Computer Chronicles Revisited 100 — Strategic Conquest, Beyond Dark Castle, Apache Strike, Chuck Yeager's Advanced Flight Trainer, and Mean 18

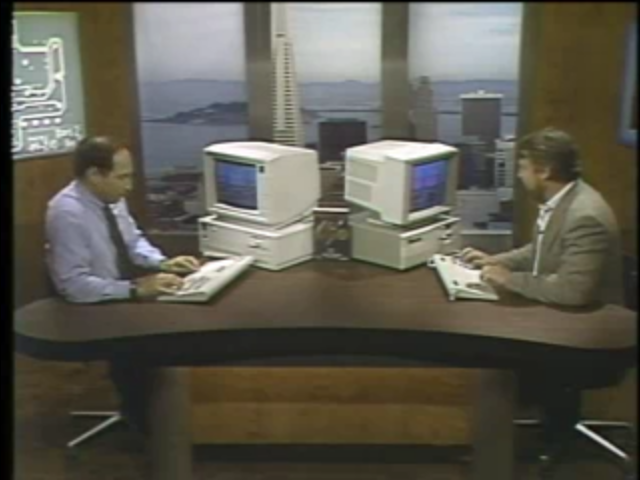

You always have to be cautious when declaring something was a “first” in video game history. But I think that Stewart Cheifet and Gary Kildall held what might have been the first nationally televised LAN party at the start of this December 1987 Computer Chronicles episode, the second in a two-part series on computer games. The dynamic duo demonstrated Falcon, an F-16 combat flight simulator published by Spectrum Holobyte. Cheifet explained the two PCs on the desk were networked so they could “see” each other. There was also a “flight recorder” built-in to the game so that if either player crashed, they could go back and see what they did wrong.

Cheifet noted that while these games were sophisticated, some parents worried that their kids spent too much time playing them. Kildall retorted that many computer games were educational. For example, games were often a child’s first exposure to using a computer, so it taught them skills like using a mouse. It could also help improve hand-eye coordination and problem solving skills. Some games even taught scientific concepts, such as Asteroids and the effects of gravitational pull. But Kildall conceded that based on the experiences of his own children, it was possible for kids to “O.D.” on these games.

Could Computers Teach Kids Diplomacy?

Continuing with this idea of games as educational, Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment, narrating B-roll footage taken at Crocker Middle School in Hillsborough, California. Woods said that educational software had come a long way since the first math and spelling drills found their way into elementary schools. Teachers now had a choice of role-playing adventure games that both entertained and teached.

At Crocker Middle School, teacher Donna Howar used a game called The Other Side to simulate international conflicts. Howar told Woods her class focused on teaching problem-solving strategies. This included learning how to negotiate, how to work in a cooperative group, and how to make decisions together. Another goal was to learn how to organize and extrapolate information.

Woods explained that in The Other Side, two teams of four students tried to build a bridge to the other team’s country. The teams competed for the needed resources and money. Players divided their time between the computer and a conference table, where they planned strategy and reviewed their progress. Howar noted that in her experience, students preferred to be put in a position where they were “acting” something out and there was some sort of reward.

While Howar’s students might not be ready to work at the State Department, Woods quipped, the game seemed to be having an effect. During a recent summit between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev, the students discussed the likely strategies used by the two sides–not bad for a group of kids in their early teens.

Macintosh Gaming Featured Detailed Battle Sims, Interactive Cartoons

Peter Merrill and Eric Zocher joined Cheifet and Kildall back in the studio. Merrill was a software designer with PBI Software in Foster City, California. Zocher was vice president of development with Silicon Beach Software in San Diego, California.

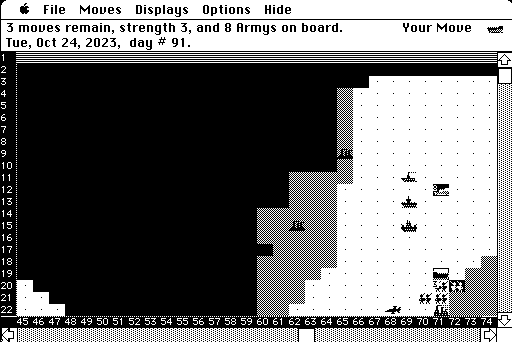

Kildall opened by asking Merrill if kids were as caught-up in his game–Strategic Conquest–as they were other computer games? Merrill said definitely, although he emphasized this was a game that adults liked to play. Strategic Conquest was a strategy wargame for the Macintosh. He had a demo running in-studio on a Macintosh SE. The game screen consisted of a map divided into square sectors. Since the Macintosh had a monochrome display, water was represented in white, land was grey, and unexplored areas of the map were black. Various pixel-sized pieces dotted the map (see below). Merrill explained that you explored the map by moving those pieces.

Cheifet clarified this was not a map of the Earth. Merrill said the game map was produced using a random number generator. He continued the demo, explaining that he owned four islands on the map. The computer-controlled enemy owned two other islands. Merrill’s strategy was to conquer one of those two islands. To do that, he loaded troops onto transport ships and dumped them off on a neighboring island in order to divert the enemy’s attention. Meanwhile, Merrill loaded additional troops and dumped them on the island he wanted to conquer.

Merrill then switched to a different screen that showed the action of the battle. He noted that you could hear the sounds of the computer “jets” as they moved around the map. Although Merrill had the computer move the pieces automatically, he clarified that in normal play you would use the mouse to point-and-click where you wanted each unit to go. The battle map also displayed individual cities on the island. The player and enemy units on land were represented in white and black, respectively. In the demo, the player pieces were trying to capture the enemy’s cities. Merrill said this was the key to the game, as cities produced more pieces. So the more cities you controlled, the more powerful you became. The ultimate goal was to capture all of your opponent’s cities.

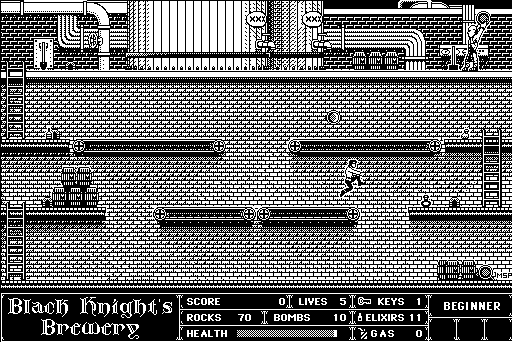

Cheifet then turned to Zocher and asked him to demonstrate the first of two Silicon Beach games, Beyond Dark Castle, which he had described as an “interactive cartoon” (see below). What did that mean? Zocher said it was like a cartoon experience in that there was a lot of detailed animation and a digitized soundtrack. Zocher than provided a demonstration on the Macintosh. (Again, this game is in black-and-white.) He entered the game’s practice mode, which displayed the player character flying in the middle of a swamp. This was one of 14 “rooms” or levels in the game. The player had to defeat a flaming-eye enemy by throwing rocks at it. Zocher added that in another room, he could acquire a spell from a wizard to obtain fireball-throwing capabilities. The goal of this particular room was to get to the end of the level and acquire one of five magic orbs, which was necessary to win the game. After defeating the enemy, Zocher flew his character to a shack that contained the orb. He then picked up a new weapon and used it to fight an enemy guard wielding a mace.

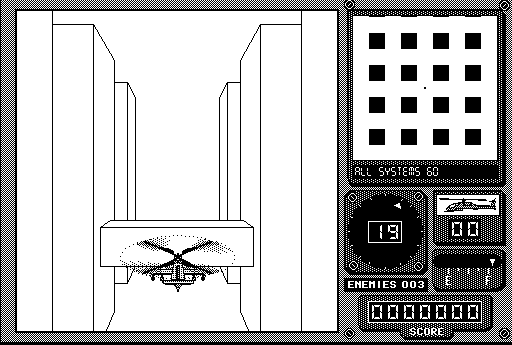

Cheifet asked about another Silicon Beach game, Apache Strike, which involved flying a helicopter–but it wasn’t a helicopter simulation. Zocher said it was an “action fantasy” game. He pulled up a demo on the Macintosh starting on level 20. The game showed a helicopter flying through a 3D wireframe model of a city (see below). Zocher explained you flew the helicopter using the mouse. The goal was to find a “strategic defense computer” while dodging fire from enemy tanks and helicopters. An indicator on the right told the player how many blocks they were from the computer. Cheifet noted there was a “cracked” screen on the right-side panel. Zocher said that was the player’s radar screen, which had been damaged by enemy fire.

Cheifet noted there was a voice providing commentary. Zocher said that was “Linda,” the player’s on-board computer in the helicopter. It was actually the digitized voice of one of Silicon Beach’s programmers.

Cheifet asked about the number of levels in the game. Zocher said you could go up indefinitely. There were 500 levels programmed in. The player could choose to start on levels 1, 20, or 40.

Kildall complimented the smooth animation in the game. How did they accomplish that? Zocher said this was 3D animation with hidden surface removal. He credited the programmer, Bill Appleton, with achieving 20 frames per second using this technique.

Cheifet asked Zocher about the “next step” in terms of computer game technology. Zocher said there was a new technology on the horizon called Compact Disc-Interactive (CD-I) that he thought had a possibility to produce a lot of interesting new games. (Spoiler: It didn’t.) Kildall asked when CD-I might arrive on the consumer market. Zocher said he thought it would be by the end of 1988. (Spoiler: It wasn’t.) Cheifet asked Merrill the same question: What was next for computer games? Merrill said he thought faster computers would mean better artificial intelligence in games.

CompuServe Banking on MUDs

Wendy Woods presented her second segment, which discussed Island of Kesmai, a Dungeons & Dragons-style game for the PC. Woods narrated B-roll of Michael Orkin, a statistician and former Computer Chronicles guest, playing Kesmai for the first time with two other players who were 2,000 miles away in real time via CompuServe. (It should be noted CompuServe was a presenting sponsor of Computer Chronicles for this season.)

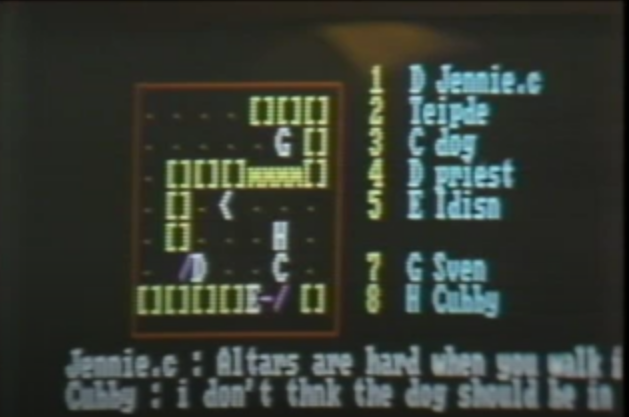

Woods said that Kesmai was an example of a multi-user game. Several people could be online playing any one game simultaneously. These weren’t arcade-type games with stunning graphics. The visual display had to consist of the basic characters that could be sent across the phone lines to all types of computers. So angle brackets, carets, dashes, and dollar signs represented doors, altars, or treasures (see below). But graphics were not the selling point of these multi-user games. Orkin told Woods that it was different–and fun–to do it this way.

Imagination was a big part of these games, Woods noted. Players could take on the identities of their alter egos. Getting hooked on this sort of game could be expensive, she added, but there were plenty of people willing to make that investment. Otherwise, CompuServe wouldn’t be planning to offer more than the 30 online games it currently made available.

Advanced Flight and Golfing Sims

Ned Lerner and Jon Correll joined Cheifet and Kildall for the final segment. Lerner was a game designer with Electronic Arts. Correll was a product development manager with Accolade, Inc.

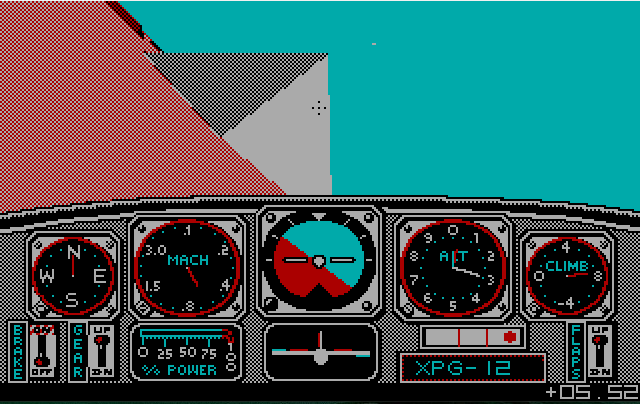

Lerner developed Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Trainer for EA. Kildall asked about the difference between a “flight trainer” and a “flight simulator.” Lerner said Flight Trainer had more emphasis on instruction than previous programs. For instance, the game included a flight instruction sequence developed by a professional flight instructor.

Kildall, himself a licensed pilot, asked for a demonstration. Lerner pulled up a demo of an F-18 Hornet on the PC version of Flight Trainer (see below). The plane started inside of a hangar. Lerner powered up the plane and conducted a test flight. The game’s landscape was a “fantasy” dotted with pyramid-shaped buildings. Lerner crashed the plane during the demo, which brought up a message from a digitized image of Chuck Yeager himself.

Continuing the demo, Lerner showed a “formation flying” mode where the goal was to fly an SR-71 Blackbird in formation with other planes. Kildall asked how much Flight Trainer actually helped someone learn to fly an airplane. Lerner said if you didn’t know much about flying, the program could teach you how the plane handled and how the instruments worked. So it might save you 50 hours of classroom time.

Cheifet asked what role Chuck Yeager–a retired Air Force brigadier general who became the first pilot to break the sound barrier in 1947–actually played in the design of Flight Trainer. Lerner noted that Yeager was the world’s most famous pilot. He helped EA pick the airplanes used in the program. Yeager also helped setup the training portion of the program. Kildall asked what other planes could be simulated in Flight Trainer. Lerner said the program included everything from World War I-era plans to experimental test planes.

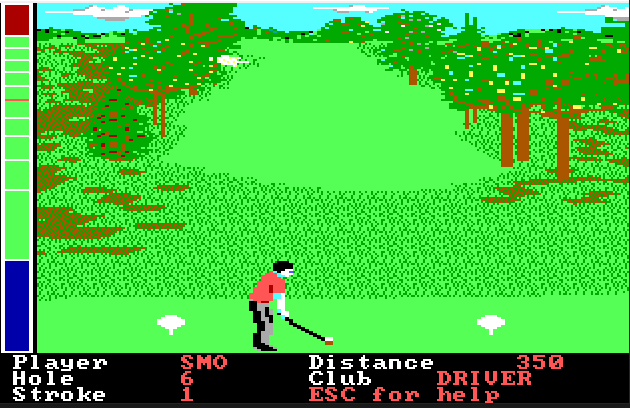

Turning to Correll, Cheifet asked how you simulated golf on a computer using his company’s program, Mean 18. Correll said it was probably a little easier than what Lerner did with Flight Trainer. Mean 18 certainly didn’t require as much concentration to play.

With that, Correll provided an extended demonstration of Mean 18 on the PC (see below). He showed the main menu, which gave the player several options, such as practicing on a tee or green, or going right into the full game. He resumed a game that he previously started on the Pebble Beach Golf Links, one of the real-world golf courses included with the game. The player could use either the professional or regular tees. (The regular tees are closer to the hole.)

Correll played the 18th hole at Pebble Beach. He explained the computer recommended a golf club for each shot based on the remaining distance to the hole. The player could also press Escape to bring up a list of all of the various keyboard commands. But the basic game play only required three taps of the space bar to hit the ball. The first tap started the player’s back swing. The second started the down swing. And the third determined if the player hit the ball straight or hooked it to the left or sliced to the right. Correll explained this setup was easy for new players to learn yet still required a good degree of timing to get the shot right. He then continued a fairly lengthy description of completing the hole, which I won’t recap.

Cheifet noted there were four built-in courses that came with Mean 18. But it was also possible for the player to design their own courses. Correll said that was correct. Mean 18 came with a “course architect” that allowed players to either create a new course or modify an existing one.

Macintosh Gaming Just Wasn’t That Profitable

Strategic Conquest was the first game published by PBI Software, Inc., a company I discussed in the previous post. To briefly recap, William Low started PBI Software to develop third-party hardware and software for the Apple II and later the Macintosh. Strategic Conquest was a Macintosh clone of a game called Empire originally developed on the PLATO computer network.

Peter Merrill created Strategic Conquest on an Apple Lisa between 1984 and 1985 to run on the original Macintosh. Merrill began his career as a software engineer for the defense contractor Lockheed Martin. His brief foray into developing games included one other PBI title, a shooter called Feathers & Space, which came out in 1985. Around the time this episode aired in late 1987, Merrill joined Software Publishing Corporation, where he worked on Harvard Graphics, a business applications program. In 1991, Merrill joined Adobe, where he would spend the next three decades working as a manager and technical lead on several of the company’s flagship products, including Photoshop and Illustrator. Since 2012, Merrill has served as a principal scientist at Adobe focused on digital imaging and video projects.

As for Strategic Conquest, it had a longer life than PBI Software. After Low closed PBI in 1990, the rights to Strategic Conquest passed to another small Macintosh-focused game developer, Delta Tao Software. Joe Williams and Tim Cotter founded Delta Tao in 1989 after successfully publishing an inexpensive Macintosh paint program. They continued to revise and expand Strategic Conquest through a 256-color 4.0 release in 1998.

Delta Tao also acquired the rights to another Macintosh game demonstrated in this episode, Silicon Beach Software’s Beyond Dark Castle. The sequel to Dark Castle–which Paul Schindler reviewed back in September 1987–Beyond Dark Castle was considered a critical and commercial triumph. But it would also prove to be Silicon Beach’s swan song when it came to the micro-niche of 1980s Macintosh gaming.

Journalist and video game historian Richard Moss published The Secret History of Mac Gaming in 2021, which contained an extended history of Silicon Beach Software. Charlie Jackson founded Silicon Beach in 1984. As Moss explained, Jackson was a former Marine who dreamed of being a national team athlete–he didn’t care which sport. He ultimately settled on shooting, but he needed to make money to train. So he decided to start a software company focused on the new Macintosh computer.

Since Moss was no programmer, he hosted a local users group meeting at his San Diego home, where he met Eric Zocher. At the time, Zocher was studying computer science at the University of California, San Diego. Zocher agreed to work for Moss on the spot.

But as Peter Merrill had learned when creating Strategic Conquest, programming for the Macintosh in 1984 meant buying an expensive Apple Lisa, since that was the only development system available. Jackson used his life savings to buy the Lisa. And much like his PBI counterpart William Low, Jackson was happy to hire teenagers to program his games–in this case a high school student named Jonathan Gay, who developed Silicon Beach’s first released game, Airborne!

Zocher created the sound effects for Airborne!, which Moss noted “drew lots of positive attention and buzz” when the game was demonstrated publicly at the first Macworld Expo in 1985. The game proved a hit at the show and with the small-but-loyal base of Macintosh users. Silicon Beach subsequently sold enough copies of Airborne! to establish itself as a legitimate developer.

Dark Castle came about after an experienced game designer named Mark Pierce joined the company. Pierce was one of the co-founders of MacroMind, a company I discussed in a recent post for its work in developing another early successful Macintosh program, VideoWorks II. According to Moss, Pierce left MacroMind after co-founder and president Marc Canter sold part of the company to his father-in-law in exchange for a badly-needed influx of capital, which of course diluted Pierece’s ownership stake.

Initially, Jackson hired Pierce to create some animations and graphics that Silicon Beach could use to attract their own outside investors. Pleased with this work, Jackson and Zocher then pitched Pierce on their idea for a new platform game, which was loosely based on a “short-lived TV show about a family that stumbled through a portal, and a military board game called TimeTripper.” Pierce thought this idea was “stupid and incoherent” and proceeded to create a storyboard for his own game, which became Dark Castle.

To make a long story short, Pierce took over the game design while Zocher handled the digitized sound effects, which included one of the earliest examples of voice acting in a computer game. (It also pioneered the use of the WASD control scheme, which was probably necessary since the original Macintosh had no arrow keys.) The finished game came out in 1986 to glowing reviews. Moss said that by the start of 1988, Silicon Beach had sold 30,000 copies of Dark Castle and the game would remain a best-seller on Macworld’s list of entertainment software for more than three years. Beyond Dark Castle–essentially a more difficult version of the original–enjoyed similar acclaim and commercial success.

Beyond Dark Castle would also be the final Silicon Beach game. Moss explained it came down to simple economics: Silicon Beach made far more money selling various graphics and utility programs for the Macintosh, such as Digital Darkroom and SuperPaint, than it did on games. Jackson saw where the wind was blowing and decided to shift focus away from games. And it paid off. In January 1990, Aldus Corporation purchased Silicon Beach Software from Jackson. That August, Aldus brought in Stephen Cullen, a former Software Publishing Corporation executive, to replace Jackson as general manager of what was now its Silicon Beach subsidiary.

The exact terms of the deal were not disclosed publicly at the time, but according to Moss, Jackson sold his company “for exactly the amount he needed in order to train in international style rapid-fire pistol shooting full-time.” He would go on to complete that training and ultimately earned a spot on the U.S. national team for rapid fire pistol shooting in 1993 and 1994. Years later, Jackson created a new software company, also named Silicon Beach Software, which develops a 2D vector drawing program for Windows 10 machines.

As noted above, the rights to Dark Castle, like those of Strategic Conquest, ended up with Delta Tao Software. Delta Tao produced a full-color version of the game in the 1990s. A sequel, Return to Dark Castle, languished in development for several years before it was finally released in 2008 by Z Sculpt Entertainment.

Accolade’s Journey from Sports Game Darling to Bobcat-Fueled Mania

Rex Bradford developed the golf game Mean 18. Bradford got his start as a programmer with the board game company Parker Brothers, which entered the Atari VCS (2600) cartridge market in 1981 at the height of that system’s popularity. Bradford co-developed The Empire Strikes Back, a VCS game based on the popular Star Wars sequel, which Parker Brothers had licensed the rights to from Lucasfilm.

Bradford then had a brief stint at Activision before starting his own development company, Microsmiths, which he formed with a couple of former Parker Brothers colleagues. Mean 18 would prove to be Microsmiths biggest hit. Bradford recalled the development history in a 1997 interview with Tim Duarte:

At Microsmiths, what we did was a combination of original designs and “ports” of games for other publishers from one game system to another. While doing that work, I wrote Mean 18 on nights and weekends in my spare time just as a labor of love, because I had always been a golf fanatic and wanted to do a computer golf game. I went to the [Consumer Electronics Show] in January 1986 with a nearly-completed game of Mean 18 and Accolade among other companies were extremely interested in it. I struck a deal with them, finished up the game, and they published it and that was a very big game for several years.

Accolade, Inc., was founded in July 1985 by two programmers–Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead–who themselves had a long history with the VCS. Miller and Whitehead both joined Atari, Inc., in 1977 to program first-party games for the console. They subsequently joined fellow Atari programmers David Crane and Larry Kaplan in leaving the company at the end of 1979 to form the first third-party developer, Activision.

Initially, Activision saw great success with its own VCS releases. But then the North American home video game market collapsed in 1983–largely because of Atari–and while Activision managed to weather the storm and even held a successful initial public offering, the shift in the company’s fortunes led to the departure of both Miller and Whitehead. As Whitehead recounted in a 2005 interview with Digital Press:

We owned stock, [Activision CEO Jim Levy] had a little more than us designers, but the [venture capitalists] got the controlling interest. We were insiders, so selling stock was a no-no, but the market had turned and our stock was a tenth of what it was…and morale wasn’t so good. We felt that diversification was a big part of the problem and computers, such as the [Commodore] 64, were a growing segment. And we weren’t naive kids anymore– opportunity knocked!

To that end, Miller and Whitehead decided their new company, Accolade, would squarely focus on computer games rather than consoles. Miller told Computer Gaming World in 1986, “We started the company first and then we thought of game ideas for awhile before actually starting.” Sports games quickly emerged as the company’s specialty, which fit the co-founders backgrounds well. Miller had previously developed basketball and ice hockey games for the VCS, while Whitehead had done the same with boxing and skiing.

In 1985, Accolade released Hardball!, a Commodore 64 baseball game designed by Whitehead, which sold 80,000 copies in its first year. Accolade followed that up with a boxing game, Fight Night, before publishing Microsmiths’ Mean 18 for MS-DOS computers in March 1986. In its first four months, Mean 18 sold over 20,000 copies, according to the Sacramento Bee, and Accolade would port it to a number of other platforms, including the Atari ST, Amiga, and Apple IIgs. By August 1988, Mean 18 was certified “Gold” by the Software Publishers Association, meaning it had sold over 100,000 units across all platforms.

And while video and computer games based on golf were hardly new even in 1986, Mean 18 was one of the first to feature a 3D perspective and employ the now-common three-click method for swinging the club. Accolade was also savvy in marketing a series of standalone expansion disks–the precursor to modern DLC–containing additional golf courses based on real-world venues.

Accolade followed up Mean 18 with Jack Nicklaus’ Greatest 18 Holes of Major Championship Golf, which was not developed by Microsmiths but effectively functioned as a sequel to Bradford’s game. According to Baltimore Evening Sun writer Michael Himowitz, the Nicklaus game played “much like Mean 18, although I think Accolade made putting a little easier in this version.” And unlike Mean 18, which came with four complete courses as part of the base game, Nicklaus only featured a single course, which was made up of individual holes taken from popular tournament courses like Pebble Beach Golf Links in California and the Old Course at St. Andrews in Scotland. (Obviously, Accolade also sold several expansion disks with additional courses.)

Accolade itself was also in the midst of a leadership transition during the 1987-88 period when this Chronicles episode aired. Miller and Whitehead initially recruited Thomas Frisina, who previously headed one of Atari founder Nolan Bushnell’s many failed post-Atari ventures, as the founding CEO of Accolade. But Frisina resigned as Accolade CEO in 1987 to form his own game development company, Three-Sixty Pacific, which focused on wargames. (Three-Sixty actually did ports of Silicon Beach’s Dark Castle for various non-Macintosh platforms.) Miller then took over as CEO for several months until Allan Epstein assumed the position.

Epstein’s tenure at Accolade was defined by the company’s move into home video game consoles. That didn’t happen immediately, however, even as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) revived the dormant market with retailers in 1986 and 1987. A stumbling block for Accolade was Nintendo’s strict control over the licensing of third-party NES games–enforced by a hardware “lockout chip.” Dan Gutman, writing in the Arizona Republic in December 1988, reported that Accolade applied for a license the year before but was turned down by Nintendo. And even after Nintendo reconsidered, it insisted on restrictions that Epstein considered unfair, specifically limits on the number of titles the company could release and the total number of cartridges that could be manufactured (by Nintendo itself). In the end, Accolade ended up sub-licensing a handful of its existing titles to other publishers who ported them to the NES, including a 1990 conversion of the original Jack Nicklaus golf published by the Japanese developer Konami.

But Accolade was still determined to get Accolade onto consoles as a direct publisher with the Sega Genesis, which Sega Enterprises Ltd. released to the North American market in 1989. Sega initially tried to copy Nintendo’s third-party licensing restrictions. And while Accolade entered negotiations with Sega, talks broke down when Epstein balked at Sega’s demand that it manufacture all of the actual cartridges (as Nintendo did with the NES). But rather than walk away or rely on licensing its games to other publishers, Accolade decided to reverse engineer the Genesis.

This was not an uncommon practice in the video game market. Indeed, Activision had to reverse engineer the Atari VCS when it developed its first games back in 1980. And Accolade wasn’t even the only company to reverse engineer the Genesis. Electronic Arts, which also chaffed at the licensing restrictions of Nintendo and Sega, did the same thing with the Genesis.

Sega ended up suing Accolade over its reverse engineering, however, alleging that Accolade violated Sega’s copyrights and trademarks. Sega’s case hinged on what it called the “trademark security system” (TMSS) a feature incorporated into a later revision of the Sega Genesis known as the Genesis III. TMSS checked for the word “SEGA” at a specific memory location on an inserted game cartridge. If the “SEGA” was present, the game was considered Genesis-compatible and booted with a title screen that said, “Produced by or under license from Sega Enterprises Ltd.”

When Sega demonstrated the Genesis III at the winter 1991 Consumer Electronics Show, Accolade realized its cartridges no longer worked properly. So Accolade conducted a second round of reverse engineering, which was described in this 1992 opinion from the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco:

During the reverse engineering process, Accolade engineers had discovered a small segment of code — the TMSS initialization code — that was included in the “power-up” sequence of every Sega game, but that had no identifiable function. The games would operate on the original Genesis console even if the code segment was removed. Mike Lorenzen, the Accolade engineer with primary responsibility for reverse engineering the interface procedures for the Genesis console, sent a memo regarding the code segment to Alan Miller, his supervisor and the current president of Accolade, in which he noted that “it is possible that some future Sega peripheral device might require it for proper initialization.”

In the second round of reverse engineering, Accolade engineers focused on the code segment identified by Lorenzen. After further study, Accolade added the code to its development manual in the form of a standard header file to be used in all games. The file contains approximately twenty to twenty-five bytes of data. Each of Accolade’s games contains a total of 500,000 to 1,500,000 bytes. According to Accolade employees, the header file is the only portion of Sega’s code that Accolade copied into its own game programs.

In 1991, Accolade released five more games for use with the Genesis III, “Star Control”, “Hardball!”, “Onslaught”, “Turrican”, and “Mike Ditka Power Football.” With the exception of “Mike Ditka Power Football”, all of those games, like “Ishido”, had originally been developed and marketed for use with other hardware systems. All contained the standard header file that included the TMSS initialization code. According to Accolade, it did not learn until after the Genesis III was released on the market in September, 1991, that in addition to enabling its software to operate on the Genesis III, the header file caused the display of the Sega Message.

In April 1992, a federal judge issued an injunction against Accolade, holding that it had unlawfully infringed Sega’s copyrights and trademarks, and ordered the company to recall all of its “infringing games” within 10 business days. The Ninth Circuit stayed that order and later reversed the district court and dissolved the injunction. Judge Stephen Reinhardt, writing for a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit, held that “when there is no other method of access to the computer that is known or readily available to rival cartridge manufacturers, the use of the initialization code by a rival does not violate the [Lanham] Act even though that use triggers a misleading trademark display.” In other words, Sega could not force unlicensed developers who lawfully reverse engineered the Genesis from copying the TMSS code so that their cartridges would work, even though copying that code displayed a “false” trademark message.

Accolade and Sega ended up reaching an out-of-court settlement in May 1993. Under the deal, Accolade finally became a third-party licensee of Sega. But it was something of a Pyrrhic victory, as Accolade suffered a significant decline in sales during the two-year litigation . During this time, Allan Epstein had also left the company and Alan Miller again took over as CEO. Peter Harris, the former CEO of the FAO Schwarz toy store, would take over as CEO of Accolade for a year before turning over the reigns to chief operating officer Jim Barnett in 1995.

It was also in 1993 that Accolade attempted to launch its own mascot-themed console game franchise with a bobcat character known as “Bubsy.” Accolade published Bubsy in: Claws Encounters of the Funeral Kind on both the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Genesis. The pre-release hype for Bubsy was substantial and, in retrospect, probably excessive. For example, London’s Daily Mirror ran a preview proclaiming, “The ultimate video game hero is out to zap Mario and SOnic and reign supreme as the fans’ No. 1. His name is Bubsy Bob Cat–and he aims to steal their thunder AND their sales.” An Accolade spokesperson further bragged, “We have spent a fortune researching what players want in a character and left nothing to chance.”

Accolade followed up that first Bubsy game with three sequels, none of which managed to live up to the initial hype. While the company continued to churn out games–notably its trademark sports titles–by the late 1990s the privately held Accolade struggled to stay afloat. In 1997, Electronic Arts became an investor in Accolade and took over its distribution. Two years later, in July 1999, French video game publisher Infogrames Entertainment SA purchased Accolade for $50 million (plus the assumption of another $10 million in debts). Infogrames later acquired the rotting corpse of Atari and subsequently assumed its name, becoming Atari SA. When that company filed for bankruptcy in 2013, the Accolade trademark and several of its games were sold off to pay creditors.

But because you cannot kill Atari with conventional weapons like bankruptcy, the company somehow survived, and in 2023, the most recent incarnation of Atari re-acquired the Accolade name and many of its games, including the Bubsy series and Alan Miller’s original Hardball!

Lerner’s Adventures Through the Looking Glass

Interestingly, when original Mean 18 developer Rex Bradford closed his company Microsmiths in the mid-1990s, he ended up joining Looking Glass Studios, which was co-founded by a guest from this episode, Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Trainer developer Ned Lerner. Looking Glass actually grew out of Lerner’s first company, Lerner Research, which developed the flight simulator for Electronic Arts.

Lerner graduated from Connecticut’s Wesleyan University, where he met fellow student Paul Neurath, who founded Blue Sky Productions. Blue Sky famously developed the landmark 1992 game Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss and its sequel for Origin Systems, which was later acquired by Electronic Arts. Also in 1992, Lerner and Nuerath decided to merge their companies, naming the combined entity Looking Glass Studios. That company shut down in May 2000.

While still working at Looking Glass, Lerner co-founded another startup, Multitude Communications, which developed Firetalk.com, an early attempt to build an online voice chat platform. The service only lasted until March 2001 after the parent company–later renamed Firetalk, Inc.–reportedly burned through $45 million in venture capital funding.

In the 2000s, Lerner returned to his game development routes. He had a brief stint as chief technology officer of EA’s Maxis subsidiary in 2003 before joining Sony Worldwide Studios as its director engineering. In 2017, Lerner left Sony to start a new venture, Hearo.Live, a mobile app that lets users watch television programs together.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was first broadcast the week of December 23, 1987.

- Stewart Cheifet recorded the cold open for this episode at the offices of PBI Software in Foster City, California, which as I noted in the previous post was just down the street from the College of San Mateo where Computer Chronicles taped.

- Paul Schindler’s software review for this episode was Infocom’s Leather Godesses of Phobos ($50), which had recently been ported to the Macintosh.

- Eriz Zocher left Silicon Beach Software in 1989 to join Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computer, where he oversaw development support for the NeXTSTEP operating system. A year later he joined Adobe Systems as its vice president of engineering, overseeing the applications division. He would go on to co-found a few different startups in the late 1990s and early 2000s before going to work for Microsoft, where he stayed for 10 years before becoming an independent developer in 2017.

- Gilman Louie created Falcon while completing a business degree at San Francisco State University in the early 1980s. He founded Nexa Corporation to publish the game. Nexa later merged with Coloardo-based Spectrum Holobyte, with Louie becoming the latter’s chairman. Falcon was a major commercial and critical success for the company, winning three Software Publishers Association awards in 1988. Spectrum Holobyte developed a number of sequels, with Falcon 4.0 being the final release in 1998. By that point, Spectrum Holobyte had acquired another developer of military combat simulators, MicroProse, and assumed its name. Hasbro Inc. then purchased MicroProse in 1998, and after the sale closed further development on the Falcon series ceased. But in May 2023 MicroProse–now an independent company again–announced it had re-acquired the Falcon series rights and planned to develop Falcon 5.0 in the future.

- The Other Side was published by Tom Snyder Productions, Inc. The company’s founder and namesake–no relation to the former late-night talk show host–was a science and math teacher at a private school in Massachusetts in the late 1970s. In 1980, he founded Tom Snyder Productions with $30,000 in startup capital from the father of one his students. The company originally focused on developing educational software for the Apple II. Snyder later expanded into television production, most famously developing the Comedy Central animated series Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist. Bolstered by that show’s success, Snyder sold his company to Canada-based Torstar Corporation in 1996 for an undisclosed amount of cash. Torstar later sold Tom Snyder Productions–renamed Soup2Nuts in 1999–to Scholastic Corporation in 2001 for $9 million. Scholastic closed Soup2Nuts in 2015.

- Kelton Flinn and John Taylor created the multi-user dungeon game Island of Kesmai while attending the University of Virginia. Jimmy Maher of The Digital Antiquarian delved into the game’s development in some detail. Flinn and Taylor started a games company, also named Kesmai, which published a number of other early online multiplayer games such as Megawars and Air Warrior. News Corporation purchased the Charlottesville, Virginia-based Kesmai Corporation in 1994 for undisclosed terms. (News Corp. also owned the online service Delphi at the time.) News Corp. later sold Kesmai to–guess who–Electronic Arts in 1999. EA folded Kesmai’s online gaming technology into EA.com and closed the Charlottesville studio in 2001.

- When Gary Kildall asked about the difference between a “flight simulator” and a “flight trainer,” I assume he was needling Jon Correll about the fact EA had to change the name of its game after Microsoft–which published Microsoft Flight Simulator–objected to the use of the word “simulator” in a competing title.