Computer Chronicles Revisited 70 — 101 Macros for Lotus 1-2-3 and Unnamed Lotus Symphony Adventure Game

If you’ve ever watched retro-tech YouTube videos, you might get the impression that the most widely used computer programming language of the 1980s was BASIC. While it’s true that BASIC was how most elementary and secondary school students learned the “basics” of programming, in practice you didn’t see a lot of commercial software developed in the language. Nor was BASIC something that was likely to be used day-to-day in a business.

Indeed, if there was a single most popular business programming language of the late 1980s, it was possible macros for Lotus 1-2-3. The spreadsheet program was at the height of its dominance during this period. And given the original DOS releases of 1-2-3 relied entirely on a keyboard- and menu-driven interface, macros were essential to avoid repeatedly typing the same sequences of commands over and over.

This next Computer Chronicles episode from November 1986 offered a “guide to macros,” not just for 1-2-3 but similar programs of the day. Stewart Cheifet’s cold open was from a local bookstore that displayed a shelf filled with books dedicated to the subject of computer macros. In the studio, Cheifet showed Gary Kildall one of those books, Simpson’s 1-2-3 Macro Library, which was authored by one of the guests on today’s program. Cheifet said there were about 75 macros in the book, ranging from a complete menu-driven database system to a macro to help you write other macros. A lot of people thought of macros as just a series of commands in one keystroke, he noted, but in fact macros had become a form of programming language.

Kildall said that was because macros came from programming languages. He said that in the early days of assembly language it took 50 or 100 instructions to do even the simplest things. So what a programmer would do was put just one name on that sequence of instructions. So every time the assembler saw that name, out came the instructions. In that sense, macros were kind of like a subroutine in the way it looked, but they were much different than a subroutine because they expanded each time you saw the word. What’s happened with application programs was that now a user could add additional structures and commands to the basic program.

Ceramics Studio Used Macros to Manage Payroll

Susan Chase narrated the first remote segment for this episode featuring Evans Ceramics Gallery in Healdsburg, California. Chase said that a pottery operation specializing in the Japanese raku technique seemed like the last place most people would expect to find computers. But Evans was such a place thanks to its bookkeeper, Leslie Arey. (I’m not sure of the spelling on this name, as it was not displayed on screen.)

Chase said that Evans employed 25 people and shipped roughly $100,000 in fine ceramics each month, which required a lot of bookkeeping. Arey said she handled all of the company’s disbursements, accounts payable, vendor lists, payroll, invoicing, and order entry with the computer. As the company had grown, she didn’t think they could have kept their staff to where it was without the computer.

Arey noted that when she started with Evans, she knew nothing about computers except how to turn them on. But then she read the manuals and learned that all she had to do was type in what she wanted the computer to do, hit the right keystrokes, and it would execute all of those keystrokes.

Chase said the process of doing the payroll alone used to take a day. But the macros that Arey programmed into the Enable integrated software package used by Evans allowed her to complete the payroll in just two hours. Arey programmed a macro for any task that took more than five keystrokes. And her work had made automation of the payroll so simple that new office workers could learn the system easily.

What Were Macros All About?

Alan Simpson and Lynne Hughes joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first studio round table. Simpson was the author of the aforementioned Simpson’s 1-2-3 Macro Library. Hughes was a financial analyst with Tymnet, a data communications network based in Cupertino, California, and a subsidiary of McDonnell Douglas Corporation.

Kildall noted that Simpson was both an author and teacher of computer programs. He asked Simpson to “teach us what macros are all about.” Simpson said a macro was designed to save you some keystrokes. For example, you might need to regularly type the time and date into a spreadsheet. By making a macro, you could type a single key that would fill in the current time and the current day. He then demonstrated this in Lotus 1-2-3.

Simpson explained that you could also use macros to extend the built-in capabilities of 1-2-3. For example, 1-2-3 had no way of displaying the day of the week for a particular date. But by creating a macro, you could just have it put in a formula that figured that out.

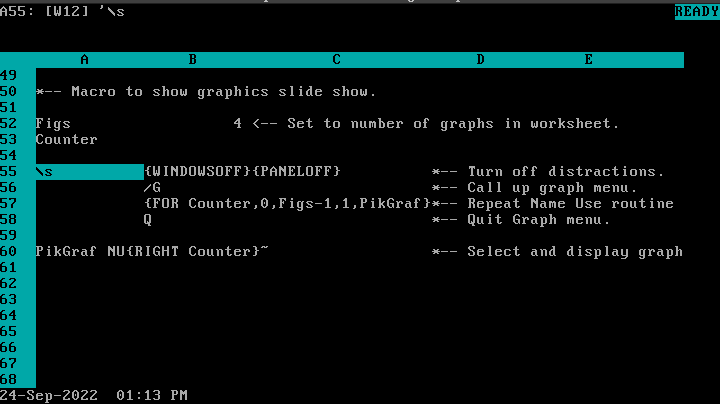

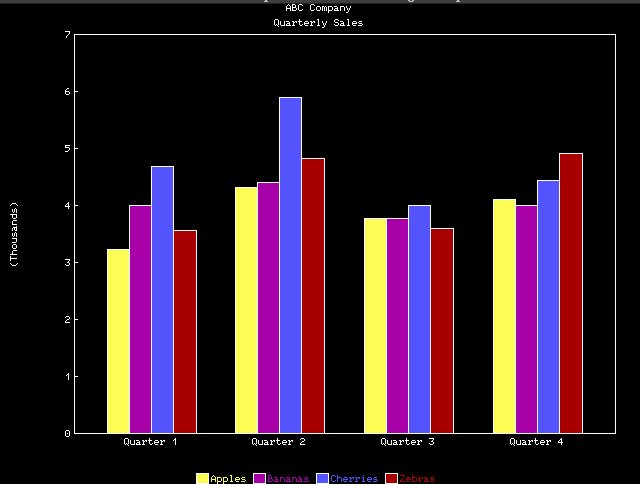

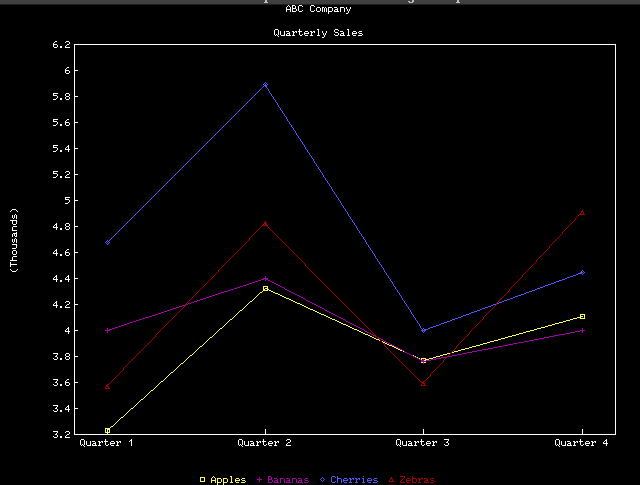

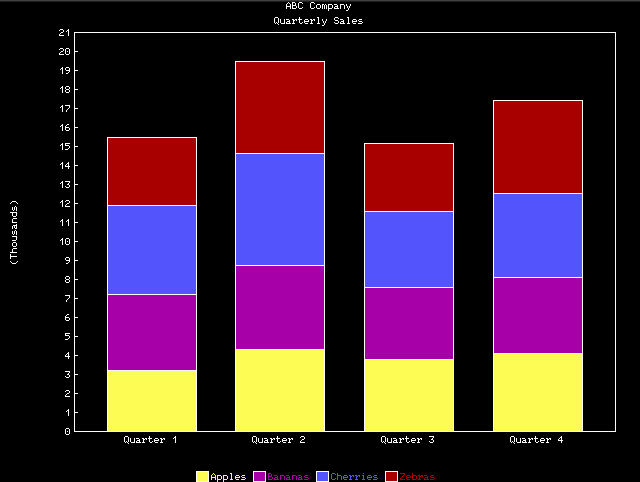

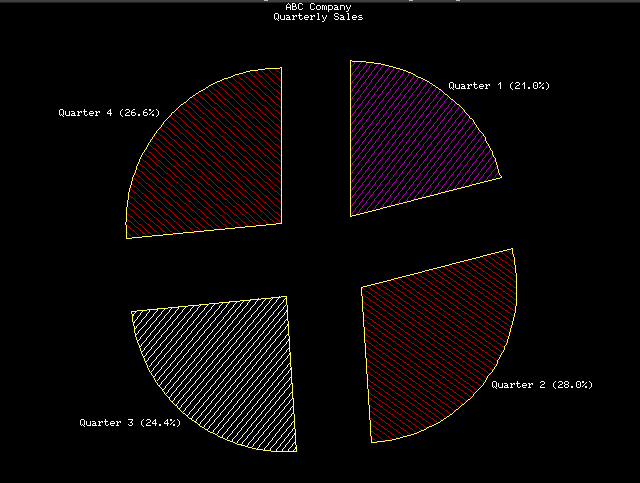

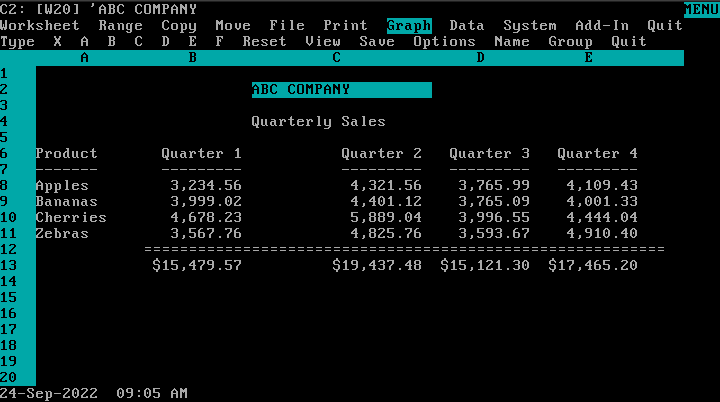

As another example, Simpson said that 1-2-3 could do slides. But this required the user to select a number of menu options to go from one slide to the next. By creating a macro, you could create a slideshow to cycle through a spreadsheet and a series of graphs just by pressing a single keystroke. Simpson then demonstrated this with the following series of slides. (This is a re-creation I made using version 2.2 of Lotus 1-2-3 for DOS, which was slightly newer than the version that Simpson used.)

Cheifet asked Simpson how many keystrokes this saved. Simpson said for this example, maybe 50 or 60 keys. Simpson noted this made macros especially helpful for users who were not experienced with 1-2-3.

Simpson then demonstrated how you could develop customized menu-driven systems using 1-2-3 macros. He showed a sample system that could manage a database. There was a custom menu that replaced the original 1-2-3 menus and allowed the user to perform such functions as adding a new entry to the database, sort entries, prepare mailing labels, or save any current work. This enabled the user to operate the database without knowing any of the underlying 1-2-3 commands, which Simpson said saved hundreds of keystrokes.

Kildall asked Simpson what the “body” of the macro looked like. Simpson said the database macro was fairly large, so it was more complicated than most. But he showed the basic structure. Cheifet observed that what Simpson had done was build an entirely new application with 1-2-3.

Cheifet then turned to Hughes, whom he described as a “normal user of computers” and asked how she wrote a complex macro with hundreds of lines to help with her job. Hughes explained that she worked with a “very large budget structure” for her company’s 1987 operating plan. The company’s structure was so complex that there was an enormous bulk of information. So she set up a database to handle the profit and loss statements. This required defining a worksheet to either enter information into the database or to print off a report to browse the information. If she had to do a separate worksheet for each of the company’s 125 departments, it would take hours. So the macro that she wrote formatted the worksheet for her so she could either enter new information into the database or print off information as needed.

Hughes provided a brief demo of her macro, which was written in VP-Planner, a program similar to 1-2-3 published by Adam Osborne’s Paperback Software International. She showed the entry worksheet, which had a prompt at the bottom to enter the number of a department. The macro would then format a worksheet based on the number entered. The macro prompted for the number of months involved. Anything less than 12 months would then lead to a choice of quarters. The formatted worksheet could then be used to create a department budget for the specified period.

Kildall noted that Hughes learned to program this macro by herself without any help. Hughes said it came down to trial and error. Kildall asked Hughes if she would recommend other people try to do macros themselves. Hughes said absolutely, especially given the time savings.

Kildall said that in the past, macros had performed slow relative to traditionally compiled software code. He asked Simpson if that was still the case. Simpson said it depended. Macros were still slower than programming in C or Pascal, but if you compared it to the time of typing out of commands, macros were much faster. Cheifet asked Hughes how much time she had saved now that she’d written her macro. Hughes said it saved her about 50 percent of her average work day.

Excel Broke New Ground for Macros on the Mac

Susan Chase presented a second remote segment, narrating some B-roll footage of ComputerWare, a Macintosh retailer based in Palo Alto, California. Chase said that within a different operating environment like the Macintosh, macros had a new significance, both in the kind of applications and with respect to the machine’s ease of use. At this ComputerWare store, for instance, a Macintosh users group took advantage of the Mac’s special interface by exploring a range of macros to use within a popular spreadsheet program–Microsoft’s Excel.

Chase said that ComputerWare manager Nicholas DePaul used Excel to organize his staff’s day-to-day schedule. He set up a spreadsheet with a macro that established column and row sizes, headings, and formats. He had substantially reduced the number of keystrokes required to calculate a trend and translated the information into a graph. And when he needed to put an entry into bold or italic script, he could do so with 75 percent fewer keystrokes.

The special natures of macros on the Mac became obvious when you wanted to create one, Chase said, using Excel’s “learn” mode. You just picked out the attributes from the various menus, started the recorder function, and watched the code appear in plain English as you entered each keystroke.

Chase said that macros were meant to take some of the chore out of maneuvering through a program. Why should creating a macro be a chore as well? Although macros had been growing in popularity as more users discovered the advantages–consolidating commands, simplifying keystrokes, and reducing repetition–the full potential had yet to be realized.

Lotus Symphony as a Game Engine?

E. Michael Lunsford and Daniel Gasteiger joined Cheifet and Kildall for the final studio segment. Lunsford was the president of Macropac International, which published a program called 101 Macros for Lotus 1-2-3. Gasteiger was an editor with Lotus Publishing Corporation, a subsidiary of Lotus Development Corporation that published Lotus magazine.

Kildall opened by noting that Lunsford made a business out of selling macros. What exactly was he selling? Lunsford explained that 101 Macros was a software package that came with a manual. He provided a demonstration of a macro that created a new column in a spreadsheet. He also showed a macro that automatically inserted an apostrophe before entering a combination of numbers and text. (1-2-3 required an apostrophe before entering a label including text.) Another macro gave the user a choice of where to go after executing a copy-and-paste function. By default, 1-2-3 returned the user to the cell that was copied, but Lunsford’s macro enabled the user to remain at the pasted cell.

Kildall asked Lunsford if he had a lot of customers for 101 Macros. Lunsford said sales had been very good. He then demonstrated a few more macros, including one that let the user set different home locations (i.e., bookmarks) within a spreadsheet, which made it easier to return to frequently visited cells.

Kildall asked Lunsford if he had any concern about selling the underlying “source code” for his macros as it were. Kildall noted this had previously been an issue with programmers who developed applications in BASIC. Lunsford said his macros were part of a “completely open architecture.” The user could modify and learn from the macros.

Cheifet asked about another macro that Lunsford wrote that let the user do word processing inside of 1-2-3. Lunsford said it was called “My Blank Memo.” It produced a blank memo template and automatically formatted the entered text into paragraphs. Cheifet asked how a user would actually get a macro from 101 Macros into their spreadsheet. Lunsford said you would highlight a blank area of your spreadsheet and select the File Combine option from the 1-2-3 menu and add the range of cells for the macro you wish to import (/FCCN was the sequence of keystrokes.)

Cheifet then turned to Gasteiger, who worked with Lotus Symphony, an integrated office suite that included a word processor and a database. What was the added power you could get out of macros in that bigger universe? Gasteiger said working in an integrated environment gave you just about everything you needed at your disposal for your daily work. He cited communications as an example. Symphony could download information from a mainframe or another source. When you dropped a macro on top of that, the user could parse the downloaded information into a form usable by the spreadsheet. Kildall asked Gasteiger to demonstrate a report-generation macro he’d developed in Symphony. Specifically, he showed how a macro could import names and addresses from a database into a form that made it easy to print address labels.

Kildall then noted that Gasteiger was actually working on an adventure game developed with Symphony macros. Gasteiger said he saw the integrated environment as an ideal place to keep track of all of the different variables involved in creating an adventure game. He showed the opening screen of the game, a Symphony worksheet window with the following introductory text:

You are traveling in a small passenger plane over mainland China in the year 1926. You have been dozing for the past hour or so when a change in attitude of the aircraft causes you to waken.

Looking around, you notice that all the other passengers have vanished, as has the plane’s pilot-presumably, through the open door to your left. You also noticed that the plane is tilted nose-downward and you’re descending at an alarming rate.

Taking stock of the situation, you see that something must have exploded in the cockpit as some of the controls are intact. In fact the only things in the entire chain of the plane that don’t look damages are your seat cushion, your briefcase, and a backpack stored under your seat…"

There was then another window prompting the user, “What do you do?” and a third window enabling the user to enter their response.

Cheifet asked what the advantage was of writing a game in Symphony macros. Gasteiger quipped the advantage was he had Symphony. He said that most of the tools that you needed to make the game were already in the integrated package. If you were using a traditional programming language like BASIC or C, you’d have to create those basic tools as well as the game. So by using Symphony, most of the work was already done for you.

Japanese Companies Teamed Up to Break U.S. 32-Bit Chip Monopoly

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in November 1986.

- The Fall COMDEX show opened in Las Vegas. Cheifet said there were approximately 1,300 exhibitors, and the highlights included a new batch of Intel 386-based computers, low-cost laser printers, desktop publishing software, low-cost PC clones, and a new 5.25-inch disk drive that held 10 MB disks. (A future Chronicles episode focused more in-depth on this COMDEX show.)

- Fujitsu and Hitachi announced a joint venture to develop a 32-bit computer chip following the refusal of American companies to license their designs to Japanese manufacturers. Cheifet noted that Fujitsu recently announced plans to buy 80 percent of American chip maker Fairchild Semiconductor, and the Japanese company already owned 49 percent of supercomputer manufacturer Amdahl Corporation.

- Ashton-Tate, Lotus Development Corporation, and Microsoft were trading at or near their all-time highs on the stock market thanks to analysts predicting strong fourth-quarter results.

- Former Lotus CEO Mitch Kapor was now studying artificial intelligence as a graduate student at MIT. (Kapor never completed his degree.)

- A new report from Cornell University said there was a shortage of PhDs in computer science and engineering, noting that only 400 such degrees were awarded each year to fill more than 1,200 jobs, with salaries ranging up to $100,000.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Scriptor (Screenplay Systems, Inc., $300), a tool for converting text files into formatted scripts for the television and movie industry. Schindler noted that about 2,000 professional screenwriters currently used Scriptor to produce about 70 percent of all television scripts.

- The Wall Street Journal reported that Northeastern Software, a major mail-order software house, had filed for bankruptcy following numerous complaints from people who never received their purchases.

- IBM and Carnegie Mellon University unveiled their plans for creating the “most networked campus in the country.” Cheifet said that the cabling of the CMU campus was now complete, with the goal of networking 10,000 PCs by the end of 1989. IBM and CMU were also involved in a joint venture to develop artificial intelligence applications for PCs.

- A Stanford University study found that top executives were using computers about seven hours per week–much more than previously thought–and 93 percent were using PCs rather than terminals.

- A new computer game based on The Rocky Horror Picture Show was now available for the Commodore 64.

Daniel J. Gasteiger (1959 - 2017)

Daniel Gasteiger died on June 1, 2017. Gasteiger was born and raised in Ithaca, New York, the home to Cornell University, which he also attended. After graduating from Cornell in 1983 he joined the Massachusetts-based Lotus Publishing Corporation.

Gasteiger worked as an editor and columnist at the monthly Lotus magazine for many years. He also served as principal author for The Macro Book: Expert Advice for 1-2-3 and Symphony Users. A few months after his Chronicles appearance, in May 1987, Gasteiger married Stacy Pierce, a fellow Lotus employee who worked in market research.

Gasteiger left Lotus in 1989 to become a freelance writer, editor, and consultant. He continued to write articles for Lotus into the early 1990s, as well as other popular computer magazines like Byte and PC World. Gasteiger also developed The 1-2-3 for Widows Report for Lotus Publishing and in 1992 formed a company with Nicholas Delonas to publish a newsletter called Spreadsheet Consultant.

In 1994, Gasteiger and his family moved from the Boston area to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. He formed a new consulting business, Gasteiger & Associates, and spent the next four years leading the development of “Pisces,” an IBM system used to estimate the costs for bidding on consulting contracts. Gasteiger & Associates also worked on spreadsheet applications for Lotus, Procter & Gamble, ITT Sheraton Corporation, and the Harvard Institute for International Development.

During the 2000s, Gasteiger supplemented his ongoing tech consulting with writing about gardening and transitioning from urban to rural living. He started the blogs Your Small Kitchen Garden and Cityslipper in 2008. In 2011, Cool Springs Press published his book Yes, You Can! And Freeze and Dry It, Too: The Modern Step-By-Step Guide to Preserving Food.

Gasteiger also wrote a regular gardening and food column for The Daily Item, a newspaper based in Sunbury, Pennsylvania. Sadly, the focus of his column shifted in early 2016 when he received a diagnosis of what turned out to be untreatable pancreatic cancer. Gasteiger went on to write 39 columns for The Daily Item detailing his struggles with the fatal disease, with the last column published less than a month before his death.

I could not find any additional information about the unnamed adventure game that Gasteiger demonstrated on Chronicles. It certainly was never released as a commercial product. As far as I know, the single screenshot that Gasteiger showed during his Chronicles appearance is the only surviving proof of the game’s existence.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of November 11, 1986. Based on Alan Simpson’s on-air demo, the studio portions of the program taped on Saturday, November 1, 1986, around 1:30 p.m. (Chronicles normally taped two episodes every other Saturday during this period.)

- Stewart Cheifet introduced Wendy Woods as the presenter of the first remote segment, even though Susan Chase narrated. My guess is that this mix-up was due to the fact that Woods had a baby in August 1986, and she probably went on leave before recording the narration for the remote segments in this episode, leaving Chase to substitute. Chase also substituted occasionally for Stewart Cheifet on “Random Access.”

- Alan Simpson has continued to work consistently as a computer book author and instructor. He’s most recently been affiliated with ed2go, teaching web development courses in CSS, HTML, and Javascript.

- E. Michael Lunsford continued to write computer books into the 1990s. During the 1990s and 2000s, he worked in product development and marketing for a number of companies, such as Palm Inc., EverNote, Sony America, and July Systems. In recent years he’s moved into the world of children’s fiction, authoring a series of novels targeted at middle school readers. He also wrote a play, Scary, Scary Night, a Halloween comedy that he later turned into a musical.

- Evans Ceramics Gallery later changed its name to Evans Designs, Inc. The company dissolved in 2007.

- The Fujitsu purchase of Fairchild Semiconductor never happened. The Los Angeles Times reported in March 1987 that strong opposition within the Reagan administration–notably from Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldrige and Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger–scuttled the deal. Schlumberger Limited, the French company that owned Fairchild, reached a deal later in 1987 to sell its subsidiary to National Semiconductor.

- The company behind Scriptor is still in business. Stephen Greenfield and Chris Huntley started Screenplay Systems, Inc., in March 1982 and released the first version of Scriptor in January 1983, according to their website. As Paul Schindler’s review noted, by 1986 the program had already emerged as an industry standard. For their work, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Greenfield and Huntley an Oscar for Technical Achievement in 1994. Their company, now known as Write Brothers Inc., currently publishes the successor to Scriptor–Movie Magic Screenwriter–and several other script-writing utilities.