Computer Chronicles Revisited 27 — Sargon III, Millionaire, and Ghostbusters

The original Macintosh would not seem like an obvious gaming machine. It retailed for $2,500 at the time of its January 1984 release. You could have bought a dozen Atari 2600 consoles for the same amount of money. And while the Macintosh did boast high-resolution bitmap graphics–as well as the ability to display multiple windows–it came on a 9-inch monochrome display. Even the lowly Commodore 64 could display 16 colors, and use an ordinary television set to boot.

Still, Apple was determined to avoid a repeat of the Lisa’s failure by ensuring the availability of third-party software for the Macintosh platform. Games were an obvious candidate. To that end, this next Computer Chronicles episode featured two of the earliest entertainment offerings for the original Macintosh–as well as a look at one of the most iconic games for the more popular Commodore 64.

Would Computer Games Stumble Like Video Game Consoles?

Stewart Cheifet’s cold open featured him standing in an electronics store holding up a retail version of the legendary Atari 2600 game E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial video game. Cheifet said that video games had come on hard times these days with closeout sales and discount prices just about everywhere. But what about computer games? As computers have gotten better, Cheifet said, so have the games, which boasted vastly improved graphics, much more sophisticated text handling, and greater speed.

In the studio introduction, Cheifet and Gary Kildall demonstrated the Milton Bradley Grandmaster (also known as the Milton Bradley Phantom), a chess-playing computer that could actually move the pieces on its own using magnets and a robotic arm concealed underneath the board. Cheifet noted that computer games drove much of the early personal computer revolution, but some people were now saying that computer games were actually dying. Kildall quipped that from the looks of the automated Grandmaster chessboard, it may be the game player was a dying breed. But seriously, Kildall said he did not think the market for computer games was dying. Rather, the market had settled down to a group of dedicated game players and those players now expected fairly sophisticated games.

Adapting Film Animation to Computer Game Design

Wendy Woods then presented her first remote piece of the episode, which explained how traditional animators were now moving into computer game design. Over some B-roll of a game under development–it appeared to be the 1985 Broderbund release Captain Goodnight and the Islands of Fear–Woods noted that the early art of animation had grown up alongside the motion picture industry. It was based on storyboards, character development, and a detailed script. This was a repetitive and time-consuming process. But today, many of these tasks could be computer assisted, which had great potential for the field of computer games.

Woods explained that a game designer could dream up a character, give them a personality and lifelike moves, and quickly bring their paper sketches to life on the screen. Using a light pen, the artist could adjust each pixel on the screen to give their character fluid movements. All of the critical game elements, from game action to the backgrounds, could be drawn on a graphics pad, tested, and changed instantly.

To create an explosion, for example, Woods said the animator first determined the shape and size of the blast before building a sequence. After checking the result, the animator could then place the explosion precisely within the scene. But in spite of electronic aids, the present-day designer was still faced with a monumental challenge–to transfer the personality of an invented character from the full-size drawing pad to the tiny pixels on a video screen. This required finesse and detail.

For instance, when the hero of the game was introduced, the animator wanted his movements to be quick and bold. But when faced with adversity, the hero’s mood reflected it and he would slink away with slumped shoulders. To most players, Woods said, this might not seem like a major step forward, but it resembled the methods used to make traditional animation lifelike. The more plastic and fluid the movement, the more realistic the action. How much of this realism could be transferred to the electronic game board remained to be seen.

Using Your Mac to Play Chess…and Simulate Stock Transactions

Back on set, Kathe Spracklen and Jim Zuber joined Cheifet and Kildall. Spracklen was the co-writer and designer (along with her husband, Dan Spracklen) of Sargon III, a chess program available on the Macintosh. Kildall noted that one of the amazing things about computer chess games was that 15 or 20 years ago it was essentially a research topic and today you could walk into Macy’s and buy a tiny chess computer. Kildall asked what allowed that to take place. Spracklen replied it was obviously the microcomputer revolution, i.e., the existence of a single-chip computer. It was like if a new mountain sprung up and all of the mountain climbers would rush to it–the same was true, she said, for programmers when a new microprocessor came out.

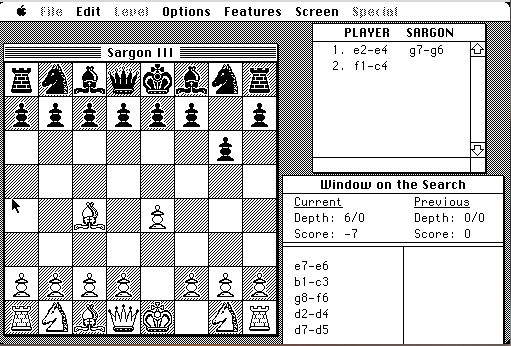

Kildall asked Spracklen about the process of constructing a computer chess program. Spracklen replied that as with any big project, you had to break it down into manageable steps. For Sargon, Spracklen said that meant dividing the program up into three separate components: (1) move generation–how did you get the machine to understand what is pawn move, a queen move, et al.; (2) evaluation–now that you can make moves, which are good or bad, and how fast can the computer calculate its options; and (3) graphics displays and user interface.

Kildall noted that the Macintosh offered a very graphical interface. Was that a big change versus developing Sargon for earlier machines? Spracklen said it was a big change and a “delightful” one at that. She said working with the Macintosh was like presenting a kid with a mountainous ice cream sundae–it was everything you ever wanted in a computer but never had before.

Cheifet asked Spracklen how she directly used the Macintosh to augment Sargon? Spracklen said that in prior versions, the player had to type in their moves using traditional chess notation. Now, the Macintosh allowed the player to simply use the mouse to move the pieces. Indeed, aside from naming a save file for a game, the player never had to touch the keyboard.

Kildall asked how Sargon III fared against good chess players. Spracklen said it beat the majority of tournament-level chess players and the vast majority of casual players. However, a world champion chess player would have no difficulty beating the program–Sargon III might beat such a player once in 100 games, she said. Kildall asked if Spracklen herself could beat the game. She said she could on the lowest level.

Cheifet asked how Sargon III made improvements over its predecessors, Sargon and Sargon II. Spracklen said each version involved a complete rewrite of the chess-playing algorithm. Each version also represented a tenfold or better improvement in speed. In practical terms, it took the computer 2 or 3 minutes to make a move in Sargon II, but in Sargon III it was more like 5 or 10 seconds.

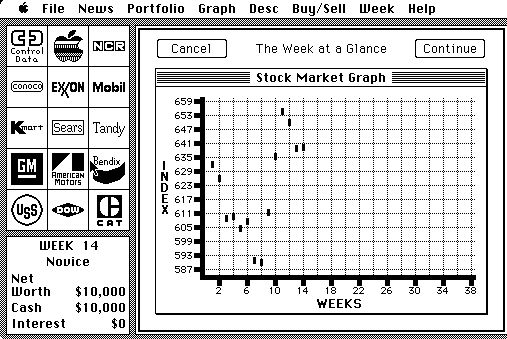

Cheifet then turned to Zuber, who designed a game called Millionaire for Blue Chip Software. Zuber explained his game was a stock market simulation. He said that after doing some consulting work a few years earlier, he’d taken his money and invested in stock options. He learned an awful lot about how the market worked–although he lost half of his money. Around that same time, the IBM Personal Computer was coming onto the market. Figuring that the type of person who would buy a PC was likely an upwardly mobile individual concerned with their net worth, Zuber decided to write his simulation. Later, about 6 months before the release of the Macintosh, Zuber said Apple came to him and asked about a version for its new machine. A couple days after that, a programmer who had spent the past year programming the Macintosh for the accounting firm Peat Marwick offered his services in porting the software.

Zuber then gave a brief demonstration of Millionaire, which made heavy use of the Macintosh operating system’s menus and windows. The basic premise of the game was fairly simple: The player could invest in 15 different stocks (all real-world companies) representing 5 different industry groups and track their portfolio over time. Kildall asked if this would actually make someone a better investor. Zuber said it would not, although it could help teach you how to avoid certain mistakes.

LucasFilm Enters the Computer Game Market

Before the final in-studio segment, Wendy Woods returned with her second remote feature, this time focusing on the first computer game releases from George Lucas’ LucasFilm. The first game, Rescue on Fractalus!, was a first-person aerial combat shooter where “space, form, mass and velocity are seen to true to life.” LucasFilm designer David Levine told Woods the game was based on a geometrical formula known as the fractal, which measured the altitude at various points and then used a repeatable technique for generating the craggy or rocky edges to create the game’s mountainous playing field.

The second game, Ballblazer, was designed by Levine to be a kind of space-age hockey that featured a split screen showing both players’ point of view. Woods said the edges of the diagonal playing field appeared to be smooth thanks to a technique known as anti-aliasing, which blended five different colors at certain grid points. Woods noted it took LucasFilm designers about a year to complete both of these games. David Fox, the designer of Fractalus, said that at LucasFilm they did not have a marketing organization “beating down their necks” telling us to get a game done in 3 weeks. They were simply told to do the best they could do and push the technology as far as they could. Woods ended by noting that LucasFilm’s next games would target the newest low-end personal computers.

From Text-Based Adventure Games to Movie Tie-ins

Back on the set, David Crane and David Lebling joined Cheifet and Kildall. Lebling authored a number of text-based adventure games, notably the Zork series, for Infocom. Kildall asked Lebling to explain what made an adventure game interesting, particularly in a world that was now moving towards graphics. Lebling said the human brain could do a much better job of creating the pictures than a computer could with today’s technology. That was why all of Infocom’s games were text.

Kildall followed up, asking if the games were getting more sophisticated now. Lebling said they were, to the point where they weren’t even mostly played by children anymore. He noted the appeal of adventure games did not fade with age, and a lot of adults still enjoyed them. He also explained that unlike the earlier adventure games, which relied on simple “branching” techniques, today’s programs could recognize much more complex directions and verbs. The player could talk to other characters inside the game and even ask fairly complicated questions such as, “Where were you on the night of the murder?”

Cheifet mentioned he was a fan of the old Scott Adams adventure games that involved very simple commands like “GO NORTH” or “DROP BOX.” He noted that Infocom had come a long way with games such as Zork. Cheifet asked what made today’s games so much better. Lebling said that Infocom had an extremely good development system and parser built into its games. The parser could now understand more complex sentences. And the more sentences the game could understand, the more complicated and exciting the action in the game itself.

Cheifet then turned to David Crane, a game designer and co-founder at Activision. Cheifet noted Crane was known for graphics-based video games like Pitfall. Did Crane think that computer games would suffer the same fate as video games, or were computer games a different animal where consumer interest wouldn’t die? Crane replied there were going to be several different classifications of games going forward, such as adventure games, strategy games, and arcade games. One of the most difficult aspects of the industry right now, he said, was categorizing games due to crossover. For example, his newest game Ghostbusters was an action game. But unlike earlier action games that took place on a single screen, there were several different screens involved in Ghostbusters

Crane then demonstrated Ghostbusters on a Commodore SX-64 (a portable version of the Commodore 64 with a built-in display and disk drive.) The game opens with a title screen playing the theme song from the 1984 movie upon which the game is based. Cheifet joked it must have taken Crane as long to do this title screen as the rest of the game. Crane said that wasn’t really true; he actually waited until the final week of development.

Cheifet pointed out that up until now, computer games were noted for their innovation. Did it concern Crane at all that Ghostbusters was simply repackaging a movie? Crane said he was not concerned by that. In fact, he began work on this game before the movie ever came out. What his initial game lacked, however, was a theme. So when Activision and Columbia–the studio that released Ghostbusters–decided to get together, Crane said he saw it as an opportunity to lend a theme to his game. But he added that many people had told him they would enjoy playing Ghostbusters even if it didn’t tie-in to the film.

Crane then continued to demonstrate some of the features in Ghostbusters. The game starts by asking if the player has an “account number.” This was an early type of password system where a player could start the game with the same amount of cash that they did following their last session. If the player did not have an account, they started out with funds loaned from the bank. The player then had to purchase a car and ghost-hunting equipment. The main game play involved driving around a city to various locations where the player would then try to capture ghosts.

Finally, Cheifet asked Lebling about what he saw as the next challenge in adventure games. Lebling said he expected games would start moving away from straight puzzle solving and into something more akin to the plot of a novel.

No Substitute for Human Interaction

Paul Schindler’s closing commentary for the episode attempted to throw a bit of cold water on the growing popularity of computer games. He presented his commentary lying on the floor of his house while his daughter played the board game Candy Land. Schindler noted the board game was good for improving his daughter’s color identification and verbal skills–as well as teaching her not to cheat. Could a computer game do that?

Schindler said he knew computer games had a good side–indeed, he reviews computer games–but we had to consider the social effect of replacing other kinds of games with the computer. For instance, he said he offered covered industry conventions in Las Vegas, where he also liked to play blackjack. Would you rather play that game with people or the computer? Schindler said he preferred the interaction and learning you got from playing with people. And it would be a long time before the computer could offer that same degree of human interaction.

GM Announces Its First Computer in a Car

Stewart Cheifet presented the Random Access segment following this episode:

- Grid Systems, known as the “Porsche of lap portables,” announced a new line of computers starting at about half the price of the company’s existing Grid Compass. The new lineup would let customers pick the type of screen they wanted based on “readability vs. power consumption.” Grid would offer both LCD and Plasma displays. Cheifet said Ericsson, Kaypro, and Morrow Designs all planned to release new portable PCs as well during 1985.

- New software called the Spinal Health Data Program now allowed doctors to digitize X-rays into high-resolution graphics using an IBM Personal Computer.

- A company called Defracto–I may have the name wrong–planned to release a new line of “robots with eyes.” Specifically, the robots used solid-state video cameras, strobe lighting, and computerized wraparound lasers to sort through up to 10,000 objects per hour and spot any imperfections.

- In more new computer news, Tandem Computers said it would unveil a line of “low-cost failsafe minis” to run in offices.

- Paul Schindler returned for his weekly software review. This time he reviewed what a freeware program called Free Will, which was published by the San Francisco PC Users Group to help people write their own wills. Schindler noted the freeware model was the “opposite of copy protection,” in that users were encouraged to copy and distribute the program without permission. Satisfied users were encouraged to pay a $6 registration fee.

- General Motors said the 1986 Buick Riviera would come with a full onboard computer–including a touch-sensitive CRT display on the dashboard–that would oversee about 100 different functions inside the vehicle.

- A company called Amfit announced a new process that used computers to help build custom shoes for customers.

- Finally, Cheifet noted there was growing interest in replacing the traditional QWERTY keyboard with the Dvorak layout, which proponents claimed resulted in 50 percent faster typing speeds. Nevertheless, with 30 million QWERTY boards already in use, Cheifet said prospects for a quick change were dim.

Spracklen’s Journey from Early Computer Chess to Sewing and Crafts

As I mentioned in my introduction, Apple was keen on having third-party software available for the Macintosh. Kathe Spracklen discussed the process of bringing Sargon III–which was originally written for 6502-based machines–to the Motorola 68000-based Macintosh in a 2005 interview conducted by Gardner Hendrie for the Computer History Museum:

When the Apple Macintosh computer came out, Apple pre-released some development systems with people who had successful products, in the hopes they would get their programs running, on the new Macintosh computer. Now, we weren’t in the first round. But just a couple weeks before they announced the Macintosh, or maybe a couple of months, one of the developers dropped out. And so Apple contacted us and said would we like to put our Sargon on a pre-release Macintosh? So we took it on, and we did it. And we translated the entire program into 68000 [assembly language].

Spracklen said Sargon III ended up becoming the “first third-party executable software program for the Macintosh.” Interestingly, Specklen said Apple co-founder Steve Jobs wasn’t interested in Sargon when they initially met at the second West Coast Computer Faire in 1978. That event marked an important point in the development of Sargon, as the game–originally designed by Spracklen’s husband, Daniel–managed to win a contest held among various computer chess programs.

The Spracklens originally developed their chess program for a Z80-based computer called the WaveMate Jupiter II, which cost them nearly $4,000, representing their total savings at the time. Dan Spracklen built the original chess algorithm, while Kathe Spracklen programmed the machine’s graphics.

After Sargon won the West Coast Computer Faire tournament, Kathe Spracklen said someone from the journal Byte approached her about writing a series of articles for the magazine about the program. The published articles included a plug for people to buy Sargon–not an actual disk or cassette tape, mind you, but a printed listing of the source code. Daniel Spracklen said he and Kathe “were putting [Sargon] into a bound copy and Xeroxing it, and just selling that for $15.00.”

Eventually, Hayden Books agreed to publish the Sargon code as an actual book. Kathe Spracklen noted when she went to look at the “computer section” of her local Barnes & Noble, the only two books available were hers and a guide to building your own robot. Hayden Books later established a software arm that actually published the later Sargon games as commercial software.

During this time–and in fact, up until the early 1990s–both Spracklens worked full-time for Fidelity Electronics, a company that initially made its mark selling hearing aids and biomedical products but later pivoted to making dedicated chess computers, most of which were designed by Dan and Kathe Spracklen. The machines proved successful, winning the first four World Microcomputer World Chess Championships.

After leaving the world of computer chess, Kathe Spracklen went to work for a researcher studying the causes of juvenile delinquency. After helping to publish a number of papers on that subject, Spracklen briefly taught programming at a community college in Oregon. She then went to work developing software for a distributor of sewing crafts and supplies, which she described to Hendrie as “the love of my life.”

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has a broadcast date of January 21, 1985.

- Starting with this second season WITF-TV, the public broadcasting station in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, now co-produces Computer Chronicles with KCSM-TV in San Mateo, California. This coincided with Cheifet taking over as WITF’s president and chief executive, a post he would hold until 1993. Going forward, we will see some WITF personnel presenting “Random Access” and some remote segments.

- The MB Grandmaster seen during the introduction is actually based on a variant of the 6502 microprocessor that was used in many early personal computers, including the Commodore 64 and Apple II.

- All roads apparently lead to Activision: David Lebling’s Infocom merged into David Crane’s Activision in 1986. Activision kept Infocom going as a separate division until 1989. Meanwhile, Hayden Software, which published Kathe Specklen’s Sargon III, was sold off to Spinnaker Software, who in turn later sold it to–you guessed it–Activision.

- Not long after this episode aired, Jim Zuber left Blue Chip Software and co-founded Genoa Technology, a software testing company, which later became known as QualityLogic. Zuber remains affiliated with that company to the present day.

- As for Blue Chip Software, it produced three other business simulation games in the early 1980s–focusing on financial planning, commodities, and real estate, respectively–but seems to have disappeared into the ether after doing a second release of Millionaire in 1987.

- Some of the 15 companies used in Millionaire are now defunct, including Control Data Corporation, which I discussed back in Part 25.

- Dave Lebling apparently left the computer games industry after the demise of Infocom. He recently retired after a long stint as a senior principal software engineer for BAE Systems, a United Kingdom-based defense contractor.

- Of today’s four guests, only David Crane stuck with computer game design. He did leave Activision in 1986 to co-found Absolute Entertainment, where he developed David Crane’s Amazing Tennis and Bart Simpson’s Escape from Camp Deadly, among other games. Most recently, Crane and longtime collaborator Garry Kitchen released Circus Convoy, a brand new game for the Atari 2600, through their Audacity Games label.

- Crane also provided a more detailed explanation of the “account number” password system for Ghostbusters as part of an August 2020 video posted by Christian Simpson on his Retro Recipes YouTube channel.

- I wonder if the comment from LucasFilm’s David Fox about not being pressured into making a game in three weeks was a veiled shot at Atari’s infamous release of E.T., which was famously designed in just five weeks.

- Paul Schindler’s disdain for computerized blackjack seems to be at odds with his earlier positive review of Ken Uston’s Professional Blackjack.

- Tandem Computers was primarily known for making “fault-tolerant computer systems,” i.e., computers used in ATMs and switching centers. The personal computer line mentioned by Cheifet would be known as the Dynamite PC. It apparently fizzled on launch.

- On the other hand, Amfit would find success in the area of computer-aided custom shoe design. The company remains in business to this day.

- GM did release the 1986 Buick Riviera with a computer. Known as the Graphic Control Center, the 3x5 CRT display allowed the driver to adjust the car’s climate control and radio, as well as access a variety of diagnostic systems, according to a 1986 article in the Christian Science Monitor.

- Still waiting for the Dvorak keyboard to make its move. Any day now…