institute’s director, Dr. Ken Nakayama, created these experiments using Electronic Arts’ DeluxePaint software running on multiple Amigas.

Nakayama told Woods that when the Amiga first came onto the market two years ago, it was really the only machine available that could do the things he wanted to do. It had a great graphics capability and special hardware to move images around without the CPU knowing. That was something you couldn’t do on previous machines.

Woods said that Nakayama believed that Amigas, and microcomputers in general, opened up a whole new field of vision research. The motion that you could achieve on a computer screen simply could not be duplicated by standard eye tests. And the graphics experiments now underway at Smith-Kettlewell could end end up in clinical settings to test actual patients with vision problems.

Could an Amiga Replace a Professional Video Production Setup?

Tim Jenison and Paul Montgomery, the president and vice president, respectively, of Kansas-based NewTek, Inc., joined Cheifet and Kildall for the final studio segment. NewTek was developing an Amiga add-on product called Video Toaster. Kildall opened by asking Jenison why they chose the Amiga. Jenison said that of all of the computers currently on the market, the Amiga was the most well-suited for video use. It could produce NTSC video out of the box without the need for any add-on cards. The Amiga could also display 4,096 colors at once, which was enough to achieve photographic-quality images on the screen. And with certain co-processor chips and internal circuits, the Amiga was a real powerhouse.

Kildall asked about Video Toaster itself. Jenison said it was a peripheral that turned the Amiga into a professional video box. First, there was a display card that allowed the Amiga to display millions of colors on the screen at once at a higher resolution than a standard machine. Second, there was a “frame grabber,” or video digitizer, that could take images directly from a VCR or a camera up to 60 times per second in full color. This feature also made it possible to capture individual frames and store them on disk for later recall. You could also import saved images into a paint program.

Kildall asked for a demonstration of Video Toaster. There were two monitors on the desk hooked up to the Amiga running Video Toaster. Jenison said the software currently displayied a live video feed from a camera that was also sitting on the desk. Video Toaster captured 60 frames per second by default, but you could slow it down, which Jenison did for the demo. He then showed off the software, which could apply a number of effects to the video feed, such as causing the image to “tumble” or zoom. Kildall noted these kinds of video effects were typically quite expensive when done with professional equipment. Jenison concurred, noting such effects cost between $20,000 and $300,000 on traditional video equipment. He added that all of the effects in Video Toaster were software-based, so the more software they wrote, the more effects that would be available to the user.

Kildall asked who the customer was for Video Toaster. Montgomery said it was any of the seven million camcorder owners in the United States. It was also for people who produced video for the educational, sales, and training markets–basically, anyone who had an interest in video or a need to do video. Video Toaster would give those users the “slick” television look that people were becoming accustomed to. Kildall said that if he had a small business and wanted to do video for his public relations department, he could build his own solution using Video Toaster. Montgomery said that was right.

Cheifet asked if Video Toaster could replace the professional-quality broadcast tools currently in use. Jenison said he thought it could. Even if a television station currently had a high-quality unit, they were typically considered a “precious resource” that could cost you as much as $300 per hour to rent. Video Toaster enabled them to own a solution much more cheaply.

Cheifet asked about the next step. What features would be added to Video Toaster in the future? Jenison said there were a number of planned add-on products. The goal was to get the entire production process into a single box. So they were working on the remaining bits and pieces to achieve a “desktop video” solution. Cheifet said that made it sound like an analogue to desktop publishing. But what did that mean in practice? Montgomery said “desktop video” was the marriage of personal computers and video. Kildall asked Montgomery if he really thought consumers would be doing full video editing at home in the future. Montgomery said they would if it was easy enough.

Cheifet closed the episode by asking about the projected cost of Video Toaster. Jenison said that for a whole system, you wound need a VCR, a camera or camcorder, an Amiga, and the Toaster card. Altogether, that setup would run about $2,000. The Video Toaster board alone would cost $799. Cheifet then asked if NewTek was working on any other creative applications for the Amiga. Montgomery said they were developing an NTSC paint program to take the output from Video Toaster and manipulate it, as well as add-on products to do animation and video titles.

NewTek, Video Toaster Outlived Amiga by Decades

Video Toaster was not actually out on the market when this Computer Chronicles episode first aired in early 1988. Indeed, the finished product did not release until nearly three years later in December 1990. By then, the cost of the setup had more than doubled from Paul Montgomery’s on-air projection. According to a 2016 retrospective on Video Toaster by Jeremy Reimer of Ars Technica, the entry-level price was $2,399 for the expansion card plus eight floppy disks, with the complete Amiga package running about $5,000. Although to be fair, the shipped Video Toaster included a lot of the additional features that Montgomery could only speculate about back in 1988, including a title generator and an updated paint program to make graphic overlays.

Of course, there was a NewTek product already available in 1988, and that was DigiView, which Wendy Woods discussed in her first remote segment. Tim Jenison, a native of Topeka, Kansas, was a longtime computer hobbyist. Reimer noted that Jenison built his own digital computer for a seventh-grade science project. After dropping out of college, Jenison started a small business selling software for Tandy computers. Once Jenison purchased an Amiga 1000 in 1985, however, he quickly shifted his focus to the new Commodore machine. He sold the Tandy software business and started NewTek, Inc., to develop DigiView.

Paul Montgomery joined NewTek a short time later. Montgomery, a native of California, had been working at Electronic Arts during their ultimately failed pivot to the Amiga as its primary platform. According to Reimer, it was Montgomery who sold Jenison on the idea of developing what became Video Toaster:

Montgomery asked Jenison if the Amiga would be able to serve as the centerpiece for a video effects generator. Jenison liked the idea, but Montgomery kept pushing: “What about squeezing the image and flipping it?” he asked.

“No, that would take a $100,000 piece of equipment.” Jenison replied.

“OK, yeah, I knew that,” Montgomery said. “But it would be pretty cool if you could do it.”

In the story of the Amiga, there were many points in which an engineer was challenged to do something impossible. In this instance, Jenison went off and thought more about the problem. Eventually, he figured out a way to do the squeezing and flipping effect—and that was the beginning of the Toaster prototype.

When it finally launched, Video Toaster was an unqualified success. It quickly gained a foothold with a number of professional television productions, including the Steven Spielberg-produced NBC series SeaQuest DSV and J. Michael Straczynski’s syndicated science fiction show Babylon 5. In 1993, the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences awarded NewTek and Jenison an Engineering, Science & Technology Emmy for their work on Video Toaster.

Of course, by 1993 the Amiga platform itself was on life support. While Video Toaster was in some respects a “killer app” for the Amiga, it did not lift Commodore in the same way that Aldus’ PageMaker had done for the original Apple Macintosh. And by July 1993, news reports suggested that NewTek might actually have to buy or bail out Commodore to keep the Amiga alive.

That didn’t happen, and Commodore decided to liquidate itself in 1994 and shut down. Video Toaster survived, however, as NewTek ported it to Windows-based systems. NewTek continued to update and service Video Toaster until 2009. The company itself relocated from Kansas to San Antonio, Texas, in 1997. In 2005, NewTek introduced its TriCaster line of video production tools, which effectively replaced Video Toaster. In November 2019, Norway-based Vizrt acquired NewTek, Inc. Shortly before this blog posted in September 2023, Vizrt officially retired the NewTek brand and merged both companies’ product lines, including TriCasert, under the Vizrt name.

Microillusions Another Flash in the Pan

The other company featured prominently in this episode, Microillusions, did not enjoy as long a life as NewTek. Jimmy Maher of The Digital Antiquarian published an extensive history of Microillusions in 2015. Talin learned to program mainframe computers while serving in the United States Air Force in the late 1970s. Like NewTek’s Tim Jenison, Talin initially got into microcomputers making software for the Tandy Color Computer. Talin’s first Tandy game, Guardian, was a 1982 clone of Williams Electronics’ popular arcade cabinet Defender.

According to Maher, Talin first learned of the Amiga 1000 from Jim Steinert, the owner of a Los Angeles computer store:

The seeds of MicroIllusions were planted during one day’s idle conversation when Steinert complained to [Talin] that, while the Amiga supposedly had speech synthesis built into its operating system, he had never actually heard his machines talk; in the first releases of AmigaOS, the ability was hidden within the operating system’s libraries, accessible only to programmers who knew how to make the right system calls. Seeing an interesting challenge, not to mention a chance to get more time in front of one of Steinert’s precious Amigas, [Talin] said that he could easily write a program to make the Amiga talk for anyone. He proved as good as his word within a few hours. Impressed, Steinert asked if he could sell the new program in his store for a straight 50/50 split.

Steinert subsequently formed Microillusions and hired Talin to develop software as an independent contractor. The new company’s first product was Discovery, a series of educational games for the Amiga. Talin was the sole designer and programmer on the project. He followed that up with The Faery Tale Adventures: Book I, an ambitious action-adventure role-playing game, which Maher described as graphically and musically “stunning” for its time yet also “kind of a mess as a piece of game design.”

Talin developed a basic editor called Musica to write the music for both Discovery and The Faery Tale Adventures. He then decided to make a new program targeting professional musicians. Steinert gave him the green light, and the result was Music-X. Talin provided a detailed walkthrough of his development process in a 2018 Medium article. He also described his experience demonstrating the Music-X prototype on Chronicles:

I had been in a panic because I had forgotten to bring the power cord for the Roland D-50. However, I was able to unscrew the back panel of the D-50, and using alligator clips from the electronic workbench at the TV studio, rigged a power cable for it just minutes before the session. You may notice that the arrangement of objects on the desk where I am sitting carefully conceals the jerry-rigged cables.

Like Video Toaster, Music-X was not ready for market when this Chronicles episode aired. Music-X finally released at the end of 1989. Talin later recalled he only made about one-quarter the money on Music-X that he did from Faery Tale Adventures, largely because he agreed not to take an advance against future royalties on Music-X.

Unfortunately, while Music-X reviewed well, it came out at a time when Microillusions was, in Maher’s words, “already in dire straits, their phones perpetually coming on- and off-line and rumors swirling about their alleged demise.” That demise occurred at some point in 1992 or 1993 based on California state records. Talin continued to work as an independent contractor before starting his own company, The Dreamers Guild, Inc., in 1991. Among the new company’s first projects was a sequel to Electronic Arts’ Deluxe Music Construction Set, the Amiga rewrite of Will Harvey’s Music Construction Set.

In 1994, Talin and The Dreamers Guild created an adventure game, Inherit the Earth: Quest for the Orb , for New World Computing. Talin said the game “was not a commercial success,” selling fewer than 20,000 copies at launch, although a German-language port did modestly better. Talin then decided to create a sequel to Faery Tale Adventures, which Encore Software, Inc., published under the name Halls of the Dead: Faery Tale Adventure II in 1997. This game was also not successful, and essentially drove both Encore and The Dreamers Guild out of business.

Talin went on to work for a number of failed software startups before joining Electronic Arts’ Maxis subsidiary in 2002, where he worked on the team that produced SimCity 4 and The Sims 2. He left the games industry altogether in 2007 and moved over to Google for the next eight years as a software engineer. In 2016, Talin joined yet another startup, Nimble Collective, Inc., which Amazon Web Services acquired in 2019. Talin remained with Amazon until he retired in 2021.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was first broadcast in late January or early February 1988. The recording at the Archive is a rerun that aired during the week of July 14, 1988.

- Paul Schindler’s software review was for a sample disk of Microsoft Excel templates sold by Heizer Software for $4.

- Bob Dinnerman designed and programmed F/A-18 Interceptor for Electronic Arts. In a 2004 interview with Tom Steinberg, Dinnerman recalled that he’d been working as an arcade developer for Bally/Midway when he attended the 1984 SIGGRAPH conference and saw a demonstration of high-end flight simulation software. A developer approached him at the show and asked if he’d be interested in creating a combat flight simulator for the Amiga. He left Bally/Midway and proceeded to create a demo for Interceptor, which EA agreed to publish.

- Heidi Turnipseed worked as an animator for both Walt Disney and Don Bluth Productions. Aside from assisting Microillusions in developing its animation software, she was also credited on the 1988 MS-DOS game based on the movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

- Dr. Ken Nakayama earned his bachelor’s degree in psychology from Pennsylvania’s Haverford College in 1962 and later his his master’s and PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles. After a two-year stint teaching at a medical school in St. Johns, Newfoundland, Nakayama joined Smith-Kettlewell in 1971. He remained there until 1990, when he joined the psychology department at Harvard University. At Harvard, Nakayama started the Vision Sciences Laboratory, which he oversaw until his retirement in 2016.

- Tim Jenison remained with NewTek as its chairman until the Vizrt acquisition in 2019. In 2013, director Teller (of Penn & Teller fame) released a documentary, Tim’s Vermeer, which chronicled Jenison’s attempts to duplicate the techniques used by 17th century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer.

- Paul Montgomery died in June 1999 at the age of 39 after suffering a heart attack while on vacation. Montgomery left NewTek in 1994 after a falling out with Tim Jenison and co-founded a new company, Play, Inc., which developed Snappy Video Snapshot, a PC image capture device. That company folded not long after Montgomery’s death.

- Larry Keenan died in August 2021. Born in 1943, Keenan became internationally known for his photographs of the Beat Generation in the 1960s, which are now part of the Smithsonian Institution’s permanent collection. He went on to become a successful advertising and corporate photographer who was among the early adopters of digital technology. Among his clients were Electronic Arts, for whom he designed the box cover art for the 1988 Amiga release of Deluxe PhotoLab. In 2011, Kurt Hemmer and Tom Knoff produced a 40-minute documentary on Keenan’s life and work photographing the Beat Generation.