Computer Chronicles Revisited 46 — KRON-TV, USA Today, KCBS Radio, and the Aurora/75 Graphics System

Few industries were transformed more by the rise in computer technology than the media. This next Computer Chronicles episode from October 1985 looked at the interaction of computers and the media, with a focus on practical applications in the television, radio, and newspaper industries. The final segment also returned to a favorite topic of the show, computer graphics, where the work of one of the guests would help lead to the creation of a whole new form of media–the computer-animated film.

Was “Electronic Delivery” the Future of Newspapers?

George Morrow was this episode’s co-host. Stewart Cheifet opened by demonstrating an online news service provided by Compuserve and running on a Macintosh. Cheifet said that in the past if you wanted this kind of information you would need to buy a newspaper or turn on the TV or radio. Now you could get the news whenever you wanted on the computer.

But Cheifet said that while there had been a lot of talk about the “electronic delivery” of the newspaper, not much had happened. Did Morrow think it would happen? Morrow said he didn’t think people would give up newspapers. And if you combined online news services with a laser printer, pretty soon you would end up with a high phone bill and a high paper bill. Cheifet added that the computer would also allow you to customize the news to your interests.

The First Computerized TV Newsroom

This episode was heavier on remote segments than in-studio round tables. Wendy Woods presented the first of the three remotes, this one from KRON-TV in San Francisco, the first television station in the United States to fully computerize its news operation. Woods said that computers had become an integral part of the newsroom. And faced with the daily task of sorting through mountains of information, the news department was a natural choice for computers.

Woods continued her narration over some B-roll of a KRON reporter–Rollin Post, who passed away in 2011–going about his day. The reporter could obtain his assignment, the stories being worked on that day, and messages from his computer. The computer system carried wire service bulletins throughout the day, which were signaled by beeps rather than the clicking noises of a traditional teletype.

The reporter’s job still required him to travel to locations, Woods said, to ask questions and take notes on a notepad. But with as many as 40 reporters in the field at one time and many fast-breaking stories arriving throughout the day, the computer streamlined the workflow.

KRON’s associate news director, Robert Hodierne, told Woods that in the three years since computers were introduced to the newsroom, people had forgotten what it was like to do their jobs without the machines. In fact, every once in awhile when there was a glitch, he said people would start to panic at the prospect of going back to using typewriters.

Overall, Hodierne said, computers sped things up immeasurably, often in subtle ways that were difficult to measure. For example, instead of having to get up from your desk and walk over to a clipboard to get wire service copy, you could get it right at your terminal. That might only save you 1 or 2 minutes but it added up over time. More importantly, the computer encouraged you to gain access to all of the information that was available to you.

Woods said that a reporter could use the computer to check the latest developments from the wire services while writing a story, list subtitles, and specify the pictures that should accompany the text. This information was then immediately accessible to the producers, editors, and artists who determined the final shape of the videotape package.

Another part of television that the computer had changed forever, Woods said, was the art department. Instead of slides and rough sketches, computer graphics now accompanied the text of a news story. Artwork and photos were combined to create a fast, flexible electronic library with a polished look.

But behind all of the computing power and convenience, Woods said, the sophistication of a network that links offices from San Francisco to Washington, DC, was one overriding concern. Hodierne noted that in the news business “speed” was very important. News operations scored their victories in minutes rather than days, and if you’re on-the-air three minutes before someone else with the big story, you won.

USA Today Used Computers, Satellites to Perfect National Distribution

Stewart Cheifet presented the next remote segment, this one focused on the national newspaper USA Today, published by Gannett. Ray Douglas, the systems director for the newspaper, told Cheifet that without computers, USA Today could not produce the kind of paper it did. Computers were used to collect news and information from various wire services, including the Associated Press, United Press International, and Gannett’s 85 local daily newspapers. The newsroom could also receive information from reporters in the field using portable computers.

All that information was then fed into one computer source, Douglas said, and once the pages for the newspaper were created and produced, the computer then took a facsimile image and converted it to a digital format, so that in roughly half-a-second it could be transmitted via the Westar 3 satellite to printing sites all across the country.

Cheifet said the USA Today computer system consisted of 12 DEC PDP-11/34 minicomputers running proprietary software. All 12 computers were networked and served only the editorial functions of the newspaper. Gannett had a separate mainframe that it used for corporate purposes, such as data processing and payroll.

While USA Today was probably the most computerized newspaper in the country, Cheifet said, it still did some basic things the old-fashioned way, such as page composition and layout. But Douglas said he hoped to enhance the computer system so it could take over those tasks as well. He said computerizing those functions would allow editors to make changes at a later deadline so that readers received a more up-to-date and precise product.

Douglas was also now experimenting with a computer system that let photographers in the field transmit color photographs back to the paper in the same way that reporters now sent text. He expected that in the short term it would be possible to transmit photos electronically and have them included in the next day’s newspaper.

To transmit the newspaper to its 30 printing sites around the country, Cheifet said USA Today used computer-controlled laser scanners with a resolution of 1,400 lines-per-inch. Computer-controlled “reconstructors” at each printing site then checked for errors, automatically requested the re-transmission of faulty scan lines, and produced a negative to make the final plates for printing the paper.

Back in the studio, Cheifet told Morrow that USA Today was perhaps best known for color graphics such as its weather chart, which ironically were still made by artists sitting at a desk. Morrow said that probably had to do with reliability. Microprocessors had been around since the mid-1970s but it was only now that industry felt comfortable enough with the technology to rely on it. After all, you didn’t want your television program going haywire in the middle of a segment–or miss your newspaper deadline either, Cheifet quipped.

Working in Radio Now Required Computer Training

Wendy Woods returned for our third remote segment, which profiled KCBS news radio in San Francisco. Woods said that everything the KCBS listener heard was compiled and written on a computer. Even the anchors read copy that was either printed out or displayed on their terminals.

KCBS was the first broadcast station to computerize, Woods said, creating a virtually paperless newsroom and a model for other broadcasters. The KCBS operation relied on 12 terminals hooked up to a minicomputer. The system had 140 MB of total storage–enough for 2 years worth of stories.

This system had been virtually bug-free since it first came into operation in 1979. Ed Cavagnaro of KCBS said that reliability was very important, and now more and more television and radio stations were using similar systems. Overall, he thought everyone was pleased with the computerized newsroom.

Valerie Coleman, a KCBS anchor, told Woods that she loved the computer system, noting it was clean, quiet, and efficient. The only problem she’d experienced was eye strain.

Woods said another issue with the computerized newsroom was the need for training. A reporter could not just walk in to KCBS off the street without computer experience. Still, the computer had produced an accurate, efficient, and timely news operation. Indeed, the CBS network now had a similar system, only bigger.

Computer Graphics Revolutionized Television–But What About the Movies?

The only round table for this episode delved into the use of computer graphics and visual effects in the media. Dave Patton and Rodney Stock joined Cheifet and Morrow in the studio. There was also an Aurora/75 graphics system. Morrow asked Stock, the founder and president of the Computer Arts Institute, to explain the mix of hardware and software in the system. Stock said the hardware included a unique form of high-bandwidth memory that could store an entire image in one place. He said the software was also fairly sophisticated as it needed to handle a single image with a minimum of around 250,000 pixels, each assigned a specific color.

Morrow asked if the Aurora system would plug-in to something he could buy at his local computer store. Stock said the Aurora plugged into an IBM PC-AT and there were other graphics systems that could work with something smaller like an IBM PC/XT. Morrow asked if you needed a hard disk drive with this type of system. Stock said you typically would.

Cheifet then turned to Dave Patton, a vice president and co-founder with Prism Arts Group, for a demonstration of the Aurora, which was hooked up to an PC-AT, a graphics tablet, and two RGB monitors. Cheifet asked how much the system cost. Patton said the base price was about $32,500.

Patton showed the Aurora generating a simple-cycle animation of a rotating galaxy. Morrow interjected with a follow-up question regarding price–was that $32,500 for the complete package or just the software? Patton said it included the hardware, although Stock clarified that CPU and the RGB monitors were not standard. Stock said that good RGB monitors would cost an additional $2,300 to $5,600 apiece.

Patton continued his demonstration, this time showing the image of a computer-generated cigarette with a simple animation cycle for smoke coming off the end. Morrow asked if it was possible to do cycle animation of the ash moving back to make it appear as if the cigarette was burning. Patton said that was possible and the tools were available to make that happen fairly easily. Stock added there was a more expensive Aurora system that could do those kinds of animations even more readily.

Morrow asked Stock if they taught these animation techniques at the Computer Arts Institute. Stock said they did.

Patton showed one final demo, this time of a title screen with snowflakes coming down around the text. This was actually done by painting striped rows of snowflakes down the screen but alternating the individual snowflakes between the background color (blue) and the snowflake color (white) to make it appear as if the snow was falling in a random pattern.

The round table then shifted to some discussion over B-roll of various computer graphics projects created by Pacific Data Images (PDI). (Some of the footage used here was previously seen in a June 1985 Chronicles episode where Wendy Woods profiled PDI and interviewed its founder, Carl Rosendahl.) Stock explained that PDI was a production house for computer graphics. They didn’t buy or sell computers. Rather, PDI assembled its own hardware and proprietary software to generate computer graphics. Most of PDI’s work was done for national accounts, such as NBC.

The B-roll started with various animated introductions produced by PDI for NBC and other television networks and stations. Cheifet asked about the cost of producing such intros and logos. Stock said specialty houses like PDI typically charged between $2,000 and $5,000 per second for 3D animation. Morrow expressed surprise at that figure, but Stock pointed out that these animations were used over and over again by national networks so they needed to look good.

Cheifet asked if there were any actual “cameras” involved in the animation process. Stock said no, everything was created digitally inside the computer and went through a frame buffer directly onto videotape. In response to a follow-up question from Morrow, Stock elaborated that the 3D images could be moved and viewed from any angle. He also noted the “soft edges” on the images. There was also no flickering–what was called aliasing–in the image field.

Stock then walked though how PDI used a combination of computer graphics and live-action models to create an animated introduction for a Brazilian television show.

The final sample piece shown was Chromosaurus, a PDI short featuring chrome dinosaurs running around an open landscape. Stock said this was a demonstration of where 3D graphics wanted to go. You used reality as a metric to establish your ability as an artist before going to surrealism. That is to say, once you could model dinosaurs and chrome, you could then have “chromosaurs.”

Cheifet concluded by asking Stock–who previously worked on computer graphics for Lucasfilm–whether movies or television were the primary driver of this technology. Stock said it was primarily television. There were some uses of computer graphics in movies, such as a brief sequence done for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan by Lucasfilm, but it was such a specialized effect that there weren’t that many movies using them.

Apple Cut Prices, ETAK Offered First In-Car Navigation System

Stewart Cheifet presented this episode’s “Random Access,” which was recorded on or about October 5, 1985:

- Cheifet said computer makers were starting early with their holiday price cuts. Apple announced the price of an Apple IIc with a black-and-white display would now be $995, down from $1,295; and the Apple IIe with 128 KB was now down to $945 from $1,145. Apple also announced price cuts for the Macintosh and the color version of the IIc.

- IBM released a new version of the PC-AT with a 30 MB hard disk drive. It would sell for $200 more than the current version of the AT with a 20 MB hard disk.

- Apple and Digital Research settled a lawsuit over allegations that GEM violated the copyrights on the “look and feel” of the Macintosh operating system. Digital Research agreed to modify its software. (I covered this settlement in a previous blog post.)

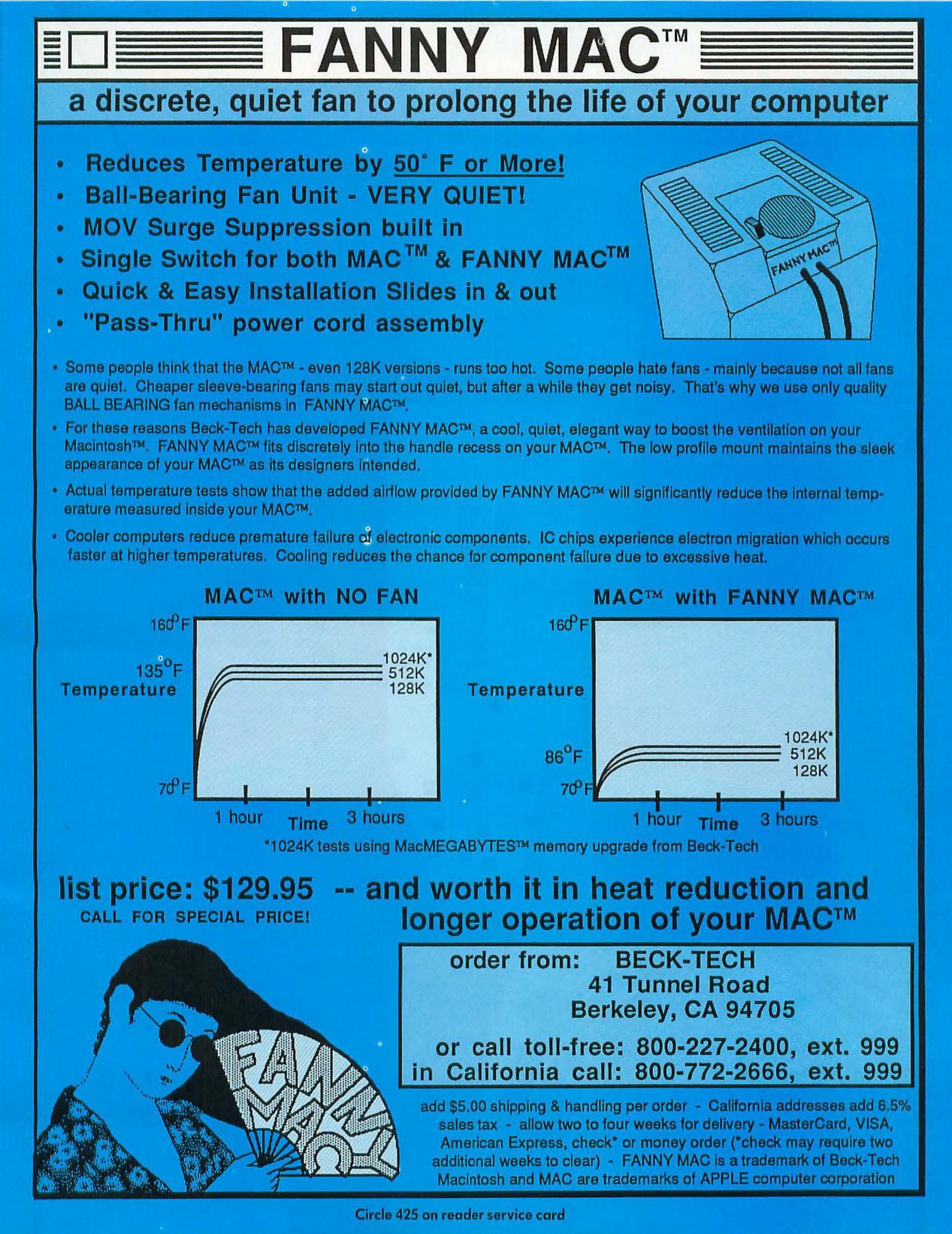

- Just weeks after Steve Jobs left Apple, Cheifet quipped, there was already a cooling fan now available for the Macintosh. (Jobs detested fans and refused to put one in the Mac.) Beck-Tech now offered a fan that promised to reduce the inside temperature of the Mac from 135 degrees (Fahrenheit) to 86 degrees.

- Sen. Paul Trible of Virginia agreed to amend his proposed bulletin-board pornography bill to meet the objections of the ACLU and several BBS operators. Cheifet said witnesses told a Senate subcommittee that there were hundreds of boards around the country that were dealing with child pornography. (The bill never actually made it out of the Senate.)

- The Soviet Union decided to buy MSX computers from Japan, ordering over $1 million in machines for use in schools.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Bakup (InfoTools, $150), a hard-disk backup program. Schindler said “no matter how hard I try,” he couldn’t make any mistakes while using the program.

- ETAK was now selling a $1,500 product for cars called Navigator. The device displayed a map of the driver’s location and destination on a CRT screen. Cheifet noted the Etak did not rely on radio signals. Rather, it used an electronic compass, motion sensors, and a computerized map database. Etak claimed its Navigator was accurate to within 50 feet.

- The nation’s biggest piano-roll maker said it was converting 10,000 of its piano rolls into floppy disks that can be played back through a Commodore 64 or Apple IIc.

- A computer scientist used a $10 million Cray X-MP supercomputer to discover what was (so far) the world’s largest prime number–2 to the 16,091st power minus 1. This number had over 65,00 digits, Cheifet said, and replaced the prior largest prime number discovered just two years earlier.

Aurora Was Yet Another Orphaned Xerox PARC Project

In his closing commentary, Paul Schindler predictably lamented the growing encroachment of computers upon the traditional newsroom. He said that while the “news was fresher” thanks to computers, the final product didn’t “flow as well as it used to.” And while news copy was now written faster, that didn’t mean it was necessarily better. One can only imagine what Schindler–long retired from the industry–thinks about the central role that Twitter and social media now plays in journalism. (Paul does have a blog but I’ve never seen him on Twitter.)

Of course, this Chronicles episode aired more than a decade before the Internet started to seriously disrupt the traditional model of journalism. And as George Morrow observed, there was no immediate threat to print newspapers in 1985 given the cost of accessing information through a service like Compuserve, which still charged for access by the hour. Indeed, even today when many news sources are wholly online there are still newspapers that publish print editions, including the venerable USA Today.

But this episode was definitely focused on how computers were used by the media industry itself rather than consumers–who after all were still buying newspapers and listening to the radio. The Aurora/75 was a good example of how the market for 3D computer graphics was definitely not ready for the average PC desktop. According to a June 1984 article by Dick Phillips for the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, a full-blown Aurora system cost about $130,000. The first such system was actually sold to KRON-TV in San Francisco, and by mid-1984, Aurora Systems said it had sold a total of 25 units.

If you’re playing the Computer Chronicles Revisited drinking game, you can take a shot now, as Aurora Systems itself was started by–wait for it–a former Xerox PARC employee, in this case Richard Shoup. Shoup, who died in 2015, developed his first prototype for a computer paint system, known as Superpaint, while still at PARC, but he told Philips that “Xerox wasn’t paying much attention to it,” as management didn’t see the system as a practical means of producing business graphics.

In 1977, Shoup offered his Superpaint system to Damon Rarey, the graphics director for a daily magazine program produced at KQED-TV in San Francisco, for free if he could “find a use for the system on the show.” Shoup and Rarey ended up becoming partners and co-founding Aurora Systems in 1980. Rarey also started Prism Arts Group as an illustration and animation company to service corporate clients.

Aurora Systems was acquired by New York-based Chyron Corporation in June 1994. As I explained in a prior post, Chyron itself merged with Sweden-based Hego AB in 2013. As for Prism, it dissolved shortly after Rarey’s death in 2002.

Stock Co-Founded Pixar

Although the final segment of this episode focused on the work of Pacific Data Images–the company that would go on to become the feature film studio DreamWorks Animation–Rodney Stock was actually a co-founder of what became PDI’s main “rival” in the computer graphics space, Pixar.

Stock got his start engineering flight simulators for Evans and Sutherland, an early computer graphics firm, in the 1970s. He then worked at Ampex where he worked on a digital paint system (not the Aurora). By the early 1980s, Stock was the graphics engineering manager at Lucasfilm, where he led the team that developed what became known as the Pixar graphics computer. As Stock noted on Chronicles, one of the first finished animation pieces produced by his division was a one-minute sequence seen in Star Trek II, where Dr. Carol Marcus made her crowdfunding pitch for the Genesis project.

George Lucas’ divorce prompted him to sell off the computer graphics arm of Lucasfilm to Steve Jobs in February 1986, about four months after this episode aired. Jobs took a majority interest in the company with Pixar’s 43 employees, including Stock, receiving the remaining shares. At the time, there was no talk of Pixar getting into the feature film business. To the contrary, Jobs saw Pixar as a hardware company and initially planned to sell the Pixar computer itself at $125,000 a pop.

As for Rodney Stock, I could not find any definitive information on his activities since the mid-1980s. As Cheifet mentioned, Stock did serve as founder and president of the Computer Arts Institute, a private school that provided specialized courses in computer graphics. As best I can tell, the Institute fizzled out sometime in the late 1990s.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of October 10, 1985.

- There were two episodes broadcast in between this one and the last one that I covered. Unfortunately, they are among the episodes still missing from the Internet Archive.

- Robert Hodierne had a long career in journalism starting with his work as a photographer covering the Vietnam War. He joined KRON-TV as its associate news director in 1983 and remained there until 1986. In 1987, he took a sabbatical from journalism and spent the next three years sailing around the Pacific Ocean before settling in Japan. He returned to journalism in 1993. In 2008, he joined the University of Richmond in Virginia as an associate professor of journalism and taught there until his retirement in 2021.

- Ray Douglas (1949-2007) left USA Today in 1990 to join the New York Times, where he ultimately became chief information officer for the newspaper’s parent company. Douglas retired in 2001 and passed away in 2007.

- Ed Cavagnaro joined KCBS Radio in 1977 as a promotion assistant. He moved to the newsroom a few months later and remained there until 2015, when he retired after serving as news and programming director since 1988.

- Valerie Coleman–now Valerie Coleman Morris–worked at KCBS on both the radio and television sides in the 1980s. In 1994, she joined CNN as a business anchor and remained with the network for 12 years. Since 2007, she’s been an author and speaker promoting financial literacy to women and people of color.

- Dave Patton joined the advertising agency Pittard Sullivan in 1991 and remained there for a decade, primarily working out of its Munich, Germany, office. After a four-year stint at Starz Entertainment in the early 2000s, Patton is now retired and living in Nevada where he runs his own fine art photography studio.

- Star Seimitsu was the Japanese company that sold those MSX computers to the Soviet Union. According to contemporary reports, the USSR purchased 4,000 8-bit computers at a total cost of $1.2 million.

- Anti-BBS porn crusader Paul Trible only had a brief career in the U.S. Senate, serving a single term representing Virginia. But he recently announced his retirement after more than 25 years as president of Christopher Newport University.

- ETAK was started in 1983 by a group of six former employees from SRI International. Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell provided the initial funding. The digital road map database component of the Navigator later attracted Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, which acquired ETAK in 1989. But as ETAK co-founder Stan Honey noted in a history of the company, things came “full circle” as ETAK’s assets were ultimately merged into TomTom N.V., the Dutch company that produces modern-day satellite navigation devices for cars.

- David Slowinski was the computer scientist who discovered what was then the largest-known prime number. The record only stood for about four years. In 1989, a group known as the Amdahl 6 discovered a prime number that was 37 digits longer than the one found by Slowinski. The Amdahl 6 record has since been broken many more times. As of March 2022, the largest known prime number has over 24.8 million digits.