Computer Chronicles Revisited 53 — Reader Rabbit, Science Toolkit, A.G. Bear, and the Melard Access

This next Computer Chronicles episode launched the annual tradition of presenting a “buyers guide” for the holiday season. (It’s referred to as a “Christmas Buyer’s Guide” for this first installment.) These episodes would air each December for the duration of the series and typically featured panels composed of regular contributors.

Indeed, this first buyers guide had no in-studio guests aside from the three regular contributors from this third season: George Morrow, Paul Schindler, and Wendy Woods (who made her first on-set appearance). Woods presented one remote segment, but otherwise this episode simply had the hosts and contributors recommend technology-themed gifts to the viewers.

Would Christmas 1985 End the Computer Sales Slump?

Stewart Cheifet presented a brief cold open from a local computer store in San Mateo. This was followed with the customary studio introduction, where Cheifet and Gary Kildall looked at Jingle Disk, a Christmas-themed program released by ThoughtWare and running on an Apple IIe. Cheifet described it as the “ultimate hi-tech Christmas present for the hacker on your list.”

Wendy Woods then presented her remote segment for the episode, narrating B-roll footage of a local shopping mall in San Mateo that was bustling with holiday shoppers, many of whom were looking to buy computers. Don Endy, a sales representative at the local Radio Shack store, told Woods that computers were selling well this year. He attributed the increase to price cuts for the top-of-the-line machines, which had taken away a little from the sales of less-expensive machines.

Woods said that while the range of affordable machines had expanded, different features appealed to different types of customers. For instance, a child was more interested in color graphics than a spreadsheet. So Christmas sales of low-end computers were brisk. But as the gap narrowed between home and office machines, all shoppers were getting smarter.

Jim DeWhitt, an assistant manager at a store called Computer Craft, said that customers had become more knowledgeable, which was helpful. They seemed to know what they wanted and had friends who owned computers and could given them advice.

Woods noted that computer sales were disappointing overall in 1985 and many computer stores had closed for good. But retailers were optimistic that computers would continue to excite the public. DeWhitt said he expected the holiday season to be the strongest part of the year in terms of sales. He wasn’t deterred by the past year as far as any “slump” was concerned.

Using Your Apple II for Science!

George Morrow and Paul Schindler joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first round table. Given the departure from the usual episode format, I won’t attempt a straight recap. Instead, I’ll briefly run down the various products recommended by the panel.

- Cheifet opened by showing a program called All About Hanukkah published by Davka Corp. This was basically the Jewish holiday counterpart of the Jingle Disk seen earlier.

- Kildall recommended two computer books that he’d purchased for his own children: Kids and the Commodore 64 by Edward H. Carlson and Becoming a Mac Artist by Vahé Guzelimian. Both books were published by Compute!, a well-known computer magazine of the time.

- Morrow recommended Signal from Lotus. This was a real-time stock quotation system offered by the makers of Lotus 1-2-3 and used a combination of software and an FM radio receiver to receive information as opposed to a modem. (Below is a newspaper ad that ran for Signal around this time.)

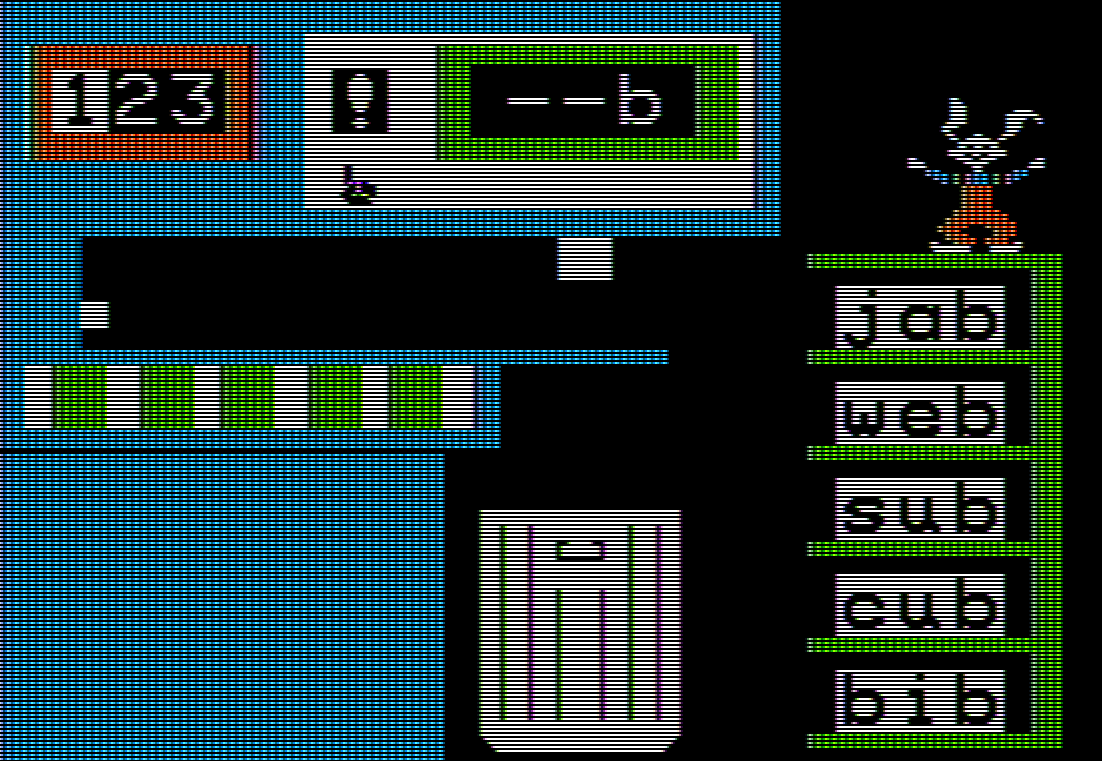

Schindler recommended a number of products that he’d previously reviewed for “Random Access,” including Ultimate Trivia, Bakup, and Higgins. He also gushed about XyWrite, a word processor published by XyQuest that he used in his own work. Schindler and Kildall then demonstrated Reader Rabbit, an educational software title published by The Learning Company, on an Apple IIe.

Reader Rabbit consisted of several mini-games designed to help young children learn how to read basic words. (I’ve recreated the demonstration below using an emulator.) In this mini-game, the child had to identify words that included a matching letter. The child–or in the on-air demo, Kildall–pressed the spacebar to let a word through if they thought it matched. Otherwise the word would “fall” into a garbage can at the bottom of the screen. If the child matched five words correctly, a dancing rabbit appeared.

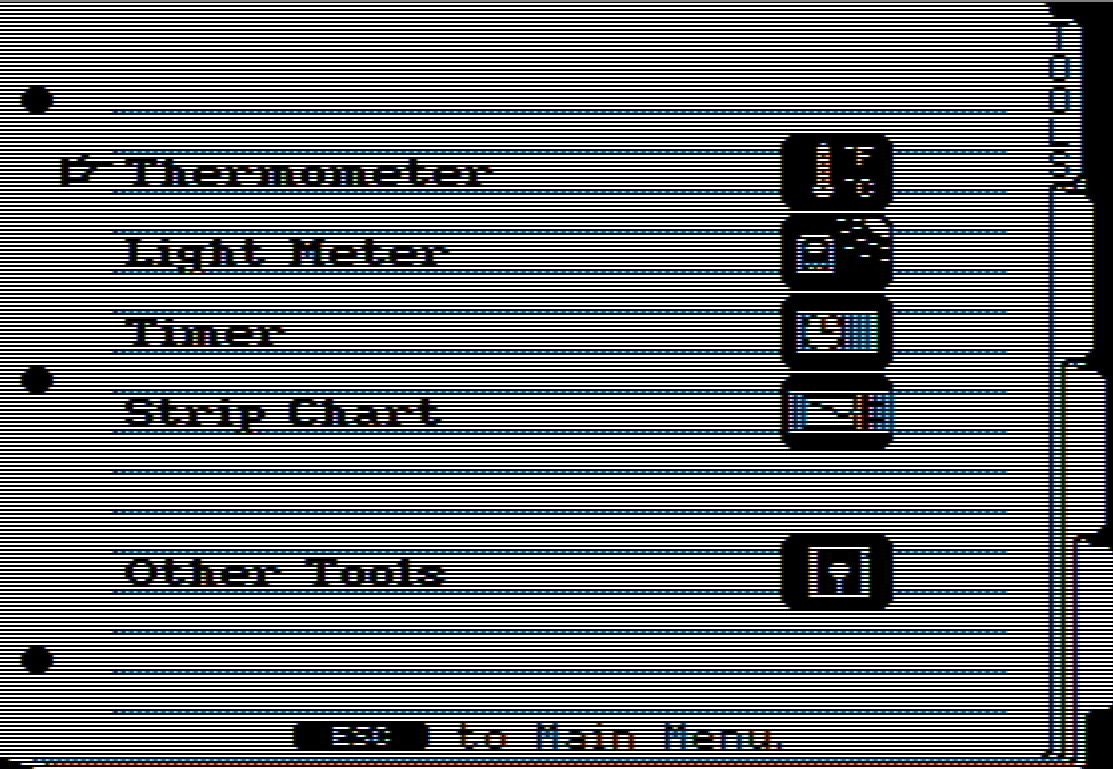

Cheifet closed the segment with another demo, this one for Science Toolkit by Brøderbund. This was a hardware-and-software package that enabled children to conduct basic science experiments using an Apple II. The Toolkit came with a photo-electric sensor and a thermometer that plugged into the Apple’s joystick port. The software received measurements from these probes and presented real-time graphs. There was also a built-in stopwatch function to time experiments. (Again, I’ve recreated the main menu from software via emulation below, although obviously I couldn’t access the hardware.)

Robotic Pets and a New Handheld Computer

Wendy Woods joined Cheifet, Kildall, and Morrow for the final segment. Woods brought with her two items produced by Axlon, a company started by Nolan Bushnell, the co-founder and former CEO of the original Atari, Inc.

The first item was A.G. Bear, a teddy bear with a voice-synthesis chip. The bear didn’t “talk” so much as make gibberish sounds in response to human speech. And in fact, Woods had difficulty getting the bear she brought to stop making noise, as it could be heard throughout the rest of the segment.

The rest of the group presented their hardware recommendations for the season. Morrow endorsed the Epson Equity line of IBM PC compatibles. Kildall suggested buying a “lightweight” printer such as the Okidata 192.

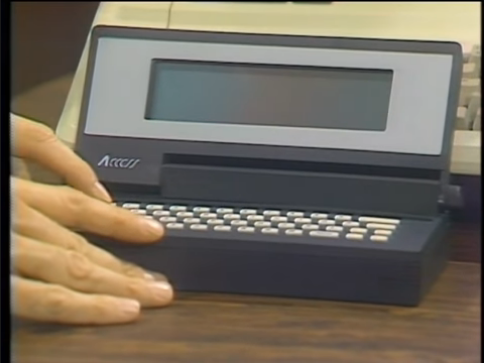

Cheifet endorsed a “delightful little machine” called the Access from Melard Technologies. This was a small handheld computer with a 40-column, 8-row LCD screen. Cheifet said it was capable of creating 80-column documents using a built-in word processor. It also had a file search utility. Kildall asked if the Access could communicate with other machines. Cheifet said it had a modem port and an acoustic coupler, so you could use it with a pay telephone. Morrow noted the screen had excellent contrast. Cheifet added the Access came with removable cartridges that could be used for either RAM or ROM and the battery lasted about 10 hours.

Woods concluded the program by showing off her second Axlon toy, a pair of Petsters, which were simple robots that looked like cats. Like A.G. Bear, the Petsters responded to human speech or clapping. They made a “meow” sound and started moving around the table. (Cheifet jokingly asked if the two Petsters could mate.)

Abandoned Adam a Surprise Holiday Seller

Stewart Cheifet presented this episode’s “Random Access,” which featured news stories from December 1985.

- December computer sales were looking good, not because of Christmas, but thanks to businesses motivated by year-end tax considerations. Home computer sales were projected to be down from 1984, while office computer sales would be up more than 30 percent.

- Cheifet said the “surprise hit” of the holiday season was the now-orphaned Coleco Adam, which was selling better than last year thanks to discounts.

- Microsoft was rumored to be coming out with a “generic” version of DOS 5.0, while IBM would have its own “superset” of DOS 5.0 that would take advantage of the PC-AT’s 80286 microprocessor while maintaining compatibility with existing DOS software. Cheifet said the main features of the new DOS would include better graphics, addressing more than 640 KB of memory, multitasking, and connectivity with mainframes.

- Steve Wozniak was buying up Apple stock following the departure of Steve Jobs from the company. Wozniak reportedly bought $5 million in Apple shares and planned to purchase more in the future.

- Data General said it had a new “lap portable” computer that would include a built-in hard disk drive and an easy-to-read screen. Cheifet said the product was described as a “laptop XT.”

- The Chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Operations said the Social Security Administration’s new computer system was a “mess,” suffering from missed deadlines, cost overruns, and political problems. Cheifet said the new computers were now expected to cost nearly $1 billion, almost double the original estimate, and two former SSA officials had been found guilty of soliciting bribes in connection with software contracts.

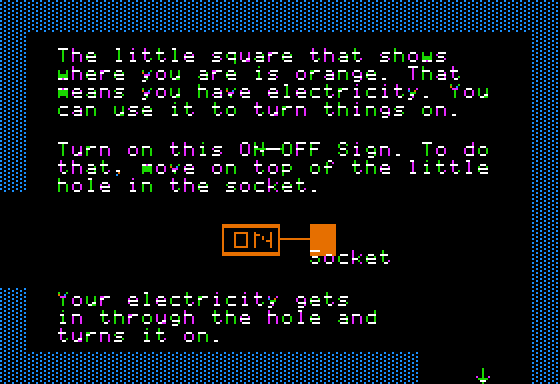

- Paul Schindler reviewed Rocky’s Boots, an educational game from The Learning Company ($50) that taught kids about electrical circuits.

- Reference Technology was selling a CD-ROM for the IBM PC with over 8,000 free programs–but you had to buy a $1,600 optical drive to run it.

- Borland International was reportedly buying up the electronic publishing rights to a variety of reference works, including Barlett’s, the Columbia Encyclopedia, and Black’s Law Dictionary.

- TW Technologies was now offering an $800 hard disk drive for the IBM PCjr.

- A new program called Chuckle Pops (Enlightened Software, $14.95) stored hundreds of jokes in a computer.

- Referencing an item I discussed in my last blog post, Atari Chairman Jack Tramiel profited at the recent Winter COMDEX show by subletting the company’s booth to 45 software vendors who paid $1,000 each for the privilege.

Nolan Bushnell’s Animatronic Fixation

Axlon was not the only company peddling technology-enhanced animal toys in 1985. According to a November 1985 report by Suzanne Dolezal of Knight-Ridder Newspapers, there were at least seven “animated” toys on the market that holiday season. In addition to A.G. Bear and the Petsters, there was Teddy Ruxpin and Gabby Bear, which both used a combination of animation and audio cassette playback; the Tattle Talk Monkey, which used a speech synthesis chip that could echo back a few words; and Chatter Animals, which produced “jungle-type sounds.”

As mentioned in the episode, Axlon was started by Nolan Bushnell, best-known as the co-founder of the original Atari, Inc., not to be confused with Jack Tramiel’s new Atari Corporation. Bushnell had long been interested in mechanical puppetry (i.e., animatronics). While a college student in the 1960s, he said he wanted to work for the Walt Disney Company as an “imagineer,” one of the people who designed the company’s theme park attractions, which often included animatronic figures.

Later at Atari, Bushnell started a restaurant called Pizza Time Theatre–better known as Chuck E. Cheese’s–which combined a pizza parlor and video arcade with an animatronic musical show reminiscent of a Disney attraction. Warner Communications sold the rights to the restaurant concept back to Bushnell after it fired him from Atari in 1978. Bushnell would take Pizza Time Theatre public in 1981, but the company filed for bankruptcy in 1984. A rival chain, Showbiz Pizza Place, then bought Chuck E. Cheese’s and the two companies merged its operations. (The combined company continues to operate restaurants today under the Chuck E. Cheese’s name.)

While Chuck E. Cheese’s was in the midst of its meteoric rise and fall, Bushnell also started a venture-capital group called Catalyst Technologies in 1981. Catalyst basically served as an “incubator” for tech startups, according to a 2017 article by Benj Edwards for Fast Company. Edwards said that at its height, Catalyst was home to as many as 20 different companies.

Axlon was one of those companies. Edwards said it was also “one of Bushnell’s favorites.” By 1986, Bushnell had “consolidated his business interests and personal attention” with Axlon and abandoned Catalyst Technologies altogether.

Axlon’s toys, including A.G. Bear and the Petsters, were distributed by the toy giant Hasbro, Inc. Indeed, one former Axlon employee told Polygon’s Jeremy Parish in 2018 that Axlon was “really a Hasbro division.”

Outside of A.G. Bear and the Petsters, Axlon’s only other notable toy was, quite literally, a noxious product known as Breath Blasters. According to a 1989 retrospective in the Boston Globe:

In 1987, Axlon Inc., a Silicon Valley company headed by Nolan Bushnell, founder of video pioneer Atari Inc., spent $70,000 developing Breath Blasters, dolls which when squeezed emitted odors reminiscent of vomit and other organic odors.

By that Christmas, “everywhere that it got on the shelf it sold out in minutes,” Bushnell boasts. “The problem was, several retailers decided they wouldn’t sell it. When you’d first open the box, this bad smell would come out. They decided that someone would think a kid had thrown up on the box, or something.”

Axlon later tried to pivot back to Bushnell’s old stomping ground, video games. In the early 1990s, Axlon developed two of the final games published by Atari Corporation for the original Atari 2600 console. Axlon also developed a never-released console called the NEMO for Hasbro, which was discussed at length in the previously mentioned Polygon article.

The details of Axlon’s demise are somewhat murky. In a 1992 article for the Tampa Tribune, Bonnie Lamp Fowler said Axlon stopped making Petsters in 1987 and distributed its remaining stock to a San Jose-based company called Alltronics. Axlon’s corporate filings with the State of Claifornia stopped in 1996. Benj Edwards and other sources have said that Axlon went public before being acquired by Hasbro. My guess is that Hasbro actually acquired whatever Axlon assets remained when Bushnell lost interest and decided to close up shop.

Ex-Atari Programmer Turned Adventure Into Edutainment

Another company featured prominently in this episode, The Learning Company, can also partially trace its lineage back to Atari, Inc. Rocky’s Boots, the program reviewed by Paul Schindler in “Random Access,” was designed by Warren Robinett, a former Atari programmer who developed three cartridges for the Atari 2600.

The most notable of Robinett’s three Atari projects was Adventure, a loose graphical adaptation of the text-based game Colossal Cave Adventure that was popular on 1970s minicomputers. In Adventure, players controlled a square avatar that picked up objects and used them to complete tasks in a multi-screen game world. Robinett adopted this same model for Rocky’s Boots, only instead of slaying dragons and unlocking castles, the player’s goal was to construct electrical circuits and build machines. Robinett later said in an interview that Rocky’s Boots “was originally intended to be an adventure game where you built machines to defeat the monsters,” but the concept later “evolved in a different direction.”

That different direction took Robinett from leaving Atari to joining Ann McCormick, a former nun and school teacher, and Teri Perl, a Stanford-trained Ph.D and educational psychologist, in forming Alternative Learning Technologies (ALT). Robinett started working on his revised concept for Rocky’s Boots with ALT. When the game was finally released in 1982, ALT had changed its name to The Learning Company.

According to a 2018 profile of The Learning Company by Abigail Cain for The Outline, during the development of Rocky’s Boots, McCormick hired another Stanford Ph.D, Leslie Grimm, to help Robinett part-time with the program. After joining The Learning Company full-time 1981, Grimm developed Reader Rabbit. Cain said the two programs put The Learning Company on the map:

Inspired by the methods of a “particularly fine teacher” in a nearby school district who taught students with language disabilities, [Grimm] created a dancing digital rabbit to guide children on their way to literacy. Reader Rabbit was born, published in 1984 as one of the very first character-based software programs. It spawned more than 30 spin-offs, which together sold at least 14 million copies.

Paired with Rocky’s Boots, TLC had both a critical darling and a popular franchise. “It’s not on people’s wish list to get something that teaches their second grader logic gates,” explained McCormick. “It’s on their wish list that they learn to read. So Reader Rabbit was a much more popular product.”

Perl, Grimm, and Robinett were also credited as the co-authors of Gertrude’s Secrets, an educational puzzle game in the same style as Rocky’s Boots. (Secrets was discussed in a previous Chronicles episode.) But as was often the case with 1980s software companies, The Learning Company took venture capital and its founders ended up leaving one-by-one in short order. Cain said that Robinett and Grimm were gone by 1985, Perl was fired, and McCormick was “pushed out” right around the time this Chronicles episode aired in December 1985.

Brøderbund Focused on Add-Ins and Add-Ons

I reviewed the early history of Brøderbund back in Part 41, where the main episode featured the company’s Dazzle Draw. According to Lauren Elliott, the lead designer on Science Toolkit, the “inspiration” for that project came from Brøderbund boss Doug Carlston, who wanted to “create a hardware extension for the Apple, the kind of package that lets you conduct real-time experiments rather than on-screen simulations.”

Science Toolkit also came at a time when Brøderbund liked to package its software with various physical add-ins. Most notably, there was Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, which came bundled with a copy of the World Almanac. Kate Willaert, a video game historian who probably knows more about Brøderbund than anyone, suggested to me this could have been a form of copy protection, as you couldn’t effectively use the software without the add-ins.

Another Brøderbund trend from this period was selling separate add-on content for its existing software–what we would now call an “expansion pack” or DLC. The Print Shop was perhaps Brøderbund’s most famous example of this, as you could buy a host of graphics libraries that provided additional clip art for the base program. Brøderbund sold at least three add-on modules for Science Toolkit. One of them was an “Earthquake Lab,” which included a seismograph and plotter to measure wave movements in the ground.

Unlike other popular Brøderbund programs such as Carmen Sandiego and Print Shop, Science Toolkit was an Apple II exclusive. The original program–formally known as The Science Toolkit Master Module–retailed for $70, with the add-on modules priced at $40 each. Brøderbund also offered a special “School Edition” of the base program for an additional $20. In a December 2021 social media post, Willaert noted that Science Toolkit was a “mid-tier seller” for the company. It actually performed better in its first couple of months after release than even Carmen Sandiego, although the latter would eventually sell more than four times as many units and enjoy a much longer shelf life (not to mention multiple best-selling sequels).

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of December 10, 1985.

- Melard Technologies, the New York-based company behind the Access handheld computer, was founded by Ali Sharif-Enami in 1982. During its 20-year history, Melard produced a variety of wireless computing devices, primarily for business and enterprise customers.

- A.G. Bear was designed by Ron Milner, who previously worked for Nolan Busnhell at Atari, Inc. (Milner had co-designed the Atari 2600.) Milner’s Applied Design Labs later acquired the rights to manufacture and sell a limited number of new A.G. Bears and replacement parts.

- The Coleco Adam originally retailed for $750 when it launched in 1983. According to newspaper advertisements I found from December 1985, retailers had slashed the price to just under $300. And that was for a computer with a printer! (The printer was not optional; it contained the Adam’s power supply.)

- I think Stewart misspoke when he talked about the rumors surrounding “DOS 5.0.” In 1985 the current version of DOS was 3.1. There would not be a MS-DOS 5.0 release until 1991.

- Data General did release its successor to the Data General/One–confusingly named the Data General/One Model 2–in May 1986. It did offer a built-in 10 MB hard drive, but it would set you back $4,635, according to InfoWorld. The base model with a single floppy drive only cost about $1,800.

- The ultimate fates of both The Learning Company and Brøderbund will converge in the 1990s, but I’ll get to that later. If you can’t wait, Abigail Cain’s article provided an excellent overview of that part of the story.