Computer Chronicles Revisited 63 — First Shapes, InfoMinder, The Name Game, PLATO, and the Electronic University Network

The second part of Computer Chronicles’ fourth-season look at educational software was something of a grab bag. The September 1986 episode looked at everything from software targeting preschoolers to early efforts at offering college classes online. There was even a return of our old friend the LaserDisc!

Stewart Cheifet opened the program by showing guest co-host George Morrow the VTech Learning-Window Teaching Machine, a “toy computer for kids” that parents could purchase for under $50. It taught kids math and spelling using a voice synthesizer. Cheifet noted that computers had been blamed for putting people out of jobs. Did Morrow think computers could be used effectively to train people for new jobs? Morrow said that he spent a lot of time with user groups and the professionals were using computers now as a transitional tool. The challenge for the industry was putting some “entertainment” into these products to help people make that transition.

Taking College Classes from Your Home (or Horse Ranch)

Wendy Woods presented her first remote segment from the AAG Ranch, a Peruvian horse ranch located in Pleasanton, California, about 35 miles from San Francisco. Woods wasn’t there to talk about horses but rather profiled Lourdes Giovannini, who worked at the family-owned ranch while raising two children, working a job in the city, and taking online college classes through the Electronic University.

Woods said using a modem and software provided by the Electronic University, Giovannini could follow her lessons in business law on her own time, either from home or at work. The course was personalized to her level of prior study. Lessons appeared on the screen much like a traditional online tutorial. But the course was closely based around a textbook.

Like any online database, Woods said, the Electronic University provided students with information resources. But alongside a standard encyclopedia and reference database, the communications link was interactive, much like an electronic bulletin board. Giovannini took her exams on the computer and found out the results about 48 hours later. If she wanted to consult her teacher she could ask to set up an online appointment.

Woods said that educational telecommunications services were clearly limited in their course offerings, although some now offered master’s degrees. But for students faced with time constraints–and adult responsibilities–the opportunity to pursue higher education over a telephone line was a reward in itself.

From Basic Shapes to Fine Art

Mary Cron and Jim Becker joined Cheifet and Morrow for the first studio round table. Cron was vice president of educational products with First Byte, a software publisher. Becker was president of Terrapin Software.

Cheifet opened by noting that in the previous program, they discussed educational software in the schools. Today the focus was on software for the home. Cron’s company produced software for preschoolers. Could kids really handle working with a computer and software when they were just 4 or 5? Cron said yes, and one of the reasons was the advances in interfaces, such as the mouse. The program she was there to demonstrate, First Shapes, only used the mouse for input. So for the child it was a matter of moving the mouse and pressing the button. They didn’t require any keyboard skills.

Morrow asked how the child benefited from this. Cron said the benefits were educational, such as learning geometric shapes while having fun. The computer was a tool that kids could use to experiment with just like they used colored crayons or paints.

Cron then demonstrated First Shapes. In this program, children used geometric shapes to build toys on the screen. This program used voice synthesis technology called SmoothTalker, which was also developed by First Byte, to instruct the child and give feedback.

Cheifet asked Cron about the importance of using speech synthesis in preschool software. Cron said having an auditory component in an educational environment was important, because some kids didn’t learn unless they could “also hear it.” Cheifet jokingly asked if Cron was worried if kids would end up mimicking the synthesized speech and sounding like the computer. Cron said she wasn’t concerned.

Abruptly shifting gears, Morrow turned to Becker and asked for a demonstration of his company’s product, InfoMinder, which was a LaserDisc-based information system running on an Amiga. Becker explained that optical storage allowed you to store a large amount of information. InfoMinder provided a consistent and easy way to find information contained on that optical storage.

Becker demonstrated by using InfoMinder to access a database of information about the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. You could access information about paintings from different time periods located at the gallery. For example, Becker entered a search for “Flemish paintings,” and the software called up specific frames from the LaserDisc that contained matching results. The user could also set the matching images to run as a slideshow.

Morrow clarified that InfoMinder overlaid LaserDisc storage with an information access method. Becker said yes, and he emphasized that the LaserDisc component was just a “small aspect” of the program. The LaserDisc was the “resource.”

Morrow asked if InfoMinder could build an access network that showed the progression of certain schools of art. Becker said you could organize the information any way that you wanted. The system came with its own authoring language and compiler. This allowed you to build a tool to access information in a rapid way. It was simply a matter of how you chose to organize the information. For instance, this particular resource organized the paintings by the names of the painters, e.g., Pablo Picasso.

The “Learning Tool of the Future”

Wendy Woods returned for her second and final remote segment, this time from the Stanford University Medical Center. Woods narrated some B-roll of what she called the “ultimate video game,” or at least the best example of educational software–a videodisc-based training program for medical students. The program, made by San Diego-based Intelligent Images, used video footage and required students to choose the steps necessary to save the life of a stabbing victim. The student used a touchscreen to choose an option. The LaserDisc system then showed the outcome of that choice. If the student made the wrong choice, Woods noted, then the patient “died.”

Dr. Marc Nelson of Stanford noted this tool gave the students “immediate feedback” and a chance to manage a patient’s case, which was typically something they wouldn’t do until very late in their careers. Ann Brewer, a media librarian with Stanford, added that a lot of hospitals and universities were interested in obtaining a similar videodisc-based training system for themselves. She said this was the “learning tool of the future.”

Woods said interactive video also provided the flexibility to fit into the mostly hectic schedules of medical students. Most importantly, these lessons were perfectly suited to this medium. If a student made the wrong choices, they could go back and try again. Real life in the emergency room was not as forgiving, she noted.

These Early FMV Games Were Wacky

Mark Patterson joined Cheifet and Morrow for the next segment. (Jim Becker also stuck around.) Patterson was the founder and president of MindBank, Inc., a Pittsburgh-based software developer. Continuing our videodisc theme, Cheifet noted that Patterson’s company had a program called The Name Game.

Patterson explained his software was focused on business training. He noted that one of the most important skills for a business executive, manager, or salesperson to learn was remembering names. The Name Game taught these skills by offering a simulated environment, in this case having the player be an “undercover agent” attending a party at the U.S. embassy in France. As the player mingled in that party, they met hundreds of people. There was a suspected “deadly plot” and the player’s ability to remember the names of these people was the key to stopping it.

Patterson ran some footage of the game. At random intervals the player would need to recall the name of a particular character from the video footage. If you typed in the wrong name, the character would give you a short lecture about the importance of remembering names.

Morrow asked Patterson about MindBank’s other products. Patterson said they had a whole series of courses on everything from sales management to supervisory skills and technical skills. They were all interactive simulations like The Name Game.

From Mainframes to Micros and Back to Mainframes?

The final segment began with Cheifet talking to Luba Lewytzkyj, who worked in educational marketing with Control Data Corporation (CDC). Cheifet asked Lewytzkyj to explain the PLATO system, which CDC had been marketing for a long time. Lewytzkyj said PLATO was a highly interactive, graphics-based computer education program system. It was “self-paced” and tailored to the needs of individual students.

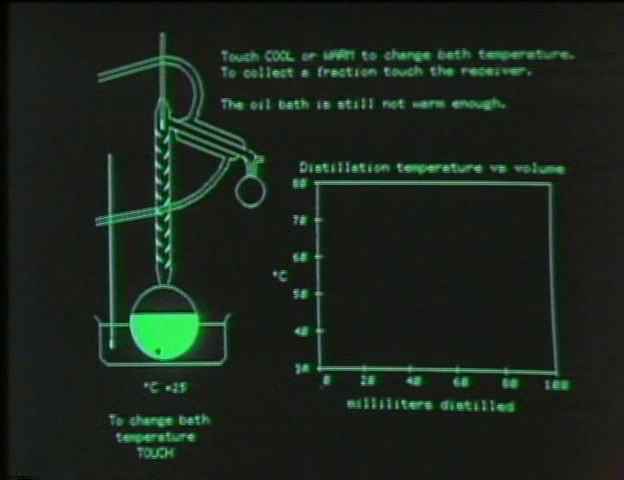

Lewytzkyj showed an example of a PLATO terminal connected to a chemistry lab experiment (see image below). It was a simulation of a fractional distillation experiment. The student would have already used the touchscreen interface to assemble the distillation apparatus beforehand. The objective was to heat the still and obtain a mixture of two chemical compounds. If the student did not enter the correct inputs the simulated experiment would “overheat” and fail. Overall, Lewytzkyj said the PLATO system allowed the student to prepare and understand how to function in a laboratory environment.

Cheifet asked Lewytzkyj to show how PLATO was also used for foreign language instruction. Lewytzkyj demonstrated using Russian. She said there were several hundred hours of materials available on PLATO for a variety of languages, including French, German, and Spanish.

Cheifet noted that PLATO started out on mainframe computers but later moved to microcomputers. Now there was talk about going back to mainframes and modems. Why? Lewytzkyj said that was primarily because schools and homes didn’t have the communications capabilities–such as electronic mail–and lacked the resources to find out how well the student was actually doing on a lesson.

Lewytzkyj then pulled up a Russian lesson on PLATO developed by the University of Illinois. It offered a vocabulary test. The student could also bring up a Cyrillic character set on the touchscreen.

Cheifet and Lewytzkyj then joined Morrow and James Milojkovic back on the main set. Milojkovic was vice president for educational research and development with TeleLearning Systems, Inc., the company behind the Electronic University Network (EUN) profiled during Wendy Woods’ first segment.

Cheifet asked Milojkovic to explain EUN and what it did. Milojkovic said the network connected the personal computers of students to the personal computers of instructors across the country. Cheifet asked if these were “traditional” students or just students going to school on their computers. Milojkovic said they were students who wanted to pursue a degree program and wanted to do so from home.

Milojkovic asked about the time and costs of the EUN. Milojkovic said students paid an enrollment fee to the network and a per-course price that depended on the tuition charged by a particular university. Basically, the student could then take the course at their own pace.

Morrow asked how university faculty actually viewed programs like EUN and PLATO. Lewytzkyj said faculty was becoming more receptive, particularly when they took an active role in helping to develop the computer-assisted instruction material. Milojkovic said EUN followed a different model. They based the development of courses on “master teaching techniques.” This meant EUN directly connected the student to the teacher as opposed to providing a prepackaged lesson like PLATO.

Cheifet asked Milojkovic for a demonstration of the EUN software. Milojkovic explained it was a menu-driven system. Students received messages, lessons, and project assignments from the instructor. Morrow asked how quickly a student could get a response from an instructor to a question or assignment. Milojkovic said instructors were expected to respond within 24 hours or no later than 2 days.

Cheifet asked Lewytzkyj about the future of computers in education. Would we see a massive increase in their use? Lewytzkyj said there would be a greater use of computer-assisted instruction, particularly as the programs became more interactive and provided the kind of individualized instruction that students needed in a non-traditional environment.

Apple Set to Debut “Yuppie” IIgs

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access” segment, which he recorded in September 1986.

- The new Apple IIgs was due in stores any day now. The basic machine would sell for just under $1,000 and include 256 KB of RAM and enhanced graphics and sound modes. Cheifet noted the IIgs had two high-resolution graphics modes and could handle 15 voices simultaneously through its custom sound chip. Apple said the IIgs was compatible with “most” Apple II software. The company would also sell an upgrade kit for the Apple IIe that turned it into a IIgs. That upgrade would cost $500.

- The full Apple IIgs system with a disk drive and color monitor would cost around $1,800. Cheifet noted the machines were being built in Singapore and the first 50,000 units would carry the signature of designer and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

- Cheifet said early reviews of the IIgs were positive, although some reviewers said the graphics were not as good as the Amiga. Meanwhile, Atari said the “high price” of the IIgs did not make it a serious threat to its 1040ST. Indeed, Atari President Sam Tramiel dismissed the IIgs as a “yuppie machine.”

- Atari Corporation was reportedly planning to go public with a $50 million stock offering.

- IBM slashed prices on PCjr software and accessories. Cheifet noted there were about 400,000 existing PCjr users. The price of the PCjr version of Lotus 1-2-3 was reduced from $300 to $99.

- IBM also announced it would reduce its workforce by several thousand people through a new “retirement incentive program,” allowing the company to maintain its traditional “no layoffs” policy. Cheifet said Hewlett-Packard was doing the same thing, using a voluntary retirement program to eliminate 1,500 positions.

- Lotus planned to start sales of Lotus 1-2-3 in Japan, targeting the NEC 9800 computer and the IBM 5550 series.

- Online Access Guide, a new bimonthly magazine for modem users, was due out later in September 1986.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Q-DOS (Gazelle Systems, $30), a DOS file manager program that displayed a diagram of directories and subdirectories.

- Computer scientists at the University of Florida were working on the “mind link,” i.e., a way to have computers communicate directly with a human brain.

- Harvard University professor Anthony Oettinger coined the term “compunications,” a combination of computer and communications. Etinger predicted the term would describe future combinations of computer and communications companies, such as “IBMCI” (IBM + MCI) and “AppleT&T.”

- A new study of bulletin board users found there were about 400,000 regular BBS users in the United States and about one-third of them now used 2400 baud modems. The average BBS received 45 calls per day.

- Operators of France’s Minitel system were concerned about the growing popularity of prostitution and pornography on the online system.

MindBank Struggled as Videodisc Market Failed to Take Off

As I noted in my introduction, this episode was something of a grab bag without a coherent theme. So I’ll briefly focus here on just one guest, Mark Patterson of MindBank, Inc. Patterson got his start in the business quite young. In fact, he founded MindBank in 1982 while still studying for his MBA at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. Patterson told The Pittsburgh Press in June 1983 that he started MindBank primarily to develop computer-based training systems for the banking industry. But he didn’t have an actual product at this point.

A lack of product didn’t prevent Patterson from attracting capital. A few months later, in October 1983, the Press reported that Patterson had raised $625,000 for MindBank thanks to assistance from the Enterprise Corporation, a nonprofit startup fund established by Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh. Fast forward to August 1986, and MindBank finally sold its first six computer training courses at $2,400 apiece to a Milwaukee insurance company. Accounting giant Price Waterhouse also announced it would work with MindBank to develop a “series of financial and general management videodisc training courses.” MindBank now employed 13 people and Patterson predicted product sales of $1 million by the end of 1986, according to the Press.

With Price Waterhouse’s backing, MindBank also established a training center in downtown Pittsburgh in late 1986. Dubbed the “Mastery Center,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported MindBank planned to offer 15 on-site courses (at rates of $300 to $500 per student) with another 48 promised by the end of 1987. The Name Game demonstrated on Computer Chronicles was one of these courses. Patterson claimed it cost about $250,000 to develop each course.

When Patterson appeared on the show, he was still publicly bullish on the future of videodisc-based training programs. This didn’t last long. By June 1988, MindBank struggled with cash flow problems. The Pittsburgh Press said Patterson was forced to cut his staff by half and close the Mastery Center. A planned interactive budgeting course–another part of the Price Waterhouse joint venture–was 18 months behind schedule. One ex-employee told the paper they were “very surprised” that MindBank was even still in business.

Patterson maintained an optimistic tone but conceded to the Press that “the videodisc market never did take off like many people said it would.” (Presumably, Patterson was one of those people.) He blamed the expense of the videodisc system itself, which still cost about $10,000 in 1988.

About a year later, in May 1989, the Press reported that MindBank had started to rebound, thanks largely to its new Real Estate Management System (REMS), a $25,000 hardware-software for interactive property management. MindBank developed REMS under a $110,000 contract from the Greater Chicago Water Reclamation District, which used REMS to “manage several hundred properties over a 20,000-acre area,” according to the Press. Patterson said REMS helped turn MindBank into a profitable corporation for the first time ever in late 1988.

While the news reporting on MindBank dried up after the late 1980s, the company still exists, at least according to Pennsylvania records. As best I can tell, Patterson continued running MindBank as essentially a software consulting business during the 1990s. Patterson himself relocated to Virginia at some point. In recent years he launched another startup called Brainfire.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of September 18, 1986.

- Luba Lewytzkj had a long career in sales and marketing after leaving Control Data Corporation, working at Pearson, Microsoft, and Atomic Learning among other companies. Since the 2010s she’s worked as a consultant based out of Minnesota.

- The AAG Ranch seen in Wendy Woods’ first report discontinued its horse breeding operation in 1988. The Giovanni family later opened the La Equestrian Center in 2000, where Lourdes Giovanni is still the on-site manager, according to the center’s website.

- The First Byte, Inc., was incorporated in 1982. During the mid-1980s, First Byte published a number of educational titles, which were distributed by Electronic Arts. But First Byte was probably best known for its speech-synthesis software SmoothTalker, which was available on a number of 16-bit machines. The company later shifted towards speech synthesis for MS-DOS computers. Davidson & Associates, a major player in the educational software market at the time, acquired First Byte in December 1992.

- Mary Cron apparently left First Byte later in 1986 to start her own software company, Rymel Design Group, which produced titles such as Davidson’s Kid Keys, an animated typing tutor program for elementary school children that was published by Davidson & Associates. According to a 1994 Newsweek profile, Cron’s company employed mostly female software artists and designers. Based on California corporate records, Rymel remained in business until around 1999.

- I didn’t find much about Jim Becker or his company Terrapin Software. InfoMinder was distributed as a commercial product by a Texas-based company, Byte by Byte (not to be confused with First Byte). Bob Lindstrom noted in a December 1986 review that InfoMinder was “one of the few” native applications produced for the Amiga at that point. Byte by Byte was “advertising the product as an ideal gateway to CD-ROM-based information,” and Lindstrom agreed that “InfoMinder has potential in a wide variety of information storage and retrieval applications.”

- The PLATO system’s appearance on Computer Chronicles actually occurred fairly late in the system’s life. The original PLATO was created at the University of Illinois back in 1960. The commercial rights to the system were licensed to Control Data Corporation three years later, in 1963. Jimmy Maher of the Digital Antiquarian offered a good overview of PLATO and CDC’s role in marketing the system in a 2012 post.

- The Electronic University Network (EUN) was the brainchild of Ron Gordon, whose biggest prior claim to fame was his stint at the original Atari, Inc., under Nolan Bushnell. Gordon joined Atari in 1972 to head up its international marketing operations and briefly served as the company’s president from 1974 to 1975, leaving prior to the sale of Atari to Warner Communications. He launched TeleLearning Systems, the parent company of EUN, in 1982. EUN actually continued well into the 1990s, eventually offering its courses through America Online. In 1998, EUN merged into Durand Communications. Ernie Smith of Tedium published a more detailed article in 2019 about TeleLearning and EUN’s legacy in the online education market.

- Atari Corporation did go public on November 7, 1986, selling 4.5 million shares at $11.25 each, for a total offering of $50.6 million. Jack Tramiel and his family still retained 53 percent of the company. Warner Communications, which sold the home video game and home computer assets of the original Atari, Inc., to Tramiel in July 1984, was still the second-largest shareholder of Atari Corporation at the time of the public offering.

- I wonder if France ever managed to lick that whole “people using computer networks to look at porn” problem.