Computer Chronicles Revisited 84 — Computer Sports World, Thoroughbred Handicapping System, and Pointspread Analyzer

On April 28, 1988, Mark Herbst of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, went to the offices of the Pennsylvania Lottery to redeem the winning “Super 7” ticket from a July 1987 drawing. Under lottery rules, the winner had one year to claim their prize. Herbst, a clerk at a video rental store, told the press that he had “found the winning stub in an old cigar box.” He said he played the lottery so frequently that he often forgot to actually check his tickets. It was only a news report a few days earlier about unclaimed lottery prizes that prompted him to see if he might have a winning ticket.

Some people at the lottery office thought Herbst’s winning ticket was sketchy. But the ticket’s computer validation code was accurate, so the lottery cut Herbst a $469,989.55 check for the first installment of his $15.2 million jackpot. But within hours, lottery officials confirmed their initial suspicions were correct: Herbst’s “winning” ticket was indeed a forgery.

Herbst immediately came clean to agents from the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office. He said that a friend, Henry Rich, approached him with the fake ticket and asked him to bring it to the lottery office. Rich worked for Control Data Corporation (CDC), the company that provided the Pennsylvania Lottery’s computer system. Rich managed to access a file containing a list of unclaimed jackpot and then used CDC’s computers to produce a duplicate of the winning ticket.

In a twist that would make Michael Scott proud, lottery officials realized that Rich’s ticket was a fraud because he printed it on paper that had been returned to the state from a lottery agent in Scranton. But the paper used in the actual winning ticket–which was claimed by a couple from New Jersey before the one-year deadline expired–came from a different part of the state.

After Herbst cooperated with the Attorney General’s office to trap Rich in a sting operation, both men later pleaded guilty to criminal charges. Herbst received a prison sentence of 2 to 4 years. Rich initially received a 5 to 10 year sentence, although an appellate court later ordered a new sentencing hearing after finding the trial judge failed to give reasons for part of his decision.

Was Picking Horses Like Picking Stocks?

The Pennsylvania Lottery scandal took place about a year after this next Computer Chronicles episode first aired. The subject of this episode was “computers and gambling,” and ironically, Stewart Cheifet mentioned another Pennsylvania Lottery scandal that took place several years earlier–and explained how CDC’s computer system was designed to help prevent any future attempts at lottery tampering.

But before we get to that, the episode began with Cheifet showing George Morrow, this week’s co-host, an early example of a specialized computer targeting gamblers, the Mattel Horse Race Analyzer. Cheifet explained that you could enter data from the Daily Racing Form, a newspaper covering the horse race industry, into the Analyzer and it would predict which horses were most likely to win.

Cheifet noted that using a computer to pick a winning horse was not much different than using a computer to figure out which stock was going to “win” on Wall Street. Morrow agreed, noting that people who recommended stocks performed much the same function as handicappers in horse racing. In both cases, computers were an analytical tool that helped you form judgments. Gambling also involved an element of pure chance, and in that respect computers were being used to help entertain people.

Some Casino Operators Remained Skeptical of Video Slots

Speaking of entertainment, Wendy Woods presented her first report from Reno, Nevada, the home of International Game Technology Corporation (IGT), one of the country’s biggest slot machine manufacturers. Over B-roll footage of the Harrah’s casino in Reno, Woods said that poker chips were increasingly sharing the gaming floor with microchips–especially in the slot machines.

Charles Mathewson, the president and CEO of IGT, told Woods that poker machines were a prime example of how computer chips had transformed the industry. For all intents and purposes, computerized poker machines didn’t even exist 10 years ago. But today they represented 34 to 36 percent of the Nevada market.

Woods noted that the machines produced at IGT had little in common with their clanking, mechanical ancestors. IGT’s slots were sophisticated personal computers controlled by an Intel microprocessor that featured special graphics and sound chips. The machines were even designed by computer.

Peter Dickinson, IGT’s vice president of engineering, explained that when a player put their money in a computerized slot machine and pulled the handle, the microcomputer inside was programmed to compute a random number using a 32-bit random number generator. The computer then took that random number and “divided it down” to a number within the range of the number of symbols on the reel strips in the slot machine. That then determined the outcome of the game.

Woods said that since the outcome of the game was determined electronically, the spinning reels were included merely to preserve the traditional external appearance of the slot machine. This was important to casino operators. Bob Bittman, IGT’s director of marketing, said that in some cases the electronics scared the operators away. For example, a slot machine that only used a video display to replicate the look of a traditional slot machine didn’t attract a traditional slots player. It was “too much” of a computer screen, Bittman said. But when the same electronic technology was used with poker machines, customers seemed to love it.

Concealed within the friendly interface of the electronic machines, Woods noted, was a high level of electronic security. This included an optical reader that could tell if a coin was being dropped in or being pulled out of the slot. There were also sensors that could detect if a door was open or someone had tampered with the reels. The electronic slot machines were also tied into a local area network that transmitted any discrepancies to a central computer room.

Woods said that at Harrah’s, a fully electronic slots game called “Megabucks” used the latest in fiber optics–and even satellite transmission–to tie hundreds of machines together to a central jackpot computer. As each coin dropped, the amount of the bet was transferred by fiber optic cable to the casino’s computer center. The mainframe then recalculated and sent the new jackpot information to an LED display on the casino floor. The same system operated between casinos around the state over a satellite link.

Keno was another game that had been radically changed by computer processing, Woods said. While paper tickets were still written out by the player, all data entry, number reading, and bet tabulation were done by computer, which could process the results of a game in about 22 seconds.

Woods added that Harrah’s machines were equipped with more than coin slots. The new generation of “one-armed bandits” was more like an automatic teller machine at a bank–with some important differences. You can’t make withdrawals or deposits, but the casino would issue personal identification cards to any interested customer.

Computers Offered Handicappers a Statistical Advantage

Robin Cobbey and Michael “Roxy” Roxborough joined Cheifet and Morrow for the first studio segment. Cobbey was president of Computer Sports World. Roxborough was the founder and president of Las Vegas Sports Consultants.

Morrow opened by explaining that Computer Sports World (CSW) was a database of sports statistics owned by Chronicle Publishing Company, the parent company of the San Francisco Chronicle. How did those two entities work together? Cobbey said that in the last several years, many newspapers had wanted to get involved in new forms of communication and database services. CSW was one of those companies that were out there in a good market and it was something the Chronicle wanted to pursue.

Morrow asked if CSW was a unique database. Cobbey said there were no other products exactly like CSW, which was an online database. Anyone with a computer and a modem or communicating terminal could connect via a local telephone call 24 hours a day.

Morrow turned to Roxborough, a professional oddsmaker, and asked if he used CSW. Roxborough said yes, it was an instrumental part of making the odds. He thought CSW was fantastic because it saved a lot of time that he previously spent making handwritten notes. The online database also helped with filing and organizing information.

Cheifet asked Roxborough how he kept track of sports statistics and numbers before there were online databases. Roxborough said that he “made do,” but he could do a much better job now with computers. Morrow asked if the database made Roxborough’s work more accurate. Roxborough said it did. He added that gamblers could also access CSW, so that was another reason he needed to keep on top of the technology. Morrow asked if there were others in the gambling business who used CSW as extensively as Roxborough. Roxborough reiterated that there were gamblers who used it.

Cheifet asked Cobbey for a demonstration of CSW, which she pulled up on a terminal connected by modem. The main menu consisted of a live listing of upcoming men’s college basketball games. By typing a three-digit code you could pull up information and statistics about a specific game. Cobbey selected a game scheduled for Sunday, February 22, 1987, between Georgia Tech and DePaul. Roxborough said the data showed DePaul was 13-0 at home this season. That would make DePaul, the home team, a pretty good favorite over Georgia Tech, even though the latter was considered a strong team in its conference. Conversely, Georgia Tech was only 6-6 in road games. Roxborough added that CSW showed each team’s record against the spread during the season and statistics from the last five games played.

Cheifet asked about using CSW to look at National Basketball Association games. Roxborough pulled up a box score from the previous evening’s (February 20, 1987) game between the San Antonio Spurs and the Dallas Mavericks. Roxborough said that when he studied a box score he wanted to know if all of the team’s starters played. In this particular box score, for example, all of San Antonio’s starters played but Dallas starting point guard Derek Harper didn’t appear in the game at all. That meant Roxborough would have to find out why. Cobbey said CSW also contained injury reports, which showed Harper had an infected toe and was expected to miss tonight’s game against the Golden State Warriors. Roxborough said he would have to make a slight adjustment in his line for that game.

Next, Cheifet asked about baseball. Cobbey pulled up CSW’s index of baseball statistics, which went back several years. Roxborough said the key stats he looked for with respect to baseball was how teams did against right-handed and left-handed pitchers respectively, and their performances in day games versus night games. Cobbey added that CSW worked with Roxborough’s company to provide odds on teams winning the pennant. Roxoborough said that for the upcoming 1987 season, the odds favored the two New York teams, the Yankees (7-2) and the Mets (7-5). (Roxborough was a bit off. Neither New York team won their respective division and the Minnesota Twins defeated the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1987 World Series. And the Twins were 30-1 underdogs in March according to CSW.)

Cheifet asked Roxoborough if there was any particular sport where the computer was a really big advantage. Roxoborough said college basketball because they had to chart and track 162 teams. There were thousands of variables and injuries to chart for every team.

An Electronic Brain for the Modern Racetrack

Wendy Woods returned with her final report, this time from the Golden Gate Fields horse racing track in Albany, California. Over B-roll of a traditional bugle “call to the post,” she said that while certain traditions at the track would never fall under the spell of technology, the business of race track betting had in many fields been automated to a level as sophisticated as the nation’s election system. Unlike the old days of just a few years ago, relay systems and tallying by individual clerks had been replaced by massive computerized betting systems.

At Golden Gate Fields, Woods said, the odds, race results, and up to $3 million in bets placed daily passed through seven continuously operating phone lines to the “brains” of the operation–a mainframe at the nearby Bay Meadows racetrack. Betters could still go face-to-face with humans for their wagers, but the clerks all used terminals linked up to the system. The more adventurous better could use a self-serve betting machine or the newest touch screen terminals. Players bet and collected with vouchers that could be used for an entire day of winning or losing.

Woods noted that even the tote board on the track was controlled and automatically updated by this one computer system. Marty Miller, a systems manager with AmTote, the company that ran the system, told Woods that computerized betting was not only efficient but honest as well. But Woods said things didn’t always go smoothly. She said that on the day that new cards were issued the system crashed. Golden Gate Fields officials had to soothe irate customers by issuing “rain checks.” But overall, AmTote’s computerized systems were installed in thousands of racetracks worldwide, indicating it had a pretty good track record.

Could Computers Help You Beat the Spread?

For the next segment, Robert Archer and Michael Orkin joined Cheifet and Morrow back in the San Mateo studio. Archer was president of PDS Sports. Orkin was co-founder of Best Bet Software and a professor of statistics at California State University, Hayward (now California State University, East Bay).

Morrow noted that Roxy Roxborough, the guest from the previous segment, was a skilled oddsmaker and seemed to have an edge by looking at the data but not necessarily using computers to do analysis. Did Orkin have any comment? Orkin said that if Roxborough picked the lines and there was a bias in it, the betters would pick up on it and start betting accordingly. This would lock the bookmakers into a system where they would lose.

Following up, Morrow asked if Roxborough could use a computer program to keep track of that. Orkin said Roxborough likely used computers to keep up with data. But if he actually used a program to pick the line he’d have to keep modifying it if there were any biases that occurred. Oddsmaking was a dynamic process. So to get locked into a program would not be helpful.

Turning to Archer, Cheifet asked if oddsmaking could actually be reduced to statistics. Archer said no, it would always be subjective. The computer was an instrument where the user could manipulate all the data to where they wanted it and help them make a decision. Cheifet asked for a demonstration of this using Archer’s product, Thoroughbred Handicapping System (THS). Archer said the program required the user to enter data from the Daily Racing Form for a particular race. There were 3 variables for the race itself and 11 variables for the horse. Some of the variables included the horse’s number of races started, number of wins, total earnings, and days away from the racetrack.

For the demonstration, Cheifet said they’d entered data for three different horses. THS then produced a “power rating” for each horse. The horse with the highest power rating was considered the “favorite” to win the race. Archer said you were looking for a 3.5-point spread between the first and second horses in order to have a “playable race,” subject to the handicapper’s personal bias. Cheifet asked how THS actually calculated the power ratings. Archer said the program compared the inputted data to a predetermined set of standards.

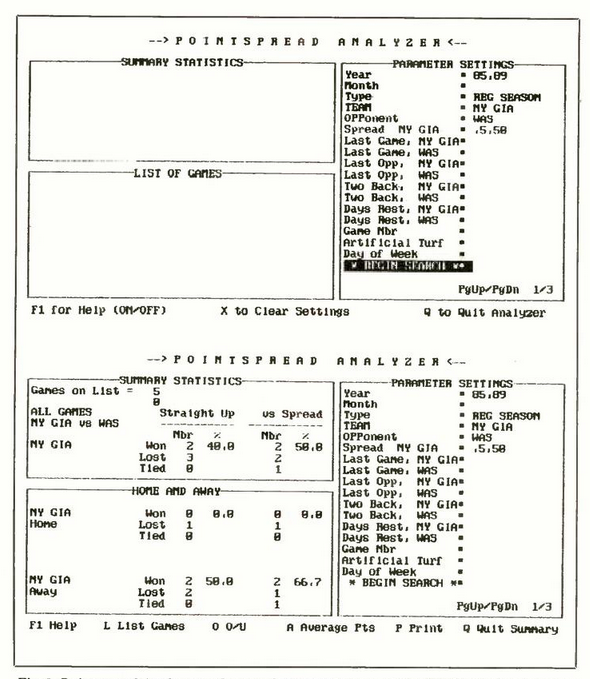

Cheifet then asked Orkin about his program, Pointspread Analyzer, which targeted people betting on American football. Orkin said Analyzer contained data about every National Football League game played since 1979. It was a self-contained database on a single floppy disk. The user could query the database to learn about a team’s performance in various situations.

Cheifet asked for a demonstration. Orkin pulled up the program’s main screen, which included a number of “parameter settings.” Orkin said he asked for the New York Giants record against the pointspread between 1983 and 1986 after losing a road game the previous week. According to the search results, the Giants were 10-5 (66.7 percent) against the spread in the subsequent game. You could also retrieve a list of specific games meeting the search criteria.

At Cheifet’s request, Orkin then ran a search of all Monday Night Football games played since 1983. According to Analyzer, the home team won against the spread 59.4 percent of the time. Morrow asked if this was something that a bettor considered important. Orkin said it was when deciding what team to pick.

Cheifet asked Orkin how much of an advantage a program like Analyzer actually provided. Orkin said the software enabled the bettor to answer a question in a couple of seconds that might take a few hours to do by hand, or that they might not be able to answer at all.

Computers Helped Keep Pennsylvania Lottery Safe

For the final segment, Cheifet presented a remote report on the Pennsylvania Lottery. He noted that each year, Pennsylvania sold more than $1 billion in lottery tickets. And when the jackpot got big enough, that could mean a sales volume of up to one million sales transactions per hour.

None of this would be possible without computers, Cheifet said. And indeed the Pennsylvania Lottery had a massive investment in computers. Retailers sold lottery numbers from online terminals. Computers recreated each day’s games on a separate IBM backup system to ensure the integrity of the games. Computers were also used to analyze sales, project jackpots, and to monitor the actual betting.

In fact, Cheifet said, the Pennsylvania Lottery ran one of the most complex computer networks, with nearly 3,000 terminals on a Control Data Corporation system that had 100 percent redundancy and a “hot” backup–so one rarely heard that the computer was down. Michael Keyser, the Pennsylvania Lottery’s online supervisor, told Cheifet that in ten years the system’s uptime was 99.98 percent, as close to perfection as possible with an online system. Keyser said he couldn’t recall any major downtime since the system came online in 1977.

Cheifet noted that one of the primary functions of the computer system was to constantly monitor the lottery’s payoff liability to make sure that no one could “break the bank.” For the lottery’s “Big Four” game, which paid odds of 5000-1, the computer made sure that the state was never exposed to a liability in excess of $5 million per game. If the system detected heavy betting on a particular number, such as “1111,” it sent out a warning and cut off betting on that number.

Heavy betting on a specific number often occurred because lottery players tended to follow certain common patterns. For example, Michael Keyser said that when Pete Rose played for the Philadelphia Phillies and reached a certain number of career hits, many bettors would play that number. Other numbers that might be heavily bet included the Super Bowl score, the Chinese New Year, and the Jewish New Year.

Cheifet said that while the computer system assured a random drawing every time, the law of averages took awhile to work. Keyser said there had been over 3,100 daily number drawings (pick three) in 10 years. But there were two or three dozen numbers out of 1,000 that had still never come up.

The lottery had many safeguards to protect against being broken into, Cheifet said. The computer shut down all games exactly 168 seconds prior to the winning drawing so that all tapes could be removed and nobody could enter a winning number after the drawing. And computer experts actually hired hackers to try and break into the system in order to identify potential weaknesses.

Seven years earlier, Cheifet noted, the Pennsylvania Lottery did fall victim to a scandal, but it had nothing to do with the computers. Rather, most of the balls used in the drawing were weighted so that only 6s would rise to the top. A slow-motion analysis of the drawing–combined with computer analysis–helped identify the culprits. Keyser said offline processing showed exactly where certain bets were coming from and retailers were able to identify the purchasers.

But despite all the computers, Cheifet said, when it came to calculating the payoffs, no one trusted the machines. The numbers were still calculated manually with a calculator, some paper, and a pencil. Keyser added that when you’re sitting alone giving away millions of dollars, you had to be absolutely sure you were doing it perfectly.

Even More PC Clones Unveiled at Spring COMDEX

Susan Chase presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in March 1987.

- NCR Corporation unveiled two new AT-compatible PCs: a 286 and a 386 machine based on NCR’s incremental workstation architecture. Chase said the new workstations would be available later in 1987.

- Hewlett-Packard planned to release three new technical computers and said that its previously announced 930 and 950 business computers would finally ship in fall 1987. Chase noted that all five computers were based on the RISC architecture.

- Digital Equipment Corporation and Cray Research said they would soon introduce a new interface between their computers. Chase said it would be a combination of DEC’s hardware and Cray’s software and represented an effort to speed up data-transfer rates and step up pressure on IBM in the scientific computing market.

- Paul Schindler reviewed KidsTime (Great Wave Software, $50), a collection of five educational software programs for the Macintosh.

- At the spring COMDEX show in Atlanta, Sharp announced plans to introduce two portables: a PC-AT clone called the PC-7200, and the XT-compatible PC-4500. Chase said that Samsung also planned to show off its new PC clones at COMDEX.

- Japanese companies were working on a new method of software distribution designed to eliminate software piracy. Chase said the proposed “Software Service System” was a box that could be attached to existing computers or built into new machines. Software would not run on the computer until the box authorized it. Users would have to purchase a card to activate the box and give credit for any software purchased.

Keyser’s Computer Played Key Role in Foiling 1980 Lottery Scandal

So let’s start with that earlier Pennsylvania Lottery scandal that Stewart Cheifet alluded to in his closing report. It’s true that unlike the 1988 scandal, the 1980 affair had nothing to do directly with the lottery’s computer systems. But our guest from this episode, Michael Keyser, did unknowingly play a role in the affair.

The mastermind of the scheme turned out to be a well-known local broadcaster, Nick Perry, who was actually the host of the daily lottery drawing on WTAE-TV in Pittsburgh. Sometime around February 1980, Perry started working on a plan to rig the daily number game by replacing the normal balls used in the drawing with weighted balls, as Cheifet described.

According to court records, Perry obtained a set of scales from Jack Maragos, who co-owned a vending machine business with his brother and Perry. Perry then gave the scales and a hypodermic needle to Joseph Bock, a stagehand at WTAE-TV. Bock prepared the doctored balls by injecting them with white latex paint. Another stagehand, Fred Luman, then swapped the weighted balls for the real ones just before the April 24, 1980, drawing.

At the time, the Pennsylvania Lottery had a senior citizen from the community conduct the actual drawing. The senior selected for the April 24 drawing was scheduled to participate in a practice run at 6:30 p.m. that evening. Edward Plevel, a district manager for the Pennsylvania Lottery, was supposed to supervise this process. But Plevel was also in on Perry’s scheme. He ended the practice early at 6 a.m. and then left the machines unattended for 45 minutes, giving Luman enough time to pull off the switcheroo.

To clarify, the scheme involved swapping out all of the lottery balls except those with the numbers 4 and 6. On April 24, the Margos brothers drove around Philadelphia and bought up hundreds of lottery tickets featuring various combinations of 4 and 6. As it turned out, the number actually drawn that evening was ‘666’. After the drawing, Plevel made the official report of the outcome to Michael Keyser, who was in charge of the daily number drawing. (To be clear, Keyser was not part of the scheme.)

The lottery ended up paying out $3.5 million in winning ‘666’ tickets. This immediately raised suspicions–at least with the local organized crime syndicate. Tony Grosso, who ran an illegal numbers racket that also took bets on the Pennsylvania lottery, was informed by his subordinates that someone was placing an unusually high number of wagers on 4 and 6 combinations for the April 24. That “someone” was the Maragos brothers, who apparently weren’t content to confine their betting to the state-approved lottery dealers.

Grosso immediately tipped off a local reporter that the April 24 drawing had been rigged–and not by him. Initially, Pennsylvania officials dismissed any suggestion the game had been tampered with. But soon other reports came in from Pennsylvania Lottery retailers. One retailer said they saw two men in a white Cadillac come in and purchase hundreds of lottery tickets with 4 and 6 combinations. Another witness, a newsstand operator, said Edward Plevel purchased $80 in lottery tickets that same day, again all in 4 and 6 combinations. Plevel later told the operator to lie and say a “woman bought the tickets and cashed them” if the police started asking questions.

In September 1980, a special grand jury recommended criminal charges against Perry, Plevel, Bock, Luman, and the Maragos brothers. There being little honor among thieves, the Maragos brothers agreed to testify in exchange for immunity. Bock and Luman negotiated plea agreements. Perry and Plevel were the only defendants who went to trial. A jury found both men guilty in May 1981. They each served two years in prison. Perry died in 2003.

Interestingly, the use of a computer played a critical role in Plevel and Perry’s unsuccessful appeals of their convictions to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Plevel and Perry were both tried in Dauphin County, which is where the state capital of Harrisburg is located. But the rigged lottery drawing took place in Allegheny County (Pittsburgh). Perry and Plevel therefore argued they were deprived of their Sixth Amendment right to a trial in the county where their alleged crime occurred.

The Supreme Court rejected that argument. In an August 1983 opinion, the Court noted that Michael Keyser programmed the final ‘666’ outcome into his computer in Harrisburg. Furthermore, every winning ticket purchased by the Maragos brothers and Plevel had to be validated by the lottery’s computers in Harrisburg. Thus, the fraudulent scheme conducted by Plevel and Perry involved numerous “essential” criminal acts that occurred in Dauphin County.

Data Broadcasting Engorged LVSC, Computer Sports World During Dot-com Bubble

Michael “Roxy” Roxborough is originally from Vancouver, British Columbia. While attending American University in Washington, DC, he started dabbling in illegal bookmaking. After graduating, he returned to Vancouver and continued his bookmaking activities in places ranging from pool halls to the Vancouver Stock Exchange.

In 1975, Roxborough decided to take his talents to Las Vegas, then the only place you could legally place single-game sports bets in North America. He founded Las Vegas Sports Consultants (LVSC) in 1983 after being approached by the Stardust Hotel and Casino to act as its oddsmaker. Roxborough went on to become one of the country’s best-known betting line experts.

Roxborough sold LVSC in 1995 to Data Broadcasting Corporation (DBC). I discussed the lengthy history of DBC in an earlier post. To briefly recap, DBC emerged from the bankruptcy of its parent company, Financial News Network, Inc., in 1992. During the 1990s DBC pursued an aggressive expansion strategy, particularly in the burgeoning dot-com economy. LVSC was a key part of a new division called DBC Sports, which later absorbed another company profiled in this episode, Computer Sports World (CSW).

CSW started out as a free online bulletin board back in 1976. Darryl Martin, the service’s founder, decided to convert it into an all-sports BBS in 1981. By 1984, he’d sold CSW to the San Francisco Chronicle’s parent company and the service expanded into offering full-service sports statistics.

And this was a premium service. According to an October 1987 column by Dan Gutman, the once free BBS now charged $175 for initial signup plus 43 cents per minute for access (63 cents during prime time hours!) Gutman noted that some subscribers were paying upwards of $630 per month to look at CSW’s data.

DBC acquired CSW in 1997. That same year, DBC joined with CBS to create MarketWatch.com, a financial news website. CBS was also a minority shareholder in SportsLine.com, a sports news website. After MarketWatch’s initial public offering in 1999 quickly went from boom to bust, DBC’s own stock collapsed. In 2000, SportsLine.com subsidiary Vegasinsider.com purchased DBC Sports, including Las Vegas Sports Consultants. But this created problems for CBS, which owned 31 percent of VegasInsider.com, as it held the television rights for the NCAA basketball tournament and wanted to create a new NCAA-sanctioned website at SportsLine.com. The NCAA objected to CBS owning a stake in a sports oddsmaker. So in 2003, SportsLine.com sold VegasInsider.com to Sports Information Ltd., a United Kingdom-based company.

In 2019, the Denmark-based Better Collective group acquired VegasInsider.com. It seems that the Las Vegas Sports Consultants and Computer Sports World brands were retired sometime before this latest acquisition.

As for Roxy Roxborough, he retired after selling LVSC and moved to Thailand, according to a 2015 ESPN profile by Dave Tuley. Robin Cobbey, the former CSW president who appeared in this episode, has worked as a market research consultant since the late 1980s.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was likely first broadcast around March 17, 1987. Based on the discussion of the DePaul-Georgia Tech men’s basketball game, the studio segments were probably recorded on February 21, 1987.

- For the record, DePaul won 84-67, which I’m guessing was enough to beat the spread. It was a banner year for the Chicago-based school, which posted a 28-3 record. Led by future NBA player Rod Strickland, DePaul advanced to the regional semifinals of the 1987 NCAA tournament.

- William S. Redd founded International Game Technology (IGT) in 1975. Italy-based GTECH S.p.A acquired IGT in July 2014 for $6.4 billion. GETECH then renamed itself International Game Technology PLC, which remains in business today.

- Charles Mathewson took over as CEO of the original IGT from William Redd in December 1986. He remained with the company until October 2003, when he retired as chairman of the company’s board. Matthewson died in November 2021 at the age of 93.

- Peter Dickinson remained with IGT as a senior executive until his sudden death in June 1994 due to a heart attack. He was 47.

- Bob Bittman retired from IGT in December 2008 after 23 years with the company.

- The Harrah’s casino in Reno closed in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and never reopened. An investment company subsequently purchased the property and announced plans to redevelop it into an apartment complex.

- I did not find much information about Robert Archer or his company, PDS Sports. PDS Sports was a subsidiary of a Utah-based company, Post Data Services Corporation, which existed from 1971 to 1988 according to state records. Archer registered Post Data Services as a foreign corporation in California in 1987 but there were no further filings after that time. I also found sporadic references to Thoroughbred Handicapping System marketed under the “Sports Judge’s” name. But I don’t know how long the program was on the market for or what ultimately became of Archer and his company.

- Michael Orkin earned his doctorate in statistics from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1971. He joined the faculty at Cal State, Hayward, in 1973 and remained with the school for 31 years, serving as chairman of the statistics department and later as an associate dean. In 2012, Orkin became vice chancellor for educational services for the Peralta Community College District in California. After leaving that position in 2017, he joined Berkeley City College, a part of the Peralta system, as a member of the mathematics faculty.

- It’s ironic that Michael Keyser mentioned Pete Rose’s hit total as a common source of daily lottery numbers. Rose was famously banned from Major League Baseball for life in August 1989 after a report commissioned by former Commissioner of Baseball Peter Ueberroth found evidence that Rose had bet on baseball games while serving as manager of the Cincinnati Reds. A few weeks before that report came out, Ueberroth backed out of a deal to sell MLB’s official statistics to Computer Sports World. Ueberroth was apparently shocked–shocked–to learn that people were using CSW stats as a means of gambling and not just to play rotisserie baseball.

- I’ll have more to say about the Mattel Horse Race Analyzer in a forthcoming special post.