Computer Chronicles Revisited 56 — SHURLOC, OCIS, and Probe One

During this third season of Chronicles, there have already been several episodes dedicated to the impact of computers on specific vocations, including the media, politics, and medicine. (There was also an episode on the legal profession, which is among those still missing from the Internet Archive.) This next episode from January 1986 continues the trend, with a show discussing computers in law enforcement.

Giving Law Enforcement Rapid Access to Information

Stewart Cheifet delivered his introduction from an FBI office. There was a woman typing at a computer. Cheifet said she was a computer scientist for the FBI trying to solve a crime. He noted that law enforcement agencies around the country were now using computers to make police work more efficient and effective.

In the studio, Cheifet and Gary Kildall looked at Murder by the Dozen, a computer game for the Macintosh where the player had to solve crimes in a fictional city called Micropolis. (Cheifet mistakenly called it Metropolis.) Cheifet noted that in the game the player could use a “crime computer” to gather clues. He added that real police were now using real computers to catch real criminals.

Cheifet asked Kildall if this was yet another example of a “vertical application” of a computer’s ability to massage massive amounts of data. Kildall said it was a whole lot more because you were dealing not just with data but also graphical materials like fingerprints and photographs. No one person could deal with such things on 3-by-5 index cards or scraps of paper. So it was interesting to see how computer technology, data communications, and database systems were applied in this area where users needed to have rapid access to information.

California Attorney General Introduced Computerized Fingerprint System

Wendy Woods presented the first of three remote segments for this episode. She reported from the California Department of Justice in Sacramento, which had implemented a computerized fingerprint system called Cal-ID. Woods said that since Scotland Yard had started using fingerprints to track criminals in the 19th century, law enforcement agencies have faced the uncomfortable fact that a fingerprint without a suspect was often useless.

Woods explained that to match a smudged print taken from the scene of a crime to one of the millions on file was so time-consuming that a criminal was likely to die before an accurate match was made. To break this intricate code of loops and ridges that made a person unique, the California DOJ replaced its seven million fingerprint cards with optical discs and exchanged manual searches for a pattern search by computer (i.e., the Cal-ID system). Woods said the results had been rewarding.

At a previously recorded press conference, California Attorney General John Van De Kamp said that in a recent case involving the murder and kidnapping of two UCLA students, the only available fingerprint was very faint, having come from a car that was “torched” to destroy any clues. He said this was an example of a case that would never have been solved without Cal-ID. He explained that matching this particular print required searching three million records. He estimated it would have taken a fingerprint specialist 67 years to perform that search manually. Cal-ID performed it in less than 20 minutes.

Woods said that Cal-ID relied on a $20 million NEC supercomputer that could search 12 million digitized prints at a rate of 12,000 per second. As the prints came in they were scanned and electronically stored. Minutiae–the identification points of a fingerprint–were then mapped out according to the number of ridge lines between one point and its four closest neighbors. it was the relative position of each point to the others that the computer considered when looking for a match. Each print was given a score, indicating the probability of an exact match. But the final confirmation was still done by a human being.

Woods said the Cal-ID system would ultimately offer remote access so that local police departments could get immediate help from the world’s fastest–and most accurate–sleuth.

Computers Facilitated Expansion of 911 Service

Louise Anderson and Steve Port joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio for the first of two round tables. Anderson was the marketing coordinator for Command Data Systems in Dublin, California. Steve Port was a captain and operations commander with the Hawthorne Police Department in Los Angeles County.

Kildall opened by asking Port how computers had helped him as a police officer. Port said computers had helped greatly. His department started with computer-aided dispatch about 10 years ago. It had greatly simplified call-routing and finding what officers were available and responding to calls more efficiently.

Kildall asked about the use of computers with this 911 system he’d been hearing about. (The first 911 systems were deployed in the United States in the late 1960s, but even by the mid-1980s they were still not universally available.) Port said it had been great because when people called 911, the police could immediately find out what address they were calling from and dispatch officers right away.

Cheifet asked Anderson to explain how the 911 system worked with a Digital Equipment Corporation VAX computer. Anderson said that when a dispatcher received a 911 call, they would see the information associated with that telephone number on the bottom of their terminal display. If a caller gave a general description of their location, such as a supermarket, the computer could help the dispatcher narrow down the possible options, i.e., which supermarket. Kildall said the computer then effectively coordinated all of the dispatch information through a central computer system. Anderson said that was correct.

Kildall then asked Anderson to demonstrate another product made by Command Data Systems called SHURLOC. Anderson explained this was a crime analysis system. This system made it possible to conduct searches when you didn’t know a person’s name or a particular case number. Cheifet clarified this would be useful in a situation where a witness might give a general description of a suspect but not their identity. Anderson said that was correct.

Anderson performed a sample search in SHURLOC for a particular make and model of car, in this case a Chevy or Ford manufactured between 1960 and 1970. Kildall asked how big was the database. Anderson said this was a demo database so it didn’t have many records. But for a regular police department, you might have 300 to 400 people in a “known offender” file.

Anderson continued her demo. The software pulled up eight matches for the vehicle parameters entered. Anderson said that in a hypothetical criminal investigation, a detective could then try to match a suspect description with one of those eight vehicles, or at least narrow the list down.

Cheifet asked Port if this sort of system actually lead to a higher rate or arrests and convictions. Port said it was hard to say. But he added the real benefit was that any officer could perform this type of computer search, as opposed to going to one central focal point and asking someone else to perform a manual search. From that standpoint, the police were more productive because they could have a faster turnaround in accessing information.

San Jose Among First Cities to Equip Police with Mobile Computers

Wendy Woods presented her second remote segment, this time from the San Jose Police Department. Woods noted that for years, police departments kept track of units in the field through “the old card-on-a-peg” method. Today, more departments had computerized their dispatch services, and San Jose’s police department was among a handful who had taken computers one step further. All command officer squad cars were now equipped with mobile computer terminals that provided officers with access to the location and status of all units in the field, as well as motor vehicle and crime record information from state and national databases.

Sargent Aubrey Parrott of the San Jose Police Department told Woods that when the computer system went down temporarily you really felt lost. It was like being in a dark tunnel with no lights available. You ended up spending a lot of time listening to the radio and talking with the dispatcher to keep track of everyone.

Woods explained that San Jose police’s 48 mobile units accessed a separate radio frequency and interfaced with Santa Clara County’s giant digital minicomputers, which controlled the entire dispatch system via a single IBM PC. Woods said the system had performed flawlessly since it was installed six months ago.

Woods said that within the next few years, virtually all metropolitan police departments were expected to install similar mobile terminals in their own squad cars. Now that the terminals were smaller, they were less conspicuous.

Mapping Crime Statistics

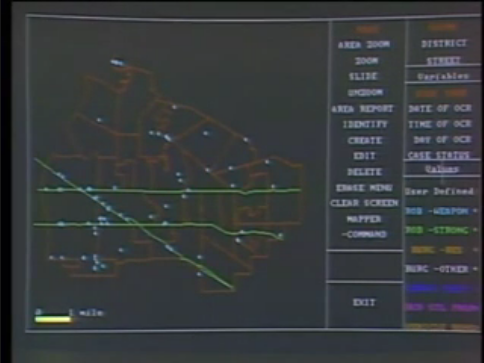

Back in the studio, Louise Anderson and Steve Port demonstrated another of her company’s systems. This one ran off a Compaq Portable. Port explained the system integrated a database with graphics software that could produce a map of the city. In the demo, the software extracted from the database all of the robberies that had occurred within the past 30 days and plotted those crimes on the map (see below).

Port said he could then take this visual information, go to his lieutenants and sergeants, and ask them to come up with a plan to deploy officers and deal with these crimes. Kildall said this database was kept up to date then. Port said yes, it was updated every day.

Cheifet asked if you could actually select a “dot” on the map and get more information about that particular crime. Port said yes, all you had to do was click and the software would pull up a separate screen with a full crime report. Kildall asked about other functions of the software. Port said you could zoom in on specific streets or districts.

Cheifet clarified that these systems were actually in use now and not just a demo model. Anderson said that was correct. In addition to the Hawthorne department, Anderson said her company installed a similar system for the Norwalk, California, police department, which was also located in Los Angeles County. Command Data Systems was also contracted to install systems in several other places.

FBI Official Credited Computers with Helping to Catch Assassin

Stewart Cheifet presented the third and final remote segment, this one from the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in Washington, DC. Cheifet said the FBI used a sophisticated collection of the latest computer hardware and software in catching criminals. Indeed, the FBI had invested over $500 million in computers. The agency had seven mainframes, many with coupled backups, located at the National Crime Information Center. Cheifet said the FBI’s systems could store up to 250 billion text characters, 17 million records, and more than 500,000 transactions per day. There were also 20,000 terminals that could access the system.

Cheifet said that computers had given the FBI investigative capabilities that it never could have had in the days of 3-by-5 index cards. He said that one example was a murder case involving a judge in Texas. William A. Bayse, the FBI’s assistant director, told Cheifet an alibi for one of the suspects was that he was in a different place. The FBI went through local hotel registrations looking for the suspect’s name or aliases. By using computer search, the FBI was able to determine the suspect was in San Antonio the night of the murder.

Cheifet said that one of the FBI’s top priorities was domestic terrorism. And with its new computer systems, FBI agents could access critical information in the field. Bayse said that for example, an agent could follow a van on Route 10 heading out of El Paso, Texas, with suspected terrorists. That agent could now access any FBI database from his car while driving and still maintain visual surveillance.

Cheifet said the FBI also used computer-generated behavior profiles. In a hostage crisis, the agency consulted with computers to predict terrorist behaviors and helped in developing a negotiating strategy. The computer was used not only to catch criminals after the crime had been committed but to prevent them in the first place. Bayse said the FBI Had a file sponsored by the United States Secret Service of threats to federal protectees such as the President of the United States. Bayse added that one hour after that system became active, there was a hit for someone on their way to Washington with a threat against the President. For the first time, Bayse said the Secret Service could track people who were not under arrest or detention but were still considered “legitimate” threats.

Cheifet said the FBI was most proud of its use of artificial intelligence, particularly its Organized Crime Information System (OCIS), an expert system engineered using knowledge from the agency’s top agents. The system applied rules to a massive database looking for “suspicious” conduct.

Using Expert Systems to Look for Serial Killers

For the final segment, Dr. Earlene Busch and David Hall joined Cheifet and Kildall. Busch was the founder and president of Information Access Systems in Boulder, Colorado. Hall was the director of information systems programs with Search Group, Inc., in Sacramento.

Kildall opened by asking Busch for a demonstration of her company’s software, known as Probe One. Busch said it was an “investigative information management system.” It was a professional support system for law enforcement. She quipped that Probe One could be viewed as the “Watson” to Command Data Systems’ SHURLOC.

Busch explained that Probe One enabled investigators to search for a criminal modus operandi using their own language. For example, a detective could ask the system to provide documents about homicides where the victim was assaulted and the body was found in a car. Busch said the system handled such a request like a document–that is, it determined the subject matter and searched a series of telex dispatches.

Kildall clarified that without this type a system, an investigator would have to review all this information manually. Busch said not only would the investigator have to read it, they would to find it first. In that sense, Probe One functioned as a very good research assistant.

In the demo search, Busch said there were 28 documents that were relevant to her request, which were ranked in relevance order. Cheifet asked for clarification about what “relevance” meant. Busch said in simple human terms, it was “like it in subject matter,” i.e. other murder cases where victims were found in cars.

Cheifet asked if a close match in terms of relevance meant that both crimes were committed by the same person. Busch said that was the general concept behind a modus operandi search–finding a pattern of criminal behavior that was repeated. (Busch then read some details from her sample match, which I won’t repeat here.)

Kildall wanted to know more about the technology behind Probe One. Did the program actually take apart or parse the sentence typed in by the user? Busch said no, the user told the system upfront the subject matter it would be handling. In this sample case, it was asked to handle “homicides.” The system could be adopted for other, non-criminal subjects, such as mining support or a legal library. Kildall asked how any placeholder words like “the” and “or” were treated. Busch said the system ignored them.

Kildall continued to press on how the matching process worked. Did the software pre-analyze all of the documents? Again, Busch said no, the program analyzed the subject matter and the terms that made distinctions between subject matters, such as between “victims” and “homicides.”

Cheifet noted that Probe One was being used by law enforcement in the State of Washington as part of its investigation into the Green River murders, a series of unsolved homicides believed to be the work of a serial killer. He asked Hall to what extent do police departments share these kinds of databases and information. Hall said databases like Probe One were very difficult to share. There was no system designed at the moment to transfer documents back-and-forth easily. So you had to know what you were looking for when you called another police department to ask for information from their database.

Kildall asked Hall if he saw that trend changing towards more integration. Hall said that he believed with the development of systems like Probe One, including the FBI’s OCIS, you would see greater sharing.

Cheifet asked how often these types of sophisticated systems were actually used. Was cost a major factor in determining whether a police department could get into this kind of computer support? Hall said definitely. It was a difficult process to secure funding from states and municipalities for these systems.

Kildall asked if there were any concerns about the potential for the abuse of databases that collected information about people related to crimes. Hall said it depended who had access to the information. The databases they were discussing here would only be open to law enforcement and criminal justice agencies. It would not be something out in the public.

Cheifet asked if the use of the Probe One in the Green River investigation was the first such time a system had been applied to an active investigation. Busch said yes. The other prior application was office automation. Cheifet asked what sort of feedback Busch had received from law enforcement in Washington. Busch said the officer managing the system in Washington was “quite enthusiastic.”

Kildall wanted to know how much decision-making was actually done by the program. Do the investigators actually go back and check to see if the cases are relevant? Busch said the judgment the computer made was simply in reference to the document base and relevancy to the request.

Would Police Computers Save Taxpayers Money in the Long Run?

George Morrow’s closing commentary focused on the ethical and fiscal implications of the use of computers by law enforcement. He said certain security features built into computer operating systems, such as system logs, could help keep abuse of information by law enforcement personnel to a minimum. But we also needed to realize that computers were a potentially productive tool for police departments. Criminals almost always repeated the way they committed a crime. And computers were particularly good at spotting and analyzing repetitive patterns. They also saved time and paperwork. Computers could ultimately make tax dollars work harder for taxpayers when it came to law enforcement.

New “Pixar” Computer Used to Create Special Effects for Sherlock Holmes Film

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in January 1986.

- IBM was expected to release several new products on January 21, 1986, including the “clamshell” laptop portable and TopView 1.1. Cheifet said the new version of TopView would reportedly add networking features and support for 3.5-inch disk drives. But it would not address the 640 KB memory limit of MS-DOS.

- Atari Corporation reportedly planned to release an upgrade of the 520ST called the 1040ST. The new machine would have over 1 MB of memory and integrate the power supply and disk drive into the main unit. Atari also announced a new version of the 520ST with an RF converter would start appearing on the shelves of retailers like K-Mart and Toys ‘R’ Us.

- Several major pieces of computer legislation remained pending at the start of the new congressional session.

- Epson and Toshiba announced the development of new color LCD screens for computers. Epson said its new 5-inch color LCD was 10 times brighter than existing black-and-white LCD screens and featured a resolution of 480-by-440 pixels.

- A California optometrist released a new $15 screen overlay template called the “EyeSaver” (see below) to help reduce eye strain by focusing a user’s eyes at the correct level.

- The developers of a new program called House Call promised to diagnose up to 400 medical problems. The program cost $40 and came on two double-sided floppy disks.

- The recently released film Young Sherlock Holmes included a special effect of a knight jumping out of a stained-glass window and waving a sword. Cheifet said the effect was produced using a new computer from Industrial Light & Magic, a division of LucasFilm. The computer was called “Pixar” and not only produced the image but electronically combined it via laser scanning with the existing film footage of an actor. The 38-second effect took the Pixar and six engineers nine months to create.

Busch Retired from Making Expert Systems to Create Organic Cuisine

Earlene Busch is a native of Colorado. According to a profile by Scott Noble for Saltscapes Magazine, she grew up on a wheat and cattle ranch. Busch, whose maiden name was Kingrey, enrolled at the University of Colorado in 1958. While on a family vacation in Mexico she met a United States Air Force pilot, Elwin Busch, and they married at the end of her freshman year, in June 1959. The couple had two daughters.

Elwin Busch, then a captain, died in combat in June 1967 when his plane was shot down during the Vietnam War. Sadly, Captain Busch’s brother, Lt. Roland Busch, Jr., had died six years earlier in 1961 when his Navy plane crashed in an accident off the coast of California. Lt. Busch had previously survived 17 months as a prisoner of war during the Korean War.

After her husband’s death, Earlene Busch returned to school in Colorado and completed her doctorate in communications in 1980. She founded Information Access Systems, Inc. (IAS), in May 1982. As discussed in the episode, Busch first came to public attention when her expert system was used as part of the investigation into the Green River serial killings in Washington. Lawrence E. Lewis, an officer with the Fullerton, California, police department, expanded upon IAS and Busch’s role in the case in a 1988 paper:

In January of 1984, the King County Washington Police Department formed the Green River Task Force to apprehend a serial killer wanted for the murder of at least 27 young women. The case involved more than 2,000 suspects and 300,000 pieces of evidence. The amount of information generated was immense, particularly as the number of victims increased to 42. A decision was made to try and locate a computer system that could handle this information in an intelligent way, that could be queried in natural language, and that could have the abilities of an expert system. A company called Information Access Systems (IAS) from Boulder, Colorado, was selected as it had developed an expert system that used natural language. The system was called Judgment Space (J-Space). At the time the system operated only on a specific type of minicomputer and cost approximately $200,000, not including the labor cost, for a year’s worth of data input.

Lewis said that J-Space did not actually solve the Green River murders but was “successful in organizing the information” and represented “a step for law enforcement in terms of using expert system technology.” (The Green River killer was arrested in 2001 due largely to DNA evidence and subsequently pleaded guilty to 48 counts of murder.) Lewis added that Busch had also sold a new expert system to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, which I believe was the Probe One that we saw in the Computer Chronicles demo.

Busch ran IAS as a private company for approximately 20 years. She changed the name of the company to Circa Logic, Inc., in 1998. Sometime around 2000, she sold the company’s expert system technology and retired the business as an active concern. (The company continued to exist on the Colorado books until 2010.)

It was around the turn of the century that Busch decided to embark on a new career as an innkeeper and chef. In 2000 Busch traveled to Cape Breton, an island that forms part of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, to pick up some maple furniture she had ordered from a local artisan. Busch decided she loved the area so much that she decided to build an inn on the island.

More than two decades later, Busch still owns and operates the Chanterelle Inn. She also decided to train as a chef so that she could run the inn’s restaurant, 100km, which serves locally grown organic food. Busch gave an interview last September to a local Cape Breton website where she discussed how her business was coping with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Cheers” Actor’s Father Was Contract Killer in 1979 Assassination

Stewart Cheifet’s interview with the FBI’s William Bayse mentioned a murder case involving a Texas judge but did not go into detail. So here’s the back story. On May 29, 1979. U.S. District Judge John H. Wood, Jr., was shot and killed near his home in San Antonio. Wood was the first federal judge to be killed in office since 1867.

Time magazine reported in 1982 that Judge Wood had been scheduled to preside over the trial of Jamiel Chagra, a reputed dealer in illegal narcotics. Given that Chagra faced a life sentence if convicted of drug trafficking–and Wood had a reputation for handing out maximum sentences–Chagra allegedly paid another man, Charles V. Harrelson, $250,000 to shoot and kill the judge. Harrelson had been convicted of an earlier contract killing in 1973 and paroled in 1978.

Harrelson claimed that he was 270 miles away in Dallas when Wood was killed in San Antonio. As Bayse mentioned to Cheifet, the FBI managed to shoot that alibi down using computer analysis. But the key evidence apparently came from Chagra’s brother, who agreed to testify against Harrelson and several other co-conspirators (except Jamiel) as part of a negotiated plea agreement. Harrelson was ultimately tried and convicted of Wood’s murder and received a life sentence. Jamiel Chagra was acquitted of the murder–at a trial presided over by future FBI director William S. Sessions–but convicted on other charges.

Coincidentally, when this Chronicles episode aired in early 1986, Harrelson’s son, actor Woody Harrelson, was in the middle of his first season on the NBC comedy series Cheers. Woody Harrelson told The Guardian in 2012 that while he’d been estranged from his father since childhood, he nevertheless “spent a couple of million” dollars in an unsuccessful effort to try and get him a new trial. Charles Harrelson died in prison in 2007.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and had an original broadcast date of January 14, 1986.

- William A. Bayse (1937 - 2004) worked as a research engineer for NASA and in several positions with the Department of the Army before joining the FBI in 1978. After leading the computerization of the FBI as an assistant director during the 1980s, Bayse was named the Bureau’s chief scientist in 1993, the first non-agent to hold that position. He retired the following year. Bayse died in 2004 after suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

- John Van De Kamp (1936 - 2017) served as Los Angeles County District Attorney from 1975 to 1981. In 1982, he was elected Attorney General of California and held that post until 1991. Van De Kamp unsuccessfully sought the Democratic Party’s nomination for governor of California in 1990, losing a primary election to Dianne Feinstein (who lost to Republican Pete Wilson in the general election). Van De Kamp later served as president of the California State Bar from 2004 to 2005. He died in March 2017 at the age of 81.

- Steve Port served more than 30 years with the Hawthorne Police Department in Los Angeles County. He became Hawthorne’s chief of police in 1989 and held that post until his retirement from the department in 2006. He later served as the interim chief of the El Camino College Police Department.

- Sargent Aubrey Parrott was a San Jose police officer for 57 years. According to a 2018 profile in the San Jose Mercury News, Parrott worked his last shift in October 2018, having spent 32 years as a full-time officer and another 25 as a reservist. It was believed that Parrott was the longest-serving police officer in San Jose history.

- There wasn’t much available information on Command Data Systems. The company was based in Dublin, California, and apparently formed around 1978. In June 1989, Denver-based US West, Inc., acquired Command Data Systems through one of its subsidiaries. US West was one of the “Baby Bells” and later merged into Qwest Communications International, which later merged into CenturyLink, which is now known as Lumen Technologies, Inc.

- Search Group, Inc., also known as SEARCH or the National Consortium for Justice Information and Statistics, is a nonprofit organization founded in 1969 to develop technologies related to criminal records. SEARCH is funded primarily by the federal and state governments.

- Murder by the Dozen, the program demoed during the studio introduction, was developed by New York City-based BrainBank, Inc., an early edutainment company, and first published by CBS Software in 1983.

- IBM did not release TopView 1.1 until June 1986.

- Just a couple of weeks after Stewart Cheifet mentioned the Pixar computer during “Random Access,” deposed Apple co-founder Steve Jobs would purchase the computer graphics division of LucasFilm and organize it as an independent company, Pixar, Inc.

- Depite the novelty of computer-generated effects, the movie Young Sherlock Holmes was a commercial flop in the United States, only grossing $18 million domestically. Roger Ebert, the longtime film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave the film a three-star review, noting of the stained-glass sequence, “The elaborate special effects [] seem a little out of place in a Sherlock Holmes movie, although I’m willing to forgive them because they were fun.” He quipped that Holmes should have ended the film by deducing the “eventual invention of computers.”