Computer Chronicles Revisited 54 — The Hardcard, Masterflight 60/60, Hyperdrive, and the Bernoulli Box

As we close out 1985 on Computer Chronicles, the discussion returned to a familiar subject–storage devices. This next episode looked at hard disk storage specifically. Keep in mind, hard disks were still not considered standard equipment at this time. The Macintosh, for example, did not come with a hard drive. And while you could purchase an IBM PC-AT with a 30 MB internal drive, many users still had to make an aftermarket purchase to acquire a hard disk, which could run over $1,000. Even at the lower end, you would still pay several hundred dollars for a device that stored a total of 60 MB.

Were Hard Drives Reliable?

Stewart Cheifet introduced the episode standing in front of an unidentified “mass storage device” from the old days–a 40-inch hard disk drive that held about 10 MB.

In the studio, Cheifet showed Gary Kildall two RAM cards–an AST Technolgies Six-Pack Plus (380 KB) and Intel’s Above Board (2 MB)–that were being marketed as mass storage alternatives to hard drives. Did that suggest there were still problems with hard disk drives? Kildall said the hard drive and the RAM card represented two different phenomena. The RAM card was an attempt to expand the limited amount of memory available in a 16-bit machine, a problem that would likely go away as the market shifted to 32-bit machines with “unconstrained” memory address space. With a hard disk, the issues had to do with the fact that it was a mechanical device subject to problems such as head crashes. So it was critical to backup data to protect against such crashes when they did occur.

Adding a Hard Disk with a Single Board

Wendy Woods presented the first of three remote segments. This first report looked at the Hardcard by Plus Development, a hard disk-on-a-card for the IBM PC and compatibles. Woods said that while hard disks were once limited to “mainframe monsters,” they were now a desirable addition for PC owners. Early disk platters had shrunk from 12 inches to 5 inches–and now to 3.5 inches in diameter. This made hard disks small enough to fit completely on a single PC board.

Stephen Berkley, the president of Plus Development, told Woods that the Hardcard was the first hard disk subsystem designed to be installed by the end-user. Up until now, he said disk drives were sold to the system manufacturers, who then performed a technical installation. With Hardcard, any user could install it in about 10 minutes. Berkley added the Hardcard was an “extremely reliable” product due to a lower parts count, as Plus Development designed both the mechanical and electronic components together.

Woods noted that sluggish sales of personal computers had led to business failures and pessimistic predictions. But vendors of add-on peripherals like the Hardcard saw the slowdown as an opportunity. Berkley said corporations in 1985 were not buying PCs in the quantities they used to, because they’d already bought millions of machines over the past three years. Now the focus was on improving the productivity of that earlier investment. In that respect, he saw the Hardcard as a natural purchase.

Woods said that paradoxically, as computer parts became smaller, users concurrently expected better performance and cheaper prices. But the trend toward smaller formats didn’t always exclude multiple standards. Berkley said there would be multiple standards as there had always been with traditional “Winchester” hard drives. For example, some manufacturers still use 14-inch or 8-inch media. The current 5.25-inch drives were now able to support 100 MB and 200 MB of storage. He expected similar increases in capacity over time from the more recent 3.5-inch hard drives. The next question was would there be a sub-three-inch disk.

When Would a Consumer Need 60 MB of Storage?

For the first round table, Alan Ebright and Joel Kamerman joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Ebright was a development manager with San Jose-based Prima Corporation, a hard disk drive manufacturer. Kamerman was CEO of Oregon-based Kamerman Labs, which produced an external disk drive called the Masterflight 6060.

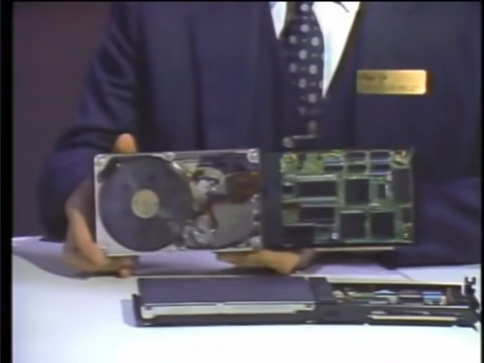

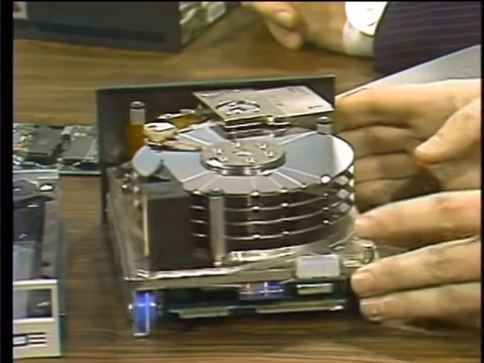

Kildall asked Ebright for a general explanation of hard disk technology. Ebright said that the IBM PC/XT currently shipped with a 10 MB hard drive as a standard. In the higher-performance PC-AT, the standard disk drive was 20 MB with an optional 30 MB disk. There were also add-in disks that could be placed inside the XT or AT. Ebright showed an example of such a disk produced by Priam, which was a 60 MB drive.

Ebright removed the cover to show the inside of the unit, which he explained a user should never do as it ruined the drive.

He explained the drive was an electro-mechanical device composed of four disk platters mounted on a hub turned by a motor. A read-write head then moved across the surface of the disk to access information. The arm was moved by a rotary voice coil motor. There was also a filter that pumped air into the head-disk assembly as it moved. This filter helped maintain a clean environment inside the disk.

Kildall clarified that the head did not not make contact with the disk platter, but instead floated on top of a cushion of air. Ebright said what actually happened was that as the disks were turned, they pulled air along with them in the cavity. This air was forced in between the head and the disk surface and built an air-bearing such that the head-to-disk difference was very closely controlled.

Cheifet noted that the main concern with hard disks was that they were considered “delicate, fragile things,” i.e., you couldn’t bang them and so forth. How delicate were the disks in practice? Ebright said hard disks were a precision, electro-mechanical instrument and they should be treated with care. But you would also treat your computer with care. You wouldn’t drop a CRT monitor, for example. As for Priam’s hard disk drive, it came with shock mounts that helped to minimize any impacts.

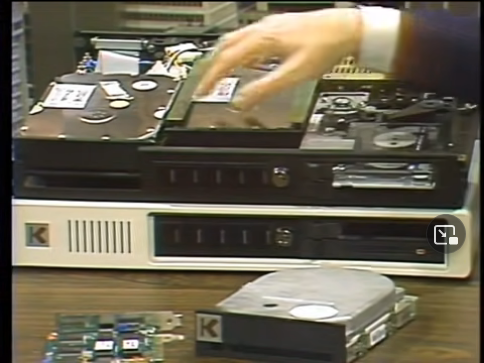

Kildall then turned to Kamerman, whose company made an add-on external hard disk drive. Kamerman said the unit he brought with him, the Masterflight 6060, contained two 30 MB hard drives and a 60 MB tape backup system. There was also built-in power direction to control access to other peripherals, and a lock and key to restrict access to the disk itself.

Kildall asked about the tape backup, specifically how long it took to make a copy of the hard disks. Kamerman said that it took about 2.5 minutes to backup 10 MB. Doing the math, Cheifet added that it would therefore take about 15 minutes to backup the entire 60 MB system, assuming the disks were full.

Kildall asked about the price difference between an external system like the Masterflight and an internal hard disk such as the Priam unit. Kamerman said prices ranged from about $399 for an internal system up to $6,000 for an external unit.

Cheifet asked Ebright what kind of user actually needed 60 MB of storage. When should a consumer think about needing that amount of storage? Ebright said the most common application for high-end, high-performance disk drives was was in high-end computers. So it was more likely that an AT user would use a 60 MB disk versus someone using an XT. Along with the added storage capacity, he said Priam’s hard disk offered better access times. You could get to the data quicker. And when you had more data, getting to it faster was generally a requirement.

Kildall said it was then a matter of better “seek times.” Ebright said such times were generally quoted over the capacity of the drive, so you had to look at the average access time based on the size of the drive. In other words, you couldn’t directly compare the seek times on a 10 MB and a 60 MB drive.

Cheifet returned to the issue of backup times, noting that even 15 minutes was a bit long. He asked if we were developing better backup technologies than “streamers” (i.e., tape drives). Ebright said streamers were still considered more cost-effective for large-capacity backup. He actually thought backing up 60 MB in 12 to 15 minutes was actually pretty good performance–especially if you compared it to backing up on floppy disk.

Apple Allowed Installation of Third-Party Hard Drive in Macs

Wendy Woods’ second report focused on the Hyperdrive, an internal hard disk add-on for the Macintosh. Woods said Mac owners were “raving” about the product. She said the Hyperdrive increased the Mac’s speed by a factor of three, added 10-20 MB of internal storage and enabled the machine to run multiple programs simultaneously.

Mark Wozniak, the brother of Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak and the general manager of the retailer Computer Plus, said the Hyperdrive was popular among his customers. They sold at least one Hyperdrive for every Mac sold. He said the Hyperdrive was a “fantastic” unit and he couldn’t imagine working on a Macintosh without one.

Woods then showed a demonstration of two Macintoshes running side-by-side, one with a Hyperdrive and one without. She said you couldn’t underestimate the importance of the Hyperdrive to the Macintosh–not only because it’s expanded the computer’s capabilities, but also because it helped the machine to gain acceptance in the business community, according to Kevin Curran, the president of General Computer Corporation, which produced the Hyperdrive.

Curran told Woods that Hyperdrive had gained acceptance within a number of Fortune 1000 companies. And major firms like Eastman Kodak, AT&T, and GE were now buying Macs with Hyperdrives to assess their potential as IBM PC replacements.

Woods said one of Hyperdrive’s biggest selling points came from Apple itself. The company said installation of a Hyperdrive by a technician–a process that took about an hour–would not void the Macintosh’s warranty. This was the first time that Apple had given a third-party vendor’s product that kind of endorsement. Woods said it was a testimony to the Hyperdrive’s success and utility.

Were Cartridge-Based Disks the Answer?

Wendy Woods’ third and final report took us back to the November 1985 COMDEX show for a demonstration of the Bernoulli Box, a hard drive alternative produced by Iomega Corporation. Woods explained the Bernoulli Box relied on magnetic storage disks in removable cartridges. Scott McVay, Iomega’s vice president of marketing, explained the Bernoulli Box used a 200-year-old principle developed by Swiss mathematician and physicist Daniel Bernoulli.

McVay said the Bernoulli Box worked with 10 MB and 20 MB removable cartridges. This allowed users to share mass databases among multiple sites within an office. He added that the cartridge used a flexible diskette but was very rugged. It could tolerate the abuse typical of most office environments. The cartridges could also be mailed across the country without any special protection.

Woods added that the Bernoulli Box featured an “unorthodox” read-write head meant to overcome the hard disk’s most disturbing quirk–the head crash. McVay said the Bernoulli Box was immune from such crashes because the device actually removed air from the disk media and the head to maintain contact. A traditional Winchester hard disk, in contrast, forced air into the drive to separate the head from the media. If the Bernoulli Box lost power, it lost the head-disk interface as well. The Bernoulli effect then caused the disk media to “fly away from” the head.

Woods said the potentially infinite capacity of a cartridge-based system was one answer to the expanding taste for more and more data storage, but it came at a price. The Bernoulli Box was approximately three times as expensive as a low-end hard disk. And storing files on multiple cartridges meant switching them back and forth like floppies.

Finally, Woods noted that optical discs could present a serious challenge, offering 50 times the storage of one 10 MB magnetic disk. As if to please everyone, she added, Iomega and Reference Technology, Inc., showed off a combined CD-ROM and magnetic storage system. McVay said the dynamics of data could be best managed by the Bernoulli cartridge. But the CD-ROM played into a different application, and the two brought together provided an amplified capability of what either could do separately.

When Would Hard Disks Come Down in Price?

Back in the studio, Robert E. Brown joined Cheifet and Kildall. Brown was the president of Landmark Software and the author of the book More Than You Ever Wanted to Know – about Hard Disks for the IBM PC. Alan Ebright also remained with the panel.

Kildall asked if hard drives were really taking over the minicomputer market. Brown said that was the way things were going. Kildall followed up, asking what kind of applications were being used with a hard disk. Brown said database applications required a tremendous amount of space. Program developers also had an “insatiable” appetite for disk space.

Kildall asked if a programmer really needed 60 MB of storage. Brown said it was much more convenient to have all the information you needed on one disk rather than switching floppy disks.

Kildall turned to Ebright and asked what consumer applications he saw for the hard disk. Ebright said you were able to do new things because of the new disks. You had more space available and you get to the data in that storage more rapidly. More specifically, he noted that system applications were migrating from large computers down into the personal computer environment. A person doing cash management, for instance, could have programs online at their desk to do analysis without going to a large mainframe or timesharing system. (Kildall added that these applications traditionally required something like a DEC VAX-11/750 minicomputer.) Ebright said that as hard disk storage made “super” microcomputers more powerful, the mainframes and minicomputers would have to step up as well to protect their share of the market.

Kildall asked if a home user would be interested in a 70 MB hard drive. Ebright said probably not. Brown added that anyone without that caliber of drive had some sort of business use.

Cheifet asked Brown where we were heading in terms of hard disk technology. Brown said there was really no limit. The rate of change depended a lot on IBM. When IBM was selling 10 MB drives on the XT, that was the standard size. Now that IBM was selling 20 MB and 30 MB drives with the AT, that was now the new standard.

Kildall asked about optical storage. How would that affect the hard disk market? Brown said that optical storage would become a wonderful backup medium in certain applications. But it was still a couple years away in coming down to a price that the typical business user would pay. And the performance of optical storage did not appear to be as good as today’s hard disk drives. Kildall suggested the optical disc could eventually replace tape streamers as a backup technology, and Brown agreed. Ebright added that an optical disc was also ideal for distributing large databases. And as users wanted to manipulate the data on a database, that would drive them towards purchasing larger internal hard drives where they could transfer that information from an optical disc.

Cheifet asked Ebright what could actually be done to add more storage capacity to a hard disk. Ebright said that in addition to adding more disk platters you could increase the track density, i.e., the number of tracks across the surface. You could also increase the number of bits around the surface and the efficiency of the encoding method.

Kildall said consumers were already concerned about the reliability of hard disks and now Ebright was talking about packing the data in even tighter. Should consumers be worried about more reliability problems in the future? Ebright said that higher-performance, higher-density drives would actually allow manufacturers to pack better technology into the units. Higher capacity would essentially force better design and quality.

Kildall asked how many hours an internal hard disk was expected to last on a typical AT machine. Ebright said 15,000 hours was the quoted specification for his company’s drives.

Finally, Cheifet asked Brown if the prices for hard disk drives would fall as they’d already done for floppy drives. Brown said prices had already come down tremendously. A year earlier (1984), a 10 MB drive sold for $1,000. Now, you could find 10 MB systems for as low as $395.

Appreciating Hard Disk Designers

George Morrow’s closing commentary noted that like freeways and money, disk space was a resource that tended be consumed as fast as it was created. The computer industry had come to expect that memory density would quadruple every two years–a whopping amount compared to money and freeways. For semiconductor manufacturers, this meant smaller geometries and larger, defect-free crystals. But for hard disk drive designers, it meant getting four times as much performance out of the “treacherous” world of magnetic flux. It meant even finer track densities and having to access those tracks with tricky electro-mechanical devices (and their associated problems). Morrow said it was important to appreciate the fantastic work of hard disk developers, whose work consumers had come to take for granted.

Apple Moved Ahead with Mac Plus as Japan’s “Fifth Generation” Stalled

Stewart Cheifet presented this week’s “Random Access,” which was recorded in December 1985.

- Apple planned to unveil an upgraded version of the Macintosh next month. The “Mac Plus” would feature 1 MB of memory, a double-density 800 KB disk drive, an expanded keyboard and greater speed. There would also be a SCSI interface to make it easier to connect third-party peripherals.

- IBM was reportedly planning to cut prices for the PC-AT by 20 percent due to excess inventory and softening demand.

- AT&T said it was starting to manufacture thin-screen plasma displays for portable computers. The AT&T display was one-inch thick and weighed four pounds. Cheifet said AT&T claimed its new display could be viewed under all lighting conditions and within a 150-degree viewing range.

- Digital Equipment Corporation announced its newest, fastest, and most expensive 32-bit “supermini,” the VAX 8650. DEC said the machine could run 6 million instructions per second and cost $500,000.

- Workers at Hewlett-Packard factories in California and Oregon were headed back to full-time work after months of reduced work schedules. But those same workers would also receive a 5 percent wage cut.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Golden Oldies (Software Country, $35), a compilation of four “classic” computer games: Pong, ELIZA, Conway’s Game of Life, and Colossal Cave Adventure.

- A U.S. Senate subcommittee heard conflicting testimony from computer scientists about the Reagan administration’s “Star Wars” defense program. Scientists from the University of Southern California and Bell Labs told the subcommittee that the technology already existed to support the program. But other scientists said the necessary software could never be debugged, since it could never be tested under real battle conditions. One expert also cautioned that the U.S. would be extremely vulnerable to espionage with respect to the software code.

- A Japanese report on the Fifth Generation computer project said progress was slow and the research might not bear fruit until the late 1990s.

- British scientists said they were making progress on their own fifth-generation project using what they called a “functional logic language” and “transputers.” The British said they would have a machine up and running by 1988.

- The world’s first ballet for humans and robots took place in Palo Alto, California. The original ballet called “Invisible Cities” featured nine dancers and a robot developed at Stanford. The choreographer said the robot performed “perfectly.”

Iomega Riding High in ‘85

Perhaps the two most recognizable companies from this episode were Iomega and General Computer Corporation. Iomega is less remembered today for the Bernoulli Box than its later cartridge-based storage medium, the Zip disk, which the company introduced in late 1994. Meanwhile, General Computer Corporation famously started out in video games and later evolved into a printer company.

Iomega started in 1980. Its three founders–David G. Norton, David L. Bailey, and Roderick J. Linton–were ex-IBM engineers who went out and got themselves some venture capital funding to start a data storage company. Although the founders were originally based in Tuscon, Arizona, they quickly relocated Iomega to Utah, where the company remained until moving to San Diego in 2001.

Heading into 1985, Iomega was on an upward trajectory. A July 1985 report from Associated Press writer Bob Kuesterman said Iomega reported a $2.52 million profit in 1984. That may not sound like much but it was a significant improvement after suffering $20 million in losses the previous year.

By this point the original founders had largely been pushed out in favor of new management. Gabriel P. Fusco, who took over from Bailey as president, decided to shift Iomega’s focus from marketing to computer manufacturers and towards direct-to-customer sales. The Bernoulli Box was meant to fill a gap left by IBM and the clone-makers, as these manufacturers did not offer a “high-capacity removable disk,” Kuesterman noted in his report.

Even at an initial retail price of $2,700, the Bernoulli Box proved successful within a certain niche of customers. Iomega reported $5.1 million in profits for 1985 and record sales of $126 million during 1986. Things would head downward after that, but I’ll get to that some other time.

GCC’s Post-Video Game Crash Transition to Mac Peripherals

General Computer Corporation (GCC) started in 1981. As I mentioned, GCC’s early claim to fame came in video games. The company’s founders were (mostly) a bunch of MIT dropouts, including CEO Kevin Curran, who developed modified versions of then-popular arcade games such as Atari’s Missile Command and Namco’s Pac-Man. The former prompted a lawsuit from Atari, then still owned by Warner Communications, over alleged copyright and trademark infringement.

Atari ultimately decided to abandon the lawsuit and offered the GCC folks a payoff to simply go away. According to an oral history prepared by Benj Edwards in 2017, the deal called for Atari to pay GCC $50,000 per month for a period of two years. On paper, this was supposed to be a contract for GCC to develop games for Atari. But in practice, one of the GCC founders told Edwards that Atari “just wanted us to go sit on the beach, or go back to school, and never wanted to see us again.”

GCC, however, decided to actually develop games for Atari. In fact, Edwards noted GCC would “would go on to design several arcade games and an entire new home console (the 7800) for Atari over the next several years.” I referenced the latter a couple of episodes back, as the 7800’s release was delayed when Warner Communications and the new Atari Corporation under Jack Tramiel got into a pissing match over who would pay GCC for its work.

But GCC’s most remembered contribution to the gaming world was its modification of Pac-Man, which eventually became Ms. Pac-Man. Atari said it was okay for GCC to sell its “conversion kit” for Pac-Man, provided it got permission from Midway, which was Namco’s U.S. distributor. After Kevin Curran and his colleagues presented their modification–which was developed under the name Crazy Otto–Namco not only blessed the project but decided to make it the official sequel to the original Pac-Man.

The video game market, of course, took a major nosedive in the mid-1980s. The collapse of Atari, Inc., in 1984 brought down the home console market. The arcade market also sustained its own separate downturn during this period.

Curran apparently saw the writing on the wall and by 1984 had decided to pivot GCC into designing peripherals for the newest hot tech product, Apple’s Macintosh. In addition to the HyperDrive, GCC also developed the Personal Laser Printer for the Macintosh. This helped re-launch General Computer Corporation–renamed GCC Technologies, Inc. in 1990–as a laser printer manufacturer. This would basically remain GCC’s main product line until June 2015, when Curran decided to dissolve the company.

Berkley Took Quantum Leap Following Bushnell’s Suggestion

Stephen Berkley’s Plus Development was actually a subsidiary of Quantum Corporation, which started in 1980. It turned out that a chance discussion between Quantum’s president, James Patterson, and our old friend, Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell, indirectly spurred the creation of Plus Development and its Hardcard. According to an August 1985 column by C.W. Miranker for the San Francisco Examiner:

One June night at a dinner in San Francisco, Bushnell “metioned that if he had low-cost disk-drives on a board he could use thousands,” Patterson said. “That got me thinking… We (at Quantum) spent months talking about it.”

“But with the day-to-day pressures, there was no clear way to get the project going. It became clear, if we were ever going to do anything about it, we would have to set a group of people aside.”

In October 1983, Quantum created a majority-owned subsidiary, rented a separate office and gave a handful of people three months to map out a business plan.

This subsidiary–Plus Development–was initially funded with $15 million and released the first Hardcard in October 1985. Although many imitators soon flooded the market with similar hard disks-on-a-card, Plus continued to produce variations of its own product up until 1992.

The Hardcard proved so successful that when parent company Quantum struggled in 1986 with its own 3.5-inch disk drive business, the board decided to replace Patterson with Berkley. Berkley served as CEO until 1992 and remained chairman until 2003. In 1993, Quantum absorbed Plus Development, at which point the latter ceased to exist as an independent company.

Another guest from this episode, Joel Kamerman of Kamerman Labs, would also cross paths with Berkley’s Quantum a bit down the road. In 1987, Kamerman started a new company, LaCie, to manufacture high-end external hard drives for the Macintosh line. Plus Development purchased LaCie in December 1990 for $3.8 million in cash. Kamerman continued to run LaCie as a Plus Development (and later Quantum) subsidiary through the mid-1990s.

Quantum Corporation still exists today although it now focuses on the storage systems business. Quantum sold its hard drive division to Maxtor in January 2002 in a stock swap valued at roughly $1 billion. LaCie was not part of that deal, as Quantum had already sold it back in 1995 to a French company, électronique d2, which then adopted the LaCie name. Seagate Technology acquired this new LaCie in 2012 for $186 million.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of December 17, 1985.

- Priam Corporation, which was founded in 1978, had started 1985 by acquiring another hard disk manufacturer, Vertex Peripherals. The combined company continued on for another four years. In 1989, Priam filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, having not turned a profit since 1984. The following year, Priam executives tried to relaunch the business under the name Priam Systems Corporation. But in 1991, the not-at-all-confusingly named Prima International acquired Priam’s remaining storage products line. As for Alan Ebright, he went on to have a long career in storage systems, working as a vice president at Maxtor in the late 1990s and early 2000s before becoming a consultant.

- Mark Wozniak continued to run Computer Plus until 1991. He later worked for Sony Computer Entertainment, the early Internet search engine AltaVista, and Acer America Corporation. His most recent position with Merchant e-Solutions ended in 2016.

- Scott McVay remained with Iomega until 1987.

- The Iomega/Reference Technology Bernoulli Box/CD-ROM hybrid was called the CLASIX DataDrive Plus. I could not find any evidence that this product ever made it to market.

- Apple did introduce the Macintosh Plus on January 16, 1986, for a retail price of $2,600.

- I actually knew GCC’s Kevin Curran. Our paths crossed on a professional project back in the early 2000s. Nice guy.