Computer Chronicles Revisited 81 — The TRS-80 Model 102, NEC Multispeed, Zenith Z-181, Toshiba T3100, and the Dynamac

Unlike many people who cover computer history, I generally avoid talking about prices “adjusted for inflation” when discussing older products. For example, one of the products demonstrated in this next Computer Chronicles episode, the Zenith Z-181 portable computer, originally retailed for $2,399 in 1987. If you run that figure through an online inflation calculator, it will tell you that this is the equivalent of $5,395.60 in “purchasing power” in December 2022.

I see a couple of problems with talking about computer prices in these terms. First, a computer is not like a quart of milk or some other commodity that has remained relatively consistent in terms of quality over the years. The Z-181 had 640 KB or memory. The laptop I’m typing this post on right now–a roughly 10-year Dell Latitude E7240 that I paid about $250 for refurbished–has 8 GB. If you were to price both machines on a “per-kilobyte” basis, the old Dell is infinitely cheaper than the antique Zenith.

Second, stating the price of a computer in terms of relative purchasing power does not necessarily place it in the proper market context. On the surface, paying the 2022 equivalent of roughly $5,400 for a consumer laptop sounds ridiculous. Except that the Z-181 was not a consumer laptop. Indeed, most of the portable computers we’ll see in this episode were targeted at a market largely composed of big business and government customers. There was no “consumer laptop” market to speak of in 1987.

Put another way, nobody was buying the equivalent of a $200 Chromebook during this period. The closest modern equivalent of a Z-181 in terms of market positioning may be something like a MacBook Pro, where a 16-inch model can set you back around $2,399–or what a similarly situated customer would have paid for the Z-181 back in 1987.

Fully Functional Portables Swept Away the Old Remnants

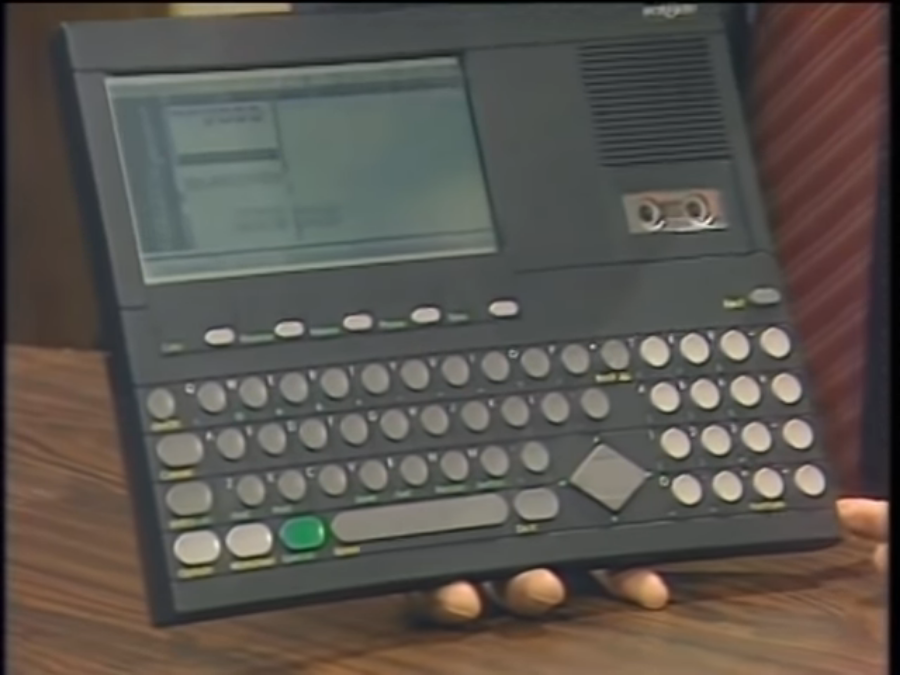

Stewart Cheifet opened this episode with his customary show-and-tell, holding a Convergent Technologies Workslate (see below), an early portable computer. Cheifet noted the machine came about four years ago and was already considered an antique. It was the “old remnant” of what laptops used to be, i.e., a machine with a small, hard-to-read display.

Cheifet said that while laptops once struggled to make a dent in the market, today everybody was trying to buy them, leading to shortages in some places. What had changed? Kildall said the key was that laptops now had “full functionality.” People were spoiled by using modern AT-compatibles with a nice keyboard in their offices. Now you could buy a portable with a good, readable display and a hard disk system. This made it possible to use a laptop in a situation like an airplane ride.

Portables as “Genuine Alternatives” for Business Travelers

Wendy Woods presented her first report, which she narrated over some B-roll footage of a Chevron Company traveling salesman, Joe Dennison, going about his work. Woods said that taking a computer on the road was not for everyone. But many business travelers like Dennison were discovering the practical side to carrying a portable machine.

Dennison sold fertilizer chemicals for Chevron throughout central California, Woods explained. He’d been carrying a Hewlett-Packard Portable 110 for over two years. At his hotel, he could prepare sales reports and keep track of his appointments. Through a modem connection, he could get account information from his office’s mainframe.

Woods said that Dennison spent several days at a time in rural areas, but his office traveled with him, so long as he could find an outlet and a telephone. He even took his HP Portable to visit clients on sales calls. This was no more cumbersome than carrying a case full of binders–and the computer could hold far more information.

The HP Portable came with software built into a ROM chip. But Dennison also carried a disk drive and a printer to make hard copies of documents. If he was unable to answer a customer’s question, he could call up Chevron’s database and retrieve up-to-the-minute pricing and stock (inventory) information.

One of the most common problems faced by business travelers, Woods said, was communicating with other co-workers, who may themselves be on the road or simply hard to reach. The solution to that problem was electronic mail, a common mailbox where Dennison could receive and transmit messages when convenient.

Woods added that portable computers had yet to achieve the popularity originally predicted by industry analysts. But with legible screens, lighter weight, and some serious software, portables were now becoming genuine alternatives.

NEC Offered Two Speeds with a Supertwist

Bob Wade and James D. Bartlett joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first studio round table. Wade was a marketing manager with Tandy/Radio Shack. Bartlett was a marketing manager with NEC Home Electronics.

Wade was there to discuss the TRS-80 Model 102 (see below), the most recent update to the Model 100 line of portable computers. Kildall noted that Tandy had sold about 250,000 machines in the 100 line over the past six years, so Wade probably had a good idea of their customer profile. Wade said the largest group of Model 100/102 users were professional journalists. Virtually all major newspapers in the United States and around the world used the Model 102 for remote data transmission back to the home offices for publication.

Kildall asked if that was how the machine was originally conceived. Wade said the original thought on the 100 line was to build a machine that could be used to retrieve data in the field and then transmit it back to the home office.

Cheifet said the main features of the Model 100 were that it was very light and portable. He added that Tandy now also offered a cellular telephone option with the machine. Taking his cue, Wade pulled out a giant cellular telephone from under the desk (see below), which explained could be connected to the 102. He said police departments throughout the United States were now experimenting using this setup to transmit data from the field to their local station’s database.

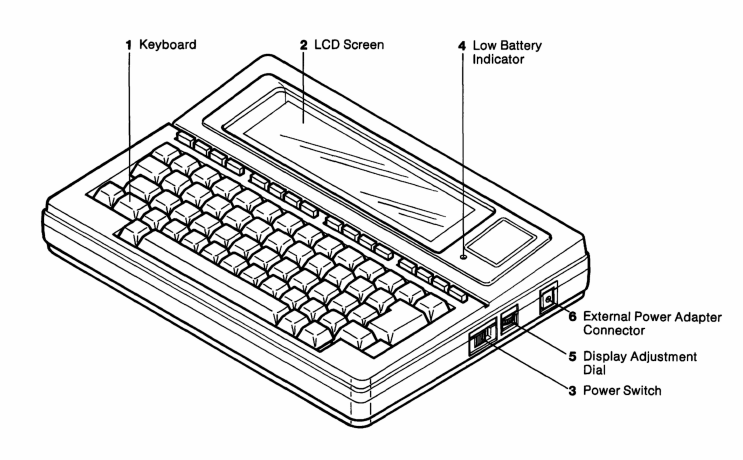

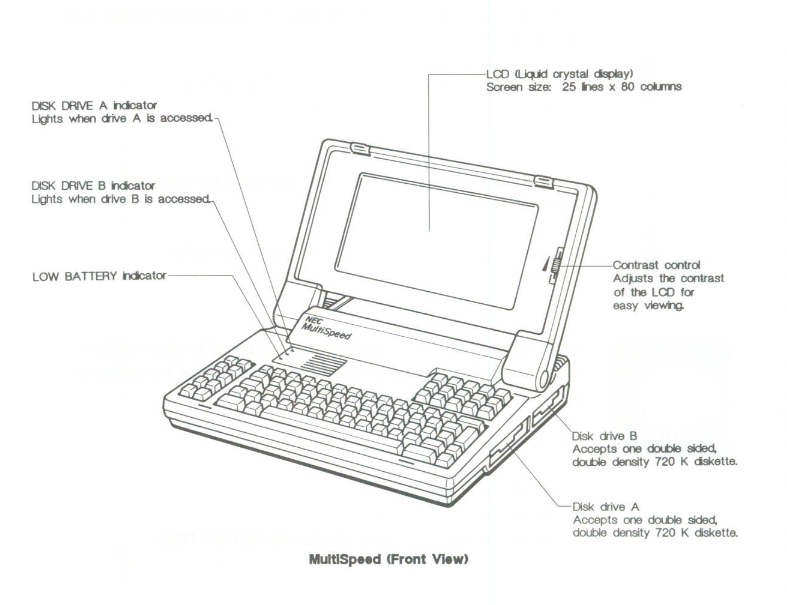

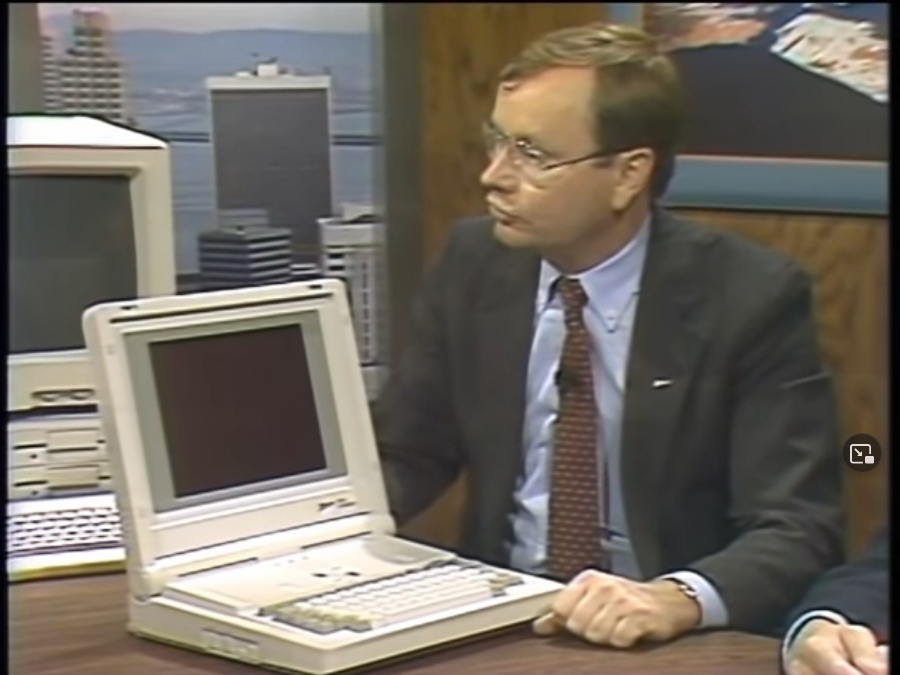

Cheifet turned to Bartlett and asked about his company’s product, the NEC Multispeed (see below). Bartlett said the Multispeed was an MS-DOS machine that was IBM PC compatible. NEC developed the Multispeed based on market research that showed people in the business world wanted an “expansion” or “supplement” to add to their desktop machine. NEC expected there would be a transition in the near future from desktops to portable machines that could provide a “no compromise” solution, i.e., a computer that performed as well as a desktop but that could be taken on the road.

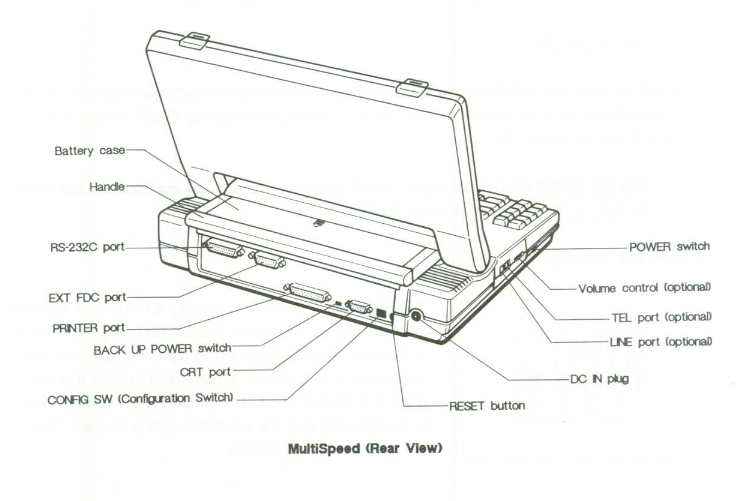

Bartlett went on to explain that the Multispeed’s display was a “supertwist” LCD, which he claimed was the “highest readability” technology on the market. The display was also detachable, so the user could still easily connect a color monitor behind the machine via an RGB port. The Multispeed also had a full-sized keyboard with a separate numeric keypad and function keys on the left side (similar to the Model F layout used on the IBM PC-AT keyboard). On the left side of the Multispeed was a connection for an optional 300- or 1200-baud Hayes-compatible modem. On the back there was a serial port, parallel port, RGB video port, external disk drive controller port, and various configuration switches.

Kildall pointed out the one thing that seemed to be missing from the Multispeed was a hard disk. He said that for a user like himself, it would be nice to have a 10 MB or 20 MB hard drive. Bartlett said the Multispeed came with two 720 KB floppy disk drives. NEC had thought about adding a 20 MB hard disk, but their market research indicated that portability and some degree of battery life–approximately 4 to 6 hours–was considered more important. To accomplish that with the Multispeed, a 16-bit machine running at either 4.77 or 9.54 MHz, meant that adding a hard disk would have effectively required the user to be 6 feet from an AC outlet and plugged in all the time.

Cheifet asked about the software included with the Multispeed. He noted that much like the TRS-80 Model 102, there was built-in software contained on ROM chips. There were also the previously mentioned floppy drives. How did that work in terms of carrying around software? Bartlett pulled off a cover on the bottom of the Multispeed, which showed the built-in ROM software chips. The ROM contained 512 KB of software including a notepad, filer, telephone dialer, and other productivity tools. Cheifet asked if you could use more “traditional” software like Lotus 1-2-3. Bartlett said you could buy such software on floppy disk and use it with the Multispeed. But he said third parties could also develop specialized applications for use with the ROM sockets, which could provide a “turnkey solution” for certain cases.

Cheifet asked about the price of the Multispeed. Bartlett said the suggested retail price was $1,995. Cheifet then asked about the “multispeed” nature of the machine–i.e., why did it need to run at both 4.77 and 9.54 MHz? Bartlett said most software was capable of running just fine at 4.77 MHz but some programs benefited from the higher 9.54 MHz speed. (For reference, the original IBM Personal Computer ran at 4.77 MHz.) By allowing the user to choose between the speeds, they could opt for the lower 4.77 MHz to help save on battery power.

To Backlight or Not to Backlight?

Andrew Czernek and Thomas Sherrard joined Cheifet and Kildall for the next segment. Czernek was a marketing director with Zenith Data Systems. Sherrard was a product marketing manager with Toshiba America.

Kildall opened by noting an early criticism of portable computers were the displays, which were difficult to read in poor lighting conditions, such as while sitting in an airplane. He asked Czernek what’s changed in terms of display technology. Czernek said Zenith’s own research confirmed that people had troubles even knowing whether or not the display was on with some older portable computers. Two things had changed with respect to Zenith’s new portable computer, the Z-181. First, one of Zenith’s engineers realized a few years ago that while an LCD may not be acceptable, you could put a light behind it and still have the machine work off of batteries. Second, LCD technology had advanced so that the screen could be readable from a side view, not just while looking directly at it.

Cheifet asked for a further explanation of the “supertwist” LCD technology mentioned in the prior segment. Czernek said supertwist was a technology that twists the crystals far enough so you could see them from the side as opposed to viewing the display within 10 degrees from center. Kildall asked about the backlighting and whether it was an important part of the technology. Czernek said he thought it was “mandatory.”

Kildall asked if these new LCD screen portables were also using the CGA graphics standard. Czernek said the Z-181 used CGA but LCDs displayed information differently–specifically in blocks–so you didn’t have spots appearing on the screen as you did with high-resolution monitors.

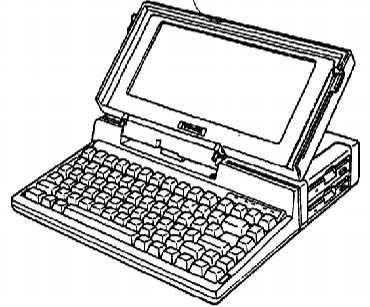

Cheifet asked Czernek for a “tour” of the Z-181 (see below). Czernek explained the machine had a cover that folded down and completely covered the keyboard. There was a full-size illuminated screen. There were two 3.5-inch floppy disk drives that “popped up” in the front from underneath the screen. On the side was a port to add a modem. On the back there was a serial port, parallel port, video connector, and an external floppy disk drive adapter. The Z-181 also came with 640 KB of RAM. Cheifet asked about the price. Czernek said the suggested retail price was $2,399.

Cheifet then turned to Sherrard and asked about one of his company’s portables, the Toshiba T1100 Plus (see below). What was new and distinctive about this machine? Sherrard said the most important thing in a portable was portability, which meant minimizing size and weight. The T1100 Plus was just under 10 pounds (~4.5 kg) and about 1-foot square. This made it reasonable to carry.

Cheifet asked about Toshiba’s approach to the screen. Sherrard said it was also a supertwist LCD. It wasn’t backlit like the Z-181 but rather relied on a reflective technology. (If you’ve ever played an original Nintendo Game Boy, it’s that type of screen, albeit larger.) Sherrard conceded this meant you only got a good display when there was bright light.

Cheifet asked about the battery life on the T1100 Plus. Sherrard said the battery could run for about 8 hours. But if you used the disk drives or modem heavily you would obviously get less battery life. But he said for normal use, the battery would last a cross-country airplane flight or all day in an office environment.

Cheifet noted that both the Z-181 and the T1100 Plus used 3.5-inch microfloppy drives, which was now becoming the standard. But it was still a pain in the neck to get software, most of which was still sold on 5.25-inch floppy disks. Did either Czernek or Sherrard see that as a problem? Czernek said that by the end of 1987, he expected all software would be available in the 3.5-inch format. He said Zenith did a check back in June 1986 and found there were 75 major software packages available on 3.5-inch disks. Today that number was around 250 packages. So eventually the 3.5-inch disks would replace the 5.25-inch disks as they were cheaper, used less energy, and offered more design flexibility for hardware manufacturers in developing lighter portable machines.

Kildall asked if these types of portable computers might eventually replace the desktop machines. Czerkek said he was skeptical that would happen anytime soon, as desktop machines were much more flexible. For example, they had expansion slots and much higher display resolutions, as well as color. The desktop machines also had faster processors like the Intel 80386 and hard disk drives as large as 120 MB. As fast as portables moved up, desktops would move up and continue to outpace them.

Cheifet asked about the time to recharge a dead battery. Sherrard said it took about 6 hours to recharge the T1100 Plus using an AC adapter, and you could still use the machine during that time. Of course, it would charge more quickly if the machine was not in use. Czernek said the Z-181 had replaceable battery packs as an option. You could also purchase a high-speed charger that cut the battery charge time from 6 to 8 hours down to 3 to 4 hours.

GRiD Powered Nascent GPS Market

Wendy Woods presented her second remote report, which focused on the use of the GRiD portable computer. Woods said that whether flying in the sky, at sea, or on ground, portables like the GRiD were being used to accurately and quickly locate a geographical point on Earth.

Over some B-roll footage, Woods explained that Trimble Navigation manufactured an Earth station receiver and antenna that gathered data from satellites and fed it into a GRiD equipped with Trimble’s software and recorded on floppy disk. The data was accurate up to 4 feet from anywhere on the globe.

Paul Perrault, a product marketing manager with Trimble Navigation, told Woods that the advantage of using a laptop computer was that the surveyor was able to take the data and process it in the field, so they know before going home whether the data was good. That was important to the surveying community because it was often very expensive to hire an entire crew.

Woods said that Trimble was the largest seller of computerized survey equipment. It had sold over 200 of their $40,000 GPS units and virtually all of their customers used them with GRiD. Altogether, GRiD said its machines were in use by more than 50 United States federal government agencies and more than 400 Fortune 1000 companies. And as portables became lighter and more powerful–like the new GRiD Lite–even more innovative applications for them would be found.

The First Portable Macintosh–and It Wasn’t From Apple

Britt Blaser joined Cheifet, Kildall, and Toshiba’s Thomas Sherrard for the final segment. Blaser was a vice president at Dynamac Computer Products.

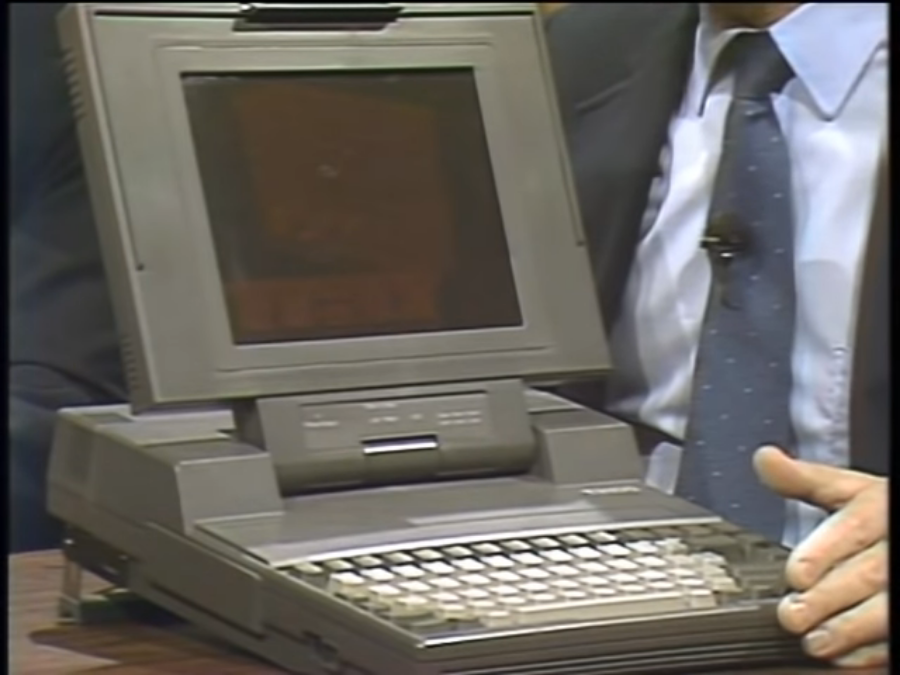

Kildall asked Sherrard about another new Toshiba portable, the T3100. This was a portable machine designed to run on AC power; there was no battery. Kildall wanted to know who was buying this type of machine. Sherrard said all kinds of people, including accountants, auditors, and consultants who needed to carry their machines to work. They had previously been lugging machines like the Compaq Portable, or they were keeping separate machines at home and at work. The T3100 allowed them to use a single machine as it could do almost anything that a PC-AT could do but in a portable package.

Kildall asked for more information about the T3100. Sherrard explained it was an AT-compatible with an Intel 80286 processor. It had a gas plasma display with a 640-by-400 resolution, which was double that of a typical CGA monitor. Much to Kildall’s pleasure, the T3100 also came with a built-in 10 MB hard disk drive in addition to a 720 KB, 3.5-inch floppy disk drive. The portable could also be connected to a separate chassis to accept IBM-compatible expansion cards.

Cheifet asked why Toshiba went with a gas plasma display for the T3100. Sherrard said it had a lot of desirable characteristics. The display was “very, very readable” and “extremely sharp.” The display made it possible to use applications that required high-resolution graphics such as desktop publishing. The display also put out light, which made it easier to read than an LCD. And since the machine didn’t run off of batteries, conserving power wasn’t a problem.

Cheifet noted that hard disks were fragile and asked if a user should be concerned about using a portable with a built-in hard drive. Sherrard said that shouldn’t be a concern, as the T3100’s hard disk was engineered specifically for portable applications. It was intended to take some “hard knocks.”

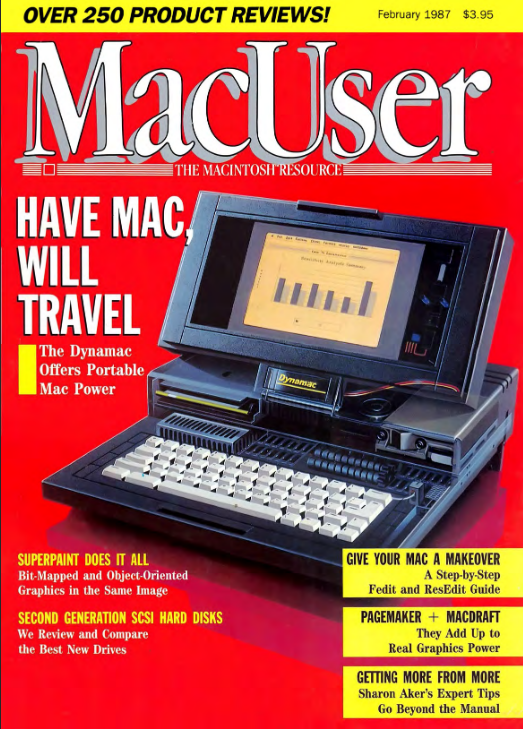

Cheifet noted the T3100 was the first portable AT machine. He then turned to Blaser, who was offering the first portable Macintosh, the Dynamac (see below). Blaser said the Dynamac took the same philosophy as the T3100. He said customers were responding in particular to the Dynamac’s built-in 40 MB hard drive. (The original Macintosh did not come with a hard drive, although there were third-party modifications available.) Blaser claimed the Dynamac could take up to 75g of force when it wasn’t operating and 10g when it was not. The Dynamac also came with 4 MB of memory and a built-in modem. On the demo unit, Blaser showed there were eight active applications–including Microsoft Excel and MacDraw–loaded into just 2.9 MB of RAM.

Cheifet asked if there were any compromises made in making the Mac portable. Blaser said no. In fact, the Dynamac extended the Macintosh’s capabilities. Blaser then showed that the back of the Dynamac contained the same ports as a regular Macintosh, since it used the same motherboard.

Cheifet asked if there were any compromises made in making the Mac portable. Blaser said no. In fact, the Dynamac extended the Macintosh’s capabilities. Blaser then showed that the back of the Dynamac contained the same ports as a regular Macintosh, since it used the same motherboard.

Cheifet asked about the audience for the Dynamac given the machine was portable but, like the Toshiba T3100, only ran on AC power and not a battery. Blaser said one target customer would be a journalist who might not want to record things on-site but would use a Dynamac to edit copy downloaded from a TRS-80 Model 102. Other potential customers included field workers and auditors. Again, Blaser emphasized the value of the built-in 40 MB hard drive. And the Dynamac could also be configured to work with an external keyboard, keypad, and monitor. Cheifet asked if the Dynamac would be useful for desktop publishing. Blaser said absolutely. He added that the production version of the Dynamac–as opposed to the demo unit he had in the studio–would have an electroluminescent display with the same 640-by-400 resolution as the T3100.

Reiterating a question from the prior segment, Kildall asked Blaser for his view on portables possibly replacing desktop machines. Blaser said that was the idea behind the Dynamac–to have a “jerk-and-run machine” that you could unplug and take with you. The hard disk made that possible. He added there was also an external adapter available to run the Dynamac on a battery.

Cheifet asked about what we could expect in the development of laptops over the next couple of years. Sherrard said he expected more of the same–i.e., more disk storage, more speed, more memory, and lighter weight for the same kind of capabilities. Blaser added there would be further innovation with respect to non-volatile RAM and battery life.

Would the New Amiga be MS-DOS Compatible?

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in February 1987.

- There were rumors that the new Amiga 2000 would be capable of running MS-DOS software through an add-on board called the Amiga Bridge. Cheifet added the new Amiga would use a Motorola 68000 microprocessor coupled with a 68020 math coprocessor operating at 14 MHz. The base unit would sell for $1,500. Commodore was also expected to release a low-cost version of the original Amiga 1000 for around $600.

- Hewlett-Packard announced two new versions of its LaserJet printer: The LaserJet Series II Plus, a less-expensive version of the LaserJet Plus for around $3,000; and the high-end LaserJet 2000. Cheifet said analysts predicted laser printer sales overall would double in 1987 to more than $1 billion.

- The U.S. Coast Guard Academy became the 18th American college to require freshmen to buy personal computers, joining the ranks of the other U.S. military service academies. Cheifet said the Coast Guard Academy picked the Macintosh as its required computer.

- Ricks College in Idaho and Brigham Young University in Utah were the first schools to implement online class registration systems. Cheifet noted that even if students didn’t have a computer, they could still access the system via touch-tone phone.

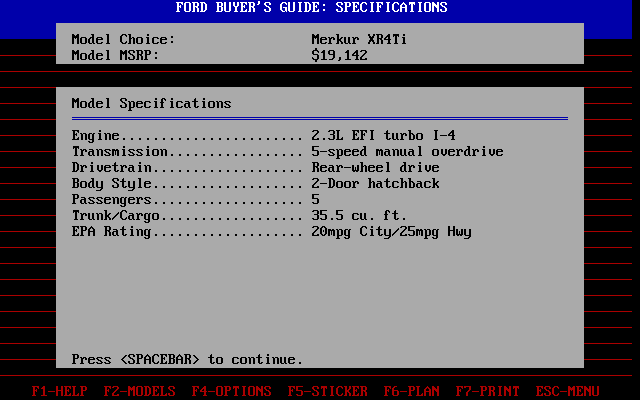

- Paul Schindler reviewed The Ford Simulator (Beck-Tech, Free), an advertisement for the Ford Merkur XR4Ti distributed on floppy disk.

- BusinessWeek magazine recently released Mutual Fund Scoreboard, a $49.95 floppy disk program that helped users select between 550 mutual funds.

- Another new program, Appetite for Business, offered a database of good restaurants in major American cities. Cheifet said the database would also be available as an online service beginning in June 1987.

- A Boston telephone company created an “online telephone pub” that charged users 10 cents per minute to participate in multi-user telephone conversations.

- A Chicago lawyer proposed creating an online law practice.

The Saga of Zenith Data Systems

Zenith Data Systems (ZDS) is a company we’ve seen before on Computer Chronicles. Prior to this episode, ZDS president Bob Dilworth–formerly of Morrow Designs–joined Cheifet and Kildall to discuss the Zenith Z-386 desktop PC at the end of 1986. Of course, Zenith’s Z-171 portable computer was based on the Morrow Pivot II, a design that ZDS had initially licensed and later acquired after Morrow Designs went bankrupt in 1986.

As far as I know, the Z-181 demonstrated in this episode had nothing to do with Morrow’s Z-171 design. One key difference between the two machines was that the 171 still used a 5.25-inch floppy disk drive while the 181 featured the signature “pop up” dual 3.25-inch drives.

From Airplane Kits to Home Electronics Kits

But let’s turn to the history of Zenith Data Systems itself. The company actually has its roots in two companies that were separately founded in Chicago. The first was Chicago Radio Labs. Founded by Ralph Matthews and Karl Hassel in 1918, Chicago Radio Labs initially marketed amateur radio equipment. In 1923, the business was renamed Zenith Radio Company and started selling “portable” radios–i.e., pre-assembled radios that could be physically moved, much like the portable computers in this episode. Zenith later transitioned into the television and broader consumer electronics business.

The second company was the Heath Company, which was started by Edward B. Heath in 1909. Originally known as the E.B. Heath Aerial Vehicle Company, Heath started out by manufacturing and selling aircraft parts to individuals who were building their own planes. In 1926, Heath and Claire Lindstedt developed the Parsol, a “single seat, high-wing monoplane with a low-cost, 23-horsepower Henderson motorcycle engine,” according to The Museum of Flight. Customers could purchase the plane fully constructed and ready-to-go for $975. Alternatively, they could buy a “kit” with the blueprints and unassembled parts for $199. Heath Co. ended up selling far more of the kits, about 1,000 in all.

Edward Heath himself died in February 1931. He was solo testing a new plane design–the Heath B-4–when one of the wing struts collapsed and he crashed into a farm just outside of Morton Grove, Illinois. The farmer witnessed the accident and pulled Heath’s body from the wreckage.

Heath’s mother inherited the E.B. Heath Aerial Vehicle Company after her son’s death. She sold the business to two brothers, John and Walter Clinnin, in May 1931. The Clinnins then relocated the company from Chicago to Niles, Michigan, and changed its name to the International Aircraft Corporation (IAC).

IAC didn’t last long. The Clinnin brothers filed for bankruptcy in 1934. Howard E. Anthony then purchased IAC’s assets at auction for $300. Anthony was an amateur aviator himself, having previously built one of Edward Heath’s Parasol plane kits back in the 1920s. Shortly after buying the company, Anthony married John Clinnin’s secretary, Helen Ballard, and the newlyweds rebuilt the business, which they renamed Heath Aircraft Company.

It was towards the end of World War II that Heath entered what became its most famous business–selling electronics kits. Heath initially bought up surplus electronic components left over from the war and repackaged them into what became known as “Heathkits.” The first Heathkits included parts to build an oscilloscope, which were later followed by amateur radio kits.

Sadly, Howard Anthony’s tenure with his newly successful company ended abruptly in July 1954. Like Edward Heath, Anthony died in a plane crash. Anthony and five others were killed when their twin-engine De Havilland Dove plane crashed into a mountain outside of Dayton, Tennessee.

Following her husband’s death, Helen Anthony sold Heath Co. to New Jersey-based Daystrom, Inc., for $1.85 million in February 1955. Daystrom was a budding industrial conglomerate that was primarily interested in Heath’s electronics business. Now a Daystrom subsidiary, Heath built a new headquarters and plant in St. Joseph, Michigan, in 1957 at a cost of around $2 million.

Adding an additional layer of corporate bureaucracy, Schlumberger Limited, a Houston-based oil and gas services company, acquired Daystrom in a stock swap in January 1962. Schlumberger had no interest in Heath or the electronics kit business. Rather, Schlumberger wanted to get its hands on another Daystrom subsidiary, Weston Electrical Instrument Corporation, which made instruments that were used in the oil and gas business. But Heath was profitable, so Schlumberger basically left it alone.

Zenith Turned Heathkits Into PCs for Government Buyers

Fast forward to 1977, and Heath Co. decided to extend its electronics kit business into the growing field of microcomputers. Starting in June 1977, Heath Co. sold a $375 small computer kit targeting hobbyists, and an assembled $1,195 computer targeting the business market.

Heath’s success with the Heathkit computers drew the attention of Zenith Radio Corporation. By this time, Zenith’s main business was manufacturing and selling television sets. But the American television industry was struggling against competition from Japanese manufacturers. Zenith management therefore decided that they needed to diversify and microcomputers would be a good area for expansion.

As it turned out, Schlumberger was in the process of acquiring Fairchild Semiconductor in 1979. This apparently prompted some antitrust concerns given that Fairchild was also in the consumer electronics business–they produced the Channel F, an early video game console, among other things–so in July 1979, Schulmberger sold Heath to Zenith Radio Corporation for $64.5 million in cash. That October, Zenith created a new subsidiary known as Zenith Data Systems, which took over the manufacturing of assembled microcomputer products. The original Heath Co. would continue to sell its Heathkits. Zenith also created Veritechnology to serve as its retail arm. ZDS, Heath, and Veritechnology were collectively known as the Zenith Computer Group.

By the time ZDS introduced the Z-181 in June 1986, the company was a leading seller of personal computers, albeit not at the consumer level. ZDS machines were mostly sold to government and business customers. As I detailed in my prior post on Morrow Designs, the Z-171 famously won ZDS a major contract with the Internal Revenue Service, beating out the IBM PC Convertible among other bids. The Z-181, in turn, was prompted by ZDS management’s concern that the Convertible could still pose a substantial competitive threat to other potential contracts.

Of course, ZDS was also concerned by its Japanese competition, including Toshiba’s T1100 Plus and T3100 portables. This led to a political showdown in 1987 that began not longer after the companies’ sales representatives appeared together on Chronicles. In March 1987, U.S. President Ronald Reagan imposed 100 percent tariffs on various Japanese exports, including laptop computers. This was prompted by a longstanding belief by the Reagan administration and congressional leaders that Japanese semiconductor companies had unfairly “dumped” inexpensive computer chips into the United States market to undercut domestic manufacturers.

Naturally, ZDS was thrilled with the tariffs. The parent company, which had changed its name from Zenith Radio Company to Zenith Electronics Corporation in 1984, had spent over a decade pursuing an unsuccessful antitrust lawsuit against a number of Japanese television manufacturers, including Toshiba, accusing them of colluding with Japan’s government to destroy to the U.S. domestic television production market.

On a practical level, the tariffs made Toshiba’s laptops politically and financially untenable when it came to U.S. government contracts. In August 1987, ZDS beat out Toshiba for a 90,000-laptop contract with the U.S. Air Force valued at around $105 million. (The contract was for the Z-184, which was similar to the 181 but did not have the pop-up disk drives.) Toshiba lost out not just because of the tariffs, but also because of a scandal involving one of the company’s subsidiaries allegedly selling submarine technology to the Soviet Union.

It should be noted here that while anti-Japanese bigotry helped fuel ZDS’ success in this time period, many of Zenith’s laptops were also manufactured in Japan. According to NewsBytes, most of the 90,000 computers used to fill that Air Force order were actually manufactured by Osaka-based Sanyo Corporation under an OEM license from ZDS. Zenith officials said they did their manufacturing in Japan largely because that’s where the good laptop screens were made.

ZDS Disappeared in 1990s PC Consolidation Wave

Zenith Data Systems continued to enjoy success well into the late 1980s. Indeed, from the parent company’s standpoint the computers were doing far better than the television sets. Eventually, Zenith Electronics Corporation management decided it needed to double down on its core business and raise capital to invest in new television technology. Accordingly, in December 1989 Zenith sold the entire Zenith Computer Group, which included ZDS and the original Heath Co., to Groupe Bull for $495.4 million in cash.

Groupe Bull is a French computer company whose own history dates back to 1931. Bull had passed through a number of owners–including General Electric and Honeywell–before it was nationalized by the French government in 1982. Zenith Data Systems continued to produce computers under its own name even after the Bull acquisition.

But Groupe Bull had its own financial struggles. In October 1993, the French government invested an additional $1.2 billion in the company. The previous year, French Prime Minister Edith Cresson negotiated a deal where IBM purchased a 5.7 percent stake in Bull. Another company featured in this Chronicles episode, Japan’s NEC, also purchased a 4.4 percent interest.

Just a couple of years later, in February 1996, Groupe Bull sold Zenith Data Systems to Packard Bell, which at that time was the second-largest U.S. seller of PCs. The $650 million deal included a $387 million payment to Bull and a $283 investment from NEC, which not only still owned a stake in NEC–which was now 17 percent–but also owned 20 percent of Packard Bell.

Packard Bell moved into first place in the U.S. market following the acquisition, but the victory was bittersweet for Zenith Data Systems. Packard Bell closed the ZDS production facility in St. Joseph, Michigan, in July 1996 and combined the remaining ZDS operations into Packard Bell’s offices in California. (Groupe Bull continued to own the St. Joseph facility up until 1999.) Packard Bell retired the Zenith Data Systems name in the United States in October 1997, although it continued to be used in Europe for a time. Packard Bell itself was acquired by its minority shareholder, NEC, in June 1996 in a $300 million deal that formed Packard Bell NEC. That company pulled out of the U.S. personal computer market at the end of 1999.

As a final note, the ZDS sale to Packard Bell did not include the original Heath Co. Zenith was never that interested in the Heathkit business and ended development of new kits around 1986. Production of Heathkits ceased altogether in 1992. In October 1991, ZDS reached a draft agreement with a venture capital firm interested in buying Heath, but the deal fell through, which prompted litigation.

Groupe Bull would not sell Heath Co. until 1995. The ultimate purchaser was H.I.G. Capital, a Florida-based management company. H.I.G. ended up breaking up the remaining Heath businesses and selling them off piecemeal. Some of these “parts” were later reassembled into a new business entity called the Heath Company, which attempted to revive the Heathkit business as late as 2022.

Notes From the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original date of February 26, 1987.

- Andrew Czernek was a vice president with Zenith Data Systems from 1981 to 1991. He later worked for Phoenix Technologies and Google. His last reported position was with Lionbridge Technologies in 2008.

- Britt Blaser was a U.S. Air Force combat pilot during the Vietnam War. He was an early investor in Dynamac Computer Products and later served as its CEO. The Dynamac itself made its debut as a prototype in August 1986. As I discussed in an earlier post, the Dynamac was not a Macintosh clone. Dynamac purchased original Macintosh Plus units at a slight discount from Apple and reused those parts to construct its machines. Dyanamac continued in business until 1992. During the 2000s, Blaser shifted his attention to politics, serving as an adviser to former Vermont Governor Howard Dean’s 2004 presidential campaign and later starting the NewGov Foundation and the League of Technical Voters.

- Stewart Cheifet recorded his cold open from a Cathay Pacific check-in desk, presumably at San Francisco International Airport. Based on the signage, it looks like he was waiting for a flight to Hong Kong to record his remote segments for the previous episode on intelligent buildings.

- The Amiga 2000 did launch in March 1987 in Europe and offered the “Amiga Bridgeboard” as an optional accessory to run IBM PC and MS-DOS software. David L. Farquhar published a blog post in 2020 detailing the Bridgeboard. As for the low-cost Amiga, that would be the Amiga 500, which also launched initially in Europe for $649.

- One reason the Coast Guard Academy selected the Macintosh as its mandatory computer might have been its networking capabilities. According to NewsBytes, the academy’s computers were all linked to a mainframe at Dartmouth University in New Hampshire. NewsBytes also pointed out that while a Macintosh may have been an expensive required purchase in 1987, Coast Guard Academy students did receive free tuition, room, and board, as well as a $494.40 monthly stipend to defray expenses.

- The Ford Simulator reviewed by Paul Schindler was the first in a series of disk-based advertisements for the famous car brand. Clint Basinger of the YouTube channel LGR reviewed the second and seventh entries in the series, with the latter published on CD-ROM in 1996.

- Heath Co. didn’t just make computer kits. They also made robots, notably the Hero-1, which was demonstrated in-studio on an early Computer Chronicles episode that I covered.

- Special thanks to Erich E. Breuschke, KC9ACE, and Michael Mack for their 2019 paper, “The History of the Heath Companies and Heathkits: 1909 to 2019,” published in The AWA Review, which helped me fill in some of the gaps regarding the history of Heath Co.