Computer Chronicles Revisited 21 — The Apple Graphics Tablet, SGI IRIS 1400, and Quantel Paintbox

Personal computers of the early 1980s were often limited to just a few colors for on-screen graphics. The Apple IIe, for example, could display up to 16 colors at one time depending on the screen resolution. And of course, no home computer of this era could produce genuine 3D graphics. That capability was limited to very high-end machines designed for industrial or commercial use.

The Special Talents of Computer Graphics

Which brings us to our next Computer Chronicles episode from 1984. The subject is computer graphics. And while Stewart Cheifet does open the program with a demonstration of a graphics peripheral designed for personal computers, most of the program is devoted to technology that was beyond the financial or technical capacity of the home user.

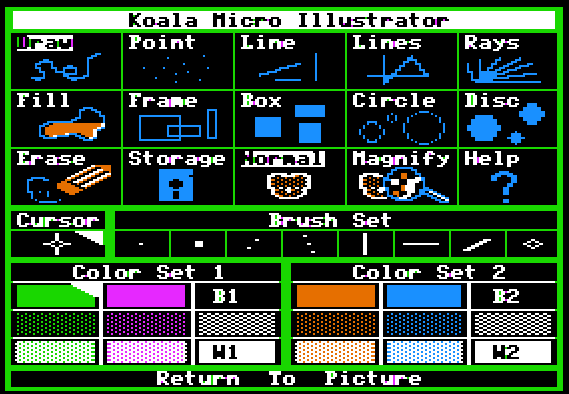

Cheifet, joined by returning guest host Herbert Lechner, showed off the KoalaPad, a graphics tablet designed for most popular microcomputers of the day. In this case, it was hooked up to an Apple IIe. Cheifet demonstrated how you could simply draw on the screen using the tablet. He said that computer graphics were often associated with drawing or video games, but they were also used in more serious applications. Lechner concurred, noting that computer “fine art” was now hanging in galleries right alongside traditional art. And in the commercial area, Lechner said computer graphics systems aided animators and played an important role in producing television advertising.

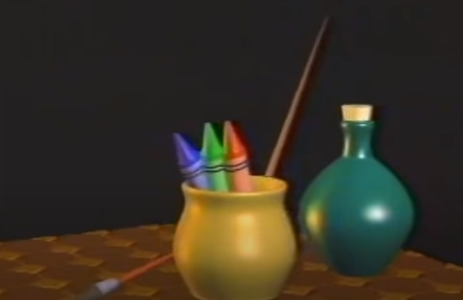

The B-roll for this episode included footage of Ron MacNeill, a computer artist with MIT’s Visible Language Workshop. Cheifet explained how MacNeill used a digitizing tablet to choose from a palette of colors and pre-programmed images to create a collage that existed only in the memory of a computer. MacNeill started with materials from different sources, such as photographs and 3D objects, to make a composite that could then be manipulated to change their colors, sizes, and geometric aspects. The final hardcopy was then printed using a plotter to create a wall-size mural that was 14 feet high and 48 feet long.

Cheifet said the “special talents” of computer graphics were also increasingly used in another area of the visual arts: animation. Once again, an artist could use a digitizing tablet to create a figure by drawing in just enough points to determine its size and rough shape. For a symmetrical object, Cheifet said all the computer needed was an outline of one side, which was then shaped into a fluid form, regenerated, and filled with color and other 3D details. The software could then calculate and reproduce the characteristics of light and shadow that the object would possess in three dimensions. Finally, to animate the drawing, the artist could specify key camera positions from which the object was viewed in space. The program then filled in the missing frames to simulate movement between those points. Cheifet said that making a drawing come to life was “the most tedious part” of an animator’s job–but fortunately, it was also readily adaptable to digital processing.

Over some computer graphics demos produced by Pacific Data Images (see one below), Cheifet emphasized that the systems used to produce these images were not designed to replace artists but to assist them. And with enough human talent, he said, artists could use computers to mimic reality in greater detail or expand it to the fringes of their imagination.

It Takes a Lot of Computing Power to Move a Rubik’s Cube

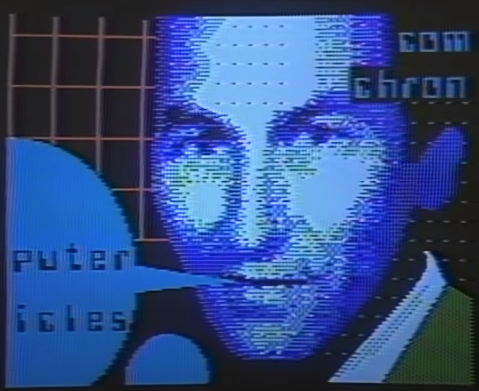

Michael Arent and Donald McKinney joined Cheifet and Lechner for the first roundtable segment. Lechner asked Arent, a digital artist and consultant with Aaron Marcus + Associates, for a demonstration of the work he did using an Apple Graphics Tablet. Arent showed you could use the tablet to not only paint images, but also combine graphics, photographs, and text onto the screen. Specifically, he took a digitized photo of Cheifet, removed the background, and added a word balloon with text.

Cheifet pointed out that computer graphics demanded a great deal of memory. How was that accomplished on a microcomputer like the Apple IIe? McKinney, a vice president with Silicon Graphics, Inc. (SGI), replied that it depended on the amount of color that you had available as well as the screen resolution. The higher and smoother that the image appeared, the more memory memory you required, McKinney noted that SGI’s own system, which he would demonstrate in a moment, required approximately 3 million bytes of memory to store an image in real time.

Returning to Arent’s demo, Lechner asked how it was possible to remove the background of an image. Did it involve tracing around the image? Arent said yes, the Apple Graphics Tablet had a function that allowed him to “block out” the background by painting it black. Cheifet asked for more specifics on how the tablet worked. Arent said it directly addressed various areas within the Apple IIe’s memory, essentially commanding it to put color or geometric figures onto the screen.

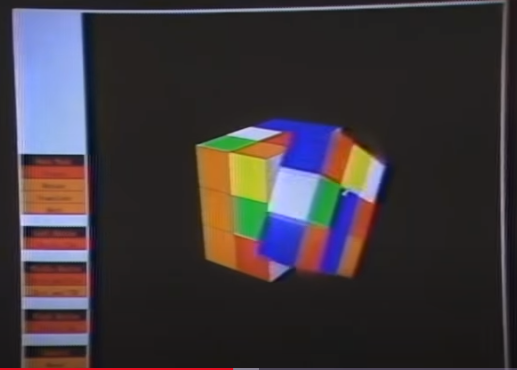

Cheifet and McKinney then moved over to the other side of the studio to demonstrate SGI’s IRIS 1400 computer graphics system. Cheifet asked how this differed from the Apple Graphics Tablet or the KoalaPad. McKinney explained that those devices worked with microcomputers. But the IRIS was a different class of machine. The main difference was that it used custom chips developed by SGI to perform 3D calculations. He then provided the first demo, which was a Rubik’s cube moving in 3D space.

Cheifet asked about the hardware used in the IRIS 1400. McKinney said the CPU was a Motorola 68000, which was also used in many high-performance microcomputers (such as the Apple Macintosh). He said the other key was the Geometry Engine, a propriety SGI high-speed 3D floating-point calculation unit that could perform 6.5 million operations per second. In the near future, McKinney said SGI planned to increase that speed to 10 million floating-point operations per second.

McKinney’s next demo was a virtual fly-by of some 3D-rendered buildings. Cheifet asked about the practical application of this technology. McKinney said SGI had several customers in the architectural, engineering, and construction fields. Indeed, many local companies in the Silicon Valley region used the IRIS system to create piping diagrams and perform calculations for intersections in facilities like nuclear power plants. It was also possible for an architectural firm to add their own software to the IRIS system and sell it to end-user architects for use in designing exteriors and landscapes, or even interior decorating.

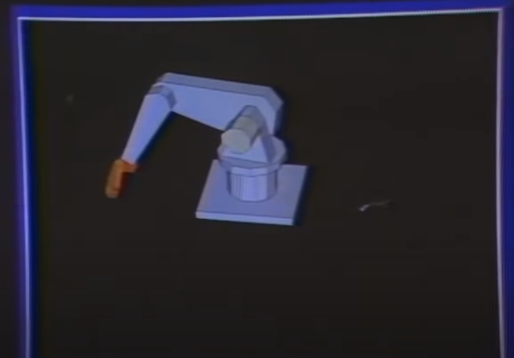

There were two additional demos, one showing a 3D robotic arm and the other a flight simulator.

The Wave of the Future for Television Graphics

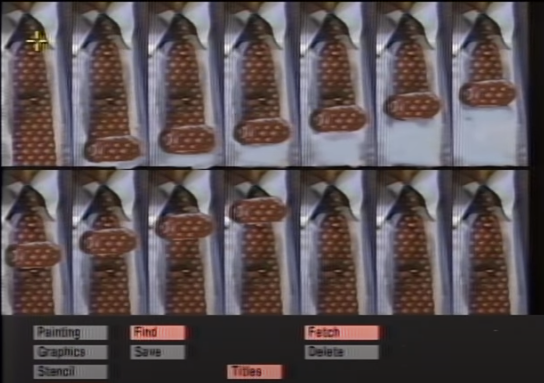

For the second and final roundtable, Ann Chase and Kevin Prince joined Cheifet and Lechner. Chase, a freelance digital artist, demonstrated the Quantel Paintbox. She used the Paintbox to create a digital animation of Stewart Cheifet’s necktie rolling up and down during the transition to this segment.

Cheifet asked Prince, an engineering manager with Quantel, about the hardware and software capabilities of the Paintbox. Prince said like the SGI IRIS system, the Paintbox also used a Motorola 68000 CPU. Quantel also included a lot of dedicated hardware to provide capabilities like fast wipes, painting, changing brush sizes, and so forth. He added this system required a very large operating system that took Quantel quite a bit of time to develop.

Chase then briefly showed how you could draw freehand using the Paintbox. Chiefet observed that this was much finer drawing at a greater resolution than what the products demonstrated earlier could achieve. Prince explained the Paintbox relied on various methods of mapping and storing images that differed from “individual pixel” operations that those other machines used.

Cheifet noted that the Paintbox was currently used to produce television graphics. Prince said most of the television networks actually had “several” systems, which were primarily used for daily news production. He added the graphics technology was so good that most viewers didn’t even notice.

Chase then performed a final demonstration, showing how you could “cut and paste” images with the Paintbox. Taking a still image from the live video feed of the Computer Chronicles taping, Chase pasted a duplicate image of her own head on top of Prince’s body.

Lechner said that while it was clear this type of computer graphics technology was valuable to the television industry, what about fine art? Was “computer art” growing and catching on? Chase said definitely–computer art was the “wave of the future.” Lechner jokingly asked if paintbrush manufacturers should be worried.

Finally, Cheifet asked how far could we go with this technology? Would we get to the point where we–meaning people like himself and Lechner–could be replaced by animated people who were synced up with spoken words? Prince said he sincerely hoped not. At the moment, Quantel provided the means for an artist to extend their capabilities. The idea was to turn a reasonable artist into a good one, and an extremely good artist into a superb one. All the technology did was allow the artist to complete their work in a much shorter space of time.

McKinney Makes IT Big in Network Services

Of today’s four guests, the one who has likely seen the most financial success is Donald McKinney. McKinney remained with Silicon Graphics as its vice president of sales until 1987. In 1992, he founded International Network Services (INS). Ostensibly a consulting company, INS became known as the temporary staffing agency for network engineers in Silicon Valley during the 1990s, according to a 1998 profile in the New York Times:

I.N.S., founded in 1991, does not manufacture equipment. It does not run computers. It does not re-engineer business processes. It does not develop corporate strategies. What I.N.S. does do is design, manage and secure communications networks. And the company does it so well that it has become the network engineers’ engineer – the expert that the network experts can turn to when they need a specialist’s touch.

Besides Bell Atlantic, the other telecommunications and technology giants that have used I.N.S. include AT&T; MCI Communications and the partner in its recent merger, Worldcom; SBC Communications; Sprint; BellSouth; Cable and Wireless; Airtouch; GTE; Cisco Systems; Compaq Computer and Oracle.

McKinney had stepped away from day-to-day oversight of the company when this article was written. And about a year later, Lucent Technologies acquired INS in a $3.7 billion all-stock transaction, which made McKinney a billionaire, as he still owned about one-third of the company. Since the 1999 sale, McKinney has been a “private technology investor” in companies like Keyssa.

Prince Makes Chyrons

Kevin Prince left Quantel in 1984, presumably not long after his Computer Chronicles appearance. He’s continued to work in the television media end of the computer graphics industry. In 2004 he became chief operating officer of Chyron Corporation, whose early computer graphic systems from the 1970s gave rise to the term “chyron” as a generic reference to the “lower third” overlay during news and sports broadcasts.

Chyron merged with a Swedish company, Hego AB, in 2013. Prince remained with the newly renamed ChyronHego as a senior vice president. He left the company in 2015 to become president and CEO of Broadcast Pix Inc., a Boston-based company that “creates integrated production switchers, as well as cloud-based solutions for media management, collaboration, and distribution.” According to Bloomberg, Prince served as CEO until August 2019.

Arent Makes Mark in UI Design

Michael Arent’s career took him from producing freelance digital art to designing user interfaces for major tech companies. He joined Apple in 1988 to work on the UI for what became Macintosh System 7. He was also part of the original team behind Apple’s QuickTime multimedia framework. After departing Cupertino in 1994, Arent worked as a senior interaction designer for Tele-TV, a short-lived joint venture between several of the “Baby Bells” and the Creative Artists Agency to produce interactive television systems.

Following stints at Sun Microsystems and Peoplesoft, Arent joined SAP Labs in 2005 as vice president of user interface standards. He remained with SAP until 2013, when he moved to GE Software as its director of user interface design. Arent left that position in 2015 and appears to be semi-retired. He’s currently an officer and director with the nonprofit Counter Culture Labs, which is described as a “community supported microbiology maker space.”

IRIS Offered Performance for a Hefty Price

We’ll no doubt see more from Silicon Graphics in future Computer Chronicles episodes, as the company was a powerhouse in the 3D market during the 1990s. For now, this December 2020 retrospective on the company by Cal Jeffrey provided some additional background on the IRIS systems demonstrated in this episode:

SGI released its first-generation IRIS systems (models 1000 and 1200) in 1984. These were not standalone workstations, but rather raster display units intended to be connected to more general-purpose machines like the DEC VAX. The early IRIS models used a PM1 CPU board, a variant of the one used by Stanford’s SUN workstation that David Brown had helped develop. These systems came equipped with 8 MHz Motorola 68000 processors and 768kB of RAM but no disk drive.

Later that same year, SGI would launch the 1400 and 1500. Each machine got a bump up to 10 MHz and 1.5 MB RAM. They also each had disk drives. The 1400 had a 72MB ST-506, and the 1500 sported a gigantic 474 MB SMD-based drive with a Xylogics disk controller.

McKinney never directly identified the machine he used in this episode as the 1400, but given that it had a disk drive–Cheifet kept swapping the disks out for each demo–I’m assuming that was the machine.

Jeffrey noted that while SGI only sold about 3,500 machines total in the IRIS line, each unit cost between $45,000 and $100,000. Indeed, according to an archived 1984 email from a Silicon Graphics product manager, the IRIS 1400 sold for $22,500–but that took into account a 40 percent educational discount. This meant the “retail” price of the 1400 was $37,500.

Paintbox Dominated the 80s Mass Media Market

Of course, the IRIS 1400 was still a bargain compared to the Quantel Paintbox. A July 1984 article in the New York Times described how the three main television networks used the Quantel system to beef up their sports and upcoming presidential election coverage. With respect to NBC, the Times noted:

The network has increased its artistic staff by 30 percent, to more than 50, and invested in no fewer than nine Paintboxes. These devices, which allow an artist to draw directly onto a screen with an electronic stylus, cost about $150,000 apiece. (Emphasis added)

The Times also cited an ABC executive, who said that while the company once required a “staff of artists” to draw on-screen graphics, “with the Paintbox an artist can come up with a graphic in 15 minutes that used to take two days.”

The United Kingdom-based Quantel made its reputation with the Paintbox. Roland Denning, writing for RedShark noted the machine was used in the production of the famous Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” music video in 1986. But while the Paintbox “was still growing strong in 1990,” according to Denning, it was displaced by the middle of the decade by the rise of Adobe’s Photoshop software and never recovered:

Sadly, Quantel was to go the way of all high-end systems based on proprietary hardware and the company began to contract from 2005 onwards. In 2014 it acquired Snell, formerly, Snell & Wilcox, another British high-end hardware-based manufacturer, famous for their Alchemist standards convertor. In 2015 the Quantel name was dropped and what was left of the company became subsumed by SAM (Snell Advanced Media), to be acquired by Belden in 2018 and then incorporated into Grass Valley. The Rio, stripped of its Quantel name, lives on under the Grass Valley brand and claims to be ‘the world’s only real-time 8K 60p colour and finishing system’.

Apple Graphics Tablet Faced Early Setbacks

In an unusual reversal, Apple offered the cheapest product demonstrated in this episode. That’s really no surprise, given that the Apple Graphics Tablet was a peripheral designed to work with an Apple II. Based on a retail magazine advertisement that I found, the tablet sold for about $120 as of late 1982. Although this was presumably the original version of the tablet, which Apple released in 1979 at a retail price of $650. According to the Edible Apple blog, this first model “wasn’t exactly a runaway hit as it was subsequently discontinued when the FCC found that it caused radio frequency interference problems.”

The model seen on Computer Chronicles came out in 1983 and resolved the FCC’s technical concerns. Nevertheless, it may have come to market too late. As another Apple blogger, AppleToTheCore, wrote in a 2013 post:

The Apple IIe was in full swing and the Macintosh with its full graphical user interface was picking up steam. Not to mention both machines had a mouse. Who needed a tablet?

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive, which provided a date of April 5, 1984.

- The YouTube channel RMC - The Cave managed to find a collector who owns some of the few Quantel Paintboxes still in existence.

- Pacific Data Images, whose early computer graphics work was featured in the B-roll, went on to do the first 3D animation for “The Simpsons” in 1995 and later became DreamWorks Animation.

- Aaron Marcus and Associates, the consulting firm that employed Michael Arent at the time of this episode, is still in business. In fact, Arent was the first employee hired by Aaron Marcus when he started his firm in 1982.

- Unfortunately, I was not able to find any information about the fourth guest in this episode, Ann Chase.

- The IRIS 1400 was a whale of a machine. The main cabinet weighed 200 pounds. The monitor and peripherals added another 100 or so.