Computer Chronicles Revisited 38 — The Atari 520ST and Commodore 128

In my last post, I discussed Bill Gillis, then a Charles Schwab executive in charge of its technology division. Gillis came to Schwab from Mattel, the toy manufacturer best known for Barbie. In the early 1980s, Gillis oversaw Mattel’s efforts to compete in the video game console and low-cost computer markets with the Mattel Intellivision and the Mattel Aquarius, respectively. The Intellivision proved to be a modest success. The Aquarius, however, was such a bust that Mattel effectively pulled it off the market after just four months in 1984.

Mattel was far from the only company to exit the computer business in this period. Many of the small computer manufacturers profiled on Chronicles to this point–Vector Graphic, Morrow Designs, Osborne, and Gavilan to name a few–were dead or on their last legs by mid-1985. But those firms competed in the mid- to high-end business market. Mattel was in what was considered the “low-end computer” market, which was just another way of saying the sub-$1,000 home computer market. Here, too, there was a transition underway with many early players like Texas Instruments and Coleco (another toy company) folding up their tents.

Two low-end manufacturers that managed to survive this period were Atari Corporation and Commodore International. Unlike the business computer companies listed above, neither Commodore nor Atari started out making microcomputers. Nolan Bushnell co-founded the original Atari, Inc., in 1972 to develop coin-operated arcade machines. When Bushnell decided to adapt video game technology into a programmable home console–what became the Atari VCS a/k/a the Atari 2600–he needed more capital to make that happen. Conditions were not favorable in the mid-1970s for a public stock offering, so Bushnell opted for the next-best thing. He sold Atari to Warner Communications, a budding conglomerate run by Steve Ross. As a division of Warner, Atari not only successfully launched the VCS in 1977 but also an early line of inexpensive 8-bit microcomputers in 1979.

Commodore’s early history was even further removed from microcomputers. Jack Tramiel, a Polish immigrant and Holocaust survivor, learned to repair typewriters while serving in the U.S. Army. Tramiel and a partner started selling refurbished typewriters in New York City in the mid-1950s and eventually purchased a small shop in the Bronx. In 1958, Tramiel incorporated Commodore Portable Typewriter Limited to import typewriters from Czechoslovakia into Canada. Four years later, Tramiel changed the name to Commodore Business Machines and took the company public on the Montreal Stock Exchange. (The company was renamed again, this time to Commodore International, in 1976.)

In 1965, a major scandal involving the collapse of a Canadian finance company, Atlantic Acceptance Corporation Limited, nearly took down Tramiel and Commodore. The person at the center of the scandal was C.P. Morgan, who both controlled Atlantic Acceptance and served as chairman of Commodore. To make a long story short, Morgan was replaced as chairman by Irving Gould, who essentially bailed out Commodore and kept it going as its now-largest shareholder.

During the 1970s, Commodore entered the booming electronic calculator business. This led to Commodore acquiring MOS Technology, a Pennsylvania-based manufacturer of microprocessors. Chuck Peddle, the chief engineer at MOS Technology, told Tramiel that he was interested in building a personal computer. As Leonard Tramiel, one of Jack’s sons, recently recalled on his blog Vintage Computer Stories, “If Commodore wanted the product [Peddle] would do it as an employee. If they didn’t the[n] he would quit and do it on his own.”

Jack Tramiel decided to back the project and Peddle’s machine, the Commodore PET, debuted at Jim Warren’s first West Coast Computer Faire in 1977. The PET was the first in a hugely successful line of low-price, 8-bit microcomputers that later included the Commodore VIC-20 and the Commodore 64.

By the mid-1980s, Jack Tramiel was the undisputed “king of the low-cost computers,” as Stewart Cheifet would describe him in our next Chronicles episode. But that reign ended abruptly on January 13, 1984, when Tramiel resigned as Commodore’s chief executive. Barbara Wierzbicki, reporting on this historic event for InfoWorld, suggested Tramiel quit because Irving Gould wanted to bring in an outside executive to oversee Commodore’s international operations. Others said Gould thwarted Tramiel’s efforts to install his three sons as senior executives within the company. One former Commodore employee told Wierzbicki that Tramiel perhaps had “the wherewithal to realize that the company has grown too large to be managed” as a family business.

But this wasn’t the end of Tramiel’s story. Within a year of leaving Commodore, Tramiel ended up as owner and president of Atari. This wasn’t exactly the same Atari started by Nolan Bushnell. (Bushnell himself was long gone, having been fired in 1979 from his own company.) As discussed in a January 1985 Chronicles episode, the North American video game market essentially melted down in late 1983 and early 1984. This left Atari, which had once been Warner Communications’ most profitable division, suddenly dragging down the company’s stock price like an anchor. Desperate to stem the bleeding, Steve Ross basically gave away Atari’s home computer and video game console assets to a new company controlled by Tramiel. Tramiel paid no cash in the deal but instead assumed $240 million in long-term promissory notes. Tramiel then renamed his company Atari Corporation. (Warner retained Atari’s original coin-operated video game business under the name Atari Games, Inc.) Tramiel then poached a bunch of his loyal former employees from Commodore and also installed his sons in key executive posts, including Leonard Tramiel as vice president in charge of software.

The Increased Expectations of Home Computer Users

Jack and Leonard Tramiel were the featured guests of this episode. The formal subject was “low-end computers.” The Tramiels were there to show off the Atari 520ST, a machine already dubbed “the Jackintosh” by the press as Tramiel positioned the machine as a low-cost 16-bit alternative to the Apple Macintosh. Meanwhile, Stewart Cheifet also interviewed an executive with Tramiel’s former company, Commodore, about its own upcoming product, the Commodore 128.

The episode began with Cheifet standing in the aisle of a Toys “R” Us store in Redwood City, California. Cheifet quipped that computers were now just another item on the shelves of mass merchandisers. And while companies like Coleco, Mattel, Texas Instruments, and Sinclair had now exited the low-end computer business, Commodore and Atari were still battling it out in the “low-cost computer wars.”

In the studio, Cheifet and Kildall commiserated next to a Commodore VIC-20. Cheifet said this was the machine that really got the low-cost computer business started, allowing people to go out and buy a small computer for just a few hundred dollars. He noted that with all the talk about IBM and Apple, there were now more Commodores out there than any other computer. But now that Commodore and Atari were coming out with more sophisticated computers, did this mean the line was disappearing between so-called low-end computers and mid-range offerings from companies like Apple? Kildall said the “low-end” traditionally referred to the home market, and that meant pricing computers like television sets. Today, home consumers expected a lot more than they did a couple years ago. So success at the low end now required offering more sophisticated hardware and software systems.

Getting the Most Out of the C64

Robin Garthwait’s first remote segment focused on how people continued to make innovative use of existing low-end computers, specifically the Commodore 64 (C64). Over B-roll footage of a San Francisco music studio, Garthwait explained that musicians used a C64 program called Just Intonation as an “unconventional tuning system.” Unlike a traditional 12-tone scale, Just Intonation required re-tuning musical instruments to fit newer, simpler ratio intervals. The C64 could then generate a piece of music based on mathematical descriptions. There was no limit to the software’s tonal variations–just like a human singer–and re-tuning the software was much easier than re-tuning a piano. And while the C64’s sound quality restricted performance, Garthwait said the machine’s role was really more of a sketchpad to test new ideas, provide background sounds, and serve as a reference for tuning other instruments.

Garthwait then profiled another unnamed application that focused on the use of graphics in low-end computers. An unidentified man used a digitizing pad and color platter to painstakingly create a library of city maps, showing the locations of projected buildings and their shadows, traffic congestion, and land usage. Garthwait said these different maps could then be printed on transparent plastic, allowing the user to highlight certain aspects of each map and study them together in overlay.

“We Like to Sell to the Masses, Not the Classes”

The only round table for this episode featured Jack and Leonard Tramiel joining Cheifet and Kildall. (To make things easier, I’ll refer to each Tramiel by their first names.) Kildall opened by asking Jack to explain his approach to marketing low-cost computers. Jack said his goal was always to bring the best technology at the lowest prices: “We like to sell the masses, not to the classes,” he stated succinctly.

Kildall said Atari’s new 520ST posed a threat to mid-range computers–such as the Apple Macintosh–with a base price of $800 and featuring 512 KB of RAM, a 16-bit Motorola 68000 processor, and a monochrome display. How did Atari manage to hit that price point? Jack said that by knowing and understanding the semiconductor business, you could always foresee what you were able to come out with. He noted that when development started on the 520ST, 256 KB of RAM cost $30. Today it was down to just $4.

Kildall asked Jack–who famously produced his Commodore machines out of the MOS Technology factory in Pennsylvania–if the Atari machines were being built offshore. Jack conceded that the 520ST was assembled in Taiwan. But he said more than 75 percent of the parts were made in the United States and then shipped to Taiwan.

Cheifet asked for more information about the actual cost of building the ST. Jack said the assembly of the computer reflected about 2 percent of total price. Cheifet then asked Jack if his ability to guess where prices were going marked the difference between a successful product launch and companies like Coleco and Texas Instruments, which had recently exited the low-cost computer market. Jack noted that Coleco was a successful toy company, but it had failed by trying to apply that same technology to computers.

Kildall followed up, asking if where the computers were sold made a difference. Commodore famously sold the C64 in Kmart. Was that a good place to sell a computer? Jack noted that Kmart was a department store that sold a lot of high-end video and sound equipment. He believed that Atari’s customers were sophisticated enough to know the value of what they were getting–and they would try to get the best price at any retailer.

Kildall asked Jack if he planned to market the 520 ST as a business machine and if that would make sense if the computers were sold at Kmart. Jack retorted Atari was building computers for “personal use.” That’s why it was called a personal computer. It was up to the individual where he wanted to use the machine. They could keep it in their home, their office, their lab, or anywhere else. He didn’t dictate to the customer where they should use the computer.

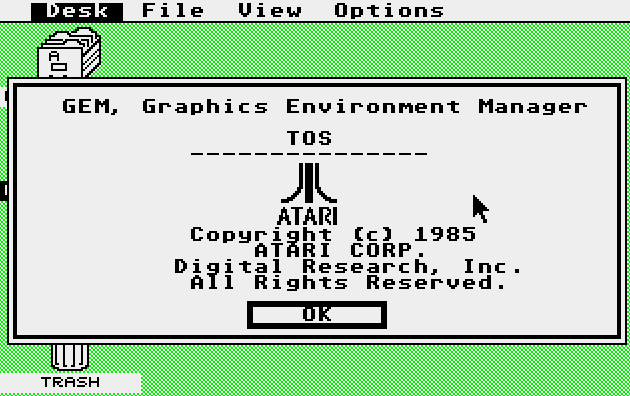

Cheifet asked Leonard to demonstrate a color version of the 520ST that was in the studio. Leonard showed off the operating system–which was Digital Research’s GEM graphical interface running on top of a custom kernel. (I’ve reproduced an image below using a modern Atari emulator.)

Cheifet observed that practically speaking, the ST looked like a color version of the Macintosh 512K. Leonard agreed with that comparison. Cheifet asked about the price. Leonard said the 520ST with a monochrome display and a single disk drive would retail for $800.

Kildall asked Jack for a rough guess on how many 520ST units he expected to sell. Jack said the market was softer in 1985 than it was in 1984 but he still believed they would sell 1 million computers this year.

Kildall then asked about the availability of software for a low-cost computer like the ST. Jack said he wasn’t concerned. He noted that at Commodore, there was initially little software available for the C64, but when he resigned the company was selling 300,000 machines a month. By that point, the C64 had one of the largest software libraries on the market. Kildall noted that it took some time for the C64 to reach that point. Could the process be accelerated with the 520ST? Jack said he thought the process would go faster this time because there were now more software companies that were writing programs for the Macintosh. And it would be easy enough to port software from the Macintosh to the 520ST, as they both used the same Motorola 68000 microprocessor. Indeed, Jack said there would be around 25 to 30 major pieces of software available for the 520ST at launch.

Cheifet asked about the competition for the 520ST. Was it Apple? Was it the new Commodore 128? Jack said everybody was competition as far as he was concerned. But specifically for the ST line, the main competitor was Apple. He hadn’t seen the Commodore 128 yet so he couldn’t say anything about it.

Kildall asked about potential competition from Japanese computer manufacturers. As far as the Japanese were concerned, Jack said, he “was able to keep those people out of the U.S. market and almost the world market for the past seven years.” He pointed out the Japanese never bothered to enter the 8-bit computer market and he didn’t expect them to enter the 16-bit market either. Jack said the reason the Japanese had been able to successfully compete in other U.S. markets, such as automobiles, was that in those industries there were substantial profit margins that gave Japanese manufacturers an opportunity to come in with quality products and still undercut U.S. producers on price. Jack said his approach was to start out by focusing on the best quality for the lowest price, and in doing so keeping that type of competition out. Kildall agreed the C64 was definitely a computer that kept the Japanese machines out of the U.S. market.

Commodore’s New Three-in-One Computer…and Its Secret Project

Stewart Cheifet opened the final segment with a remote report from Commodore’s headquarters in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He noted that while Commodore had put more personal computers into homes than anyone else, sales were starting to level off industry-wide. This put pressure on Commodore to come up with something new–the Commodore 128 (C128).

Frank Leonardi, a Commodore vice president, spoke with Cheifet about the C128. He said this new computer had twice the capacity and the features of the C64 while remaining totally compatible with the older machine. Cheifet explained in voice over that the C128 could operate in three different modes. It came standard with 128 KB of memory and could jump between an 80-column or 40-column display. There was even a mode to run Digital Research’s CP/M operating system.

Leonardi compared the C128 to the Apple IIc, the most recent revision to the Apple II line, which released a year earlier. He said the C128 had all of the same features and functions of the IIc, but because of Commodore’s high-volume, mass production capacity, it could still make a reasonable profit by selling the C128 at half the price of Apple’s machine.

Cheifet noted that if Commodore was able to lure away potential Apple buyers, it would mark a new kind of push into the already shaky personal computer market. But he added that the company once associated with action games and entry-level computers now had loftier goals, including a secretive project called “Amiga.” Leonardi said the forthcoming Amiga computer would offer expanded capabilities in terms of graphics, animation, and telecommunications. Commodore planned to position the Amiga as a computer for higher education and high-end homes. Leonardi said the Amiga might not be able to replace the IBM in Fortune 1000 companies, but it would offer a compelling alternative to the Macintosh.

Cheifet said that many “industry observers” remained skeptical about Commodore’s decision to enter the “mainstream” personal computer market, but Commodore itself was so confident that it planned to introduce a third new computer, a portable machine with a liquid-crystal display. The LCD machine would come with eight built-in programs, a modem, 32 KB of memory, and a 80-by-16 text display. Commodore had not yet set a price but said it would be “extremely competitive.”

Leonardi told Cheifet he wasn’t worried about personal computer sales leveling off. He said Commodore had yet to tap more than 15 percent of the market for microcomputers. Commodore had no viable competitors in the “mass market,” he said, so now Commodore was looking towards opening up other channels to strengthen their position and capture more market share in the long haul.

Wrapping up the segment from Commodore’s factory floor, Cheifet noted that one problem with buying a C64 or similar low-cost computer was the relative lack of support. Customers often purchased these machines at a discount retailer where the salesperson–if there was one–probably knew less about the computer than they did. For many low-end users, Cheifet said the solution to this lack of support was to join a user group. This led into a brief Robin Garthwait segment where she attended a meeting of the Marin Commodore Computer Club in California. There’s really nothing worth noting from this segment–it was basically just snippets of conversations with people attending the meeting–so let’s move back to the studio.

Atari Would Sell ST to “Whoever Has Money”

The round table with Jack and Leonard Tramiel continued. With respect to user groups, Gary Kildall said they were often associated with lower-quality software on the C64. Did the Tramiels think that was true? And did a low-cost computer need “good quality” software to be successful? Jack said he believed the software had to be good stuff. The consumer was more sophisticated today. They’d seen and understood more when it came to computers. Indeed, many people today had now had computers in their hands for the past eight years, dating back to when Commodore launched the PET. Consequently, these users were now demanding more.

Cheifet asked where Atari planned to sell the 520ST. He noted there was industry criticism when Tramiel decided to sell the Commodore 64 in Toys “R” Us and Kmart stores. Given the ST was a more sophisticated machine, what was Tramiel’s sales strategy going forward? Jack said that “whoever has money will be able to sell” the 520ST. He was looking for a very broad distribution. Specialized computer retailers served a certain purpose. They held the hands of business people and others who didn’t know how to operate a computer. But Atari was selling the ST to people who had knowledge–to the youth, as Jack put it. (Actually, he said “yute” like Joe Pesci in My Cousin Vinny.) Basically, anyone between the ages of 6 and 26 who were trained in school and were not strangers to computing. For that reason, Jack said the ST could be sold almost anywhere.

Kildall asked if there would be special training programs for retailers, like the store clerks in Kmart, who would be selling the machine. Jack said there would be training for both the people selling and buying the machine. The goal was to include programs on floppy disk that could be read right off the ST. Ideally, the computer would actually teach the owner how to use it.

Kildall asked Jack if he saw any difference between marketing computers for the home as opposed to business. And how would Atari make the ST successful in the home market? Jack replied the 520ST was a stronger product than the current IBM PC that was used in offices. By getting the ST into the hands of the yute (youth), they would grow up and hopefully buy Atari machines for the office in the future.

Kildall ended by asking if that meant Atari would focus on the educational market? Jack said there was no question that education was a very important market. He said Atari would have a number of different programs to market the ST to the schools. The ST was the future of the computing business–and it was important to teach the kids on today’s computers, not yesterday’s computers.

Would Atari Overtake Apple?

Paul Schindler’s closing commentary was essentially a commercial for Atari. He said the 520ST had the “potential to be the most exciting thing that’s happened to the computer since the Macintosh.” Jack Tramiel was the man who revolutionized the home computer–and Schindler believed Tramiel wold do the same for the office. Things had been calm in the business PC market since IBM cane in and set the price-performance standard. But Atari was now set to upset everyone’s apple cart with “more bang for less buck” than had ever been seen in the business computer market. And once Atari blasted through the business market, Schindler said the home market would be next.

And while IBM deserved to have its position in the market challenged, Schindler feared it would be Apple that would be most likely hurt by Atari’s ascendance.

Atari, Lotus Delay Product Releases While Apple Ends Employee Massage Perk

Stewart Cheifet presented “Random Access” for this episode, which took place in April 1985.

- A favorite recurring “Random Access” item: The IRS was still having computer trouble. This time, Cheifet said that ongoing software problems with the agency’s new $100 million computer system meant 10 million tax refunds were now behind schedule. But the good news was that if a taxpayer did not receive their refund by June, then the government would owe them interest.

- New Jersey’s Department of Criminal Justice was now using computers to help track down “welfare abuse.” Cheifet said convictions for welfare fraud in the Garden State had tripled since the new system was put in place, recovering almost $4 million for the state.

- In Reading, Pennsylvania, the U.S. Department of Agriculture launched an experimental program to replace traditional food stamps with new plastic cards that could be read by computers at grocery stores. The USDA said the system could save the government hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

- Lotus Development Corporation, the makers of Lotus 1-2-3, reached an agreement to buy Software Arts, the company behind VisiCalc.

- The 10th West Coast Computer Faire drew nearly 50,000 attendees. Cheifet said the most talked about item at the event was Covox’s Voice Master, which could translate human singing into musical notation.

- Cheifet also noted two other recent computer expos, Atlanta Softcon and the first Japanese COMDEX show. At COMDEX, Sony showed off its newest CD-ROM prototype, including a write-once disc system. There was also a “software on a credit card,” that used embedded ROM chips on a plastic card, so a user could carry an entire box of business software in their wallet.

- Paul Schindler provided his weekly software review, an integrated software package called Ability. Schindler approved of the software’s “nitwit simple” graphics package and lack of copy protection.

- In other Lotus news, the Lotus Jazz package for the Macintosh was delayed and now expected to ship at the end of May 1985. Meanwhile, the main subject of this episode, the Atari 520ST, would not be out this month as promised. Atari was now targeting a summer 1985 release.

- Cheifet said that according to a recent study, the average IBM PC owner purchased over $1,300 in software during their first use of ownership. At the other end of the market, another study from a New York-based research firm said that 1.5 million low-cost computers were thrown in the trash each year.

- The Holiday Inn Crowne Plaza chain said it would be putting AT&T 6300 computers in 10 of its hotels. Customers could use the computers for $30 per day.

- Stoneware, Inc., said it was dropping copy protection from its database program DB Master.

- As part of company-wide cutbacks, Apple said it would no longer offer free massages for members of the Macintosh team.

Atari’s Rush to Bring the ST to Market

If the Apple Macintosh was the most over-hyped personal computer of 1984, the Atari 520ST would win that same award for 1985. Indeed, the media’s description of the ST as the “Jackintosh” seemed to reflect a certain degree of media restlessness with Apple, as reflected in Paul Schindler’s comments, and the belief that Jack Tramiel would be able to easily replicate his prior success at Commodore with Atari.

It didn’t quite go that way. The ST was certainly not a failure in, say, the Mattel Aquarius sense. Indeed, Atari would go on to produce computers in the ST line for the next eight years or so. But Jack’s on-air prediction of 1 million units in the first year was pure hype. Actual initial sales were closer to 50,000.

One thing you don’t quite get from watching this Chronicles episode–and this may be partly because Gary Kildall’s company was involved in the product–was a sense of just how quickly Tramiel rushed the 520ST to market. Warner Communications made its deal with Tramiel to dump the Atari, Inc., assets in July 1984. Atari Corporation started shipping 520ST machines in July 1985, just one year later.

Indeed, when Byte first reviewed the 520ST in its January 1986 issue, it wasn’t even a review–it was “product description.” The prototype that Atari had sent out for review was incomplete. Specifically, Byte noted, “Atari has not yet completed its BASIC interpreter, and the operating system, TOS, remains unfinished.” As for what Byte did receive, the desktop was “less effective than the Macintosh’s, the keyboard has an awkward feel, and the current operating system makes it impossible to switch between high-resolution monochrome and low- or medium-resolution color without installing the other monitor and rebooting.”

Still, Byte said that even this unfinished 520ST left a “very favorable impression,” given that it offered the power of a Motorola 68000 microprocessor at a “most reasonable price.” Several months later, the final Byte review by Eric Jensen concluded the ST was a “very appealing machine in need of some further software development.”

Those software issues largely revolved around the operating system. Unlike Apple, which had spent years internally developing a custom system and user interface for what became the Macintosh, Jack Tramiel was the type of executive who wouldn’t pay to develop in-house what he could buy cheaply from someone else. As tech historian Jimmy Maher noted on his blog The Digital Antiquarian, Tramiel turned to Digital Research to build the system software for the ST “because they were willing to license both GEM and a CP/M layer to run underneath it fairly cheap.”

But the finished product did not actually run CP/M, as it was incompatible with the Motorola 68000. Instead, Atari programmers went to Digital Research and, as Maher described it, “managed in a scant few months to port enough of CP/M and GEM to the ST to give Atari something to show on the five prototype machines that Tramiel unveiled at [the winter Consumer Electronics Show] in Las Vegas that January [1985].” That CES demonstration, in turn, helped fuel all the “Jackintosh” hype leading into Jack’s Chronicles appearance a couple of months later.

In retrospect, Tramiel’s decision to tie the ST to Digital Research–a software company that was clearly in decline even by this point–was just one of many factors that kept the ST from being the “Apple-killer” that pundits like Paul Schindler predicted. The 520ST and its successors did establish a niche market as a gaming machine–and later in music production, thanks to an included MIDI port–but by 1990, Atari’s share of the personal computer market hovered around 3 percent, according to Ars Technica. That was just half of Apple’s share and not even a drop in the bucket when compared to the 84 percent of market then held by IBM PC clones running MS-DOS and Microsoft Windows.

I would also point to two other events in 1985 that likely crippled Atari’s plans for long-term success with the ST. The first was the release of Aldus’ Pagemaker 1.0 for the Macintosh in July 1985. Unlike the ill-fated Lotus Jazz, Pagemaker proved to be the Macintosh platform’s first “killer app.” Apple may not have been able to challenge IBM in the business market, but Pagemaker helped establish it as the standard for desktop publishing. This solidified Apple’s position in the mid-range market.

Meanwhile, in October 1985, Nintendo of America began the first sales of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)–ironically, an 8-bit console based on the same 6502 microprocessor produced by Commodore’s MOS Technology–in a test run in New York City. The NES went on to sell over 30 million units in North America. In doing so, it effectively obliterated what was left of the market for low-end, non-IBM compatibles like the Atari ST. (Keep in mind, Atari would continue to produce home video game consoles under Tramiel, including the Atari 7800 and the Atari Jaguar.) To add insult to injury, Jack Tramiel’s Atari would later file an antitrust lawsuit against Nintendo, alleging its business practices amounted to illegal monopolization. In 1992, a San Francisco jury returned a verdict in favor of Nintendo.

Commodore’s Post-Tramiel Transition Struggles

Commodore struggled to move beyond its successful 8-bit products, in large part because Jack Tramiel had failed to invest in new technologies as CEO. After Tramiel’s departure in January 1984, Commodore Chairman Irving Gould brought in Marshall F. Smith, a former steel industry executive, as CEO. According to a 2007 article by Jeremy Reimer for Ars Technica, Smith abruptly canceled the LCD portable computer project mentioned in this episode even though the product was poised to be a big hit:

Commodore took orders for 15,000 units of the machine just at the [1985 Winter Consumer Electronics Show] itself, and it looked like it would be a smash success. That was when the CEO of Tandy/Radio Shack took Marshall Smith aside and told him that there was no money in LCD computers. Smith not only canceled the machine, but sold off Commodore’s entire LCD development and manufacturing division, based solely on this dubious “advice” from his competition! Commodore had a chance to take an early lead in the emerging market of portable computers. Instead, the company would never produce a laptop again.

Smith was soon replaced by another new CEO, Thomas Rattigan, who decided to focus all of Commodore’s efforts on its Amiga division. The Amiga is referred to in this Chronicles episode as a “secret” project. Amiga started out as its own company, which had actually been founded by a disgruntled Atari, Inc., engineer back in 1982. I’ll delve more into Amiga in a future post, but suffice to say the company actually became the target of a protracted legal battle between Commodore and Tramiel’s Atari Corporation. Commodore acquired Amiga outright in 1984 and released the first Amiga-branded computer, the Amiga 1000, in July 1985.

As for the Commodore 128, it was effectively the last hurrah for the low-end 8-bit microcomputer market. It was designed as a dual home/office computer, as it could run the full library of existing Commodore 64 software, while a separate Z80 microprocessor enabled the C128 to run CP/M software. But as I noted above, CP/M was already in an irreversible decline by mid-1985, so it’s unlikely many people bought a C128 to use it as an office machine.

As Frank Leonardi’s comments to Stewart Cheifet suggested, the C128’s real value to Commodore was that it provided a transitional product to complete with the Apple IIc. Launched in 1984, the IIc basically took Steve Wozniak’s classic Apple II architecture and suffocated it inside of a Steve Jobs design. The result was somewhat underwhelming and Apple continued to sell far more of its earlier IIe product. For its part, the C128 went on to sell about 4 million units, less than one-quarter of the C64’s lifetime sales.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of April 30, 1985.

- Jack Tramiel passed away on April 8, 2012, at the age of 83. He retired from the computer industry after selling Atari Corporation in the mid-1990s and later became involved with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Leonard Tramiel also retired from the computer industry after the demise of Atari Corporation. Since the mid-1990s, he’s focused on promoting science education and has even served as a volunteer eighth-grade astronomy teacher.

- The Atari name is still in use today by Atari SA, a French holding company. This Atari can trace its roots back to Jack Tramiel’s Atari Corporation. Meanwhile, the Atari Games, Inc., created by Warner Communications following the 1984 split became defunct in 2003 after changing ownership several more times. If you want to hear the entire saga of the Atari brand name, I recommend episode 32 of They Create Worlds, a video game history podcast presented by Alex Smith and Jeff Daum.

- Frank Leonardi remained with Commodore as executive vice president of its business division until 1988. He would later serve as president and chief operating officer of Cardinal Technologies during the mid-1990s. Since 2002, Leonardi has owned and operated a real estate brokerage in California.

- The Atlantic Acceptance scandal that nearly killed Commodore back in its days as a Canadian corporation spawned one of the most comprehensive investigations in that country’s history. The final report, prepared by an Ontario judge, spanned four volumes and over 3,000 pages. You can find a portion of that report at the Internet Archive. There’s also a decent attempt at explaining Tramiel’s role in the scandal in a post by an individual identified as Zube, which is archived at the Wayback Machine.