Computer Chronicles Revisited 16 — The Apple Logo Programming Language

Today, Python is probably the most popular computer programming language taught in elementary and secondary schools. (There’s even a terrific podcast, Teaching Python, on this subject.) But back in the 1980s, BASIC was the language of choice for many introductory computer classrooms. Specifically, versions of Microsoft BASIC came with many popular 8-bit microcomputers, including the Apple II and Commodore 64, which were also commonly used in schools at the time.

However, BASIC was not the only educational programming language of the 1980s. There was also Logo, a language first developed in the late 1960s and modeled on an even older programming language, Lisp. Logo was especially popular in schools because of its use of graphics. This next episode of The Computer Chronicles provides an overview of Logo as part of a broader discussion into the use of computers in education.

The Computer Terminal as “Private Tutor”

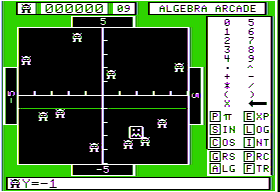

Stewart Cheifet and our old friend Herb Lechner opened this episode by demonstrating an educational game, Algebra Arcade by Wadsworth Electronic Publishing Company, on an IBM Personal Computer. Cheifet explained the game was designed to teach students algebraic expressions and their graphical representations. The game presented the player with a pair of axes and a number of “algebroids” positioned throughout the graph. The test for the player was to write an equation using algebraic functions to try and plot a graph that would intersect as many of these algebroids as possible. There was also a “graph gobbler” the player needed to avoid. If the final equation hit the gobbler, the player received a penalty.

With respect to the broader subject of computers in education, Cheifet pointed out that some people were afraid of technology and feared that computers would replace teachers and dehumanize education. Did Lechner see that in the future? Lechner noted that the expectations for the use of computers in schools was very high. But in practice, it had not been nearly as extensive as expected, and he did not think the positive or negative impacts so far had been terribly significant.

Cheifet then narrated our usual B-roll, this time taken at the Lucille M. Nixon Elementary School in Palo Alto, California. Cheifet said that with over one-half of U.S. schools now equipped with computers, students from elementary school through college were likely to have some computer instruction at every level of their education. But there were still doubts over the best way to integrate computers into a traditional curriculum.

Replacing the teacher with a computer terminal changed the focus of learning away from the instructor and to the computer. While this diminished traditional contact between the student and teacher, the terminal became a kind of “private tutor,” adjusting to the different learning rates and abilities of each student. The computer was also interactive, demanding answers within a specific length of time, making corrections, and helping the student to understand the reasons behind the mistake.

Cheifet explained that programming languages for children relied on colorful graphics and game-like approaches to teach children analytical skills and problem-solving logic. This meant that for younger children, time spent at the terminal could seem more like a game than a lesson.

The primary use of computer instruction was for rote learning and practice drills, Cheifet said. But there was another level of applications that demanded much more creative interactions. Programming languages like Logo were designed to teach children to make up their own programs, create their own commands, and in general put students in the active role of controlling the machine instead of just responding to an electronic inquisitor. Cheifet said proponents of this approach claimed that students trained to think logically would become better at problem solving in general. But at least one study questioned whether there was any difference between a Logo-trained and a traditionally trained child.

A 1.5-inch Rolls Royce That Only Costs $2.50!

For the first guest segment, Cheifet and Lechner welcomed Professor Patrick Suppes of Stanford University and Nancy Palmer, the computer education coordinator for the Palo Alto School District. Lechner repeated his earlier observation that the application of computers in education was not moving along as rapidly as everyone had hoped. How did his guests feel about that assertion? Suppes said that for most of the past 20 years that he’d been involved with computers and education, he agreed that was true. But in the last 3 or 4 years, he said the pace had really changed. There was now a lot of hardware and an increasing amount of software in the schools.

Palmer concurred, at least with respect to her school district. She said there was now a lot more interest from the teachers, and they were starting to use computers within their classroom in a lot of different ways. Students were using word processing and some other types of programs like data management, making the computer more of a tool. Of course, students were also learning programming languages like BASIC, Logo, and Pascal. But there was now a wider application of computers. Suppes emphasized that we had only really begun to integrate computers into education.

Lechner asked what triggered this movement of the past few years. What was different now versus 10 years ago? Suppes said it was primarily the enormous reduction in the cost of hardware. Palmer added it was also changes in the technology itself, notably the creation of the microcomputer market over the past eight years. That made computers a lot more reasonable for schools to buy and use. And as the technology improved, so did its ease of use. Suppes repeated a joke he’d heard that if cars followed the same trail as computers, a Rolls Royce would cost $2.50 and be just 1.5 inches long.

Cheifet then asked Suppes about his own work using computers to teach his introductory logic course at Stanford. How did that work? Suppes explained that he did not give any lectures for the course. Nor were there any assigned textbooks. Instead, students used computer terminals to review course materials and complete exercises. The students were free to come and go as they wished 24/7, although a teaching assistant was available every Saturday night from 8 to 11 p.m. Suppes said this provided many advantages from the student’s standpoint.

Cheifet asked about the instructor’s standpoint. Was this actually providing a better education? And did you pay a price for this type of convenience? Suppes said he didn’t think anyone was paying a price, but of course there was always some give-and-take with any approach to instruction. In this case, it was not just about the freedom the students had to come and go, but also the individualization. Some students just learned the topic much more easily and quickly than other students. With computer-based instruction, this individuality was taken into account, i.e., the pace of one student did not affect the pace of another student, which was not the case in a traditional classroom setting.

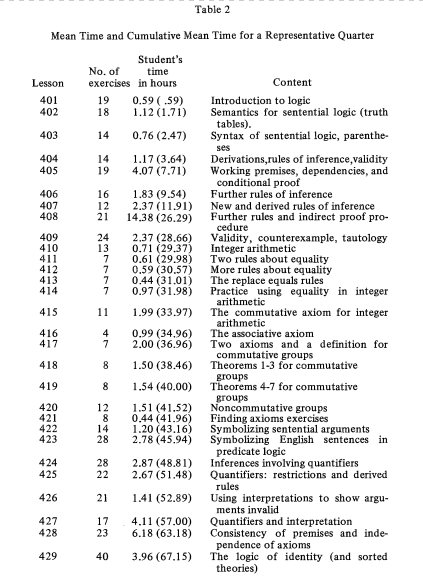

Suppes also emphasized his approach afforded students excellent opportunities to practice–and be corrected–in performing logic exercises and giving proofs and counter-examples. Suppes then provided a demonstration of his actual course using a terminal tied into the Stanford mainframe. Suppes noted it took a student about 75 hours to complete the entire course. (The image below is from a 1980 article that Suppes published on his course, and the mean time it took students to complete his course and each individual lesson.)

After the demonstration, Cheifet turned to Palmer and asked her if high schools were using computers to teach actual classes like this, or if they were just used to teach programming. Palmer said they were used in both ways in Palo Alto. For example, business classes used computers to teach accounting. Lechner asked if the computers made any difference. Were the achievement scores going up for the classes using computers? Palmer said that was difficult to answer in terms of real data. She felt there had been a difference with the students, but they were not at the stage where hard data has been collected.

“It Seems a Bit Whimsical. What’s the Big Deal?”

For the final segment, Glenn Kleiman joined Cheifet, Lechner, and Suppes. Kleiman owned Teaching Tools, Inc., and had recently authored a book on computers in education, Brave New Schools. Cheifet asked Kleiman to talk about the significance of the Logo programming language. Kleiman said Logo had been widely touted as the language to introduce kids to computers, even over BASIC. He added there had been a lot of other claims made about Logo, such as that it was an ideal way to teach problem-solving skills, although he did not necessarily buy into that hype. Nevertheless, he felt Logo had a number of advantages for introducing kids to programming, and it did have some implications for more general problem-solving skills.

Kleiman was there specifically to demonstrate Apple Logo on an Apple II. (As with BASIC, there were a number of different implementations of Logo targeting specific machines.) Kleiman explained there were actually two main components of Logo. The first, which was very well known, was turtle graphics, which was widely used with children. The other component involved list processing, which enabled Logo to work with words, sentences, and other types of things. But it was really turtle graphics that most students associated with Logo.

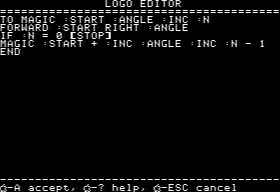

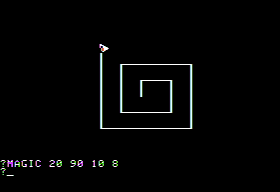

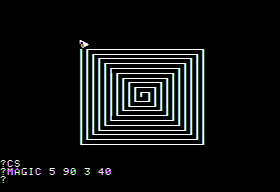

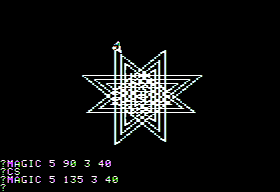

Kleiman explained that with turtle graphics, you could instruct an on-screen pen–the “turtle”–to move forward, turn right or left by a number of degrees, and mark its trail to create graphics. Turtle graphics allowed students to take these very simple commands and combine them into more complex programs called procedures. Kleiman demonstrated a sample procedure called “MAGIC” that he had created.

Rather than just try and describe all this–or display blurry screenshots from the episode–I went ahead and installed an original version of Apple Logo on an Apple IIe emulator and recreated Kleiman’s MAGIC demo. First, I typed the MAGIC procedure into the built-in Logo Editor:

Here’s a printout of the source code:

TO MAGIC :START :ANGLE :INC :N

FORWARD :START RIGHT :ANGLE

IF :N = 0 [STOP]

MAGIC :START + :INC :ANGLE :INC :N - 1

END

Basically, this procedure creates a new word–MAGIC–that Logo can recognize. The items preceded by colons are variables. The user invokes MAGIC by entering four variables–start, angle, increment, and N. The procedure then moves the turtle forward by start number of steps, turns the turtle to the right by angle degrees, and then moves the turtle forward again, this time by adding the increment to the previous start. This sequence is then repeated for N number of turns.

These are the examples presented by Kleiman that I recreated:

? MAGIC 20 90 10 8

? MAGIC 5 90 3 40

? MAGIC 5 135 3 40

Cheifet snarked that while this was kind of interesting, and it was fun to see these pictures, “it seems a bit whimsical. What’s the big deal?” Kleiman conceded it was perhaps whimsical in a way. But kids enjoyed whimsy. He thought the “big deal” was that it was a very different approach that what Professor Suppes had demonstrated earlier. Suppes used computers to do things that had always been done in education–tutorials and drills. And that was certainly a valid use of the technology, Kleiman said. What Logo provided, however, was an example of introducing a tool that kids could explore, where the child had more control than the computer. This was not about problems and questions coming out of the computer–the computer was waiting for the child to act.

Cheifet asked Suppes for his view of this use of computers versus his work. Suppes said he agreed with Kleiman that the use of Logo could be valuable and fascinating for young students. The nice thing about Logo was that it gave students a quick and easy sense of how a computer language worked.

Cheifet wanted to know if there were social–or perhaps anti-social–consequences to coupling kids with machines rather than traditional “flesh and blood” teachers. Suppes said it was important to consider different use cases. In the elementary school it was very important for the student to have a personal relationship with the teacher. Indeed, one of the paradoxes of American education was that while the data overwhelmingly showed this relationship was critical, class sizes on average were larger in elementary schools than in secondary schools. But as students became adults, Suppes said they were in a different kind of world. He said many adults in the future might want to get a good deal of their education at home over a terminal, because it was inconvenient to go to a campus site.

Lechner followed up, asking if in the future he thought it was possible an entire curriculum could be taken by a mature student over a computer. Suppes said sure, and his own courses at Stanford were meant to serve as an example. The socially important thing was teaching courses this way allowed for decentralization. It was really a social, administrative, and psychological decision rather than a technical decision.

Kleiman said he took a somewhat different view. He saw computers mainly as a tool for the teacher to use. He did not think computers were capable of replacing teachers. Kleiman noted he actually took Professor Suppes’ logic class the first year it was offered by computer. Kleiman said he thought the computer provided a good means for practicing logic, but there was an intelligence and intuition to the subject matter that one could get from a professor of Suppes’ caliber better than any computer program.

Patirick C. Suppes (1922 - 2014)

Patrick Suppes passed away in November 2014 at the age of 92. According to his New York Times obituary, Suppes joined Stanford University’s philosophy department in 1950 and remained with the school for the next 64 years until his death. During his extraordinary tenure, the Times noted, Suppes “influenced a wide range of academic fields, among them logic, physics and psychology.”

Suppes was one of the earliest promoters of using computers in education. In a 1966 paper, the professor discussed his earliest experiments into computer-assisted instruction. One such experiment involved “tutorial sessions” for young children, who used a light pen with a CRT monitor to learn basic vocabulary:

With such a tutorial system we can individualize instruction for a child entering the first grade. The bright child of middle-class background who has gone to kindergarten and nursery school for three years before entering the first grade and has a large speaking vocabulary could easily finish work on the concepts I have listed in a single 30-minute session. A culturally deprives child who has not attended kindergarten may need as many as four or five sessions to acquire these concepts. It is important to keep the deprived child from developing a sense of failure or defeat at the start of his schooling. … It is equally important that a tutorial program have enough flexibility to avoid boring a child with repetitive exercises he already understands.

Closer to the time of his Chronicles appearance, Suppes presented another paper, “Computers and Education in the 21st Century,” which spelled out his long-term vision for what the world would look like in 2084. He continued to iterate on the importance of individualization and predicted that computers would eventually make traditional secondary schooling obsolete:

Schools will be close to where adolescents are living. Teachers will be like tutors, but not like the tutors in ancient Athens in the sense that that they will not be carrying the full load of the instruction. Teachers in secondary schools will be counselors and trouble shooters, not just counselors about future careers or emotional problems, but cognitive counselors, able to help when a student has not found the right mix or the right approach to instruction in the wealth of technological offerings. The demands on the teachers will be greater than they are now. They will need to be more professional and more deeply trained, and they should be paid much better than they are now. The expert teachers I see as needed in the technological setting of the secondary school in 2084 must be technically expert and intellectually sophisticated. They should be compensated accordingly.

Logo or BASIC?

Glenn M. Kleiman also found a home in academia. As mentioned above, he attended Stanford and took Professor Suppes’ logic class in the 1970s. After receiving his doctorate in cognitive psychology from Stanford in 1977, he founded the aforementioned Teaching Tools company in 1981. After four years of independent consulting and software development, Kleiman joined the non-profit Education Development Center, where he served in various roles over the next 22 years. During this time, he also lectured at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

In 2007, Kleiman joined North Carolina State University as the executive director of its Friday Institute for Educational Innovation. He stepped down as executive director in 2018 but remains on faculty as a professor.

As his Chronicles appearance illustrated, Kleiman was a cautiously optimistic supporter of Logo. In an article from the July 1982 issue of Compute!, he compared the relative strengths and weaknesses of the newer Logo versus the older BASIC. Kleiman was measured in his praise for the latter, however, noting that many Logo advocates insisted it was “the only proper approach, and that teaching BASIC is almost evil.” Kleiman argued it was not that cut-and-dry:

While the turtle graphics component of Logo suits children very well, I am less certain about the rest of Logo. The commands for working with words are powerful but may not be simple for children to use. Most teachers using Logo have so far focused on using turtle graphics. I am waiting for more information from teachers and children who are exploring the non-graphics aspects of Logo.

In BASIC, children generally find it easy to understand the individual string processing commands and to write small programs with them. However, the difficulty of BASIC programming increases rapidly as the size of the program increases.

Kleiman’s conclusion at the time was that it did not matter which language children learned. The more important question was “whether the teaching encourages careful task analysis, problem solving, and testing.” In that sense, he thought Logo, which encouraged “modular programming,” had the advantage over BASIC. He added that turtle graphics also had the side benefit of teaching children about geometry and symmetry.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was recorded in late 1983 or early 1984. I could not nail down the date with any greater accuracy.

- Much like BASIC, there were several different implementations of Logo, even within the same platform. For instance, Kleiman’s Compute! article noted there were at least two distinct versions available for the Apple II: one by Logo Computer Systems, Inc. (LCSI), and the other by MIT. Apple marketed LCSI Logo, while two outside companies sold the MIT version. (In my emulation re-creation, I used Apple Logo II, an LCSI release from 1984.)

- According to Kleiman, the various Logo packages sold for between $169 and $179 as of late 1982. You could also buy a program called Nibble, which provided just a simplified version of the turtle graphics package, for around $30.

- The only commercial software ever produced by Teaching Tools, at least according to Moby Games, was Word-a-Mation, an educational game written by Kleiman for the Apple II.

- Unfortunately, I was unable to track down any verifiable information regarding Nancy Palmer or her current whereabouts.

- The American Philosophical Society named an award for Professor Suppes. The Patrick Suppes Prize is actually a multi-disciplinary award that rotates its recipients among the fields of the philosophy of science, the history of science, and psychology. This year’s recipient (for the history of science) is Professor Jessica Riskin of Stanford University.

- I mentioned Python as the successor to Logo when it comes to teaching today’s students about computer programming. There is actually a turtle graphics package available as part of the Python Standard Library. Episode 10 of Teaching Python podcast, presented by Sean Tibor and Kelly Paredes, does a deep dive into this modern-day reimplementation of Logo.

- To be honest, I never knew about the non-turtle graphics part of Logo until I watched this episode. Like many elementary school computer students in the late 1980s, we were mostly taught BASIC with the occasional detour into Logo’s turtle graphics.