Computer Chronicles Revisited 39 — MSX and COMDEX in Japan '85

As we round the home stretch for the second season of Computer Chronicles, the show makes its first extended foray abroad. The next two episodes focus on Japan. This first episode from May 1985 examines the state of the Japanese personal computer market, while the second looks mostly at the country’s robotics industry.

Had Japan’s Window of Opportunity Closed?

Stewart Cheifet presented his cold open from Japantown in San Francisco. He said that while many Japanese products had become popular in the United States, one export that had not been very successful was the Japanese computer. This episode would explore why that was the case.

In the studio, Cheifet asked Gary Kildall if the window of opportunity for Japanese computer manufacturers to “invade” the U.S. market had closed or was it still possible they could move in. Kildall noted they were talking about packaged personal computers, as opposed to other areas related to computing where the Japanese were successful. That said, the Japanese manufacturers tended to focus on their home market first. They didn’t have the distribution, marketing, and support channels in the United States to sell personal computers. The potential was there, Kildall said, but American manufacturers were hoping to keep the Japanese offshore through their own ingenuity.

Japanese Computer Manufacturers Were “Waiting and Watching”

Robin Garthwait narrated some lovely B-roll footage on Japan’s history in the personal electronics market. She said that when the first Japanese transistor radio appeared on the market in 1955, few people at the time realized it was the start of the “Japanese economic miracle.” From radios to stereos, from cars to cameras, the Japanese had marked success in one market after another around the world.

Garthwait said Japanese technical proficiency was renowned and the country’s professional base seemed geared towards high tech. On a per capita basis, Japan had four times as many engineers as the United States. But in spite of the country’s dominant position in consumer electronics, the Japanese had not done so well with computers–at least those manufactured for export. Japanese computer companies owned about 10 percent of the world market, while the United States had 80 percent. And within the United States, which accounted for over half of the global computer market, Japan held only a 2 percent market share.

But, Garthwait pointed out, the Japanese had excelled in producing components, hardware, and peripherals, which didn’t require software development or extensive customer support. With some exceptions, Japanese manufacturers were content to leave systems integration and service to domestic affiliates. Like the early years of Toyotas and Datsuns, however, the Japanese had learned since their first attempts and their more recent approach to home computer exports seemed to be one of “waiting and watching.”

Could MSX Be the Answer?

Rather than go into the usual studio round table, the next segment featured Stewart Cheifet on location in Japan, where he interviewed a number of people associated with the Japanese computer industry. Standing in front of a Japanese computer store, Cheifet noted that Japan was the world’s second-largest computer market. More than $24 billion worth of computers had been sold in the country. But the world’s largest market was the United States–more than four times the size of the Japanese market. So no matter how successful a Japanese computer manufacturer was in the domestic market, Cheifet said the temptation was irresistible to want to sell Japanese computers in the United States.

Katsuro Miyakoda, an editor with the Japanese computer magazine I/O, told Cheifet through a translator that most Japanese computers were not based on the IBM PC, which was the de facto standard in the United States. Instead, Japanese computer manufacturers were struggling to make special machines for export to the United States, which were different than the computers they sold in Japan. He said there were two major problems Japanese companies needed to resolve in developing machines for export: poor documentation and a weak user interface.

Cheifet said the distinct difference between Japanese and American computer users had not been overlooked by the Japanese makers and could be seen in any Japanese computer store. The Japanese retailers had seen a profusion of low-cost machines attracting young customers, and the “accent” was definitely on entertainment software. Yukio Mizuno, a senior managing director with electronics manufacturer NEC Corporation, told Cheifet that the Japanese computer industry was in the process of transitioning from the hobbyist market to the business-oriented market. The personal computer market in the United States had already made this transition.

Cheifet noted that NEC was the “IBM of Japan,” with a 58 percent share of the domestic market. But like most Japanese manufacturers, NEC had seen disappointing sales in the United States. NEC seemed to be waiting for improvements, particularly in the home computer market. Mizuno said that NEC had tried selling personal computers to the home market in Japan. However, the current software and processors were not sufficient for home use. But the home market would gradually increase over the next 5 to 10 years.

Katsuro Miyakoda added that for Japanese computers to sell in the United States, they needed some unique new software. That meant finding good third-party developers. Japanese makers also needed to find retailers to sell their own software. He suggested the reason NEC and other Japanese companies were not pushing harder in the United States was that they were not ready yet. They were saving their strength for the future.

Cheifet said that Japanese industry had a firm tradition of introducing new products in the domestic market first. Only after Japanese consumers responded favorably would the product then go overseas. But the computer was a special case. Kazuhiko Nishi, the co-founder of Tokyo-based ASCII Corporation, told Cheifet that transplanting Japanese-built software to the American market–especially applications–was very hard. There was also no established technology for writing operating systems or communications software not in Japanese. Nishi said the core problem was that it was “impossible” to ask Japanese engineers to speak English–and the computer was invented in the United States.

Cheifet said that of all the new Japanese computer products, the most closely watched was MSX, which ASCII Corporation co-developed with Microsoft Corporation in the United States. (Nishi previously worked at Microsoft.) MSX was an 8-bit operating system aimed at the home market and designed to solve the problem of incompatible machines. So no matter who manufactured the computer, if it ran on MSX, it would run any software written for MSX–an admirable concept, Cheifet observed, with its share of problems.

I/O magazine’s Miyakoda noted that in Tokyo, MSX machines were sold at discount prices. This wasn’t because the product was popular, but rather because MSX was not that successful. Like inexpensive computers in the United States, it was a “loser’s game.” The MSX machines had weak business capabilities, Miyakoda said, as they lacked disk drives and had limited memory storage and poor screen resolution–all of which were below U.S. personal computer standards. Conversely, Nishi said MSX would be important for the Japanese computer industry because it provided for a “very clear separation” between software and hardware.

Cheifet explained that MSX was a “hybrid” of eastern and western technology. Although made in Japan, it was designed in the United States. And while MSX remained an unknown, it represented Japan’s unconventional approach to a routine obstacle in the computer industry–compatibility. Miaykoda said that if the Japanese manufacturers made machines to the IBM standard, it would just lead to a price war. It would not improve anything. Instead, the Japanese companies were trying to produce machines with higher standards and a higher level of functionality. The bigger the gap between Japanese and American computers, he said, the better the opportunities for new Japanese-made machines.

NEC’s Mizuno added that the compatibility problem worked both ways–it was equally difficult for IBM-based machines to gain a foothold in Japan due to the differences in the Japanese and English alphabets. Cheifet said that faced with this language obstacle, an uncertain market, and cutthroat competition, the Japanese companies were striking out in all directions to get a jump on new computer technology.

First Japan COMDEX Features Early Clamshell Laptop and Smart Watch

Cheifet transitioned his narration to B-roll footage of the first COMDEX in Japan show, which took place in late March 1985. He said the products displayed ranged from the very clever (small robots) to the very advanced (CD-ROM), with an emphasis on Asian applications. Fujitsu displayed their new Japanese- and Thai-language word processors. Cheifet noted that before computers, there was no practical way to type the thousands of characters called kanji in the Japanese language. To deal with the complexity, different systems had been adopted. For example, one program recognized the corners of the character, which was chosen by the user on a keyboard. Another company, CICS, had done away with the keyboard completely, with a “hand writer” that treated kanji as graphics. The user entered the characters on a digitizing pad, which the software then interpreted using a software dictionary.

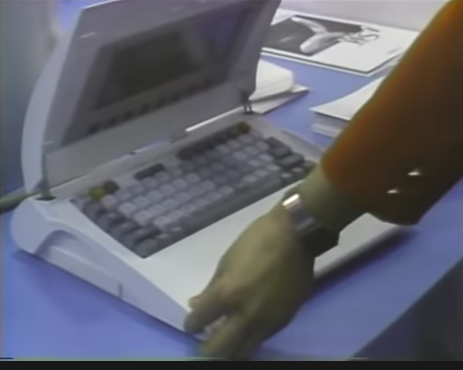

Fujitsu also showed off a new portable 16-bit computer with an 80-by-25 display. The machine came standard with 128 KB of memory–expandable to 448 KB–and up to 512 KB of ROM. Cheifet said the Fujitsu machines would be priced starting around $1,300. Another “unusual” portable on display was the Ampere WS 1, which featured a “bizarre clamshell case” hiding a full-sized screen and a Motorola 68000 chip. The operating system was based on APL, a programming language developed in the early 1960s for scientific applications.

But Cheifet said the “most compact machine” at the show was the Epson RC-20 Wrist Computer, a watch-sized computer-on-a-chip with a communications port, 2 KB of RAM, and four built-in programs. COMDEX also featured a number of advanced computer peripherals, notably the 540 MB CD-ROM discs displayed by Denon and Sony. Sony also displayed a larger-sized laserdisc with a capacity of 3.28 GB–or about 30,000 pages of text.

Foreign language instruction applications were also a big item at COMDEX, Cheifet said, including a “computerized mystery story” published by the Limelight Company. The program used an audio cassette synchronized with the screen’s graphics, providing a “complete audiovisual language lesson.”

Hitachi Aimed to Be World’s Top Computer Company by 2000

The final segment returned to the California studio for a round table. Gary Kildall opened by noting there were a lot of foreign manufacturers that would like to bring computers to the United States, but it was really the Japanese challenge that domestic manufacturers were concerned about. To discuss this “challenge,” Michael Miller and Christopher Mead joined Kildall and Cheifet.

Kildall asked Mead, publisher of the Phoenix-based Japan High Tech Review, why Japanese computers like the Sharp X1 or MSX had yet to be introduced in the United States. Mead said the basic reason was language. Japanese kanji needed to be represented graphically and thus required more computing power than the western alphabet. Until about a year ago, Mead said it was effectively impossible to represent the Japanese alphabet on personal computers. This kept Japanese companies far behind the American industry.

Kildall followed up by asking about Japan’s domestic market. Were Japanese computer makers simply looking to establish their success at home before coming to the United States? Mead said that had been true with many Japanese companies. Their attitude was you didn’t want to embarrass yourself outside before you fist perfected your product at home. Mead added there was also a language problem on the English side, as when it came to software it was important to speak the same language as your customers. Kildall pointed out this problem also extended to translating manuals and documentation.

Kildall then turned to Miller, the west coast editor for Popular Computing–the presenting sponsor of Chronicles this season–and asked about MSX. Kildall said that was a standard that could compete with a machine like the Commodore 64 or the Atari 8-bit machines. Were those two American companies keeping MSX out of the American market? Miller explained that MSX was a standard that would in theory be adhered to by a number of Japanese companies. Many of these machines were shown at the 1985 Winter Consumer Electronics Show and already on sale in Japan. But as of yet, Mead said nobody had successfully brought an MSX machine to market in the United States. It seemed to Miller that the MSX computers were not as up-to-date when compared to the newer Commodore and Atari machines.

Kildall asked if the Japanese had any potential advantage in terms of manufacturing, especially given that many computer parts were already produced in Asian countries. Miller concurred that most American manufacturers, including Commodore and Atari, relied on components built in either Japan or South Korea.

Cheifet asked Mead if the Japanese had actually solved the language problem and would now pose a greater challenge to American computer manufacturers in the future. Mead said it depended on what you meant by “the future.” He didn’t see any immediate changes in the U.S. market over the next six months. It was more of a long-term problem. For example, Hitachi had an internal goal of becoming the world’s number-one computer company. The first step towards that was becoming the world’s number-one semiconductor manufacturer. Mead said Hitachi hoped to reach this first goal by 1990. Then Hitachi hoped to pass IBM to become number one in computers by 2000.

Cheifet closed by asking about computer peripherals, a market where Japanese companies had been very successful in the American market. Why was that? Mead replied the language barrier was less of an issue there. And many American designers were deciding that since the products would eventually be produced in Japan anyway, they might as well go directly to the source when creating new products.

America’s “Secret Weapon” in the Computer Wars

Paul Schindler’s closing commentary argued that Silicon Valley was unlikely to go the way of Detroit or Pittsburgh when it came to dealing with a potential Japanese “invasion” in the computer market. While the Japanese knew how to both “innovate” and “imitate,” Schindler said American industry had its own “secret weapon” that may never be overcome–the United States was a keyboard society. Japan was not. In other words, the previously discussed language barrier would prove too much for Japanese manufacturers to overcome.

Attack of the AT Clones

Stewart Cheifet presented “Random Access,” which dates the episode in early May 1985.

- There were a new round of IBM PC/AT clones heading to the market. Compaq announced both a desktop and a portable that were AT-compatible. Compaq said its desktop model was 30 percent faster than the IBM. NCR also announced the PC8, an AT clone that could serve up to 16 users. The Compaq and NCR clones both relied on the Intel 80286 microprocessor, the same used in the IBM PC/AT.

- There were also rumors that Tandy and Hewlett-Packard were preparing their own AT clones. The Tandy machine would possibly be shown at the forthcoming Atlanta COMDEX show.

- AT&T said it would begin selling its own 32-bit UNIX-based microprocessor as part of its efforts to expand the use of its UNIX operating system. Meanwhile, Xerox said its new computers would be AT&T-compatible, meaning Ethernet and AT&T’s StarLAN networking standards would work interchangeably.

- Apple formally announced the end of the Lisa, which had been re-branded as the Macintosh XL. Cheifet noted the Lisa had never been successful, and Apple had cut the price from its original $10,000 to under $4,000. Apple said it would focus on making more “Big Macs” in the future.

- For all the talk in this episode about the future of Japanese computer exports, Cheifet said Japanese companies were actually investing heavily in Silicon Valley itself. For example, Fujitsu was now a major investor in mainframe manufacturer Amdahl Corporation. Overall, Japanese corporations now owned or controlled about 140 industrial plants in California.

- Paul Schindler presented his weekly software review, this time for Copy II PC (Central Point Software, $50), a utility that allows users to make backup copies of otherwise copy-protected software to a hard disk drive. Schindler said he used the program to copy dBase III to his hard drive. And while he acknowledged people could use Copy II PC illegally, the same was true of a butter knife. That didn’t mean we should ban butter knives, Schindler said.

- Cheifet said there was a growing trend of “mini” versions of best-selling business programs. For example, MicroPro planned to release a mini WordStar that would sell for half the price of the full version.

- Computers in schools were booming. The number of computers in schools increased by 75 percent in 1984, Cheifet said. Nearly 300,000 computers were purchased by schools that year. More than 85 percent of public schools reported using computers, with the average school having eight machines.

- People Express Airlines had a new computerized reservation system that allowed customers to purchase tickets using a touch-tone telephone.

- IBM released the first “talking, blinking” ad in print. Big Blue took out an ad in a recent issue of the French magazine Le Point that featured an embedded microprocessor, battery, and speaker, that caused the Charlie Chaplin-themed ad to light up and play Christmas music when the page was turned. Cheifet said IBM paid $2 per issue for the computerized ad. The magazine sold 300,000 copies of the issue on its first day.

What Was MSX?

The MSX standard had been mentioned in a number of previous Chronicles episodes before one of its developers, Kazuhiko “Kay” Nishi, appeared on-camera in this program. So what exactly was MSX? And why have you probably never seen an actual MSX machine?

Basically, MSX was a computer architecture based on the Zilog Z80 microprocessor. The Z80 was hardly new or innovative technology even in 1985. Z80-based machines had been on the market since the late 1970s, and in fact were commonly used in microcomputers running Gary Kildall’s CP/M operating system, such as the Osborne I and KayPro II. At the lower end, the Z80 powered the original Radio Shack TRS-80.

As the MSX Resource Center explains, the MSX standard was an attempt to create “a hybrid of a videogame console and a generic CP/M-80 machine.” There’s some debate over the origin of the name “MSX.” One theory is that it stood for “Microsoft Extended BASIC,” which was the software designed by Microsoft to use with the standard. Nishi himself would claim in the 1990s it stood for “Matsushita Sony X-machine.” with the “X” representing whatever company happened to make a particular computer based on the standard.

While MSX machines did enjoy success in much of the world, they never gained a foothold in the United States. Indeed, the MSX Resource Center said the only machines that made it to the American market were “an early SpectraVideo model and the Yamaha CX-5M, which while essentially an MSX, was marketed as a musical instrument rather than a home computer.”

Nishi Clashed with Gates Over Giant Brontosaurus

Kay Nishi himself had a background in publishing. He co-founded ASCII Corporation in 1977, which published a magazine called ASCII. Nishi would then strike a licensing deal with Bill Gates to sell Microsoft BASIC in Japan in 1978. Eventually, Nishi became Microsoft’s vice president of sales in Asia. This relationship led to the development of MSX.

But that relationship later soured. According to a May 1993 Wired profile of Nishi written by Bob Johstone, even as Microsoft sales in Japan soared, “Gates became increasingly impatient with Nishi’s unorthodox approach to business.” The Microsoft CEO was particularly irked when Nishi decided to promote MSX with a $1 million publicity stunt “involving a life-size model of a brontosaurus.” By 1986, the Microsoft-ASCII partnership was dissolved.

Despite this blow, Nishi took ASCII public three years later, in 1989. Nishi also went on a buying spree. Johnstone noted that ASCII corporation entered a “slew of new businesses” during this time, buying everything from a movie distributor to a travel agency and a helicopter rental company. By 1992, however, ASCII Corporation had accumulated $320 million in debts and its stock price was down to just $5 per share (after reaching a high of $175). In 1993, a consortium of Japanese banks bailed out ASCII Corporation.

ASCII Corporation would continue to operate under a number of different owners until April 2008, when the original publishing business was absorbed into another publisher called MediaWorks. The new company, ASCII Media Works, continues today as a subsidiary of Kadokawa Group Holdings, Inc.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of May 21, 1985.

- NEC’s Yukio Mizuno passed away in 2003 at the age of 73. According to the IPSJ Computer Museum, Mizuno was NEC’s top personal computer executive and helped to create the 16-bit PC-9801, which was popular in Japan’s business market.

- Michael Miller has had a long career in computer journalism. He left Popular Computing not long after his Chronicles appearance to join InfoWorld, where he served as executive editor and editor-in-chief. He moved to PC Magazine in 1991, where he served as editor-in-chief for 14 years. In 1997, he also became editorial director for the magazine’s parent company, Ziff Davis. After a brief stint as Ziff Davis’ Chief Content Officer, Miller joined the Ziff brothers’ private investment firm in 2006, where he eventually became Chief Information Officer.

- The MSX standard was formally discontinued in the early 1990s. But there have been a number of revival efforts, most recently MSXVR, a project that sells newly manufactured computers supposedly compatible with the original MSX standard.

- The Ampere WS 1 may have been the first clamshell-style laptop, beating Apple’s PowerBook G3 to market by about 15 years. But according to Old-Computers.com, the Ampere failed its FCC inspection and was thus never sold in the United States.

- Speaking of coming up with ideas that Apple later copied, the Seiko Epson RC-20 was the first true “smartwatch” in that it could run standalone programs. The watch had the same Z80 microprocessor used in the MSX standard.

- The end of the Apple Lisa would eventually lead to a mass burial of 2,700 machines in a Utah landfill sometime in September 1989, according to Tim Hall.

- For the record, Hitachi was not the world’s top-selling computer company by the year 2000. Compaq took that honor, at least according to Wikipedia. NEC was the only Japanese company to crack the top-five that year.

- As I pointed out in my post on the Atari 520ST, the real Japanese “invasion” came from video game consoles, notably the Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sega Genesis. The success of these purely video game systems–which didn’t require a keyboard at all–also likely helped to squash any potential interest in the MSX standard in the United States.