Computer Chronicles Revisited 89 — The Macintosh SE and the Macintosh II

When you think about it, the original Apple Macintosh was a ridiculous computer. It had a 9-inch monochrome display that was tiny even by 1984 standards. There were no expansion slots, which was a standard feature of most personal computers, including the venerable Apple IIe. And there was no way to add a hard drive without going to a third-party provider such as General Computer Corporation.

So by all rights, the Macintosh should have been a failure like Apple’s two prior attempts to enter the business computing market–the Apple III and the Lisa–but it wasn’t. This was largely thanks to the work of third-party hardware developers like GCC–but especially third-party software companies like Aldus and Adobe, which made the Macintosh the go-to in the newly emerging field of desktop publishing.

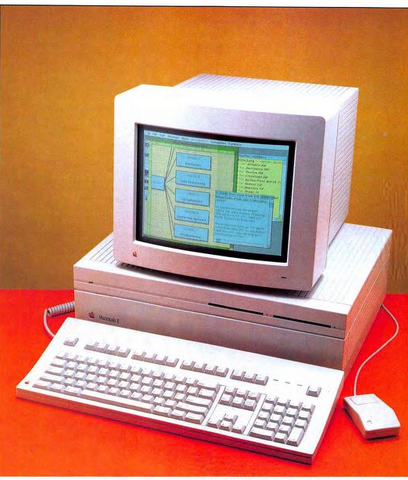

But by 1987, Apple realized the business market wasn’t going to give up the comforts of expansion slots and color displays to live inside Steve Jobs’ mystery box. In the wake of Jobs’ departure, Apple CEO John Sculley and his team moved quickly to introduce a new, more business-friendly machine in the form of the Macintosh II while “rewarding” Mac loyalists with a rebuilt-from-scratch revision of the classic model, the Macintosh SE.

These two new Macs were the featured subject of this next Computer Chronicles episode from May 1987. Stewart Cheifet opened by showing Gary Kildall an add-on board for the new Macintoshes. Cheifet quipped that the Macintosh II actually looked an awful lot like an IBM PC/AT. And if you looked at the new IBM PS/2 computers, they resembled Macintoshes. Had the two computer giants finally come together and agreed on what a personal computer should be? Kildall replied they’d come together to try and compete for the same market. Apple learned from IBM’s open architecture where third-party suppliers could offer expansion boards. At the same time, IBM learned from Apple that customers wanted a more user-friendly graphical interface and desktop publishing capabilities. So while the two companies hadn’t come together on the same hardware, they had come together on the underlying philosophy.

Would Businesses Use Macs for More Than Desktop Publishing?

Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment, which focused on the use of the new Macs in business. Woods said the history of the Macintosh was similar to that of the personal computer industry–full of victory and defeat, of approval and rejection. Today, with Mac sales booming and two new machines joining the line, Apple seemed to be pushing harder than ever to make the Mac a major contender in the business world.

Mark Alan Winter, an industrial designer who owned the firm Cephalon, Inc., told Woods that the Macintosh marketplace had grown from the hobbyist computer users and hackers who were fascinated by the machine’s potential to now seeing growth in the business world where that potential had been realized. The applications that had come out for the Macintosh had finally begun to approach what the machine was capable of. In contrast, when the original Macintosh was released in 1984, there were no serious business applications available, Winter noted.

Woods said that Winter’s firm specialized in Macintosh graphics. It might not be on the Fortune 500 list yet, but it did have some big clients, and Winter said there was a growing acceptance of the Macintosh in corporate offices. He said that it was usually a company’s design department or a “few unorthodox managers” who saw the world in their own way who brought Macintoshes into their offices. In the case of a design group, that made perfect sense.

Indeed, Woods said, the Mac’s talent for desktop publishing got it through the corporate gates. But once inside, there were new obstacles to overcome. Winter said that in the past, a company’s information systems department was a “central repository” and control point for the way information flowed in the company. Now you were proposing to bring in intelligent, independent workstations that could perform tasks independently of a central host computer–and which could communicate with one another independent of any centralized network. That had far-reaching implications for the traditional corporate power structure.

SE Made Concessions to User Demands for Expansion Slot, Hard Disk

Charlie Oppenheimer, the product manager for the Macintosh SE at Apple, joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio to demonstrate the new machine. Kildall noted that when he bought his first Mac a few years back he found a couple of screws in the back that he couldn’t open with a regular screwdriver. Why was the original Macintosh a closed architecture? Rather than just say “Steve Jobs,” Oppenheimer offered a more diplomatic, if still condescending, reply. He said that back in 1984 Apple had a strong sense of what their customers were going to need, and there was no reason for most people to want to open up the machine, so it was set up to be “dealer serviceable” only.

So why the change in philosophy, Kildall asked. Oppenheimer said that both the SE and the Macintosh II represented a foundation on which developers could be more creative in adding expansion hardware and application software.

Turning to the SE on the desk, Oppenheimer explained some of the differences from the older Macintosh models. He noted that while the base unit still came with just one floppy disk drive there was an option to add either a second floppy drive or a hard disk inside the machine. This particular unit had the hard disk option. Oppenheimer turned the machine around to show the ports on the back, which were similar to those of the prior models. In addition, there were two Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) ports, which was Apple’s new standard connectors for keyboards, mice, and other input peripherals. (The Apple IIgs, released the previous fall, was the first machine to feature ADB ports.)

Oppenheimer then pulled off the top case of the SE to show the internals. He pointed out that the SE only shared one hardware component with the previous models, and that was the CRT display. Everything else had been completely redesigned. He noted there was a more heavy-duty power supply that used 75 watts (as opposed to 50 on the previous models). There was also a fan–the bane of Steve Jobs’ existence both before and after Flash–which was necessary to accommodate the hard disk. The hard drive itself was a 20 MB model using a SCSI connector. And there was a single accessory access port for mounting connectors for an expansion card.

Turning the open SE on its side, Oppenheimer next showed off the logic board, which he pulled out and showed Cheifet and Kildall. He said the board came with 1 MB of RAM standard, which could be expanded to 4 MB like the Macintosh Plus. The Motorola 68000 microprocessor was also the same as on the Plus and ran at the same speed. The system ROM had been expanded, however, from 128 KB to 256 KB.

Oppenheimer also pointed out a new gate array that incorporated 19 chips from the Plus, which he said was the key to performance improvements. He claimed the SE had a 15 to 20 percent improvement in overall processing speed, and SCSI performance was up to 2 times faster. Focusing on the expansion slot, he showed a General Computer card, a 68020 accelerator, which plugged on top of the motherboard.

Oppenheimer noted there were four types of expansion boards that Apple saw being available for the SE: accelerator cards, math co-processors, communications cards, and large screen adapters. Kildall asked how you could use multiple different cards given there was only one expansion slot. Oppenheimer acknowledged the issue and said the solution was for developers to create multi-function cards. He said the most popular option would likely be an accelerator card combined with a large-screen adapter.

Cheifet noted that even though the SE had an expansion slot, the manual cautioned users not to install a board themselves–they had to take their machine to a dealer. Oppenheimer said while it was easy for him to take apart the SE, as he just did it, it wasn’t the sort of thing that the average user would be good at doing. So to insure the most reliable installation of the board, Apple felt it was best to have a dealer do it instead. (To be clear, all Oppeneimer did was remove the back of the case, pull out the motherboard, and plug a card into it.)

Kildall asked about the cost of the SE compared to a standard Macintosh. Oppenheimer said the Macintosh Plus still retailed for $2,199. The SE with two floppy drives would sell for $2,899, and with the hard drive option, $3,699.

Cheifet pointed out that many current Macintosh Plus owners were upset there was no way to upgrade their existing machines to an SE. What was Apple’s reasoning behind that? Oppenheimer said that while Apple considered an upgrade path, in order to provide for an internal hard disk and expansion slot there was no way to do so via an upgrade. He reiterated his earlier point that every component of the hardware was different from the Plus except for the screen. So an upgrade would have been too laborious.

Looking Inside the Mac II’s Open Architecture

Didier Diaz, the product manager for the Macintosh II at Apple, joined Cheifet, Kildall, and Oppenheimer for the next segment. Kildall opened by asking Diaz about the target market for the Mac II and how it differed from the SE. Diaz said that with its increased power, the Mac II was targeted at the higher end of the current marketplace, notably the business community. He also saw the Mac II penetrating new markets such as engineering and universities, in part because it could run UNIX as well as the native Macintosh operating system.

Kildall asked for a demonstration of the Mac II’s “open architecture.” Diaz had a Mac II unit in front of him. He explained you just had to pull two latches in the back to open the machine up. This made it possible for customers to add cards in the machine quite easily. (I guess you didn’t need to take the Mac II to the dealer to do the upgrade for you?) He removed and showed off the Mac II’s video card, which drove both monochrome and RGB color monitors. The video card had its own configuration ROM, which was part of the NuBus standard used in the Macintosh II. When the machine booted, it scanned all of the expansion slots for these ROMs, so the customer didn’t have to manually configure any DIP switches. The video card also had a built-in lookup table with 16 million entries representing 16 million possible colors, although the Mac II could only display up to 256 of them at one time.

Continuing his disassembly, Diaz pulled out the chassis of the Mac II, which contained the hard disk and floppy disk drive mounted on a metal plate. He said the Mac II could be configured with a 20 MB, 40 MB, or 80 MB hard disk. The access time on the 40 and 80 MB drives was under 30 milliseconds, which could transfer up to 1.2 MB of data per second over the SCSI interface.

Diaz next showed off the 250-watt power supply and the logic board. He pulled out the motherboard and showed the Motorola 68020 microprocessor and an included co-processor. This was the next-generation revision of the 68000, the older processor being the one in the Macintosh Plus and SE models. The 68020 was a full 32-bit processor like the Intel 80386. Diaz claimed the 68020 offered a speed increase of up to 4 times over the Mac Plus. The math co-processor also came as a standard feature.

The Mac II had six expansion slots. Diaz said that a card plugged into any one of these slots could “take over” the entire machine. So for example, it would be possible in the future to plug in an expansion board with an updated CPU–say a hypothetical Motorola 68030–and it could run the computer. Diaz noted the Mac II also had the standard Macintosh ports, including the new ADB ports.

Cheifet asked for a software demonstration of the Macintosh II. Using a second machine setup at the desk, Diaz opened a MacDraw document and showed how the increased speed of the 68020 allowed for more fluid motion in manipulating the image. He noted the demo unit had a 13-inch color display. (Apple also sold a 12-inch monochrome display.) To demonstrate the impact of having a math co-processor, Diaz ran a simulation that had the Mac II graph a complex equation. First he had the machine draw the graph without using the math co-processor, then with it. As you probably guessed, the plotting went much faster with the co-processor–up to 200 times faster, Diaz claimed. He said this increased speed would allow Macintosh software to get into areas where it couldn’t before due to a lack of horsepower. Now it would be possible to do tasks such as 3D modeling.

Looking at the monitor, Diaz pointed out the display’s resolution was high enough to be used for both black and white and color. He brought up a digitized color image of an Apple executive. This demonstrated the “full power” of the Macintosh II’s video card. He also brought up a computer-generated image to show off the computer’s ray tracing capabilities.

Cheifet asked about the price for the Macintosh II. Diaz said the entry-level price was $3,895. The color display version with a 40 MB hard disk would run about $6,500.

Third Party Developers Excited by New Macs

Wendy Woods returned for her final remote segment, which began with some B-roll of an Apple factory in Fremont, California. Woods said that while users worried about the availability of software for the new Macs, the problem was magnified for the software developers who risked losing money if a machine wasn’t successful.

Living Videotext was one of a few dozen companies that received prototypes of the SE and the Mac II, Woods said. The company immediately went to work upgrading its MORE idea processing program to utilize the Mac II’s color abilities. (Paul Schindler reviewed MORE in an episode that I recently covered.) But unlike decisions made in the past, Living Videotext said the choice to support the new Macs was easy.

Dave Winer, president of Living Videotext, told Woods that you had to look at it from two angles. One was the economics: Did you think the machine would be successful in the marketplace? Did it answer the needs the users had? The second angle was more emotional. As a Macintosh user himself, Winer said the Mac II was virtually everything he wanted on his wish list. He was excited to put one of those machines on his desk. So it was therefore important for his company to support the new computers.

Woods noted the Macintosh SE could run virtually all current Macintosh software. So there was no shortage of readily available programs. And developers saw the Macintosh II’s expandability as its ticket to success–an open road for other companies to develop add-on products and new software.

The End of the Steve Jobs Era?

For the final segment, Cheifet and Kildall held a round-table discussion with regular contributors Jan Lewis and George Morrow. Kildall asked Lewis which of the new Macs consumers should buy. Lewis said that if price was no issue, everybody would get the Macintosh II. But most users had to ask themselves what they wanted out of their system, and how long they wanted that system to last. Right now, the Macintosh SE was a very big seller. People who had been buying the Macintosh Plus were now buying the SE. And for something like doing desktop publishing right now, the SE was the better bet. But if you wanted expandability, the Macintosh II would give you many, many years of enjoyment.

Cheifet asked Morrow for his thoughts on the new Macs. Morrow thought the Mac II was an expression of market envy. Apple had seen IBM do well with the business market and the add-on manufacturers. Now Apple wanted a piece of that action. So they came up with a new bus and color capabilities. It was like a fantastic game of “musical chairs,” where everybody was moving over to the position of what everyone else was doing a year ago.

Cheifet asked Lewis about Apple’s efforts to cut into IBM’s lead in the business market. Was it going to work? Lewis said it was already working with respect to desktop publishing. Even though corporate executives said the Macintosh wasn’t on their list of approved computers, when you walked up and down the halls of their offices there were Macs present. So Apple already had a “wedge” into the corporate market, and the new machines would take them much further. Morrow added that Apple had also done an awfully good job at computer networking.

Kildall asked Morrow how the Intel 80386 stacked up against the Macintosh’s Motorola 68020 in terms of performance. Morrow said the two were very similar in terms of raw processing power. But based on early reports from actual users, there seemed to be a “lot more overhead” in the Macintosh II than there was in the current 386-based machines. So the effective speed of the 68020 was somewhat lower. But both processors had a lot of horsepower. And the engineering workstation market would now be an awfully exciting place for a machine like the Mac II.

In our “premature celebration” moment of the episode, Cheifet asked Lewis if the new open architecture approach to the Mac marked the “end of the Steve Jobs era for good.” Lewis said it was definitely the end of that era. On the other hand, the one problem Apple would have as a result of being more open was that there were now likely going to be Mac clones. In the long run, however, she thought Apple would still come out ahead.

U.S., Dutch Government Agencies Deal with Computer Problems

Cynthia Steele presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in September 1987.

- West German computer hackers tapped into NASA’s secret files. Steele said the attackers gained access to information on the Space Shuttle Challenger and managed to change data on at least 20 of the agency’s computers.

- RICOH announced a new combination photocopier and scanner that was the size of a book. Steele said the copier also featured a digital attachment that could store scanned images.

- The United States Army had a new Automated Intelligence Maintenance (AIM) system that helped it to repair helicopters, fixed-wing aircraft, and other equipment. Steele said that AIM was an “expert system” that asked Army mechanics yes-or-no questions, with the answers helping to diagnose problems. AIM only had a built-in vocabulary of 12 words for input, but an unlimited output vocabulary.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Dark Castle (Silicon Beach Software, $50), an action-adventure game for the Macintosh.

- Computer-related words made up the bulk of the new words in the most recent edition of the Random House Dictionary. Steele said the next largest category of new words related to food and cooking.

- Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, planned to launch a program that would use computers to teach written English to the school’s deaf students.

- The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Standards had a new computer system called Hazard1, which was used to assess and analyze house fires to help better prepare firefighters.

- A law enforcement agency in the Netherlands stopped using software to identify “most wanted” criminal suspects after it targeted innocent citizens instead.

SE Boosts Apple Revenues While Press Is Dazzled by Mac II’s Potential

Apple formally announced the Macintosh II and Macintosh SE at the Universal Studios Ampitheatre in Los Angeles on March 2, 1987. The less-expensive SE was, not surprisingly, the bigger attraction for consumers. In late April, Apple CEO John Sculley told the press that the initial orders for the SE were the “strongest for any new Macintosh product in Apple’s history.”

Indeed, by July 1987, Apple reported the SE now accounted for nearly half of the company’s third-quarter revenues and that profits were up 65 percent from the previous year. The Macintosh II, which formally shipped on May 1, was not as big of a seller, although it did help Apple with large corporate sales. For example, in October, news reports said Apple sold between 6,000 and 8,000 Macintoshes to General Motors–many of them Mac IIs–for use in the company’s front offices.

From a historical standpoint, the release of the SE and the Macintosh II marked the beginning of Apple differentiating its Mac line between high-end, expandable professional workstations and medium-range all-in-one machines. This market segmentation persists to the present day. The Macintosh II can be seen as an early forerunner of the Mac Pro, while the SE’s legacy lives on in with the iMac.

And like today’s Mac Pro, the Macintosh II was really a niche machine. Reviewers at the time took note of this. Richard O’Reilly and Lawrence Magid said in their review for the San Francisco Examiner that while the Mac II was “an exciting and powerful machine” it was “rather expensive for most business and personal applications.” Still, the “extra speed, expansion capability and state-of-the art design should keep this machine viable well into the next decade.”

The Apple press was understandably elated with the new Macs. Michael D. Wesley, writing for the April 1987 issue of MacUser, was particularly awed by the potential memory capacity of the Macintosh II:

Macintosh II comes with 1 megabyte of RAM in SIMMs, just like the Mac Plus. There is room on the motherboard for 8 megabytes using 1-megabit chips. But Apple, anticipating continued rapid developments in chip technology, made the machine capable of addressing up to 128 megabytes of RAM on the motherboard (using 16-megabit chips, which may be available in the 1990s). And it’s possible to build the RAM up to 2 gigabytes by filling the slots with RAM cards.

Those numbers are so staggering that they made me break out laughing when I first read the specs. What could anyone possibly do with 2 gigabytes of RAM? Nobody knows yet because the option has never existed, but it makes the imagination run wild with possibilities.

As I understand it, the Macintosh operating system at the time could not handle more than 128 MB of RAM. But it was theoretically possible to address up to 2 GB–although other sources said it was 4 GB–of RAM using UNIX, which was a fully 32-bit operating system.

And to clarify another point that Didier Diaz made during his demonstration, while the Macintosh II did have a video card capable of displaying 256 colors at once out of a total available palette of around 16.8 million, that was not the standard graphics option for the machine. The basic video card only had 256 KB of RAM and supported just 16 colors (or shades of gray) at one time.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of May 26, 1987. The “Random Access” segment was likely recorded in September 1987.

- Charlie Oppenheimer remained at Apple until 1993. He went on to serve as CEO of three tech startups that he later sold: Aptivia (renamed Vivamart), Digital Fountain, and Loggly. As of 2023, he’s working as a consultant and corporate adviser.

- Didier Diaz remained at Apple until 1997. His last reported executive position was in 2009 with Access Europe GmbH, an in-car infotainment software company.

- Mark Winter’s design company Cephalon was only in business for a few years. Among his company’s credited inventions was the “BodyFender,” which a newspaper article described as a “large magnetized rubber shield that you can sleep on the side of your car and peel off whenever you want.”

- Silicon Beach Software, the company behind the game Dark Castle, was actually more notable for its contributions to lower-end paint and graphics applications, such as SuperPaint and Digital Darkroom. Aldus Corporation, the parent company of PageMaker, purchased Silicon Beach in 1990 in an all-stock transaction. Aldus, of course, was later sold to Adobe Corporation.

- According to an Associated Press report, the West German “hackers” who accessed NASA’s computers were teenagers who “had no interest in the secret data.” Indeed, when they “realized the enormity of their discovery,” they turned to a local computer club in Hamburg for advice on what to do next. NASA claimed there was no classified information on the compromised machines.