Computer Chronicles Revisited 101 — The DataCopy 830, ImageStudio, TrueForm, and PicturePower

Computer Chronicles began 1988 with a focus on desktop scanners and digital imaging software, a field still in its earliest stages at the personal computer level. Stewart Cheifet opened this episode by showing Gary Kildall a portable scanner that used Xerox copier technology. He pulled the scanner over a printed page, and it produced a CVS receipt-like printout right away.

Cheifet noted that everyone seemed to be into scanning these days. Why the sudden fascination with this technology? Kildall said desktop publishing was a prime reason. People wanted to incorporate more graphics into their text documents. A second reason was the growing popularity of fax machines. But the big movement was towards the digital representation of information in electronic form. That made it a lot easier to assemble information, put it together, alter it, and publish it. It was simply a more flexible way to deal with information.

The PC–Now with the Power of Facsimile!

Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment, narrating some B-roll footage taken at Inter-Ocean Leasing in San Francisco, California. Woods said Inter-Ocean leased containers for shipping cargo around the world. The firm had agents in 26 countries and it needed to communicate with those people every day.

The company used to rely on a Telex, Woods said. But it recently changed to a PC-based facsimile (fax). David Shakespeare, an Inter-Leasing vice president, told Woods there were two main advantages. One was that a fax system could transmit images, which was useful for sending things like contracts or drawings. The second was the cost effectiveness. You could take advantage of economy long-distance phone rates and send the fax whenever it was cheapest.

Woods said that the hardware for a computer-based facsimile included a plug-in fax card, a scanner, a laser printer, and software. A complete system could send and receive text or images at preset times, and it could store documents to disk to be retrieved later. And while the electronically transmitted image lacked definition on screen, the laser printout was more than respectable. Shakespeare added that the PC could still be used as a PC since the fax software worked in the background.

256 Shades of Gray

Rolando Esteverena and Jerry Borrell joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Esteverena was the president of Datacopy Corporation. Borrell was the editor of MacWorld. (There was also another Datacopy employee present to assist Esteverena with his demonstration.)

Kildall opened by asking Borrell about the importance of scanning to desktop publishing on both the PC and the Macintosh. Borrell said a lot of scanner vendors, such as Datacopy, had started migrating from the PC to the Mac because of the rapid development of desktop publishing. In particular, the more recent 8-bit scanners were becoming more important in desktop publishing because of the need for halftone printing.

Killdall then asked Esteverena about his company’s desktop scanner, the Datacopy 830. Esteverena explained that his company produced a range of products ranging from low-cost to higher-end, high-performance scanners. He agreed that the growth of desktop publishing on the Mac had been driving the demand for better scanners. The Datacopy 830 itself could be thought of like a copier, only instead of making a copy to paper, it made a copy into computer memory.

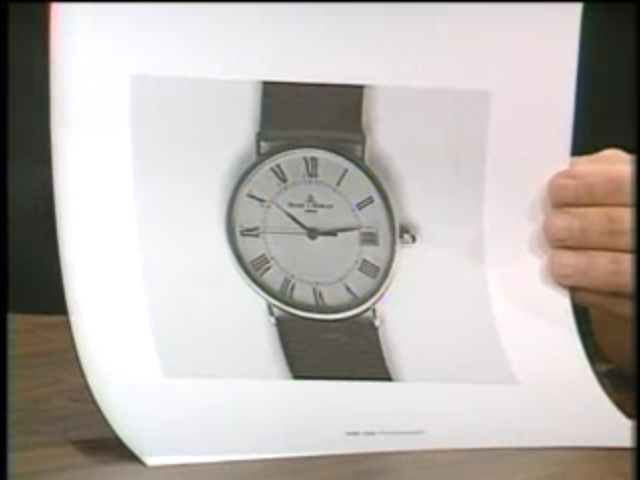

Esteverena then demonstrated the Datacopy 830 by scanning an image into a Macintosh II. He noted the scanner created the image, and then the included software–MacImage, also developed by Datacopy–analyzed the content of that image. This analysis focused on picture quality, particularly the level of detail. To illustrate, he showed a printout of a scanned image of a watch (see below). And thank to the Macintosh’s ability to produce gray-scale, it was now possible to produce images for desktop publishing that nominally reflected photographs (albeit black-and-white photographs).

As Esteverena talked, his colleague finished scanning in an image of a woman’s face into the Macintosh (see below). Esteverena explained how the software controlled the contrast, brightness, and other factors in the digitized image. He also demonstrated a function called “gamma correction,” which changed the tones in the image.

Kildall asked about the memory requirements to store the image, noting the Datcopy 830 had a resolution of 300 dots per inch (dpi). Esteverena said an 8.5-by-11 image at 1-bit color depth (i.e., black and white only) took up about 1 MB of disk space. If you used gray-scale, however, that required additional space.

Kildall then asked if the MacImage software could resize images, which would be necessary for many desktop publishing applications. Esteverena said yes, the software could change the shape, content, and size of the image.

Cheifet asked Borrell if desktop publishing was the only application for this type of scanner. Borrell said no, some of the original scanners were developed for optical character recognition, but that research never came to fruition. So graphics scanning for desktop publishing was now the most popular application, but not the only one. (Esteverena later interjected that Dadtacopy did offer optional software to enable optical character recognition with its scanner.)

To wrap up the segment, Cheifet asked Borrell what factors a consumer should look for when buying a scanner. Borrell said there were several things. First, what was the dots per inch? Second, what were the number of bits it could capture? An 8-bit scanner was necessary to capture a full 256 gray-scale. Third, what were the supported file formats? If the software saved to a format like TIFF, you could use the scanned image with third-party applications like ImageStudio. Finally, how well did the manufacturer support the product after you took it home?

The Latest Advances in Digital Wrinkle-Removal Technology

Mark Zimmer and Mitch Stein joined Cheifet and Kildall for the next segment. Zimmer was president of Fractal Software, which developed the aforementioned ImageStudio. Stein was president of Spectrum Digital Systems, which developed another scanning software package, TrueForm.

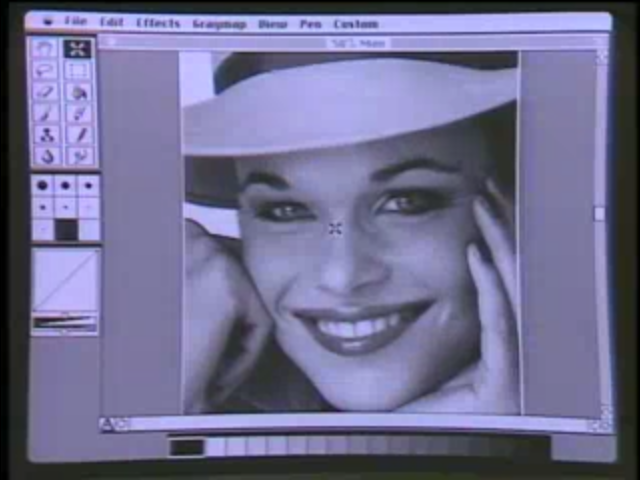

Kildall asked Zimmer how his software was used in desktop publishing. Zimmer said the average person might use a scanned picture in a desktop publishing package like Ready, Set, Go! or PageMaker. To demonstrate, he pulled up ImageStudio on a Macintosh, which displayed a sample image of a woman’s face (see below). He showed how you could zoom in on the image to look at the finer details. For instance, this woman had a wrinkle in her eye. Zimmer said he would use the software to try and get rid of it. (Funny how they never use images of men in these demos.) He selected a sample texture from another part of the face and copied it over the wrinkle. Zimmer also showed how you could change the contrast and brightness in real time–i.e., the software automatically made the changes as you manipulated the controls–which was similar to the gamma correction function seen in the previous Datacopy MacImage demonstration.

Cheifet asked how fine could the changes be? He pointed to another wrinkle in the image of the woman’s face. (Really, Stewart?) Zimmer then removed the second wrinkle using the same technique as before.

Kildall asked how the resolution of a scanned image compared to that of a 35mm photograph. Zimmer said ImageStudio could support any resolution. It depended on the scanner used. With a 300dpi scanner, you could input 8 bits per pixel, which would give you an 8 MB image on disk. But one of the benefits of ImageStudio was its ability to compress an image, so you would only need about one-third or one-fourth of that space.

Cheifet asked Zimmer to explain the importance of gray-scale and halftones in desktop publishing for people who were not artists. Zimmer said that when you output a picture to a PostScript device, it used halftones to show the picture because the device was only black-and-white. ImageStudio had full halftone output capability, as well as allowing for several different “screens” to create visual effects.

Turning to Stein, Cheifet asked about his program, TrueForm, which was used to scan forms. Stein noted that scanning in a form took up a large amount of data. He showed a sample one-page form, which scanned at 300dpi would take up 1 MB of memory. And then if you had to run the necessary operating system and software on top of that, you would need a Macintosh with at least 2 MB of memory. TrueForm controlled the scanning process and compressed the image “on the fly,” so that the image only took up about 80 to 85 percent of the space.

Stein added that TrueForm addressed the Macintosh’s display resolution limits, which was just 72dpi. So the software created a second version of the scanned image that could be displayed on the screen, while preserving the higher-resolution version for printing. Cheifet noted this answered his earlier question about what you could do with a scanner besides desktop publishing. Stein then showed a printout of the scanned form he created with TrueForm, which closely matched the original form.

Pixar’s Pivot to Medical Imaging

Wendy Woods returned for her second remote segment, which opened with scanned images of a human skull. Woods said that this was a dream for many doctors: the ability to look inside the human body without surgery. And this technology–called volume imaging–was created by a company called Pixar. (Yes, that Pixar.)

Data from CAT scans and other sources were fed into Pixar’s computer, Woods said, and used to generate a variety of views of the body. Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, was among the few hospitals to regularly use the Pixar in diagnosis. Doctors said the images alone had changed their decisions regarding operations or implants in about one-quarter of their cases. But many wondered why it took so long for this technology to produce these kinds of images.

Pixar co-founder Alvy Ray Smith told Woods that memory was the main reason. Specifically, computer memory wasn’t large enough–i.e., it wasn’t cheap enough in large quantities–and the processing power required to address that memory wasn’t cheap enough. But now those things had changed. And Pixar was the first company to exploit cheaper processing power and memory.

Woods said that while the Pixar computer (see below) was not exactly inexpensive at $50,000, just two years ago that same machine was nearly triple the price. Now, the medical community was so enthusiastic about the technology, Pixar staff predicted that most radiologists would be using these computers within the next five years. By then, the technology was also expected to fit inside of a desktop machine and be radically less expensive.

Moving Beyond Paper and Film?

Jennifer Moller and Michael Marcus of PictureWare joined Cheifet and Kildall for the final studio segment. George Morrow was also present.

Kildall asked Marcus, PictureWare’s president, how his company product, PicturePower, differed from those previously demonstrated. Marcus said his software enabled you to get real-world color picture–via video camera–into a computer database. You could then treat that picture as thought at it were just another field in that database, so you could combine it with text and later retrieve those images based on whatever attributes you defined.

Kildall asked about the hardware requirements for PicturePower. Moller, PictureWare’s marketing director, showed the setup (see below). There was a video camera hooked up to a board inside of an IBM PC-compatible computer. This board captured the analog image and converted it into a digital file for storage. You could then display the image on a monitor.

Marcus then demonstrated some applications of the database software, including pictures of houses for a real estate broker, a jewelry store inventory, digitized images of signatures for identity verification by a bank, and security photos for an employee ID system, among other examples. Cheifet asked if PicturePower worked with other databases. Marcus said the software had its own internal database manager and data communications module. But it was also capable of operating with other database managers.

Moller continued the PicturePower demo, which showed the actual database manager. She said you could customize the database to display multiple pictures per entry. You could also annotate individual images. She then explained the database manager’s query function, which allowed users to search for a specific entry. She also demonstrated how to add a new picture to the database.

To end the episode, Cheifet asked Morrow for his thoughts. Morrow said that most of the information in society was either on film or 8.5-by-11 sheets of paper. This type of scanning hardware and software allowed you to treat all of this information the same as you did a name and address. That would have enormous benefits. For example, many grocery store chains used barcode scanners to gather information about how well certain products sold. When you had more information to manipulate, there was much more there than met the eye. And now it would be possible to digitize information that was not readily available at the moment.

Pixar Co-Founder Forced Out by Raging Asshole

Pixar, Inc., is one of those companies that’s been mentioned in passing a few times on Computer Chronicles but not directly featured until this episode. Back in January 1986, Stewart Cheifet reported during “Random Access” that the recently released film Young Sherlock Holmes featured a computer-generated special effect of a knight jumping out of a stained-glass window. Cheifet noted that it took six engineers working with the Pixar computer about nine months to create the 38-second shot.

What became Pixar started out as a computer graphics research group at the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) led by Edwin Catmull and including Alvy Ray Smith, who earned his doctorate in computer science from Stanford. The group’s goal from the start was to create a fully computer-animated film. But when NYIT ran into financial problems, Star Wars director George Lucas hired Catmull, Smith, and several of their colleagues to join his company, Lucasfilm, Ltd., to continue their work as the company’s new computer division.

Lucas’ subsequent divorce led him to spin-off the computer division into a separate company, with deposed Apple co-founder Steve Jobs purchasing a majority interest for $5 million. This was 1986, nearly a decade before Pixar would finally realize Catmull and Smith’s goal of releasing an animated feature film. In the meantime, Jobs was eager–and probably desperate–to realize an immediate return on his investment. So Pixar pivoted towards developing computer graphics hardware targeting the medical industry. As Smith told Bart Eisenberg of the San Francisco Examiner in December 1987, “We came here to do Lucasfilm’s bidding and start a graphics lab. But five years ago, I’d have never guessed that we’d be in the medical business.”

The move received approval from market analysts, one of whom told Eisenberg:

Pixar has made an important transition from research center to profit center. They have begun to operate as a business. Pixar has a ‘gee-whiz’ product–but they are running with the realization that you need more than that. A lot of companies never get to that point.

Of course, selling machines that cost between $50,000 and $100,000 wasn’t exactly a high-volume business in 1987. Indeed, Smith told Eisenberg that Pixar had only sold about 110 machines total. In February 1988, Pixar released a less-expensive model–the $30,000 Pixar II (or P-II). But Jobs and the Pixar management quickly realized that hardware was not the path to profitability. In 1990, Pixar sold off its hardware division to Vicom Systems for $2 million. Pixar then redoubled its focus on animation software, which in turn led to the production of its first feature film, Toy Story.

Sadly, Smith left Pixar just after Toy Story got the go-ahead to start production in 1991. (The film was not completed until 1995.) A 2021 Wired profile of Smith by Steven Levy pointed to Jobs as the main reason for Smith’s departure:

Smith and Jobs routinely butted heads. Jobs often began meetings with an intentionally outrageous statement, and Smith made a point of pushing back. “It was a pure ego competition—Alvy wanted his vision to be dominant, and there was no way that was going to happen,” says Pam Kerwin, who was Pixar’s general manager.

Meanwhile, Pixar kept making short films that won acclaim. One, about lifelike desk lamps, even got nominated for an Oscar. Jobs saw them as marketing vehicles; Smith and Catmull saw them as test runs for The Movie.

At first Jobs tolerated Smith’s aggressions. Eventually, though, he began to lose patience. And then came the whiteboard incident. At a Pixar board meeting in 1990, Jobs was complaining that Pixar was behind on a project. Smith said that NeXT was behind on its products. As Smith recalls it, Jobs began mocking Smith’s Southwestern accent. “I had never been treated that way. I just went crazy,” Smith says. “I was screaming into his face, and he’s screaming back at me. And right in the middle of that crazy, absolutely insane moment, I knew what to do. I brushed past him and wrote on the whiteboard.”

Those few feet to the whiteboard took Smith past the point of no return. No one wrote on Steve Jobs’ hallowed whiteboard. As Smith took the marker and scrawled—he doesn’t even remember what he wrote—he was committing Steve-icide. “I wanted out of there,” he says. “I didn’t want that guy’s poison in my life any longer.”

After Pixar, Smith co-founded Altamira Software Corporation, which developed image editing software for the IBM PC platform. Microsoft purchased Altamira in 1994, essentially to gain Smith’s expertise. Smith stayed on with Microsoft until 1999, when he largely retired from the industry. In 2021, Smith released A Biography of the Pixel, which includes a semi-autobiographical look at his own role in helping to build the computer animation industry.

Datacopy Made More Money Selling Business Than Scanners

Ridiculously expensive hardware was really the theme of this episode. The Datacopy 830 desktop scanner was another case in point. While the scanner tested and reviewed well, it retailed for $2,800. And that didn’t include the MacImage software or the SCSI interface to actually connect the device to a Macintosh. With those “extras,” the total price of the scanning package demonstrated on Chronicles came to around $3,500.

Jim Heid, reviewing the Datacopy 830 for the January 1988 issue of MacWorld, said MacImage was “what really sets the 830 apart” from the other 300dpi scanners then on the market:

The programs accompanying most scanners have bare-bones gray-scale features. Rarely can you edit gray-scale images or change their brightness and contrast (a process often called gamma correction). For gray-scale work, you need to spend a few hundred dollars for an image-processing program such as Letraset’s ImageStudio or Silicon Beach’s Digital Darkroom.

Heid added, however, that MacImage was prone to crashing in his tests. And overall, he felt the $3,500 price tag for the 830 package was too high. So his advice was to “shop around” unless there was a good deal available for the Datacopy machine.

Much like Pixar, Datacopy struggled to make money on its innovative but expensive hardware. In 1987, the company reported a $1.3 million loss on $13 million in sales. Fortunately, its scanner technology was desirable enough to attract a buyer for the company. In May 1988- just a few months after this episode aired–Xerox purchased Datacopy for approximately $31 million in cash.

Rolando Esteverena stayed on for time after Datacopy became a Xerox subsidiary. But he eventually departed the company and took over as CEO of Arizona-based ADFlex Solutions, a manufacturer of computer parts. ADFlex was a spin-off of another company, Connecticut-based Rogers Corporation, which sold what had been an unprofitable division to a group of managers and investors. Esteverena led the newly independent ADFlex to profitability for several years, but after the company posted a $2.6 million quarterly loss in early 1999, he resigned as chairman and CEO. Esteverena subsequently co-founded and served as CEO of a tech startup, Boats.com, a search engine for people looking to buy boats. That company was later sold and remains in business today.

Zimmer’s Painter Journey

Mark Zimmer and Tom Hedges created ImageStudio under a partnership they called Fractal Software. Zimmer, who had been a programmer since the mid-1970s, recalled on his blog in 2011 that their first commercial product was SoundCap, an audio digitizing program. Zimmer then started working on a project he called “GrayPaint,” which he intended to be a a “more realistic drawing” program. It was Hedges who proposed tying this program to scanners.

Zimmer and Hedges showed their combined prototype for what was one of the first image editing programs to Marla Milne, a manager at Letraset USA, the company that distributed the desktop publishing package Ready, Set, Go! Letraset agreed to publish Fractal’s digital imaging software, which was named ImageStudio. Letraset subsequently commissioned Fractal Software to develop a color version, which was called ColorStudio.

In 1990, Letraset closed its software division, which meant ImageStudio and ColorStudio would no longer earn any royalties for Fractal Software. By this point, Zimmer was working on a new computer drawing program, which he called Painter. A few months later, Zimmer and Hedges turned their partnership into a company, Fractal Design Corporation, with Zimmer as president and CEO and Hedges as chairman. Fractal Design formally launched Painter at the August 1991 Macworld Expo in Boston. At the show, Zimmer recruited an experienced artist, John Derry, to join Fractal Design as a vice presiden. Derry would go on to co-develop future releases of Painter with Zimmer and Hedges.

Painter proved an enormous success from the outset. So of course, Fractal Design decided to go public. The company’s November 1995 initial offering raised approximately $20.5 million. The company shortly thereafter announced plans to move into a new 40,000 square-foot headquarters located in a historic property in Santa Cruz, California. A few months later, in February 1996, Fractal made its first acquisition as a public company, buying Ray Dream Inc., a 3D graphics software company, in a stock swap valued at $47 million.

One year later, in February 1997, Fractal Design agreed to merge with another company, MetaTools Inc., in yet another stock swap. This was really a MetaTools acquisition as its shareholders retained a majority of the combined company’s stock and board seats. Leslie Wright, Fractal’s chief financial officer at the time, told the press that one reason for the deal was the uncertain future surrounding Apple, which was still the main platform for Painter. Fractal was struggling somewhat as a result, and MetaTools had a growing business developing drawing software that targeted the amateur market, as opposed to the industry professionals served by Painter.

After the deal closed on May 30, 1997, the combined company was renamed MetaCreations Corporation., with Jim Wilczak, the CEO of MetaTools, remaining in that role. Zimmer became MetaTools chief technical officer, with Hedges taking the role of chief systems architect. Wright, who was let go, was nevertheless bullish on the company’s future, telling Jennifer Pittman of the Santa Cruz Sentinel, “I’ve seen mergers that have gone well, and I’ve seen mergers that have gone terribly. I think this one has a much higher chance of being one of the goods ones.”

Well, Wright probably spoke too soon. The board quickly replaced Wilczak with an outside CEO, Gary Lauer, who decided that MetaCreations should pivot to being a “creative web company.” (Remember, it was the dot-com bubble.) But creative didn’t mean profitable. And in fact, MetaTools/MetaCreations wasn’t profitable either before or after the Fractal Design merger. In December 1999, MetaCreations announced it would report a fourth-quarter loss of around $40 million. At that point the company fired half of its staff–including Lauer–and Zimmer then stepped into the CEO’s role.

But this was just a temporary move. The board instructed Zimmer to sell off the graphics division–i.e., the part of the company that made Painter–so that MetaCreations could double-down on its efforts to focus on “electronic-commerce visualization products,” according to Bloomberg News. (MetaCreations renamed itself twice more before it was acquired in 2008.) Zimmer complied, and MetaCreations sold Painter and its related products to Canada-based Corel Corporation in early 2000. Zimmer then resigned as CEO and he, Hedges, and Derry formed a short-lived consulting company called Fractal.com to advise Corel on what was now Corel Painter.

In 2003, Zimmer joined Apple as a software development engineer, where he remains to the present day.

PictureWare a Brief Diversion in Marcus’ Career

Michael Marcus had a long career in the software industry before coming to PictureWare. Born in 1938, Marcus grew up in New York City and earned a physics degree from Brooklyn Polytechnic University (now the New York University Tandon School of Engineering). Through a friend of his stepfather, Marcus got his first job with Sperry Gyroscope Company in 1959, where he had to teach himself assembly language so he could program a specialized computer used to calculate navigational data on submarines.

In 1962, Marcus joined Computer Usage Company, a software consulting firm, where he worked on projects like air traffic control systems. Eventually, Marcus decided to start his own consulting company, Realtime Programming Corporation. Marcus ended up merging Realtime Programming into a new entity called Realtime Systems, which had been formed by two of his existing consulting clients. Among Marcus’ projects for Realtime was an order matching system for stock brokerages.

After Realtime Systems was sold in 1969, Marcus bought back the rights to his order-matching software and set up a new company, System Implementation Corporation. That company shut down around 1973. Marcus recalled in an 2013 interview with Burton Grad for the Computer History Museum that with a slowdown in the economy–which hit the brokerage business especially hard–he simply ran out of money. So he decided to wind down the business and became an independent consultant for the next 12 years.

PictureWare came about because of David Sherdel, whom Marcus had worked with on one of his consulting projects. According to Marcus, Sherdel had the idea for creating a system to capture and store photographic images in a computer database. Sherdel wanted Marcus to actually run the business, and he agreed.

Through a contact, Marcus met with Safeguard Scientifics Inc., a Philadelphia-based venture capital firm, which agreed to invest $2.2 million in PictureWare, which was also based in Pennsylvania. This funded the release of Picture Power. Marcus recalled to Grad, “[I]t was the very early days for that kind of technology, but we actually did start to sell units here in the United States. And we sold units in the Netherlands.”

And to continue our theme, the complete PicturePower system demonstrated in this episode cost $6,230. This included the camera, the add-on board (which was made by AT&T), and all of the necessary cables. The software was also available separately from AT&T for $945.

For some reason, Safeguard Scientifics didn’t see much long-term potential in this product. With the money running out–and Safeguard unwilling to invest more–Marcus decided to leave and joined another company, AGS Management Systems, as its CEO in 1989. Shortly thereafter, in October 1990, Safeguard sold its majority interest in PictureWare to Oklahoma City-based Norick Software Inc. According to a contemporary report by Jim Denton of the Daily Oklahoman, PictureWare had gross sales of just $800,000 in 1989. And Norick, which developed rating software for the insurance industry, apparently didn’t pay Safeguard any money upfront for PictureWare. Instead, Norick promised to continue paying royalties to Safeguard on future sales of PicturePower. But it doesn’t appear that Norick kept the product line going for long after the acquisition.

As for Marcus, he remained with AGS Management Systems until it was sold by its parent company in 1993. Marcus then joined the IT services company Unisys, which coincidentally was formed when Marcus’ first employer, Sperry Corporation, merged with Burroughs Corporation in 1986. Marcus later relocated to California and joined SPL WorldGroup, which was acquired by Oracle Corporation in 2006. Marcus officially retired after the sale but continued to consult for Oracle for several more years.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and first aired during the week of January 6, 1988. The recording uploaded to the Archive was a rerun that aired during the week of December 16, 1988.

- Paul Schindler’s software review for this episode was Gofer, a $60 program from Microlytics that enabled users to index and search their text files.

- Mitch Stein and John Carnes founded Spectrum Digital Systems in 1984. The company was based in Madison, Wisconsin, and developed its TrueForm software thanks partly to grants from the University of Wisconsin and investment from the City of Madison. Several months after this episode aired, In October 1988, Adobe Systems purchased the privately held Spectrum Digital Services for undisclosed terms. Adobe subsequently released Adobe TrueForm 2.0 in 1989.

- Mitch Stein stayed on with Adobe after the sale of Spectrum Digital Systems. In 1990, he co-founded a short-lived startup, Slate Corporation, which focused on pen-based computing technology. He later had stints at Apple, IBM, Oracle, and Yahoo, among other companies. In 2015, he co-founded DocAmp, a healthcare technology company. Since 2006, he’s also had his own user experience consulting firm, Stein Design.

- Textainer, the parent company behind Inter-Ocean Leasing, is still in business today. Founded by Ken George and Jim Sullivan in 1979, Textainer reported over $2 billion in active shipping container leases as of 2021.