Computer Chronicles Revisited 33 — Steve Boros, Sportspak, CompuTennis CT120, and the Converse Biomechanics Lab

Michael Lewis’ 2003 book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game described Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane’s use of advanced statistical analysis–known as sabermetrics–to build his team. The book was later turned into a film, which only further cemented the popular notion that Beane was the key figure in marrying computer-aided statistical research to the 19th century pastoral game.

Beane’s tenure as general manager did not begin until 1997. Nearly 15 years earlier, there was another important figure in the Oakland baseball hierarchy who served as a champion for using “computers in the dugout.” That was Steve Boros, a former third baseman who served as the A’s field manager during 1983 and part of 1984. After Oakland fired Boros mid-season, he joined the San Diego Padres front office and later served as their manager in 1986. During his front office stint in San Diego, Boros was also a guest on a March 1985 Computer Chronicles episode, where he discussed the role computers could–and should–play in baseball.

The episode’s overall subject was “computers in sports.” Stewart Cheifet delivered his cold open from a tennis court. He noted that in tennis, the human brain had to perform thousands of calculations per second to tell the body what to do. But now, tennis players and coaches were turning to computers to discover the secrets to peak performance. Could a computer help you play a better tennis game?

Back in the studio, the computer certainly wasn’t helping Cheifet and Kildall as they struggled to keep up with a table tennis-playing robot produced by Sitco Robots. Cheifet said there were about 3,000 of these robots currently in use to train tournament ping pong players. Yet the number crunching of a computer and the finesse of an athlete seemed like totally opposed concepts. Cheifet asked Kildall for more clarification on the role of computers in sports. Kildall replied that sports represented just another vertical market–i.e., another place to sell computer systems for use in analyzing statistics, trends, strategies, and even to help design equipment.

SkyCam Turns Playing Fields into 3D Games

Wendy Woods presented her first remote report, which featured B-roll of footage taken in various stadiums and arenas using SkyCam, a new computer-controlled camera that was “transforming the art of televised sports.” Woods said the SkyCam could glide and dive, shoot straight up in the air, and hover silently within inches from the ground. The system was supported on four thin cables strung across the field, while the camera sat in a dumbbell-shaped cradle equipped with gyroscopic stabilizers and radio-controlled electronics. The SkyCam operator used a joystick to direct the camera’s position almost anywhere on the field–and at speeds of up to 27 miles per hour.

Woods said SkyCam was basically an exercise in geometry, giving the television director precise and instant control over what used to be the most difficult part of shooting a sporting event. Since the positions were defined in the computer, the camera’s moves were choreographed in advance and stored in memory for later replay. And while SkyCam’s uses were not limited to sports, Woods said such events made the best use of the system’s capabilities. A rectangular playing field was easily broken up into X-Y coordinates for positioning the camera. Essentially, Woods said the field became a vast 3D computer game with a range of about 1,000 square feet and several hundred feet high. But unlike the typically flat images of a video game, SkyCam promised an almost infinite variation of depth and angle.

MLB, NFL Coaches Learn to Integrate Computers Into Scouting and Strategy

Joining Cheifet and Kildall on-set for the first of three roundtables this episode was Billy Hicks and the aforementioned Steve Boros. Kildall noted that in the past baseball managers manually gathered game statistics to help decide strategy. But during his tenure in Oakland, Boros automated this process with the help of computers. How did he do that? Boros said that what he tried to do was use the computer to keep track of certain matchups–i.e., Oakland’s hitters versus the opposing team’s pitchers, and vice versa.

Boros cited the example of a May 12, 1983, game between the A’s and the Detroit Tigers. Prior to the game, Boros said he was thinking about moving center fielder Dwayne Murphy down from his “cleanup” spot batting fourth in the lineup, as he had been struggling to hit recently. But after reviewing a computer-generated report, Boros noticed that Murphy had gone 8-for-16 against Detroit starting pitcher Dan Petry. So Boros decided to leave Murphy batting cleanup, and in the fifth inning he hit a grand slam, which helped propel Oakland to an 11-4 victory.

Boros added that now that he was with San Diego as its director of minor league instruction, he would push the club to adopt Oakland’s practice of using computers to keep track of scouting reports on prospects. He said that at the major-league level, he also thought it was a good idea for managers to not only track matchups, but also where in the strike zone a player was likely to strike out or hit a home run, as well as where he would likely hit a ball into the field so as to make it easier to reposition defensive players.

Cheifet asked Boros if he actually used a computer during the game. Boros said he used to look at the computer reports on matchups before the game and take down notes that he would keep in his pocket. But you could not actually have a computer with a monitor in the dugout. This violated Major League Baseball rules, as such a setup could also be used to steal signs from the opposing team’s catcher.

Cheifet asked what management thought about the use of computers in this way. Boros said they were a little bit resistant. He cited Oakland management as a “little more progressive” in this area. He added that there were younger team owners, such as the Atlanta Braves’ Ted Turner and the New York Yankees’ George Steinbrenner, who were embracing computers. But a lot of people in baseball were conservative and resistant to such new ideas.

Cheifet asked if there was ever a situation where Boros’ gun instinct told him to “do it this way” and the computer advised him differently. In such cases, Boros said he always went with his instinct. A manager had to be a master psychologist, he said, and that meant sometimes throwing out the computer data because it was bad psychology and you didn’t want to destroy the confidence of a player.

Cheifet then turned to Hicks, a customer support manager with MDS Qantel, which produced Sportspak, a computer system designed to facilitate statistical analysis in sports. Specifically, Cheifet wanted to know how football coaches used the system. Hicks said Sportspak was primarily used for scouting reports, tendency reporting, and game analysis. For instance, a coach wants to know what the other coach is likely to do in a 3rd-and-2 situation between the 40- and 50-yard lines. What were the tendencies? Would the coach run the ball right or left, or would he call for a pass?

Kildall asked if Sportspak could be used during an actual game. Hicks said no. Like Major League Baseball, the National Football League did not allow computers on the sidelines. You could have computers up in the press box to keep statistics, but that information could not be communicated down to the field. Hicks added that Sportspak was popular enough that opposing NFL teams in the same game often used the system to analyze one another.

Cheifet asked if Sportspak was also used at the college and high school sports levels. Hicks said yes, there were 19 major colleges using the system, mostly for football scouting reports. The system actually had three separate “modules”: sports, tickets, and accounting. This meant Sportspak was also used by the front office and ticket agents as well as coaches and athletic trainers.

Kildall asked about the exact hardware used to implement Sportspak. Hicks said it was a minicomputer manufactured by Qantel. There were three different sizes available and they included up to 128 terminals each.

Turning back to Boros, Cheifet asked if he was using a microcomputer when he worked for the A’s. Boros said yes, he used an Apple II. The Athletics’ director of sports information, Jay Alves, would input information during the game and help prepare the actual reports.

Keeping Track of Tennis Stats Courtside

The second roundtable featured Rich Anderson and Bruce Brown. Anderson, a former junior tennis coach turned computer science teacher, was there to discuss the CompuTennis CT120. Basically, this was tennis-based statistical analysis software that ran on an Epson HX-20 laptop connected to a Compaq Portable. Anderson described the setup as a “computer-age solution to a problem” that tennis coaches had been dealing with for a long time, namely keeping accurate data and statistics during a match. Typically, Anderson said coaches would simply take down notes on a piece of paper. But with CompuTennis, a scorer could take information down directly on the HX-20 and later upload it to the Compaq to perform a more detailed analysis. Since the HX-20 operated off of batteries, it was portable enough to carry onto the court.

Cheifet asked Brown, the scorer for Stanford University’s tennis team, to elaborate further on this. Brown said it was impossible to enter all of the shots made during a match, so he would simply input up certain key shots, up to nine for every point. Anderson added that once the data was loaded into the Compaq, the CompuTennis software could prepare a detailed analysis of the match that was useful for scouting an opponent.

Anderson then demonstrated a sample report taken from a December 1984 match in the Davis Cup final between John McEnroe of the United States and Henrik Sundstrom of Sweden. McEnroe lost the match in an upset. Anderson showed a CompuTennis report that explained McEnroe was having a bad serving day and that was a major factor in his defeat.

Kildall asked how the CT120 would actually be used courtside during a match. Brown said the coach could come up and ask for the latest statistics during the match, as the system could be updated to the last point played. The coach could then ask a question like, “Is the opponent making more errors off the forehand or backhand?”, and Brown said he could provide an immediate answer.

Computer-Aided Sailboat Design

Shifting gears–or rather, sails–Wendy Woods returned with her second remote feature, this time from North Sails in Berkeley, California. North Sails, a worldwide franchise of sail manufacturers, used an MS-DOS computer to perform what Woods described as the “normally time-consuming job of number crunching” to design the perfect sail for each boat. This computer then transferred those calculations to a second computer, which in turn communicated it to an X-Y plotter that marked and cut the plastic sails.

Larry Herbig, a designer with North Sails, told Woods that it was easy to get hung up on the numbers when making sails. So if you could deal with just the broad concepts and leave the computer to do the number crunching, it made things a lot easier and let him deal with more important things. Woods noted these “important things” included the stretch, shape, and strength of a sail. Those decisions were still made by human designers. The computer was simply there to reduce the labor cost and the tedium–and ultimately, help reduce prices for consumers.

Ultimately, Woods said the success of these computer-designed sails could only be judged in the actual sailing. On that score, Woods noted that North Sails’ sails had already won their sailboat owners many prestigious awards, including the 1983 America’s Cup (won by Australia II).

Building a Better Athletic Shoe

For the third and final studio roundtable, Jeff Cohen and Rick Bunch joined Cheifet and Kildall. Cohen and Bunch worked for Converse’s Biomechanics Lab. Cheifet asked about the lab’s work. Bunch said it was a general sports research facility that supported the development of athletic shoes. They were interested in how an athlete’s foot interacted with the footwear and how the shoe affected overall athletic performance.

Cheifet asked how computers helped with that goal. Bunch showed Cheifet an instrument that interfaced with a computer to collect data on how the pressure distribution evolved beneath the athlete’s heel and the shoe. The plan was to put the device directly into the heel. He said this were 24 elements (akin to sensors) on this prototype, but they also had a larger 128-element prototype.

Kildall asked if this type of device could eventually make it to the retail level so a customer could find the right kind of shoe. Bunch said it could be easily used for that purpose. More precisely, it would help fine-tune how much cushioning there needed to be in the rear or forward part of the shoe.

Cohen then sat in front of a personal computer hooked up to both a monitor and a small television set. He called up a sample graph taken from a test subject who was outfitted with the 128-element mat. Bunch explained the graph itself showed the measurements of the heel coming into contact with the ground as the subject walked from left to right. Bunch said this data could be used to measure a custom shoe for this particular subject. Alternatively, data taken from a quantity of athletes could be used to build an “average profile” to determine the appropriate amount of cushioning for shoes produced in mass quantity.

Cheifet asked about another device used by the Lab to study what it called pronation. Bunch said this measured a person’s rear-foot control. He explained that rear-foot control injuries were the number-one injury experienced by runners. This type of injury accumulated over thousands of miles spent running or training.

Cohen then showed a demo on the television of a person running on a treadmill. He said the computer sampled this video at a 30 Hz frame rate and saved it into memory. Bunch said these stored images were then analyzed to determine the pronation, which he defined as the angle at which the lower leg intersected the heel. He explained that a runner tends to experience rear-foot control problems at angles between 17 and 20 degrees. To correct this, the athlete required a shoe with a maximum level of support. He said a normal range of motion was around 7 to 9 degrees. The athlete in the video had a pronation of 12.9 degrees, indicating the need for a “moderate level of support.”

A Luddite Note of Caution

In his closing commentary, Paul Schindler pushed back at the idea of expanding the use of computers in sports. Noting that the San Francisco 49ers and Miami Dolphins both relied upon computer analysis during their recent Super Bowl, Schindler nevertheless “wanted to sound a somewhat Luddite note of caution.” He lamented that computers already told us what to do too much of the time. Sports were supposed to be a refuge. And while he understood that professional sports had not been pure for a long time, he still thought we should take a stand of, “Computers out of sports! Athletics for the people!”

DEC, Convergent Pull the Plug on Failed Personal Computers

Stewart Cheifet presented “Random Access,” which is dated around March 1985.

- A high school student in California became the first person charged with “computer trespass” under a new California law. Cheifet said the teenager tried to break into a Stanford University computer that stored the grades for his high school class. His plan was to then charge his classmates $100 to change their grades. But this was thwarted after Stanford alerted local police to the fact someone had made 500 attempts to login to their system using the wrong password.

- IBM said it would soon have its own 1 MB memory chip ready to compete with an expected Japanese chip. Cheifet said the IBM chip would reportedly be twice as fast.

- Digital Equipment Corporation said it would end production of its Rainbow PC line. But DEC said it wasn’t giving up on microcomputers; it planned to release a new PC called the MicroVAX II.

- Meanwhile, another failed computer–the Convergent Technologies WorkSlate–was headed for the auction block. Cheifet said the portable computers, originally introduced at $1,200, would likely fetch just $200 apiece at auction.

- Paul Schindler presented his weekly software review. This week’s subject was ExecuTime, a $50 calendar program sold by Advanced Productivity Software. Schindler said he’s buy the program “just because it could handle multiple calendars at the same time,” allowing one secretary to schedule three different people.

- VersaTron announced its newest product, the Foot Mouse, which is exactly what it is sounds like.

- A new Macintosh program called FileVision offered a visual database that allowed users to store and retrieve data using pictures rather than words or numbers.

- IBM was offering a new $1,000 add-on for the PC called Watson, a combined hardware-software package that functioned as a digitized answering machine with digitized speech.

- A cosmetics company, Elizabeth Arden, was now using a computer–called “Elizabeth”–to help women shop for makeup. The machine captured a still-frame photo of a customer. The operator then applied various cosmetics to the photo electronically. When the customer was satisfied, the operator printed out the image with a list of cosmetics to purchase.

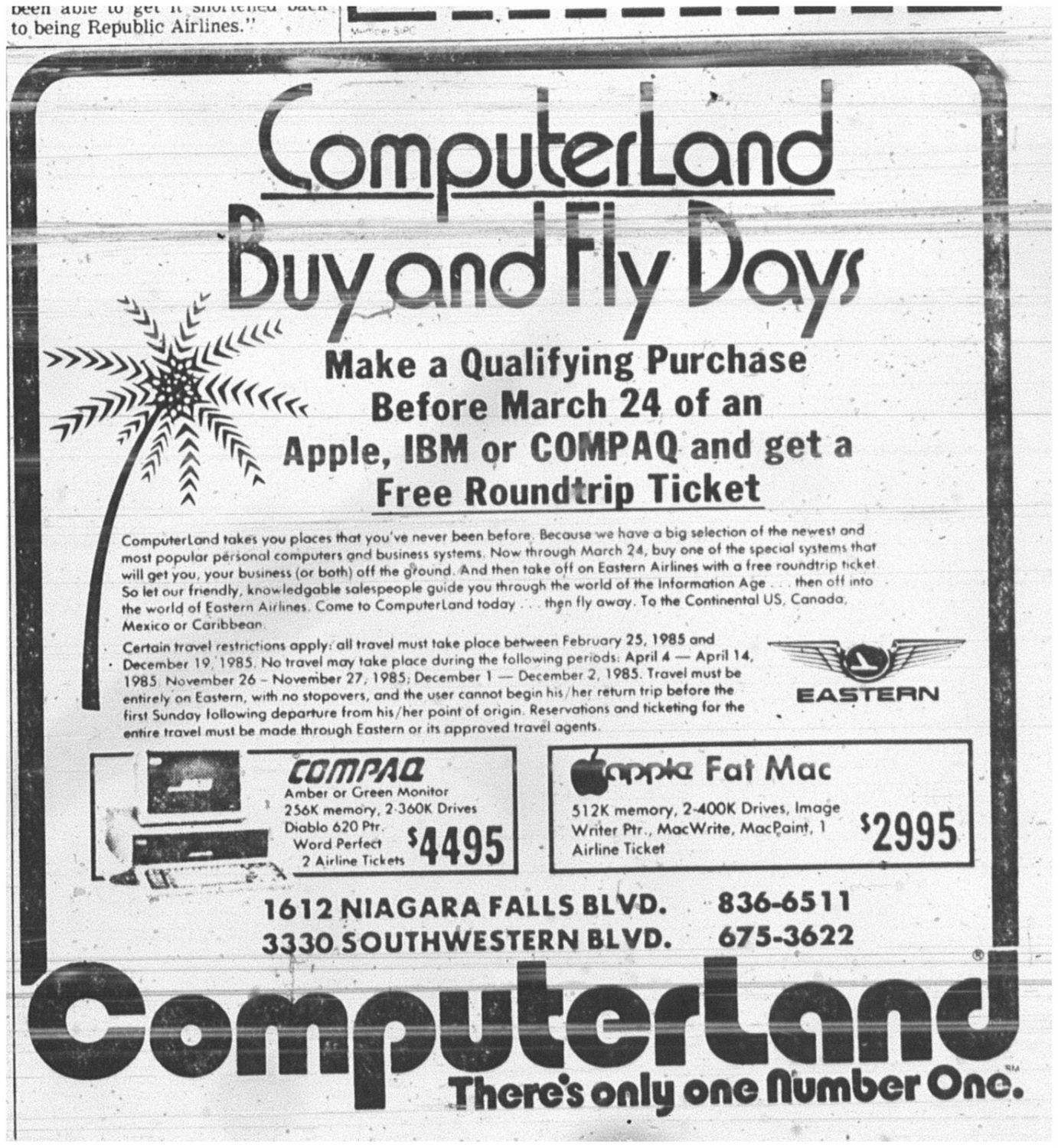

- ComputerLand was now offering a free round-trip on Eastern Airlines with the purchase of a new computer. As Cheifet quipped, “It sure beats Flight Simulator.”

Steve Boros (1936 - 2010)

Stephen Boros, Jr., was the oldest of five children born to Hungarian immigrant parents. He played college baseball at the University of Michigan. After being named an All-Big Ten third basemen in 1957, he accepted a $25,000 offer to sign with the Detroit Tigers while he was still in school. (Boros later finished his degree in English.)

Boros went on to play parts of seven Major League seasons with the Tigers, Chicago Cubs, and Cincinnati Reds between 1957 and 1965. Boros transitioned to coaching in the late 1960s, scoring his first managerial assignment with a Kansas City Royals’ affiliate in Waterloo, Iowa, in 1970. While serving as first base coach for the Montreal Expos in 1982, Boros received a call from the Oakland Athletics to interview for their vacant manager’s job.

Ray Kennedy, writing for Sports Illustrated in June 1983, said one of Boros’ first questions when he interviewed with Oakland ownership was, “Will I have access to a computer?”:

Boros got the job and the computer and has since been busily poring over all manner of printouts. The results? Well, it’s probably no coincidence that the A’s have been unexpected contenders in the American League West this year. For one thing, Boros says, the machine has proved an invaluable scouting tool for a rookie manager. “Otherwise,” he says, “I’d have had to go around the league at least once to get a line on players. Now I have all the information at my fingertips based on pitch-by-pitch data from the ‘81 and ‘82 seasons.”

Kennedy noted that Boros was not the only “convert” to the “religion of mathematical probabilities as dictated by the magic machine.” White Sox manager Tony LaRussa used a similar system in Chicago. Kennedy also explained that while both managers used an Apple II computer to enter information, the data was later “fed via telephone lines into a mainframe Digital Equipment Corp. computer in Philadelphia.” The mainframe then prepared the reports and sent them back to the managers before their next game.

Oakland finished the 1983 season with a 74-88 record, fourth in the American League West. After the 1984 season began with a similarly lackluster 20-24 record, Oakland ownership fired Boros. Jim Leeke, in a biography of Boros for the Society for American Baseball Research, wrote, “Oakland’s players were never quite comfortable with their manager.” Some of them were apparently also resentful of the role played by the computers. Dwayne Murphy, whom Boros mentioned during his Chronicles appearance, reportedly “grumbled” to Boros after being thrown out during a rundown between second and third base that “[t]he computer made me do it.”

Boros later joined the San Diego Padres as coordinator of instruction for the team’s minor league staff. In 1986, he took over as manager when the incumbent, Dick Williams, failed to show up for the first day of spring training. (Williams told the press he simply didn’t want to manage the Padres for another year.) According to Leeke, Boros’ 1986 in San Diego was “eerily familiar” to his 1983 in Oakland. Indeed, the Padres finished the year with the same 74-88 record.

After that, Boros returned to his previous role overseeing the Padres’ minor league instruction staff. Boros never managed again but continued to work in baseball up until 2004. He spent the final nine years of his career back with the team he started with as a player, the Detroit Tigers, retiring as a special assistant to the general manager.

Boros passed away from complications due to cancer in 2010 at the age of 74.

Anderson a Hall of Famer in Tennis and Teaching

The other coach who appeared in this episode, Rich Anderson, ran the men’s tennis program at Cañada College, a community college located in San Mateo County, not far from where Computer Chronicles taped. During Anderson’s tenure, which lasted from 1971 to 1983, his teams posted a combined record of 142-15, including 11 conference titles and eight California state junior college championships. Anderson himself was an accomplished player in his own college days at San Jose State University, where he reached a No. 17 national ranking and participated in both the U.S. Open and Wimbledon.

In 1983, Anderson accepted an offer from Cañada College to step back from coaching and teach computer science. Anderson went on to spend more than 30 years in the classroom, retiring in 2006. Upon his 2014 induction into the USTA Northern California Tennis Hall of Fame, it was noted that Anderson achieved “the unique distinction of being both an athletic Hall of Famer and earning a Teaching Excellence Award from the California Community Colleges Math Council.”

Sports Alone Could Not Save Qantel

As both Billy Hicks and Paul Schindler alluded to, the 1985 Super Bowl between the Miami Dolphins and San Francisco 49ers was also a matchup of two MDS-Qantel customers. Indeed, according to a January 1985 InfoWorld article, the teams from the three previous Super Bowls were also Sportspak users.

The company behind Sportspak itself had a rather tumultuous history. Qantel Corporation started in 1969 in Hayward, California. The company’s early focus was on producing minicomputers for businesses. In 1981, New Jersey-based Mohawk Data Sciences (MDS) acquired Qantel and kept it running as a standalone division.

During the 1980s, Qantel was apparently Mohawk’s best-performing unit. The New York Times reported in October 1984 that analysts believed that half of Mohawk’s reported $400 million in 1983 revenues could be attributed to Qantel’s sales of minicomputers and software. The Times noted there were roughly 10,000 Qantel minicomputer systems installed and that “sports applications” were an important factor in Qantel’s 20 percent annual growth rate.

In contrast to Qantel, Mohawk as a whole reported a $53 million loss for the 1983 fiscal year, forcing the ouster of the company’s chief executive. The October 1984 Times report said Mohawk was a tempting takeover candidate based on Qantel’s strength alone. Actually, the reverse happened when just a year later, Mohawk sold five of its under-performing units to a private buyer, keeping only its “strongest asset” in Qantel. Mohawk later renamed itself Qantel and sputtered along for a few more years until it filed for bankruptcy in September 1991. Most of Qantel’s assets were sold in bankruptcy to Decision Data Computer Corp. and Sussex Investments Ltd. In 1996, a new company called Qantel Technologies acquired some of those assets. That company apparently still exists today.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has an original broadcast date of March 5, 1985.

- Lawrence L. Cone wrote a detailed article for the October 1985 issue of Byte discussing his role in developing the control software for SkyCam, the subject of one of Wendy Woods’ features. Cone said he used an Osborne 1 to develop the program over a period of eight months. SkyCam itself debuted during a preseason game between the San Diego Chargers and the San Francisco 49ers.

- CompuTennis was founded by Bill Jacobson, described in a September 1984 Sports Illustrated profile as a “former South African amateur who had been applying computer technology to projects involving geophysical exploration.” The CT120 was quickly adopted by the tennis community and remained the “industry standard” for statistical analysis until the mid-1990s.

- The other Wendy Woods’ subject, North Sails, is still very much in business. The privately held company started in 1957. It introduced the concept of “digital sail design” in 1977. The in-house computer designed process described in Woods’ report apparently utilized a Cromemco microcomputer.

- Richard Bunch remained with Converse until 1989. His most recent position was with PerkinElmer, where he served as director of its microfluidics technology division from 2012 to 2016.

- The IBM Watson described in “Random Access” should not be confused with the present-day IBM Watson artificial intelligence system. Both were presumably named for former IBM chief executive Thomas J. Watson, Sr.

- Billy Martin, the manager that Steve Boros replaced in Oakland, was definitely not a fan of computers. He told Ray Kennedy, “I don’t need that stuff. I’ve got it all up here,” referring to his head.