Computer Chronicles Revisited 37 — The Equalizer, Computer Colorworks Digital Paintbrush System, AT&T UNIX PC, and GRID Compass 1101

In the early 1980s, there were two major antitrust settlements that significantly impacted the evolution of the computer industry. The first was the the U.S. Department of Justice’s decision to withdraw its long-running antitrust case against IBM, which began in 1969. That lawsuit focused on IBM’s dominance in the mainframe and minicomputer markets, and the government’s retreat helped clear the path for IBM to aggressively enter the microcomputer market with the IBM PC.

The second event, which also took place in 1982, was a consent decree resolving the DOJ’s antitrust lawsuit against AT&T, which began in the mid-1970s. The decree led to the breakup of the Bell System’s local telephone service monopoly. While regional companies would takeover the local service, AT&T would now focus exclusively on long distance telephone service.

One side effect of the Bell breakup was that it also freed AT&T from a restriction imposed by a prior 1956 consent decree that barred the company from selling computers and related products. This subject has been discussed in prior Computer Chronicles episodes, notably with respect to UNIX, the operating system initially developed at Bell Labs.

This next Chronicles episode from 1985 focuses on both IBM and AT&T as they attempt to take the next step in the evolution of the microcomputer market–communications. We’re still a decade away from anything resembling the modern Internet, so the focus here is more on how to integrate personal computers with the existing telephone system. We also start to see how other businesses are slowly dipping their toes in the water of consumer-level “online” services.

Computers and Telephones Living Together! Mass Hysteria!

Stewart Cheifet’s cold open features him driving on a local freeway–rather unsafely–while talking on a Motorola car phone. He explained that it was thanks to computers he could cary on this conversation. After all, the car phone relied on computers to “hand off” his conversation between various relay stations.

Back in the San Mateo studio, Cheifet showed Gary Kildall a small handheld terminal device with a wireless antenna that could access a minicomputer located in Washington, DC, and access information such as stock quotes. Kildall said this was a good example of how computers and communications complemented one another. Back in the days of computer timesharing, users had to share data through a single machine. Personal computers brought that data onto the individual desktop. And while a lot of that data, such as letters and spreadsheets, were personal, there were other forms of data–notably large databases and electronic mail–that were changing dynamically everyday. This was where communications was really important. It allowed the personal computer to get at this dynamically changing data, which could not be locally generated.

The Coming of “Intelligent Phones”

Robin Garthwait presented her first remote segment, which provided an overview of a pilot project underway in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, area–coincidentally, the location of one of Chronicles sponsoring PBS stations–as the first step in creating a national fiber optic network capable of transmitting up to 1.7 billion bits of data per second. Garthwait noted that was the equivalent of roughly 170,000 simultaneous voice conversations. The fiber network relied on lasers that transmitted the data as pulses representing the digital bits. Since there was no need to convert the digital signal to analog, Garthwait said the fibers could carry computer data just as easily as voice data.

As part of the Harrisburg project, Garthwait said customers could also choose some “remarkably intelligent phones.” For example, there was a phone attachment that featured a LCD readout, which identified and stored the numbers of incoming calls. There were also phones that could remember the last call you made, or one that you just missed. The fiber system could even trace and reject calls from people that you would rather avoid.

PC Owners Could Now Be Their Own Stockbroker

The first studio round table had William F. Gillis and Bob Metcalfe join Cheifet and Kildall. Metcalfe created the Ethernet computer networking standard while working at Xerox PARC and later co-founded 3Com Corporation to commercially develop the technology. Kildall asked Metcalfe if he saw any inherent limitations on using the “inherited” phone system to network computers. Metcalfe said that personal computers were getting smarter and smarter very quickly, and as they did they wanted to communicate more and more information. That was beginning to stress the 100-year-old telephone network. He added that while there was a lot of progress being made by the telecommunications companies to increase the amount of data they could handle, there were other potential means as well, such as cable television.

Cheifet asked Metcalfe to explain the importance of moving from an analog to a digital telephone system. Metcalfe said the transition, which began 10 to 15 years earlier, meant not only reducing costs but also providing communications that were more suitable for computer networking.

Cheifet then turned to Gillis, an executive with the Charles Schwab Corporation, a popular discount brokerage, to demonstrate an application that relied on computer communications to provide stock quotes. Gillis explained Schwab’s quote service made this information accessible from any touch-tone telephone, which he demonstrated with a phone hooked up in the studio. Essentially, this was an early example of a phone tree system. Cheifet described it as using the telephone as a kind of computer terminal to access another company’s database. Kildall asked if a customer could actually place a stock order with this phone service. Gillis said no.

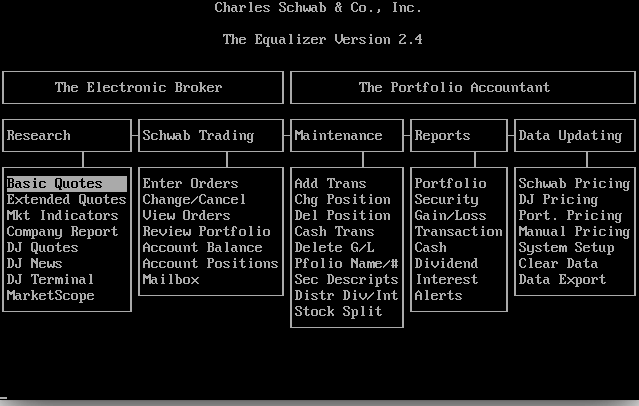

But Gillis then showed another, software-based product that did make it possible for users to trade stocks directly. This was called The Equalizer. Gillis said the software allowed you to not only buy and sell stocks, but also conduct research and maintain your overall portfolio. He demonstrated The Equalizer by using his own account to purchase some shares of Metcalfe’s 3Com Corporation. Cheifet said the software basically allowed you to act as your own broker. Gillis said that was correct. The user could format their orders locally–which saved on communications costs–before going online to check the current market price and execute the transaction. (Below is an image of the main menu of a later version of The Equalizer software released in 1991.)

Kildall said this was a good example of using local computing to prepare an order and then connecting to a bigger system to make a transaction that could not take place locally due to the need to access a larger database. Gillis added that there were thousands of stocks being traded, and that database would overload the capacity of most small computers.

Cheifet clarified that The Equalizer actually placed orders directly. Gillis said that was correct. The order was examined by a Schwab broker who then just had to hit “one key” to forward the customer’s order to the stock exchange.

Kildall asked Metcalfe where he saw technology like this going. Metcalfe reiterated his earlier point that as computers became smarter and smarter their appetite for information would also grow dramatically. In addition to databases, he said another area that would fuel this growth would be electronic mail.

Cheifet asked how much of an impact the breakup of AT&T and the subsequent deregulation–i.e., the lifting of the 1956 restrictions–would actually play a role in promoting computer communications. Metcalfe said the prior regulation tended to put a wet blanket on innovation. Now that a higher level of competition had been introduced, we could expect a higher turnover of new technology, particularly in the field of communications.

Kildall asked about alternatives to the telephone system, such as satellite. Could that ever take the place of the phone system for individual computer users as opposed to corporations? Metcalfe said there was some direct satellite communication to homes, but it would be some time before such technology would be practical on a larger scale, as you needed the ability for 2-way communication. There was a similar problem with using cable television. It was currently a 1-way system, but companies were looking into using it as a 2-way technology for computer networking.

Kildall concluded the segment by noting that the real challenge right now was simply to use the existing telephone system to its best advantage. Metcalfe agreed, pointing out the telephone infrastructure represented a vast investment that you didn’t want to just throw away.

“Millions of Islands of Computing That Must Be Linked Together”

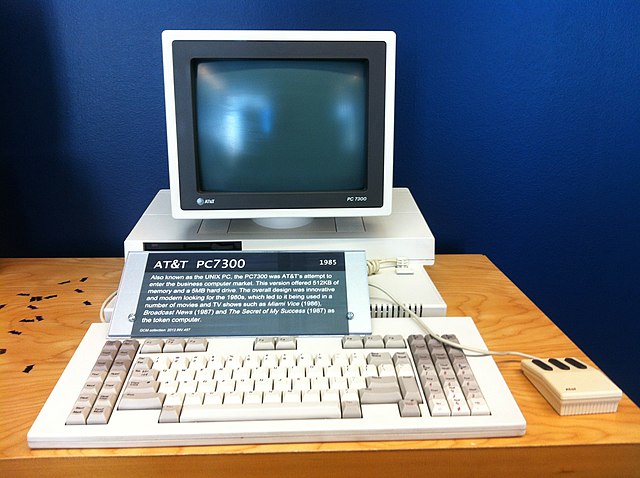

The next segment began with Stewart Cheifet narrating some B-roll footage of Bell Labs. Cheifet went to Bell to interview Steven Bauman, the executive director of AT&T Information Systems, about the company’s new PC 7300, also known as the UNIX PC. Cheifet said the 7300 represented a different approach from AT&T’s first computer products by relying on the company’s traditional strength in data transmission. The UNIX PC was specifically designed for multi-user, multi-tasking applications. It featured overlapping windows–similar to the Macintosh user interface–a UNIX operating systems, and a built-in telecommunications manager.

Bauman said the 7300 took the plain old telephone and hooked it into a machine such that the user could control who they were calling. For instance, when a telephone call came in, the user could pull up a history of their last five conversations with that same person.

Cheifet said the 7300’s “telephone with a memory” and electronic mail features were designed to interface with AT&T’s 1 MB data network, which provided fast, all-digital transformation of voice and data together. In that respect, AT&T’s UNIX PC replaced the need for a traditional computer modem. Bauman noted that UNIX was the “magic” that allowed the system to integrate communications with computers.

Cheifet noted that some computer watchers believed the next computer era would be a battle between AT&T and IBM. Bauman said he didn’t see it that way. IBM was a competitor, he said, but he saw AT&T as another American company that would help the industry prepare for the “real onslaught” that was coming from Japanese computer manufacturers.

On that point, Cheifet said there was a basic difference between how American and Japanese companies approached data distribution. While the Japanese gave higher priority to making mainframes more friendly, the United States took a more local approach. Bauman noted that Americans were fiercely independent and liked to be autonomous. That meant they wanted control over their data. This led to the creation of “millions of islands of computing that must be linked together.” Once we solved that problem, he said that other issues like user friendliness would be easier to address.

IBM Makes Its Own Move Into Communications

Meanwhile, IBM had taken steps to add communications to its computer expertise by acquiring ROLM Corporation, a leading manufacturer of telecommunications equipment. Robin Garthwait interviewed ROLM’s customer marketing manager, Joann Yates, about the merger of voice and data transmission. Yates said the goal was to make accessing data as easy as making a phone call. Right now, nobody had to think twice about picking up a phone and calling someone anywhere in the world. But it was much more difficult when you wanted to call any computer in the world. ROLM’s goal was to make it as simple as possible to do both without sacrificing one for the other.

Garthwait said products such as the ROLM Cedar, combined the capability of a personal computer with a highly developed telecommunications function. Yates said products like the Cedar were designed for the “communication-intensive knowledge worker” who could not afford to sacrifice their phone calls for their computer. The fact that PCs were becoming more commonplace and people wanted to to both things at once placed more pressure on the telecommunications industry to respond.

Online Graphics and Military-Grade Encryption

Back in the studio, Glenn Albinger and Barry Margerum joined Cheifet and Kildall. Albinger, the director of software systems for The Computer Colorworks, demonstrated his company’s product, the Digital Paintbrush System. This was an early example of software that could actually transmit bitmap images over telephone lines. Albinger linked the computer in the studio to his company’s computer in Sausalito (about 30 miles away). The Sausalito computer loaded a map of the area drawn using the Paintbrush software and transmitted it to the studio computer (see image below). Albinger noted you could not talk on the phone and transmit the picture at the same time.

Cheifet turned to Margerum, a vice president with Grid Systems, and asked about the concern some people might have with the security of data sent over telephone lines. Margerum noted his own company’s product, the GRiD Compass line of portable computers, recently incorporated “high-grade embedded encryption” as a standard feature. This meant the user could transmit data by telephone lines, satellite, or even microwave encrypted, so if the data were intercepted it couldn’t be exploited. Margerum then provided a brief demo using two Compass machines hooked up locally.

Kildall noted the obvious military applications for this encryption technology. Would encryption eventually make its way into the business market? Margerum said absolutely. The military was probably the area that had the most concern over data privacy. Civilian government agencies were also concerned. And the commercial world was the next market to look at, although Margerum said businesses haven’t seen the need to spend their money in that area. He thought when a “major catastrophe” happened, they’ll realize that their information was available to those who want it.

Cheifet asked about the practical uses for a machine like the Compass. Margerum said it was a portable, solid-state machine with no moving parts. It could take a 42-inch drop and still work effectively. So from a military standpoint, because it was powerful, lightweight, and had built-in communications protocols, it was an ideal system for field use.

Was Any of This Necessary?

Paul Schindler’s closing commentary lamented that there were a lot of things that would be possible with communications and computers that weren’t necessary but would be done anyway. For example, there will be more and more electronic mail even though some people would wish letters weren’t delivered so fast. Basically, nobody was answering the question if any of this communications technology was necessary or practical. He said the U.S. could follow the example of France, which was making more “sensible” use of technology by replacing their printed telephone books with computer terminals.

Compaq, Texas Instruments Announce New Machines

Susan Bimba presented this week’s “Random Access” segment, which dates the episode around March-April 1985.

- Compaq jumped into the computer-telephone market with six new products, including a new line of IBM compatibles called the TC-2500 telecomputer.

- Texas Instruments announced a new IBM PC-AT compatible called the Business Pro. The TI machine would come standard with 512 KB of RAM and a single 5.25-inch floppy disk drive for $4,000. Bimba said TI expected these new machines to double the company’s current 1 percent market share.

- National Semiconductor announced two new products designed to compete with IBM’s Sierra line of mainframes.

- Gene Amdahl’s Trilogy Limited, which recently abandoned efforts to develop a new supercomputer, acquired Elxsi for $64 million, which as Bimba noted had developed a supercomputer but lacked capital.

- Boeing Computer Services–a subsidiary of the famous aircraft manufacturer–recently released Boeing Calc–a commercial spreadsheet program that relied on online storage rather than local memory. Bimba said Boeing’s software was “truly three dimensional” and could store up to 1,000 pages.

- Paul Schindler reviewed Higgins, a $400 desk organizer program published by Conectic Systems, Inc., in Portland, Oregon.

- Bimba said Silicon Valley companies were now making efforts to clean up the industry’s reputation for encouraging and tolerating cocaine use. One unidentified company had gone so far as to fund an undercover police investigation of its own plant.

- The Handley School for the Blind in Illinois developed a new braille computer that can print 400 Braille characters per second, up to 600 lines per minute. Bimba noted that a Braille textbook that once took a full year to produce could now be ready in just a few weeks.

- Rohm and Haas, a Pennsylvania manufacturer, recently received a $46,806.37 tax penalty after it shorted the IRS 10 cents on $4.5 million in tax deposits made during 1983.

The Many Professional Lives of Bob Metcalfe

Although he’s not the focus of this episode, Robert Metcalfe is probably the most well-known of the guests. As previously noted, Metcalfe developed Ethernet and co-founded 3Com. But he left the company abruptly in 1990 after the board of directors passed him over for the CEO position in favor of Eric Benhamou. In a 1998 Wired profile, Metcalfe told writer Scott Kirsner that he was still smarting over the snub:

“Benhamou is a nerd who can’t give a presentation,” says Metcalfe, still irritated eight years after the fact. “He’s not horrible, but he’s not charismatic.” But Metcalfe acknowledges that it was Benhamou, not he, who won 3Com entry into the Fortune 500 and grew it into a US$5 billion powerhouse. “I’ve learned watching him that you don’t have to be charismatic to be a great CEO. To this day, he doesn’t have a charismatic bone in his body.”

Metcalfe, by contrast, is a cauldron of charisma. He is tough and charming, a persuader who knows how to listen, a provocateur who miraculously avoids making too many enemies. That combination of qualities made Ethernet a networking standard (today, it connects more than 100 million computers) and enabled Metcalfe to raise the first million dollars to launch 3Com.

About a year after leaving 3Com, Metcalfe decided to join the media himself, taking over as the publisher of InfoWorld, where he also wrote a weekly column. Metcalfe continued as an executive and columnist with IDG, the parent company of InfoWorld, until 2000. He then spent a decade in venture capital before transitioning into academia. Just recently, Metcalfe announced he would be stepping down from his position at the University of Texas-Austin, where he’s been an endowed professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering since 2011.

Gillis Clashed With Schwab “Culture”

The other guest I want to single out here is William F. Gillis. He began his career in marketing with RCA’s consumer electronics division in the 1970s before moving to jobs at AT&T and Western Electric. In 1981, Gillis joined the toy company Mattel to oversee its home computer division, which produced the ill-fated Intellivision video game console and Aquarius home computer.

It was in 1983 that Charles Schwab recruited Gillis away from Mattel to run its new Schwab Technology Services division. In his book about the history of Charles Schwab, author John Kador said Chuck Schwab himself told Gillis, “We are running this division as an entrepreneurial start-up. I want you to develop products and services to help individual investors make better investment decisions.”

The relationship later soured, however, and Gillis left the company a few years later. In his autobiography, Schwab himself recalled, “We brought in a brilliant guy named Bill Gillis to head Schwab Technology, but with a ‘my way or the highway’ approach, he eventually clashed and left.” Kandor offered a more nuanced take on what transpired:

Gillis was a supremely talented manager. In the software development industry where most projects are late and over budget, Gillis delivered the goods. Gillis could have written his own ticket at Schwab. But he made a classic mistake to which technologists are prone: He overstated and in doing so he violated a key piece of Schwab culture. In response to a question, Gillis announced that Schwab expected to sell 50,000 SchwabQuotes subscriptions. Chuck was aghast. Schwab people simply didn’t make such projections.

I would also point out here that Gillis is African-American. Indeed, he’s as far as I can tell the first African-American to appear as a guest on Chronicles. And as Kandor noted, he was also one of the “few African-American executives” in Charles Schwab’s history.

Fortunately, Gillis went on to have a long and successful career after Schwab. He served as president or CEO for a number of companies, including US West Enhanced Services, Motorola INFO Enterprises, and Parent Care, Inc., the latter of which he co-founded in 2003. Gillis also continues to work as a consultant in the industry.

UNIX PC Proved a Flop Despite Quality

As for the products featured in this episode, the AT&T UNIX PC was probably the most notable in the sense of being a commercial failure. According to one report from July 1987:

The 68010-based Unix PC or PC7300 developed and manufactured for AT&T by Convergent Inc has proved to be such a commercial disaster that the machine is now going out at fire sale prices in the US, leading observers to conclude that Convergent must have sold its excess stocks of the machine as a job lot to a third party. The machine is currently available at $1,900 for a 2Mb processor with 67Mb disk drive, documentation and extras, compared with about $5,400 list. The MS-DOS coprocessor is $140, down from $700.

That’s not to say that the 7300 was a bad computer. It reviewed quite well. Alastair J. W. Mayer, writing for Byte in May 1986, said it was “an excellent machine.” He cited the computer’s overall reliability, solid library of included software, and communications capabilities as key features. Mayer’s main criticism was the lack of color graphics, especially given the machine’s high sticker price. But he said it was still worth it given the PC 7300 came with a fast hard disk drive.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast data of April 2, 1985. Based on a computer display seen in one of the studio demos, the recording date was apparently March 9, 1985.

- Joann Yates remained with ROLM Corporation as its marketing manager until 1991. She later spent many years as a senior marketing manager with Sun Microsystems. She is currently retired and living in California.

- Barry Margerum was Grid Systems vice president of defense industry marketing from 1980 to 1988. Before that he’d worked at IBM and Apple. After leaving Grid, Margerum served as CEO at MITEM Corporation, an enterprise software company, and later at Euphonix, Inc., a high-end audio equipment manufacturer. Between 1993 and 2017 Margerum primarily worked for Plantronics (now known as Poly), another high-end audio equipment manufacturer. Currently, Margerum is an “angel investor” who provides seed funding to tech startups.

- I don’t have anything to report regarding the post-Chronicles activities of Steven Bauman or Glenn Albinger.

- The Computer Colorworks was owned by Jandel Corporation, which dissolved in 2003. According to an August 1984 InfoWorld article, Digital Paintbrush initially sold for Apple II systems for $299 and was essentially marketed as a low-cost alternative to the Apple Graphics Tablet, which cost around $800.

- The ROLM corporation was so named because it incorporated the first letters of the last names of the company’s four founders (Richeson, Oshman, Lowenstern, and Maxfield). According to a 2018 Medium article by Wayne Beck, the ROLM founders started their company in 1969 before deciding on a product line. They eventually settled on creating portable computers for the military (similar to GRiD Systems). But ROLM later diversified into computerized telephone switching systems, which eventually became its main product. IBM purchased a 23 percent share of ROLM in 1982 before acquiring it outright in 1984. Just five years later, IBM sold its ROLM division to Siemens AG, which kept producing products under the ROLM name until the mid-1990s.

- John Ellenby, a British businessman, started Grid Systems Corporation in 1979. The GrID Compass was the company’s signature product line. As Allison Marsh explained in a May 2020 article for IEEE Spectrum, the 10-pound Compass was the first portable computer with a “clamshell design, in which the monitor folded down over the keyboard.” The machine cost $8,150 when it released in 1982, but it did come with a host of built-in business software and a 1200-baud modem. The Compass gained fame as “NASA’s original laptop” for use in space shuttle missions. Ellenby sold Grid Systems to Tandy Corporation in March 1988 in an all-stock deal. Grid continued as a subsidiary under Tandy. AST Research, Inc., subsequently acquired Tandy’s computer manufacturing operations in March 1993 for $175 million. AST shut down the Grid division but the name was purchased by a group of former managers, who formed a new company under the name GRiD Defence Systems, which still exists today.

- Paul Schindler’s reference to the French was specifically about the Minitel, an online service introduced throughout France in 1982, which relied on distributing free computer terminals to telephone customers. The Minitel will be featured in a later Chronicles episode.

- Perhaps confirming (the person) Charles Schwab’s disdain for bold projections of product sales, Bill Gillis had told the press while at Mattel in 1983 that the Aquarius computer would sell a “minimum” of 200,000 units and claim a 5 percent market share, according to The Dot Eaters, a video game history website. Mattel reportedly sold less than 8,000 units and pulled the machine from the market four months later, by which time Gillis had already left for Schwab.

- I wonder if Charles Schwab ever advertised The Equalizer on the television series of the same name, which premiered on CBS in September 1985.

- The image of the AT&T PC 7300 used above is by Lee Leblanc for the Goodwill Computer Museum and is used here under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.