Computer Chronicles Revisited 61 — The FPS-264, ELXSI 6400, Sequent Balance 8000, and the WARP Project

Since the mid-2000s, just about every personal computer made contains a multi-core and/or multi-threaded CPU. These are both practical applications of parallel processing technology, which was still in its infancy back in March 1986 when this next Computer Chronicles episode aired. At this point, parallel processing was largely the domain of expensive “super” minicomputers that were marketed as less-expensive alternatives–relatively speaking–to traditional mainframes.

Stewart and Gary Playing with Their Trains

In his cold open, recorded at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University, Stewart Cheifet showed a video camera that was part of a computerized vision system attempting to mimic the human brain by processing millions of pieces of information in milliseconds. Sequential computers couldn’t handle that kind of speed, he said, so computer scientists needed to develop computers that worked more like the human brain in terms of parallel processing.

Back in the studio, Cheifet and Gary Kildall used toy trains to illustrate the concept of parallel processing. Cheifet explained that in a sequential computer you basically had one “train” on one “track” carrying one instruction or piece of information. But in a parallel system you could have two or more engines, each carrying some information, down separate tracks, meaning the job could get done twice as fast.

Cheifet asked Kildall if he was “on the right track” with that analogy. Kildall said it was a good model. The basic idea was to take a complicated task and break it down into smaller, independent tasks that could be carried out at the same time. For example, if you wanted to move 1,000 people down that train track, you could use several trains to move them down one track by making separate trips. Or you could have several trains running on parallel tracks take all 1,000 people down the track at nearly the same time. The problem was how to coordinate the trains.

Kildall added that personal computers already ran multiple processes in parallel using different processors. For example, there was one microprocessor monitoring the keyboard and recording keystrokes, another in the printer that buffered and printed data, and a CPU coordinating all those processes independently.

64-Bit Machine Offered “Remarkable” Graphics to Researchers

Wendy Woods’ first segment offered a broad overview of the concepts behind parallel processing. Over some B-roll footage, Woods said that towering over the minis and mainframes were supercomputers like the Cray X-MP. Of course, the Cray cost tens of millions of dollars. But the widespread interest in parallel architecture could change that.

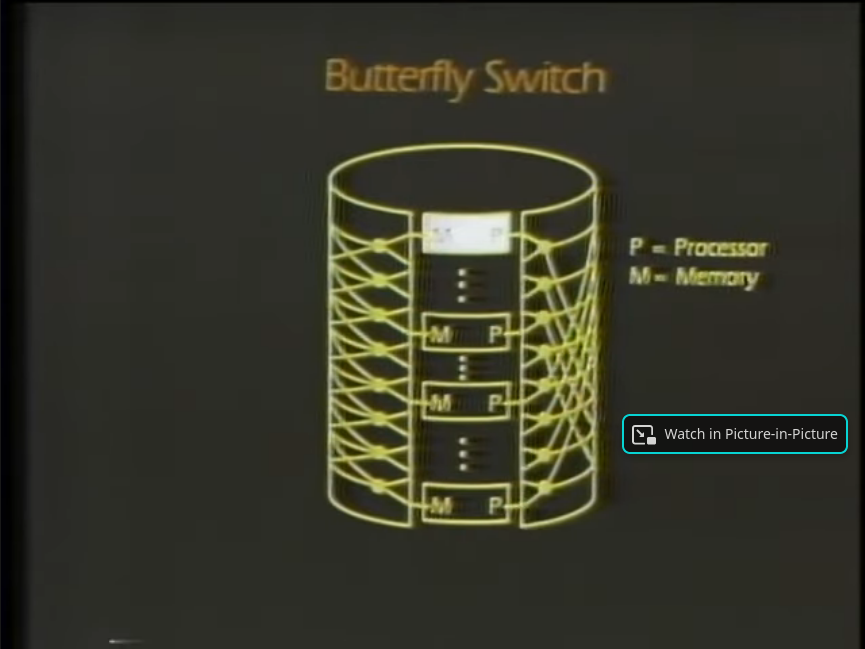

Parallel processing–i.e., the dividing up of computations between processors working in unison–could be accomplished in different ways, Woods said. The data bus was the most common method but only effective for a limited number of processors. The distributed crossbar was another way to divide up the processing, although the need to interconnect each processor with one another placed a practical limit on that system as well. Finally, there was the butterfly switch network, which could expand the crossbar to include up to 256 processors (see below).

But regardless of the method used, Woods said, these multi-processor “superminis” were giving new number-crunching power to specialized users. For example, the University of California-San Francisco recently installed a Floating Point Systems FPS-264, a parallel processing machine that the school used for molecular modeling studies. The 64-bit machine was capable of 38 million floating point operations per second (FLOPS), which could reduce a night’s worth of calculations to just a couple of hours.

Woods noted the FPS-264 produced some of the most remarkable graphics ever seen on a computer (see below).

Could Parallel Processing Bring Computers Closer to the Human Brain?

Dr. Howard Resnikoff and Dr. Eugene Brooks III joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first of three studio round tables. Resnikoff was a visiting scientist at MIT specializing in biological information processing and also worked with Thinking Machines Corporation, a supercomputer company. Brooks was a physicist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Kildall opened by asking Resnikoff what his work in biology had to do with parallel processing. Resnikoff said the most “proficient” parallel information processors were biological organisms. For example, if you drove your car down the street and a child ran out in front of you, within one-tenth of a second your brain would respond and have your foot aimed at the brake. To break it down, light hit your eye and traveled up the optic nerve. Your brain then created a plan, compared the information with stored knowledge, and sent signals to your motor system to move your muscles. The neurons in your brain switched in a millisecond and thus required parallel processing.

Kildall turned to Brooks and asked him a similar question about how parallel processing applied to his work. Brooks said parallelism did two things. First, it reduced the cost of using simulations to solve a problem. That is, it allowed the lab to use several cheaper computers in running that simulation as opposed to one more expensive computer. Second, parallel processing reduced the time it took to run the actual simulation. In order for simulations to be useful, the physicist had to get answers back quickly enough so they didn’t forget what problem they were trying to solve.

Kildall asked for an example of a typical physics problem. Brooks said weather simulations and simulations of the deformation of metals were two common examples. Kildall interjected and asked how parallelism might specifically be useful in a weather simulation. Brooks said that type of simulation required dividing a physical space into a large number of zones. The process of updating the physical characteristics of each zone could then be done in parallel rather than having to do them one-at-a-time in sequence.

Cheifet asked Brooks how much faster parallel processing actually worked. Brooks said the factor in speed was difficult to ascertain. If you updated thousands or millions of data points in something like a weather simulation, the cost of organizing all those parallel computations could interfere with the effective use of parallelism. So there was only a certain range of parallelism that you could exploit efficiently.

Cheifet asked Resnikoff if he could see parallel processing applied to a field like artificial intelligence. Resnikoff said we’d begun to see that already. He cited machine vision (which Cheifet mentioned in his cold open) as one potential application. Resnikoff said you had to realize the amount of computing resources required for such tasks was much greater than any sequential computer could offer today. The human eye, for instance, received the equivalent of 2,500 MB of data per second. No computer available today could deal with that.

Cheifet noted that Brooks worked with a parallel processing machine called the Hypercube when he worked at the California Institute of Technology. What approach did the Hypercube use? Brooks said it was a “message-passing” architecture where you used multiple CPUs connected to each other. These CPUs then sent “computer mail” to one another to get the work done. The data of the algorithm had to be distributed among all the CPUs by the programmer.

Cheifet asked Resnikoff to elaborate further on the human brain as an analogy to a parallel computer. Resnikoff said this was a “very complicated question.” He noted that we still knew very little about how the brain actually worked. Some scientists believed the brain may contain 10 to the 12th power number of neurons. Electronics would not build machines that complex, he said, so the more fundamental question was how to structure the programs, which was where most progress would be made.

Parallel Personal Computers by 2000?

Wendy Woods’ second segment focused on the ELXSI 6400, a parallel processing minicomputer developed by Elxsi Corporation in San Jose, California. Woods said Elxsi’s president, P. Appleton Jones, predicted that all computers would be parallel processing machines by the year 2000. As for the 6400, it was currently capable of running 12 CPUs simultaneously. Jones told Woods that Elxsi had already sold the ELXSI 6400 to 60 major customers. For example, he said General Motors was now using parallel processing to design car bodies, and the semiconductor industry was doing the same with respect to chip design. He said parallel processing allowed these companies to obtain the same calculations for one-quarter the price of using a single-processor computer.

Woods said that parallel processing didn’t come cheap. A top-of-the-line ELXSI 6400 cost nearly $3 million. But Jones said he expected the prices would come down as the industry realized the potential. He reiterated his view that personal computers used in business would be parallel machines within the next 10 to 15 years. It was the “natural step” to take once you accepted the limitations of sequential processing.

Woods said Elxsi sold $22 million in hardware in 1985, which wasn’t bad for a company pioneering a new technology. And in 1986, the company not only expected to break even but also show a profit over its initial investment. After that, the sky was the limit. (Spoiler: It wasn’t.)

Sequent Displayed the Power of a Dozen CPUs

David Rodgers, vice president of engineering for Sequent Computer Corporation, joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Dr. Howard Resnikoff also remained with the panel.

Kildall asked Resnikoff if the train analogy used in the beginning of the episode was really an accurate model for parallelism. Resnikoff said it was a good model, albeit not perfect. The more complicated the problem, the more the processors had to communicate with one another, and the topology of the network was thus critical.

Cheifet asked Rodgers for a demonstration of his company’s parallel processing machine, the Sequent Balance 8000. (The actual machine was running to the side of the studio; a display monitor was on the desk.) Rodgers said his on-screen demo showed a sample computation–the Mandelbrot set–which could be divided into parallel segments. The Balance 8000 had a total of 12 processors, which meant the individual segments could be processed 12 at a time. To illustrate the difference in speed, the Sequent calculated the Mandelbrot set starting with just one processor, then two, and finally all 12.

Rodgers said that someone generally wanted to accomplish one of two results with parallel processing. Either they obtained a decrease in run-time–they obtained the results more quickly–or there was an improvement in throughput.

Kildall asked for more information about the Sequent’s architecture and how it differed from, say, the Hypercube discussed earlier with Eugene Brooks. Rodgers said the Hypercube was an example of a “connection” machine. i.e., a network of computers talking to one another but not sharing the same memory. In contrast, the Balance 8000 was a “closely coupled multiprocessor,” where all of the CPUs shared access to the same data at every instant in time. One would use a connection machine for a problem where the rate of communication among the processors was lower and the distribution of data was higher. Conversely, with closely coupled machines one worked on problems where there was more frequent intercommunication and the volume of data was larger.

Kildall asked if there was any application of this technology to personal computers. Rodgers said the recently announced IBM RT PC allowed for parallel computation. Kildall brought up graphics as another application. Rodgers said that many machines used for complex tasks like graphics relied upon functional distribution.

Cheifet asked Resnikoff about the approach taken by his company, Thinking Machines. Resnikoff said Thinking Machines made a connection machine with 64,000 processors, each of which was a relatively simple one. For a machine like that, which operated in a special control mode, graphics and image processing problems could be treated in a manner similar to the 12-processor Sequent 8000 but on a “much more massive scale.”

Cheifet asked Rodgers to elaborate on the specific applications of the Sequent machine. Rodgers said in terms of runtime applications it was much along the lines of the demo he showed–graphical applications and simulation of physical systems. The throughput-oriented applications tended to focus on transactions, such as large numbers of people accessing the same database.

Carnegie Mellon Researchers Proceeding at Warp Speed

Stewart Cheifet presented the third and final remote segment for the week, a report from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), where he also did the cold open at the beginning of the episode. Cheifet quipped that on Star Trek, when Captain Kirk told Scotty to set the engines at “warp speed,” you knew that meant he wanted the Enterprise to go fast. Similarly, when CMU started its WARP Project, it wanted computers that wanted to go fast–which meant using parallel processing.

Cheifet said the computer scientists at CMU were trying to build a parallel machine that could provide the computer power needed for vision processing, which was essential to the future of robotics. Because vision processing was easily divided up into separate computations, it seemed ideal for parallel processing and the localized memory approach of the WARP machine.

Vision processing required tremendous speed just to do the filtering necessary to eliminate erroneous images, Cheifet said, such as shadows or debris. A vision processor thus needed to perform 20 calculations per-pixel per-second. With a typical matrix of 250,000 pixels, that meant 5 million computations per second–far beyond the speed of today’s sequential computers.

Dr. Hsiang-Tsung (H.T.) Kung, the head of CMU’s WARP Project, told Cheifet that building the machine was the easy part. The difficult part was figuring out how to actually use the hardware. Kung’s approach was therefore to build a parallel machine with a very simple architecture, which made the machine easier to program and build more complex software on top of.

Cheifet said that to be useful in vision processing, the WARP machine not only had to recognize what it saw, it had to first translate the distorted images from its lens into the normal linear aspect ratio. And that computation required tremendous speed, because the image was constantly changing as the computer scanned its environment.

The usual method of attaining computer speed, Cheifet noted, was the supercomputer approach used by Cray. But Kung said the parallel approach was superior. He told Cheifet this was the difference between doing things very fast on a very big piece of hardware (the supercomputer) versus doing it on a small piece of hardware (a parallel machine). He added the smaller machine would also be more adaptable for new uses as it could be easily moved to the places where it was needed.

Cheifet said one of the next big steps for the WARP Project was to use very large scale integration (VLSI), which would reduce the size of the necessary processor boards to a mere 2-by-4 inches. With that level of integration, Kung said it was only a matter of time before you found parallel processing in your microcomputer. That meant personal computer users would have access to technologies like vision processing.

Growing the Commercial Market for Parallel Machines

For the final studio round table, Craig Mundie and Jeffrey Canin joined Cheifet and Kildall. Mundie was a co-founder and vice president of product development at Alliant Computer Systems, a Massachusetts-based manufacturer of parallel systems. Canin was an analyst with Hambrecht & Quist, a San Francisco investment bank.

Kildall asked Mundie about Alliant’s approach to parallel processing. Mundie said it differently slightly from that of Sequent or the Hypercube. Alliant’s goal was to produce a range of products that would be used in engineering computing within a price range of roughly $100,000 to $1 million. More importantly, he said the goal was to provide a form of “transparent” parallel processing, which meant people with existing applications–typically coded in FORTRAN–could port them from existing single-processor machines to run on Alliant’s parallel processing machine without needing to redevelop their application.

Kildall said it seemed difficult to pull this off, given that a FORTRAN program typically wasn’t written with parallel processing in mind. Mundie agreed that it was difficult. It required some state-of-the-art development, both in compiler technology and the actual low-level machine architecture.

Kildall asked Mundie what a sample customer for Alliant looked like. Mundie said a number of Fortune 500 companies, specifically those with research and development labs, had purchased Alliant machines. Specifically, he said companies in telephony and aerospace used parallel processing for a range of applications from finite element modeling to speech synthesis and analysis.

Cheifet turned to Canin and asked him if there was now a viable commercial market for parallel processing machines. Canin said we were already starting to see some commercial successes in this market. It had been very long in promises and a lot of vendors were now trying to get into the market.

Cheifet asked Mundie about the consequences of parallel processing for the typical PC user. Mundie said one consequence was that technical computing was now becoming “bimodally distributed.” (In other words, technical problems could now be designed and solved on an individual workstation.) He added that thanks to networking, parallel machines with much higher performance were now being used in a server role.

Kildall asked if we’d need to change how we program to use parallel machines effectively. Mundie said it depended on the class of machine. Something like the Hypercube would probably require new programming languages or at least new programming techniques. Alliant’s goal was to get “reasonable efficiency” as you added more processors, even for older languages like FORTRAN. So he thought both approaches would be used going forward.

Because we haven’t brought up the Japanese in awhile, Cheifet asked how their efforts in parallel processing compared with the work going on in the United States. Canin said the American companies were taking the lead in this particular market. The bulk of the Japanese market was at the higher end, i.e., supercomputers.

Cheifet said his impression of parallel processing was that the hardware was ahead of the software. Did more needed to be done to find ways to use this technology? Mundie said there had been significant progress lately in both hardware and software. Kildall noted that the emphasis in parallel processing seemed to be on scientific uses. Would we start to see more business applications? Mundie said yes, especially in the area of database management. He added that companies like Alliant and Sequent focused on the high-performance engineering and scientific area partly due to market conditions, and partly because the technology was more readily applicable to problems in those fields.

IRS Selected Zenith to Fulfill Portable PC Needs

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which he recorded in March 1986.

- Scientists in the United States and the Soviet Union reached a tentative agreement on a new computer network that would link the Soviet Institute for Automated Systems in Moscow with the New Jersey Institute for Technology. Cheifet said this network would allow Soviet and American scientists to share databases and work together on research projects.

- IBM said its recent price cuts and a “soft market” for capital spending would reduce its expected earnings for the first quarter of 1986.

- The IRS awarded a $28 million contract to Zenith to provide its Z-170 portable computers to the agency. Cheifet said the decision to go with a machine with a 5.25-inch disk drive would help the larger format stay ahead of the 3.5-inch microfloppies.

- The U.S. Senate Governmental Affairs Committee released a report criticizing the federal government’s computer security practices. The report said there was “inadequate screening” of computer personnel and a lack of planning with respect to risk analysis.

- The National Science Board released a report stating that U.S. high tech research was basically in good shape but warned of the increasing role of the military in funding research. Cheifet said the biggest weakness identified by the report was a lack of math and science teachers at the high school level.

- A high school in Grand Rapids, Michigan, was now teaching industrial robotics.

- A Fairfield, Iowa, programmer released a speech synthesis program called Babble 123, which was designed to talk in a “calming and loving way” to farm hogs.

Parallel Processing Worked…Even If These Four Companies Did Not

This episode featured four companies involved in the parallel processing market in 1986: Alliant, Elxsi, Floating Point Systems (FPS), and Sequent. None of them exist today. Well, one of them still exists, but not as a company having anything to do with computers.

Elxsi Somehow Morphed from Cutting-Edge Computer Company Into Running Diners

The company that still kind-of exists is Elxsi. Joseph D. Rizzi and A. Thampy Thomas founded the original Elxsi in 1979 to produce “superminicomputers” capable of running both UNIX and the company’s own proprietary operating system. By 1984, the company had sold about 40 computers total. That may not sound like much but keep in mind these superminis often had seven-figure price tags. For example, in March 1984 Australia’s Department of Defence purchased an ELXSI 6400 for $1.6 million, according to the Sydney Morning Herald.

In 1985, Elxsi merged with Trilogy Ltd. I previously mentioned this deal in a post about a Chronicles 1984 episode where Gene Amdahl appeared as a guest. Amdahl, one of the key people behind IBM’s success in the mainframe market, left Big Blue in 1970. He subsequently launched a couple of different startups in an attempt to compete against IBM. Trilogy was one of those efforts.

An unidentified Trilogy employee told the San Francisco Examiner in March 1985 that the company had “given up on its attempt” to develop technology that could dislodge IBM’s supremacy in the mainframe market. But Trilogy was still flush with cash, so Amdahl and his executives decided to invest in Elxsi’s parallel processing machines instead. Amdahl continued as chairman of the combined company–which used the Elxsi name–until 1989, when he resigned in favor of original Elxsi co-founder Rizzi.

As it turned out, Amdahl jumped off a sinking ship. The company had not turned a profit since the first quarter of 1988. In August 1989, Elxsi announced “significant” second quarter losses and laid off 50 percent of its staff. This ended Elxsi’s manufacturing operations in the United States. Elxsi continued to conduct operations in Singapore as part of a joint venture with the India-based Tata Group.

The Tata-Elxsi joint venture broke off at this point into its own entity, which actually continues to the present day. Meanwhile, Elxsi sold what was left of its U.S. hardware and software business to Minneapolis-based National Computer Systems, Inc., in November 1989.

That was the end of Elxsi as a computer business but not of the company itself. In September 1989, Milley & Co. purchased a 20 percent stake in Elxsi, which quickly rose to a controlling interest. Milley was a Connecticut-based investment company run by Alexander “Sandy” Milley. Apparently, Elxsi still had one valuable asset left in the form of tax breaks. (I couldn’t find a more specific explanation of what these tax breaks were or how they worked.)

Sandy Milley decided to use the shell of Elxsi–and its lucrative tax breaks–to acquire several profitable (but under-performing) companies via leveraged buyouts. In 1991, the Milley-controlled Elxsi purchased a group of 42 restaurants from Marriott Corp., operating under the Bickford’s Family Restaurant and Howard Johnson’s brand names. The following year, Elxsi bought CUES Inc., a company based in Orlando, Florida, that manufactures surveillance cameras and repair equipment for sewer lines.

Brad Kuhn, writing for the Orlando Sentinel in 1995, said that Elxsi was at that point primarily a restaurant company–at least in terms of revenues–although Milley focused most of his energies on running the CUES side of the business. Kuhn noted that Milley was never able to fully exploit the original Elxsi tax breaks as the market for leveraged buyouts had slowed.

Milley continued to run his unholy restaurant-and-sewer-camera company well into the 2010s. In April 2018, North Carolina-based SPX Corporation purchased Elxsi and merged it into a subsidiary that retained the Elxsi name. This deal only covered the CUES part of the business. The Bickford’s chain is now down to just three restaurants in Massachusetts. Milley still owned those remaining restaurants as of late 2018 but I’m not sure about the current ownership situation.

Mundie Enjoyed Long Career at Microsoft Following Alliant’s Demise

Alliant Computer Systems only lasted a decade. Craig Mundie co-founded the company with Ron Gruner and Rich McAndrew in 1982. This wasn’t mentioned in the episode, but Jeff Canin’s firm, Hambrecht & Quist, was one of the venture capital funds that backed Alliant’s initial business plan. (Another backer was former Chronicles guest John Doerr of Kleiner Perkins.)

According to Jessica Livingston, who interviewed Gruner for her 2007 book Founders at Work: Stories of Startups’ Early Days, Alliant raised an initial $30 million to build “very high-performance computer systems that provided a growth path from [Digital Equipment Corporation’s] VAX lines of machines, which were topping out at half a million dollars.” It took three years for Alliant to actually bring a product to market. Alliant subsequently went public in December 1986 with Hambrecht handling the offering along with Morgan Stanley.

Gruner told Livingston that Alliant grew quickly–reaching a market valuation of nearly $500 million–but then the company “hit the wall” for a couple of reasons. First, Alliant was late in shipping one of its next-generation computers. And by that point, high-performance computers had become “the ultimate commodity,” with competitors quickly exceeding Alliant’s price-performance ratio. Second, the end of the Cold War led to a decline in purchases from defense contractors, who made up a significant portion of Alliant’s customer base.

In February 1991, Alliant’s board fired Gruner as chief executive officer. Mundie, by then the company’s president, took over the CEO’s role as well. Alliant continued to introduce new products, including a November 1991 announcement of a “massively parallel supercomputer” with 800 Intel CPUs that cost $16 million. But it was apparently too little (or perhaps too much) too late. In May 1992, Alliant laid off 75 percent of its employees and filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The company never emerged from bankruptcy, however, and ended up selling off its remaining assets.

Mundie left Alliant in December 1992 to join Microsoft as general manager of its advanced consumer technologies division. He would spend more than 20 years at the company, retiring as chief research and strategy officer in December 2014. Mundie subsequently formed a consulting company.

Floating Point Research Fell to Cray–and Ultimately Silicon Graphics

Floating Point Systems began in 1970. As the name suggests, FPS originally designed and manufactured specialty minicomputers that performed complex floating-point calculations. Based on a 1978 Barron’s report discussing the company’s public offering, the major uses for FPS machines included “radar and sonar processing, seismic analysis for energy exploration and, not least, CAT scanners.”

By 1986, the Oregon-based FPS claimed to have the “world’s fastest supercomputer,” thanks to its parallel processing technology. But sales of these new machines, known as the T-series, were slow to say the least. By the end of 1989, FPS stock fell to $1.83 per share, which represented an 80 percent drop from the company’s initial public offering 10 years earlier. The New York Stock Exchange suspended trading in FPS altogether in September 1991. FPS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and the company’s founder and CEO, C. Norman Winningstad, retired a few days later.

Shortly after Winningstad’s departure, supercomputer giant Cray Research signed a letter of intent to purchase FPS. The negotiations were apparently contentious, with Cray publicly backing out of the deal in mid-November 1991 before finally reaching an agreement with the judge overseeing the bankruptcy case. In December 1991, Cray formally acquired the assets of FPS for $3.25 million. Steve Gross of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune reported that “Cray has never said precisely why it wanted to acquire FPS,” but speculation was that Cray might have been interested in the specific type of microprocessors FPS used in its machines, which were the same as those used in Cray’s workstations.

In any event, FPS ceased to exist after the purchase and became an Oregon-based subsidiary of Cray that continued to produce machines for the business market. Four years later, in 1996, Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI) acquired Cray and shut down the Oregon unit. The Star-Tribune noted that SGI already made high-end business servers and viewed the former FPS product line as redundant.

Sequent Assimilated by Big Blue

Sequent Computer Systems lasted longer than the other companies discussed above, almost (but not quite) making it to the year 2000. It also got the latest start of the four companies. The company began under the name Sequel–later changed to Sequent–in 1983 when 17 Intel engineers led by Casey Powell left the company to form their own startup. At the time, the New York Times noted, the new company had “no clear notion of what it would make.”

Eventually, the group produced the Sequent Balance 8000 seen in this episode. The Balance was a 32-bit UNIX machine. After partnering with Oracle Corporation, Sequent enjoyed substantial success in the high-end UNIX market during the late 1980s and 1990s.

In July 1999, IBM purchased Sequent for $810 million in cash. Big Blue quickly assimilated Sequent into its existing server division, which by that time was moving from UNIX to Linux-based machines. By 2001, the Associated Press reported, “just about everybody and every symbol of Sequent [was] gone.” A number of former Sequent employees told the AP that IBM had “botched” the integration of their company leading to an “exodus of top talent and a steep decline in sales of Sequent’s hardware.”

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of March 11, 1986.

- Howard L. Resnikoff (1937 - 2018) enrolled as a student at MIT when he was just 16. After earning his doctorate in mathematics from Berkley in 1963, he worked in academia for the next two decades, holding faculty and administrative positions at MIT, Rice University, Harvard, and the University of California, Irvine. As noted in this episode, Resnikoff was also a co-founder of Thinking Machines Corporation. In 1986, he founded another company, Aware, Inc., where he also served as CEO. Resnikoff died in 2018 at the age of 80.

- Eugene Brooks remained with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory well into the 2010s. A 1990 New York Times profile noted that Brooks’ Hypercube design “was widely copied in the computer industry” during the late 1980s.

- P. Appleton Jones, who served as Elxsi’s president when this episode aired, later joined Kendall Square Research Corporation, a Massachusetts-based supercomputer company, as an executive vice president. Kendall Square collapsed in 1993 after the company’s auditors found executives were misreporting their sales figures. This led to a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) investigation. In 1996, Jones agreed to pay the SEC a $321,526 penalty–later reduced to $40,000–and was barred from serving as a senior officer of a public company for 10 years.

- David Rodgers remained with Sequent as a vice president until 1996. He then had a four-year stint at Compaq as vice president of business applications before bouncing around a number of web technology companies during the 2000s. His most recent position was a senior vice president with ShotSpotter Inc., which ended in 2019.

- H.T. Kung moved from Carnegie Mellon to Harvard in 1992. Kung remains at Harvard today as the William H. Gates Professor of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering. Kung’s WARP research led to a joint venture between CMU and Intel called iWarp, which built three parallel processing supercomputers between 1989 and 1992.

- Jeff Canin stayed with Hambrecht & Quist until 1989. He continued to work as a technology industry analyst until the mid-1990s when he moved into venture capital.

- Babble 123 was a real program that you can still run today thanks to the Internet Archive.

- The Zenith Z-170 was based on a design licensed from Morrow Designs, the company owned by Chronicles regular George Morrow. As it turned out, the IRS decision to award its contract to Zenith proved to be the final nail in the coffin of Morrow Designs. I’ll delve more into that story in an upcoming special post.