Computer Chronicles Revisited 51 — Grolier's KnowledgeDisc, InfoTrac, DEC Uni-File, and ISIDOS

Gary Kildall was not just the co-host of Computer Chronicles. He also co-founded and ran two software companies, Digital Research and KnowledgeSet (originally Activenture). As a software guy, Kildall was naturally interested in the newest means of distributing programs. Back in the first season of Chronicles, Kildall touted the potential of two possible magnetic disk replacements–the Capacitance Electronic Disc and bubble memory–neither of which panned out in the market.

But the third time was a charm, right? At least that was Kildall’s hope when he started Activenture to develop CD-ROM technology. The CD-ROM had also been featured on Chronicles before, when a Sony representative suggested we would see compact discs in computers by the end of 1985. Kildall certainly believed that would happen. Indeed, at the 1985 Summer Consumer Electronics Show, Activenture demonstrated its first CD-ROM product–an electronic version of the Grolier’s Encyclopedia–running off a CD player connected to an Atari 520 ST.

Now, I’ll talk more about Atari’s role in all this after the episode recap, but suffice to say Jack Tramiel’s company never actually shipped a computer with a CD-ROM drive to consumers in 1985. But the CD-ROM encyclopedia was certainly real and it played a featured role in this next Chronicles episode that originally aired in November 1985.

Small Step or Giant Leap?

This episode’s theme was “optical data storage.” Stewart Cheifet used a warehouse filled with boxes as the prop for his cold opening. He said it would take about 200 file boxes–or about 1,500 floppy disks–to match the storage capacity of 1 compact disc. In the studio, Cheifet had some more props, this time an assortment of optical storage devices that had come out during the past year, including a laser video-disc machine, a compact disc player, and a computer CD-ROM drive.

Cheifet asked Kildall if optical storage was just another “small step” forward in technology or was this a “giant leap” in technology. Kildall, admitting his biases in this area, noted that the industry had been working with magnetic storage since the 1940s. Optical storage could now get us a higher magnitude of information in the same amount of space. And if we could organize and index that large amount of information, then we could replace whole libraries–and maybe even the printed page someday.

Optical Discs Offered Higher Capacity But Still Faced Questions

Wendy Woods presented a brief report explaining the basics of optical storage technology. Narrating over B-roll, Woods said traditional magnetic storage could soon become a “fringe accessory,” as the vastly more powerful optical disc came close to mass production. Offering up to 1,000 times more storage than magnetic media in the same format, the read-only optical disc recorded information in small pits or “bubbles” burned in by a high-intensity laser. These encoded marks, much smaller than those on magnetic disks, were later read back by a low-energy laser beam.

Woods said the long-awaited “erasable” disc was actually a magneto-optical medium that used a laser to change the polarity of magnetized spots on the light-sensitive surface. Still in its infancy, the industry was dealing with several competing standards, from 120-millimeter read-only CD-ROMs to 130-millimeter five-and-a-quarter-inch writable discs.

Dr. Dave Davies, the general manager of 3M’s optical recording group, told Woods that CD-ROM was ideal for prerecorded databases where you would logically go in sequential fashion. But it was too slow for direct access of computer information, particularly software. 3M saw the need for a “rapid access” version where the disc would rotate at a constant angle or velocity and the optical head would zip back and forth reading the format information. The key was that read-once and erasable discs had to be physically interchangeable in the same drive.

Woods said the enormous capacity of CD-ROM–approximately 250 MB per side–had drawn increased attention from manufacturers at a time when computer sales were leveling off. Davies said the industry was in a slump because most computers were simply gathering dust due to the lack of enough easy, accessible software that made it worthwhile to use the machine. Optical storage provided an important part of the jigsaw puzzle in making computers useful to the average person.

As with the first personal computers, Woods noted, finding clever uses for the optical disc’s voracious storage was just a matter of time. But for a technology that showed such promise from the start, the future was even more remarkable. Davies said there was a very clear route for optical storage–to continue increasing the density of the disc to the point where the storage capacity started to approach that of the human brain itself.

A 20-Volume Encyclopedia Reduced to a Single Compact Disc

Tim Oren and Dr. Bob Kalthoff joined Cheifet and Kildall for the first round table discussion. Oren was one of Kildall’s employees, working as a user interface designed at Activenture. Kalthoff was the co-founder and CEO of Ohio-based Access Corporation.

Chiefet opened by asking Kildall what it was about optical storage that got him so fascinated. Kildall explained that about two years earlier, he was directing a product at Digital Research involving video discs. After the project was dropped, Kildall asked his board for permission to form a separate company to pursue optical publishing. He said his main motivator was figuring out what to do with all the information you could store on an optical disc. He said an encyclopedia was a logical prototype, so they decided to start there.

Cheifet turned to Kalthoff and asked if optical storage was something that would replace magnetic storage devices or instead work with them. Kalthoff said it was certainly “with”; he doubted that optical would ever replace magnetic storage. Cheifet asked why. Kalthoff said that we were at least five years away from the point where optical disc would even be possible for desktop computer applications. In the meantime, we’d likely see the availability of erasable optical-disc media that would be more effective in PCs.

Cheifet then asked Oren to demonstrate Activenture’s CD-ROM encyclopedia, known as the Grolier’s KnowledgeDisc. There was also a full set of the printed Grolier’s Academic Encyclopedia–all 20 volumes–as a dramatic prop. Cheifet said Kildall claimed all 20 of those volumes could be squeezed onto a single four-and-three-quarters-inch compact disc. Did he do it? Kildall said yes, although the CD-ROM version was text-only. He noted that the encyclopedia was actually stored in a ring about three-eighths of an inch thick on the disc, representing just 20 percent of its total storage capacity. And of the information stored, about half was the text of the encyclopedia and the other half was indexing information.

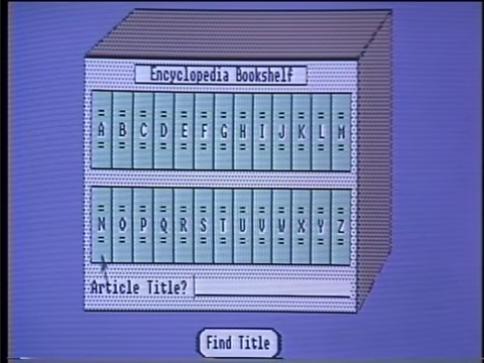

Cheifet asked Oren about the user interface design for the KnowledgeDisc. Specifically, how was using a mouse and a keyboard easier than just picking a book up off a shelf? Oren showed the main index for the KnowledgeDisc, which as he explained was arranged to look like books on a bookshelf (see below). The user could then just use the mouse to “point” to the volume they wanted to access.

As an example, Oren selected volume “A,” and clicked through a series of “finer and finer” index divisions to reach an article about the polar explorer Roald Amundsen.

Cheifet asked about the amount of storage involved with the KnowledgeDisc. Kildall said it was a 550 MB disc, which if printed out was enough to stretch 10 characters-per-inch from San Mateo to Denver.

Cheifet then asked about the search capabilities of the KnowledgeDisc. For example, how would he find information about “PBS” if there was no specific article with that title? Oren demonstrated the program’s word search function. A basic search for “PBS” found 33 occurrences in 16 articles. Kildall added you could also perform more complex boolean searches. For instance, Oren noted that some of the search results for “PBS” were for the chemical compound lead sulfide (PbS), so he redid the search excluding any results with the word “lead.”

Cheifet turned back to Kalthoff and asked how this technology was being used in industry. Kalthoff said the KnowledgeDisc was a “replicate” technology where each disc was stamped. His company dealt in write-once, read many times (WORM) discs, where a document was scanned and converted into a digital bitmap and fed into a 12-inch disc by a focused laser. The 12-inch discs had a capacity of 1 GB.

Berkeley Library Experimented with CD-ROM Databases

Wendy Woods returned with a remote segment from the University of California, Berkeley library, which used the InfoTrac CD-ROM database developed by Information Access Company (not to be confused with Dr. Kalthoff’s Access Corporation). Woods said anyone familiar with endless searching through periodical indexes could now appreciate the ease of searching on an IBM PC. Using InfoTrac, a video disc could contain the equivalent of a “good wall full of books.”

The system was part of an experiment conducted by the UC library to find the best optical storage reference bank. Bernie Hurley of the library said InfoTrac combined a very large and comprehensive database with the power of a microcomputer and allowed people to access information using non-traditional types of searching techniques. Woods said all the user had to do was type a search subject and all of the listings were there. You could even search for subtopics within a larger topic.

Woods noted that each of the InfoTrac video discs held 530,000 pages of from 1,000 magazines indexed since 1982. She added the system appeared to be user-friendly based on the logs kept by UC students. The system was not cheap, however. Woods said a four-terminal system with monthly video disc updates cost about $16,000 per year.

But as the price came down and the efficiency of the system increased, Woods said that optical storage was expected to become a lot more common in libraries. Hurley added that not only were more and more material now available in electronic form, some materials were only available that way. So reference rooms would have to evolve to handle not just traditional books, but materials in electronic form as well.

DEC Entered CD-ROM Market with Uni-File Standard

Stewart Cheifet presented the final remote segment, this one from the Information Industry Association’s 17th Annual Conference & Exhibition, held at the Shoreham Hotel in Washington, DC, from November 3 to 6, 1985. Cheifet said the compact disc (CD) was the “star of the show.”

Why? Because of how much information it could store–600 MB, or about 300,000 pages of work. With that kind of storage capacity, Cheifet added, applications were not hard to find at the show. There were CD-ROM encyclopedias, four years’ worth of newspapers on a single CD, and databases for prescription drugs and real estate listings.

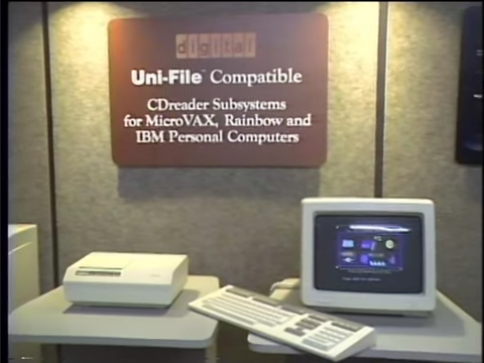

Cheifet said one of the newest players in the optical storage field was Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), which just came out with a CD-ROM drive for its MicroVax and Rainbow PC. The drive also worked with the IBM PC (see below). DEC offered a variety of scientific and technical databases, as well as customized applications such as a “Factory Information System,” which enabled a manufacturing company to put all of its maintenance manuals on a single CD. A maintenance supervisor could then consult the CD-ROM manual to retrieve repair instructions.

Ed Schmid, DEC’s optical storage marketing manager, told Cheifet the CD represented a “major discontinuity” in the cost of producing and distributing information. It was perhaps the biggest advance in distribution since the invention of movable type and the printing press.

But Cheifet noted the burgeoning CD-ROM business faced several problems. One was the issue of standards. DEC had proposed a format called Uni-File but there was still dissent within the industry over what standard would ultimately prevail. Another problem was the relatively slow access time of optical storage. Schmid said that wasn’t really a problem, however. The access time of a CD, depending on which manufacturer’s product you used, was about one second. That was admittedly slower than magnetic storage, where access time was often measured in milliseconds, but DEC said its user feedback suggested people were impressed with the information retrieval speed of CD-ROM.

The next question, Cheifet said, was when we would see the cost of CD-ROM come down to the point where it was affordable for the average user and not just business customers. He noted that Atari Corporation had promised a $700 CD-ROM drive would soon be available for its 520ST computer. Schmid was skeptical. He noted Atari CEO Jack Tramiel had announced a number of products in the past that never appeared or shipped. Based on DEC’s experience, Schmid said Atari would have a “tough time” producing a CD-ROM drive at its promised price point.

Regardless of price, Cheifet said the CD-ROM was still incredible. He noted that if you wanted to transmit all of the information from one CD online, you would have to transmit non-stop at 1200 baud for 46 days.

Was WORM Media the Future of Archival Storage?

Back in the studio, Fred Lloyd joined Cheifet, Kildall, and Bob Kalthoff. Lloyd was the head of software development for Information Storage Inc. (ISI), a Colorado-based company that produced optical drives. Cheifet opened by noting that Activenture’s KnowledgeDisc had no picture or graphics, just text. But there was a lot of room leftover on the disc. So he asked Kildall why graphics were not included. Kildall said adding images was the next logical step. Beyond that the goal would be to include some simple animations.

Cheifet asked Kildall to explain the difference between CD-ROM and WORM discs, the latter of which was produced at ISI. Kildall said he’d met Lloyd about a year earlier at COMDEX and he’d shown him a prototype for ISI’s WORM drive. A CD-ROM was like a book in that came pre-printed. But a WORM disc came blank and the user could write onto it once. ISI’s discs could store 100 MB per side.

Kildall asked Lloyd what the discs cost. Lloyd said they would sell for about $60 each. ISI’s media came enclosed in a tough plastic cartridge with a steel door (similar to a 3.5-inch floppy disk but larger). Kildall asked how people would use this type of drive. Lloyd said it could be used not only for backup but also online data–things that you used every day but did not change, such as documentation.

Kildall asked how a WORM drive would work with an IBM PC. Lloyd said the initial setup involved plugging in a card like you would any peripheral and running a simple installation program.

Cheifet noted that you could store about 1,600 files on a 100 MB WORM disc. How could you manage all that information? Lloyd said it was managed using ISI’s proprietary software, ISIDOS, which came with the drive. Lloyd then demonstrated ISIDOS, an add-on to PC-DOS, with the former helping the latter understand write-once media. Regarding Cheifet’s earlier point, while Lloyd’s sample WORM disc contained 1,600 files, the maximum capacity was up to 65,000 files. (Cheifet noted there was still 111 MB free on Lloyd’s demo disc.)

The demonstration itself was just the directory structure of ISIDOS. One thing Lloyd pointed out was that you could keep multiple versions of the same file archived on the disc, which was something you wouldn’t see on a magnetic drive. The revision system let the user see how their files changed on a daily basis. Kildall noted this made the WORM disc a perfect archival media.

Cheifet asked about the process of actually writing to the WORM disc. Lloyd said you could use standard DOS-style commands. And if you wrote a file with a previous version, the system would take note of that fact. Kildall said that short of scratching the disc surface, there was no way to get rid of a file once it was written. Lloyd said that was correct.

Cheifet asked Kalthoff about the application of WORM disc technology to industry and the workplace. Kalthoff said in his field they used this technology to implant 20,000 documents at 50,000-bytes (compressed from 4 million) onto a 12-inch, 1 GB disc. That information could then be transmitted to high-resolution terminals across an office. Kildall asked how the original information was stored. Was it microfiche? Kalthoff said yes, his company dealt primarily with engineering drawings, which originated as 35-millimeter film images.

Would Consumers Pay for CD-ROM?

In his closing commentary, George Morrow acknowledged the dazzling amount of storage space on a CD-ROM. But he noted bubble memory previously promised similar capacity and millions of dollars was spent on its potential–most of it in vain.

Any technology that had potential was going to be attractive, he said. But to really succeed it needed to fit into the environment it intended to serve. The read-only nature of CD-ROMs required specialized software and unique applications to make it fit within the normal operating system environment of a computer. Even worse, there would need to be different software for each operating system. And software was typically the most difficult and time-consuming part of any development project.

Morrow said another attribute that CD-ROM shared with bubble memory was the high cost. A CD-ROM player would cost at least $800 while their audio counterparts only ran about $200 to $300. The difference in price between the two would likely present a formidable barrier to home adoption.

Apple Promised Six New Computers By End of ‘86

The Internet Archive’s record of this episode is actually a rerun from May 1986, so that’s when this “Random Access” segment by Stewart Cheifet originally aired.

- Apple reported that for the first time, the Macintosh earned more money for the company than the Apple II. This was based on sales figures from the first quarter of 1986. Cheifet noted that Mac sales had boomed primarily due to desktop publishing.

- Apple also promised to release six new computers over the next 12 months. The first new product was expected to be the Apple IIx, a 16-bit computer that would be compatible with the IIe and IIc and possibly feature a detachable keyboard, built-in networking, a color graphics card, and four expansion slots.

- Zenith announced the first new CRT technology in several years. The new Zenith flat tension mask (FTM) promised to eliminate face-plate reflection.

- The Internal Revenue Service ruled tax software that provided “substantive tax instructions” would be considered a “tax return preparer” subject to potential legal liability and fines. Cheifet noted this ruling could put the tax software companies out of business.

- The Intel-NEC copyright lawsuit was headed to trial. The key issue was whether the microcode on a computer chip was “software” or “hardware.” Software can be copyrighted, Cheifet explained, while hardware could only be patented.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Zoomracks (Quick View Systems, $125), a database management program that displayed information as a series of cards. Schindler said the software “wasn’t perfect” but it was interesting and relatively cheap for a database program.

- California’s proposed computer privacy bill moved to the state Senate. In New York, that state’s legislature was considering a bill to criminalize “computer trespass.”

- The University of Maryland recently completed a study on the impact of personal computers on office work. Among other findings, managers moved from handwriting first drafts to typing them on computers, making less use of secretaries. Cheifet said other impacts included the move of financial analysis from mainframes to PCs and workers using copiers less as they could now use printers.

- A Virginia Tech researcher was trying to find one of the world’s earliest computers, the Harvard Mark III, which was reportedly dumped in a Maryland landfill in the late 1940s.

Robert J. Kalthoff, M.D. (1925-2002)

Dr. Robert Kalthoff was a psychiatrist by training. He earned his medical degree in 1948, and following six years of service in the U.S. Air Force completed his residency at hospitals in New York City and Cincinnati. He would eventually become a clinical professor at the University of Cincinnati.

In 1960, Kalthoff and a colleague, Dr. Paul Ornstein, started working on an automated document storage system for medical records. This led to the creation of Access Corporation in 1963. Two years later, Access released what a Cincinnati newspaper of the time described as a “non-electronic, electromechanical unit” that could search “an almost unlimited number of file cards in a matter of seconds.” Access initially leased its units for around $100 per month. The final product was not targeted specifically at the medical field–the first buyer was actually Xerox, which installed the unit in its Cincinnati branch office.

As best I can tell, Access Corporation remained a small, privately owned manufacturer of document management and imaging systems until its dissolution in November 1998. Kalthoff stepped aside as CEO in the late 1980s but remained chairman of the board. He passed away in August 2002 at his summer home in Michigan, according to the Cincinnati Enquirer.

KnowledgeSet’s Software Plans Hampered by Atari’s Failure to Deliver on Hardware

I briefly discussed Gary Kildall’s Activenture in a prior post featuring Tom Rolander, who was the company’s vice president of engineering. As Kildall mentioned in this episode, he spun Activenture out of an abandoned CD-ROM project at Digital Research.

Although the Grolier’s KnowledgeDisc was not released until a couple weeks after the episode first aired–sometime in early December 1985–the CD-ROM encyclopedia made its initial debut at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show back in June 1985. Activenture produced a demo of the program running on a CD-ROM attached to an Atari 520ST.

Now, you’ll recall Stewart Cheifet mentioned Atari’s plans to release a consumer CD-ROM for under $700, as well as DEC’s Ed Schmid suggesting this was yet another case of Jack Tramiel promising something he could not deliver. It turned out Schmid was right. The Atari CD-ROM drive never quite materialized. Nearly five years after that CES demo, Tom Byron wrote in STart Magazine that Atari was still insisting that their CD-ROM drive was just around the corner:

To what exactly the delays can be attributed are varied and complex to be sure, but one in particular stands out: a distinct lack of software.

“It’s basically a ‘chicken and egg’ situation,” Atari Corp. president Sam Tramiel told a room full of dealers and developers at last spring’s Comdex. “You can’t sell hardware that has no software, but on the other hand, who’s going to develop software for a product that doesn’t have a market yet?”

As far as I can tell, Atari never sold any CD-ROM drives to consumers. Scattered posts on Atari message boards suggest that there were as many as 1,000 “developer kits” that may have made their way into stores unofficially. But the promise of the 520ST as an entry-level optical storage machine was simply never fulfilled.

Indeed, as early as January 1986, Gary Kildall realized that Jack Tramiel had screwed him over on producing a CD-ROM drive. (Tramiel, perhaps heeding George Morrow’s warning, reportedly wanted to wait until CD-ROM players came down in price to match audio CD players.) Wendy Woods reported on The Source that Activenture had decided to produce its own sub-$1,000 hardware-software package that included a player, controller, and the Grolier’s KnowledgeDisc. I don’t know if Activenture ever produced such packages, but I did find a number of newspaper ads offering a free KnowledgeDisc with the purchase of certain optical storage drives.

Also in early 1986, Activenture also changed its name to KnowledgeSet after Activision–the video game publisher–complained. The name change was announced at a March 1986 conference hosted by Microsoft in Seattle to discuss CD-ROM technology. Kildall and Microsoft CEO Bill Gates were the featured speakers.

That conference produced yet another wrinkle in the battle over optical storage standards. Philips and Sony surprised everyone–including host Gates apparently–by announcing their new Compact Disc-Interactive (CD-i) standard, which promised the ability to combine audio, text, and graphics on the same media. But once again, promises did not immediately translate into reality, and it would be several years before CD-i made its way into any consumer products.

Meanwhile, the CD-ROM standard backed by a group of companies, including Microsoft and DEC, started to take off. Originally known as the “High Sierra” format, this morphed into the CD-ROM standard that became widely adopted for computers in the 1990s and early 2000s. DEC’s Uni-File was essentially a proprietary version of the original High Sierra standard. It never gained much adoption outside of DEC’s own products and was dropped by the early 1990s. DEC also quickly exited the software side of the CD-ROM business, discontinuing the database products mentioned by Cheifet in August 1986.

As I noted in my prior post, Gary Kildall didn’t stay in the CD-ROM market much longer either. He sold a majority interest in KnowledgeSet to the Wisconsin-based George Banta Co. Inc. in September 1987.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of November 19, 1985.

- Tim Oren joined Apple after leaving Activenture/KnowldegeSet. He went on to work for a number of different companies in the 1990s, including a two-year stint at CompuServe, where he led that company’s ill-fated efforts to transition from proprietary online services to the Internet. Oren would spend the 2000s working in venture capital before retiring in 2018.

- After leaving DEC, Ed Schmid started his own company, Simplify Development Corporation, in 1992. Later renamed eCopy, the New Hampshire-based company initially focused on creating software to convert paper documents into digital form. The firm later shifted into partnering with copier manufacturers, who offered eCopy’s technology as a scanner upgrade. Schmid spent 17 years as eCopy’s CEO before selling the company in 2009 to Nuance Communications for $54 million. Since 2010, he’s been a private investor.

- Fred Lloyd only had a brief stint at ISI. By 1988 he was a datacenter manager at Sun Microsystems, where he’d spend the next 19 years before retiring in 2006. Lloyd remained interested in optical storage technology, however, creating a database of Ham radio operators in 1992 called QRZ, which he produced until 2009. Lloyd also started a website for the project called QRZ.com that is still active today.

- The InfoTrac database was produced by Information Access Company (IAC), which was founded in 1977 and acquired by Ziff-Davis Publishing in 1980. InfoTrac continued as a CD-ROM database until the mid-1990s, when Ziff-Davis sold IAC to The Thomson Corporation. Thomson later merged IAC and InfoTrac into its Gale subsidiary. Gale, in turn, was sold to Cengage in 2007.

- Information Storage Inc. was acquired in 1989 by Literal Corp., a California-based joint venture co-owned by Eastman Kodak, C. Olivetti & C. SpA., and Kawasaki Steel Corporation.

- The Apple IIx would be released in September 1986 as the Apple IIgs. The final machine largely matched the specs described by Stuart Cheifet. Apple did not meet its six-machines-in-six-months promise, however, as the company did not release any further new computers until January 1987.

- The NEC-Intel lawsuit was about the microcode used in the Intel 8086/88 series of microprocessors. NEC filed a preemptive lawsuit asking a judge to decide if its own Intel-compatible microprocessors violated copyright law. In September 1986, U.S. District Judge William A. Ingram ruled that microcode was in fact “software” protected by copyright. Ingram later recused himself from the case after NEC discovered the judge belonged to an investment club that owned 60 shares of Intel. A different judge later held that NEC did not infringe any of Intel’s copyrights.

- Speaking of intellectual property lawsuits, the developer of Zoomracks sued Apple in 1989, alleging the latter’s HyperCard system infringed on a number of his patents. Apple settled the lawsuit by agreeing to pay the developer, Paul Heckel, a one-time licensing fee.

- The Information Industry Association merged with the Software Publishers Association in 1999 to form the Software & Information Industry Association, which still exists today.