Computer Chronicles Revisited 15 — Space Shuttle, Excalibur, Pinball Construction Set, and Dr. J vs. Larry Bird

Even if you’re only a casual gamer, there are probably a few video game designers whose names you’re familiar with, such as Sid Meier, Todd Howard, and Shigeru Miyamoto. From the early days of computer gaming, there was a concerted effort to promote certain “superstar” designers to help personalize and sell games to the public. This next episode of The Computer Chronicles featured three such designers from the early 1980s, as well as an executive whose name would become synonymous with computer and video game production in the decades that followed.

From The Claw Machine to Dragon’s Lair

Computer games were the overall subject of this episode. Stewart Cheifet and Gary Kildall opened by demonstrating the “granddaddy of computer games,” Atari’s Pong. Cheifet noted that games were an important part of launching the growth of the personal computer market. Kildall agreed it was “certainly a part of it,” adding that many personal computers like the Apple II offered color bitmap graphics. This allowed game designers to do dynamic things that were not possible with the teletype and scrolling displays used on older computer systems.

Cheifet then narrated the obligatory B-roll for the episode, which briefly sketched the history of computer gaming from the penny arcades of the early 20th century, which offered “simpler, more mechanical amusements,” such as the claw machine. Like today’s computer games, a player needed manual dexterity in competing for points and rewards. But computer games brought a level of fantasy that no mechanical game could match. Instead of escaping from a school room or an office, Cheifet said a computer game allowed the player to “leave the earth” or move to a different universe. And modern computer games offered different kinds of challenges from fast action games to maze-type games and even wargames.

Cheifet noted that in one of the latest adventure games–which he didn’t name but appeared to be Dragon’s Lair–animated images were stored on laserdisc and recalled in sequence following a specific story, but also took into account the player’s responses. If the player moved the stick in the right direction, they would be rewarded with a successful escape. But if the player made a mistake, the game would show an alternate video sequence.

Just Like Flying a Real Space Shuttle

For the next segment, game designers Jessica Stevens and Chris Crawford joined Cheifet and Kildall. Kildall opened by asking them to clarify: Did they call themselves “designers” or “programmers”? Crawford said he called himself a designer since most of the “sweat and blood” occurred during the design phase and not the programming phase. He said he spent a great deal of time worrying about what his audience would experience in the game, and only towards the end of the project did he actually write code.

Kildall asked what elements made a game design interesting. Crawford said that depended on what he was trying to accomplish. He started by setting a goal, i.e., what effect he wanted the game to achieve. He wanted to somehow communicate a message to the audience. That message then dictated the topic and style of the game.

Cheifet observed that Crawford sounded more like a writer than a computer programmer. He asked Stevens if that’s how she saw herself as well. Stevens agreed with that characterization. She said they were writing a type of novel, creating a vicarious universe within the computer program. They had to model everything they wanted and put every small detail into the game. Stevens noted that for her game, Space Shuttle: A Journey into Space, she put in a year-and-a-half of research to understand the subject before distilling the important aspects out and putting it onto the cartridge.

Stevens then provided a demonstration of Space Shuttle on an Atari 2600. The game opened with an automated demo of a space shuttle flight, which was based on the real second mission of the Space Shuttle Columbia in November 1981. The goal was to launch the space shuttle, connect to an orbiting space station (based on Skylab), and return to Earth for a landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Stevens also pointed to the various real-life details in the game, such as the “yellow flash” the astronauts see after jettisoning the shuttle’s solid-rocket boosters.

Cheifet said it was incredible Stevens could do all this on an Atari 2600, which was not even a personal computer. How did she manage to squeeze the entire game to fit? Stevens said she had to model the universe and then fit everything piece-by-piece. She started with the basic mission and then added features and functions along the way. And in fact, she was not happy with her initial results–she still had a list of 146 separate items she wanted to include. So she spent three additional months adding them. The goal was to be as accurate and complete as possible. Kildall asked how big the final game was in terms of memory. Stevens said the game fit on an 8 kilobyte cartridge and took 13 months of programming.

Cheifet pointed out that one way Stevens adapted her game to the limited 2600 hardware was to make “functional” use of the console’s switches, which were normally reserved for system-level uses like game reset or selecting television type. Stevens said all of these switches were controlled by the computer–the Atari–so she redefined them to perform game tasks, such as operating the space shuttle’s engines or opening its cargo bay. All of these modifications made it necessary to include an overlay that fit over the console and served as a “cheat sheet” for the player. The game also had a 30-page instruction manual that provided the details on how to fly the space shuttle–basically, a small flight manual.

Cheifet noted that piloting a space shuttle was a difficult task. Could a child or a normal person actually pull this off in the game? Stevens agreed it would take an average person “years of work” to learn how to pilot the actual shuttle. But she also looked at how NASA trained its astronauts. They started with book exercises and watching film strips. Her game followed a similar approach. It began with watching a demo flight completely controlled by the console. This was essentially a film strip. Next, the player took a training flight, which compensated for user error and mimicked the simulators used by the real astronauts. The third flight was then the “real thing.”

Kildall said this was basically an educational game. Stevens described it as “vicariously educational.” The player wasn’t simply sitting there looking at flashcards. They were learning about one of the most technologically advanced items ever developed by humans. Once the player mastered the game they had effectively learned about what an astronaut did on a space shuttle mission.

Cheifet then shifted back to Crawford and asked about his own game, Excalibur, which was available on Atari’s 8-bit computer line. Crawford said the game was about “leadership.” His motivation was the 19th century Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz’s famous axiom, “war is a mere continuation of policy by other means.” Crawford said he was tired of wargames that glorified war. He wanted to how that war was sometimes unavoidable but must never be entered into cavalierly. So he wanted Excalibur to teach concepts of leadership.

In the game, the player assumed the role of King Arthur, who must unify Britain. Crawford noted that unification was different than conquest–the player had to convince people of their authority. That involved more than brute force. Cheifet clarified Excalibur was designed for the Atari 800. Crawford said yes, his game required 48 kilobytes of memory and a disk drive. The game actually required swapping multiple disks, as the total game included 66 kilobytes of object code written in assembly language.

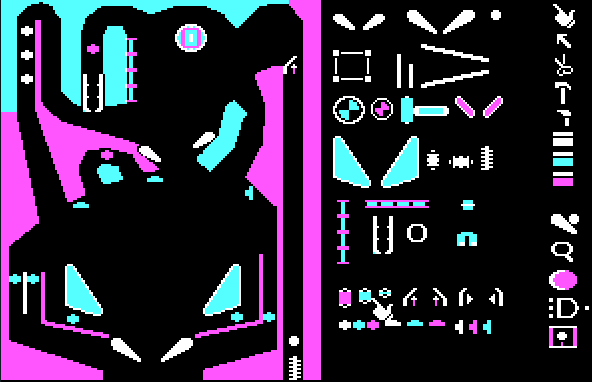

Electronic Arts: Simple, Hot & Deep

The final segment focused on Electronic Arts. The company’s founder and president, Trip Hawkins, appeared with Bill Budge, the designer of EA’s Pinball Construction Set (PCS). Kildall opened by asking what made a game successful? Budge said it was hard, given that you couldn’t just ask people what they wanted to see on the computer. The person writing the program had to have an “inner conviction” and write a program they wanted to use. Indeed, his goal when he started making PCS was just to get it to work. Kildall asked where he got the idea. Budge said it was a “funny, indirect process.” He was tired of simply playing games and he thought it might be fun to make a game where other people could write games. Kildall quipped this made PCS a “meta-game.”

Kildall followed up, asking if there was a special segment targeted by PCS. Budge replied it really was for the more “avant-garde” computer users. It took awhile for an audience used to games like Pac-Man to find PCS. His game did not register at first but the audience had started to grow to the point where they were now seeing good results.

Cheifet asked Hawkins what he looked for in a successful game from the business side. Hawkins said PCS was a good example of what he looked for, noting it was now one of the top-10 selling games according to Billboard. Overall, Hawkins said EA’s philosophy was to look for games that were “simple, hot, and deep,” which he broke down as follows:

- Simple meant the user did not have to read a lot of instructions; PCS allowed players to get started with pre-made pinball table or build one of their own.

- Hot meant the game should take full advantage of the computer’s sound and graphics capabilities.

- Deep meant letting the player “make their own game,” which helped to extend the life of the product and get people coming back to play again and again.

Budge then demonstrated PCS on an Apple II. The gameplay was based on using a joystick to move various pinball machine parts around to create a pinball machine. Budge joked that young children jut wanted to “grab a bunch of bumpers” and put them on the table, which serious pinball aficionados would scoff at.

Cheifet asked Budge about his next project or goal. Budge replied he wanted to extend the “construction set” idea further. The challenge would be designing the box of parts. With pinball that was relatively simple, as a pinball machine had a small box of parts. You didn’t need to think about more abstract concepts. But with a more general construction set, it was not even clear what the parts should be. Budge said it was almost like inventing a new language.

Cheifet asked Hawkins if computer games were here to stay, or if they would suffer the same downturn as arcade games, which seem to have peaked. Hawkins noted that computer games were fundamentally different video games, mainly because computer technology was more extendable. For example, all of EA’s games came on floppy disks, each of which held more memory than a coin-operated arcade machine. Indeed, you could get a program 3 or 4 times the size of an arcade machine on a computer disk.

Kildall noted that computer games had already advanced from “relatively unsophisticated” offerings to something that required a lot of programming. Cheifet said this was largely a function of having more memory available. Budge added it was also a function of people getting better at programming. Five years ago, he said there weren’t that many people writing computer games. Now there were thousands of people capable of writing a good video game. And a few designers had “upped the ante” to the point where it was not enough just to write a good game–you also had to include extra features like a game editor.

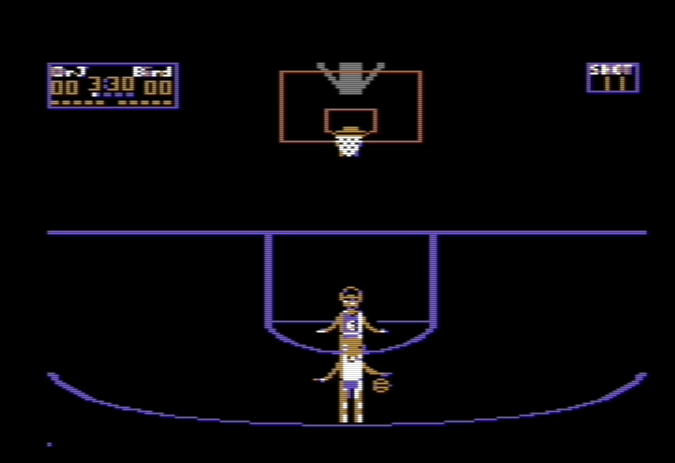

Hawkins then demonstrated the final program for the episode, One-on-One, a basketball game featuring the likenesses–well, I use that term loosely–of NBA players Larry Bird and Julius “Dr. J” Erving. Bird and Erving actively participated in the design process, according to Hawkins. Hawkins said there were photo sessions with both men to help “capture them in action.” EA designers talked to both players about “their moves,” and combined that with statistics–notably, the players’ shooting percentages from different parts of the court–to create the player models for the game.

Cheifet asked Hawkins about the “next generation” of computer games. Hawkins said at a simple level, the goal was to extend the realism and graphics seen in EA’s current products. He also pointed to “more creative possibilities for the player,” by extending concepts like PCS. In fact, EA had already launched Music Construction Set, which used a lot of Budge’s ideas from PCS. The greatest challenge moving forward was looking for original ideas that “broke the mold.”

Kildall ended the program by asking where those new ides came from. Did people just come to EA with them? Hawkins said it happened in many different ways. For instance, EA’s recent platformer Hard Hat Mack came from two high school students (Michael Abbott and Matthew Alexander) who drew up the idea on paper during their physics class. Hawkins said he signed a contract for the game based on that alone.

Tax Software Is Hot This Month!

Stewart Cheifet presented this episode’s “Random Access” segment, which is dated around the end of February 1984.

- Hewlett-Packard announced its new $500 portable printer, a non-impact inkjet model with low noise, battery paper, and the ability to print 150 characters per second.

- IBM announced a licensing deal with Intel to allow the PC manufacturer to make its own 8088 microprocessors. Rising demand on Intel had prevented IBM from producing enough PCs to meet market demand. IBM also obtained the rights to make its own 80286 processors for its planned next-generation model of the Personal Computer, currently nicknamed “Popcorn.”

- There were reports that United Kingdom-based Applied Computer Technologies would buy Victor Technologies and move the latter’s manufacturing operations from Silicon Valley to Scotland.

- Tandon Corporation, the largest manufacturer of disk drives, said it would lay off 1,000 employees and transfer its manufacturing operations overseas to cut costs. Cheifet noted this was part of a trend–in the past year, at least 20 countries had sent delegations to Silicon Valley to lure business abroad. Of those nations, Ireland had proven the most successful.

- The Japanese Diet was debating a bill that would limit copyright protection for U.S. software to 15 years.

- Cheifet said the “hot software” this month was tax preparation software, with 2 of the the more than 20 programs on the market–Continental’s Tax Advantage and Howardsoft’s Tax Preparer–breaking into the top-10 for the week.

- Computer magazines continued to boom, with Cheifet noting there were more than 300 now on the market. The fastest growing publications were Compute!, Personal Computing, Popular Computing (the sponsor of “Random Access”), and InfoWorld.

- Finally, Cheifet joked the last place you’d want to see a robot was a bar. But this past week in San Francisco, the world’s first robot bartender made its debut. The robot could talk, take orders, and mix 200 different drinks. Unfortunately, when a waitress asked for a Bloody Mary and a beer, the robot knocked a glass onto the floor and started pouring beer all over the counter. The robot’s designer acknowledged there were still some bugs to work out.

Paul Schindler on Communications Software

This “Random Access” segment also featured the first of many quick software reviews by Paul Schindler, a technology journalist then affiliated with the Whole Earth Software Review. In this vignette, Schindler actually provided an overview of communications packages. He noted that fewer than one-fourth of all personal computers could actually communicate with other machines. So he recommended the following software packages for those “looking to take the plunge”:

- for users of CP/M-based machines, MITE and MODEM7;

- for IBM Personal Computers, SMARTCOM 2, CROSSTALK 16, or PC TALK 3 (the latter being the cheapest at just $35);

- for Apple users, TSC Terminal (for 40-column screens) or Data Capture 2 (for 80-column screens); and

- for Commodore & Radio Shack computers, VIDTEX.

Stevens Caught in Apple Crossfire

The three “superstar” game designers featured in this episode all had interesting post-Chronicles careers. Jessica Stevens, however, made her mark largely outside of gaming. At the time she designed Space Shuttle, she ran her own company, Woodside Design Associates, Inc., which described itself as a “high technology think tank.” Stevens basically developed her game as an outside consultant for Activision. She also ported the game Carnival to the Atari 2600 for Activision.

Stevens and Woodside Design’s real focus was developing flat-panel display technology. This led to the demise of Woodside in the late 1980s. Stevens had struck a verbal agreement in February 1985 with Steve Jobs to have Apple buy Woodside for $5 million and then spend another $20 million to develop flat-panel displays for a “book-size Macintosh” project that Jobs was pushing. Unfortunately, the day the deal was to be signed, Jobs and Apple President John Sculley’s infamous feud came to a head, which ended with the company’s board firing Jobs. Sculley then abandoned Jobs’ plan to develop a Mac with a flat-screen and scuttled the deal with Stevens. Woodside Design then filed a $1 billion breach of contract lawsuit against Apple. I couldn’t find any information on the outcome of that suit, but I’m guessing it never went anywhere.

Stevens founded a new company, Telegen Corporation, in 1990, which also focused on flat-panel display technology. The company went public with Stevens serving in various executive roles up until the company’s bankruptcy in the early 2000s. The last corporate filing from Telegen, with Stevens serving as CEO, was filed with the SEC in January 2003.

Crawford Rejected Computer Games for Lack of Artistic Merit

Chris Crawford developed a number of games while working at Atari from 1979 to 1984. His most notable project was Eastern Front (1941), a turn-based wargame for the Atari 8-bit computer line. After that game became a best-seller, Atari promoted Crawford to manage its games research group, during which time he developed Excalibur.

The North American video game crash of 1983 led Atari to lay off a good chunk of its workforce, including Crawford, who went out on his own as an independent developer. He created Balance of Power, a Cold War political simulation, for the Macintosh in 1985. Crawford said this was his most commercially successful game, selling 250,000 copies.

But commercial success was not Crawford’s main objective. He cultivated a reputation in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a fierce critic of the games industry, arguing that designers should promote gaming as a medium of artistic expression rather than entertainment. Crawford founded and published The Journal of Computer Game Design from 1987 to 1996, which featured a number of editorials in which he spelled out his problems with the industry. For instance, in the October 1991 issue, he argued:

Art is an expression by the artist; entertainment is an expression for the audience. The artist is primarily concerned with himself; the entertainer is primarily concerned with his audience. The artist seeks to express the truth within himself; the entertainer seeks to give the audience what it wants.

Entertainment is therefore intrinsically commercial and art is just as intrinsically noncommercial. You can sell entertainment and you can’t sell art. (It’s true that snobs will pay a lot of money for your art, but only after you’re dead.)

Having said this, I can now state that almost nothing in the computer game industry comprises art. We are an entertainment business.

Famously, Crawford delivered what became known as the “Dragon’s Speech” at the 1992 Computer Game Developers Conference, an event that he had created in 1988. This speech marked Crawford’s exit from game development in favor of what he dubbed the next generation of “interactive storytelling.” To that end, Crawford changed the name of his publication to Interactive Entertainment Design in 1993 and began work on a new game engine, Storytron, and an associated game, Siboot. But after more than two decades, he failed to make much progress with either. Crawford later explained why he was giving up on interactive storytelling:

My goal all along has not been to create a single great piece of interactive storytelling; it has been to ignite a new industry, a community devoted to the furtherance of interactive storytelling as an art form. Suppose that I could indeed finish Siboot to my own satisfaction. What would happen?

First, few people would appreciate it. They would judge it by the only standards with which they are familiar: the standards of current game design. They would conclude that Siboot is a lousy game — and they would be right. Siboot was never intended to be a game; it’s interactive storytelling. The emphasis is on character interaction, and it already offers interesting dramatic character interaction. But people aren’t looking for interesting dramatic character interaction; they’re looking for the things that make great games: challenge, a smooth learning curve, impressive graphics, catchy little tunes to accompany their play. Above all, a game must be winnable. Yet stories aren’t necessarily about winning and losing; they’re about drama.

Budge Went from Construction Sets to Building Web Browsers

Our final designer, Bill Budge, seems to have had a much less dramatic career than Crawford. Budge never did make the more abstract construction set he mentioned to Setwart Cheifet. But he did go on to write MousePaint, a popular drawing program for the Apple II.

Budge later joined Trip Hawkins’ other venture, The 3DO Company, where he served on the engineering team for nine years. Budge then returned for a brief stint at EA in 2003, working on the company’s game based on The Godfather. After that, Budge worked at Sony. He joined Google in 2010 as part of the Chrome web browser team. In January 2022, Budge announced his retirement from Google.

Like Budge, Trip Hawkins worked at Apple prior to the latter founding Electronic Arts in 1982. Hawkins remained at the helm of EA until 1991, when he started 3DO, which marketed its own video console under that same name from 1993 to 1996. When the 3DO console failed to take hold, the company transitioned to simply developing games. Hawkins remained CEO until the company’s bankruptcy in 2003. That same year, Hawkins founded Digital Chocolate, a mobile games development company, which lasted until 2014.

Pushing the Limits of 1984 Gaming Capabilities

Space Shuttle and Excalibur were both fairly sophisticated games for 1984. Dan Persons’ review of Space Shuttle in the April 1984 issue of Video Games went so far as to say this was “not a game,” but a “full-fledged, strikingly accurate simulation of a mission into space.” Persons noted Space Shuttle was “mind-bogglingly hard,” but that was probably because “space travel is hard.” It was also not a quick game, as Persons observed it took him a “full half hour” to dock the space shuttle with the orbiting satellite, and “thirty minutes to dock with two more.”

Excalibur reviewers were also quick to note that game’s difficult learning curve. According to David Duberman’s review in the February 1984 issue of Antic, Excalibur was “perhaps the most complex [game] yet written for an eight-bit computer!” It was “impossible to play Excalibur with the minset you might use for a game of Pac-Man, for example.” Duberman noted the game came with a 100-page manual, which included a 69-page novel that the player would probably need to read multiple times to understand and complete the game’s objectives.

As Crawford mentioned during his Chronicles segment, the large size of Excalibur required switching between multiple disks. David P. Townsend explained in his review for Computer Gaming World:

The game itself is divided into three modules, Camelot, Britain, and Battle. The importance is that only one can be in memory at a time, so when you move from one module to another you must wait for the computer to swap the current module out to disk and bring the new module into memory.

Crawford himself included a “designer’s note” to accompany Townsend’s review. Perhaps not surprisingly, he is equally complementary and critical of his own creation. While saying he felt “deep pride in this game,” he nevertheless found it was “still too ‘wargamy’ for my taste.” He also lamented the lack of commercial success, complaining that his “magnum opus” had “not won the attention I think it deserves.”

Larry and Dr. J Make EA a Sports Powerhouse

In contrast to the more esoteric offerings from Stevens and Crawford, the two Electronic Arts games proved to be much more accessible commercial hits. Elaine Holden praised Pinball Construction Set in the January 1984 issue of Byte magazine, noting, “It’s really hard to find anything wrong with this game.” She cited Budge’s “marvelous sense of programming” and credited him with creating a “classy game” that was simple to grasp yet still fun “for even the most advanced player because of the challenge and the endless variety of modifications, refinements, and degrees of difficulty available.” And unlike Excalibur and its novel-in-a-manual, PCS only came with a 13-page users guide.

One-on-One enjoyed similar praise. A review in the March-April 1984 issue of St. Game declared it “the sports game of 1984.” The reviewer said that “[e]ven nonathletes have a fair chance at beating the computer or another player, but knowing a little about real-life basketball doesn’t hurt,” given the game’s accounting for the real Bird and Erving’s “respective strengths and weaknesses.” The game’s designer, Eric Hammond, was also described as a “formidable basketball player himself.”

The game itself was a landmark in that it was the first to feature real-life professional athletes. Patrick Sauer, in a 2017 retrospective for Vice, noted “the game was a huge financial boon for EA Sports”–selling over a million units according to Trip Hawkins–“but the biggest payoff was in how it shaped the company.” Indeed, Bird and Dr. J helped pave the way for another, more lucrative EA sports franchise–the John Madden football games.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode was recorded on February 28, 1984, and is available at the Internet Archive.

- Dragon’s Lair was directed by famed animator Don Bluth, perhaps best known for his 1982 film The Secret of NIMH . If you’d like to learn more about Bluth and the Dragon’s Lair game franchise, I recommend this episode of the Don Bluth-focused podcast The Bluth, the Whole Bluth, and Nothing But the Bluth, hosted by Dax Schaffer and Sara Iyer.

- Jessica Stevens’ brothers, Garry Kitchen and Dan Kitchen, are actually better known in the world of game design. The Kitchen brothers worked for Activision in the early 1980s, where they created and ported a number of games for the Atari 2600. They both continue to work in the field today.

- EA apparently only released one other game around this time with “Construction Set” in the name: Stuart Smith’s Adventure Construction Set.

- According to the Vice article, Julius Erving and Larry Bird each received $25,000 for participating in the design of One-on-One as well as 2.5 percent royalties on sales; Erving also received some EA stock.

- The IBM “Popcorn” would be released in August 1984 as the IBM PC AT.

- Applied Technology did not end up buying Victor Technologies. Instead, Sweden-based Datatronic AB purchased 90 percent of Victor, which was in Chapter 11 bankruptcy, in August 1985.

- The robot bartender mentioned by Cheifet actually ran off of an Apple II computer.

- Although Cheifet noted there was an ongoing boom in computer magazines, the Whole Earth Software Review that employed Paul Schindler was not among the more successful ones. It only produced three issues in 1984 before merging with another publication under the name the Whole Earth Review, which published quarterly until 2003.