Computer Chronicles Revisited 5 — Concurrent CP/M, MS-DOS & UNIX

The first season of The Computer Chronicles was repackaged and marketed to educational institutions as The Computer Chronicles Telecourse. The recording we have for this next episode, and a few more going forward, were part of that telecourse and thus included a series of interstitial segments hosted by SRI International’s Herbert Lechner, whom we met in the first broadcast episode. Lechner’s segments mostly review the key concepts discussed in the regular episode and refer to an accompanying textbook for students to follow. I won’t be discussing Lechner’s segments during my episode recap, as it would be little more than summarizing his summaries, which would be redundantly redundant.

Operating Systems Are “Most Exciting When They Don’t Work”

Lechner also appeared this week as Stewart Cheifet’s co-host. Cheifet opened the program by explaining Lechner was “sort of sitting in for Gary Kildall.” In fact, Kildall was one of this week’s guests, as the subject was operating systems, and he created CP/M, which Cheifet described as “perhaps the major operating system in use today.”

Cheifet noted that operating systems were a tough subject to discuss. Every user dealt with an operating system, but most do not understand them. Lechner pointed out that operating systems are “most exciting when they don’t work,” and that’s obviously not something you want to see as a user. Lechner then provided a brief overview of operating systems, explaining they manage the computer’s resources and save the individual programmer “a lot of nitty-gritty effort” by providing platforms to make applications that can run on a number of machines with different configurations. And when it comes to larger machines, the operating systems have become “very sophisticated” and can manage resources in such a way as to help the computer achieve its full potential.

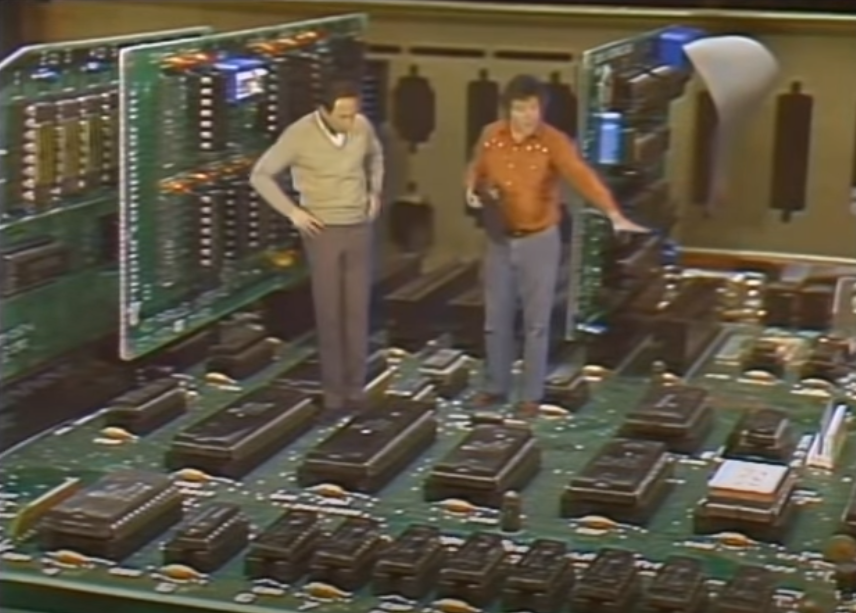

The episode then veered into a very unusual segment–at least by Chronicles standards up this point–with a business-casual Stewart Cheifet appearing to walk inside pf the enlarged interior of an Apple IIe. Cheifet greeted another man, Apple engineer Bruce Tognazzini, who explained that he’s just “checking things out” with the computer before the user turns it on. (In a testament to how silly this sketch was, Tognazzini then looks at his wrist to check his non-existent watch.) Cheifet asked Tognazzini to explain what they appear to be standing in. Tognazzini explained it was the parts that make up an Apple IIe: The microprocessor, which is the heart of the computer; read-only memory (ROM) chips that contain the operating system kernel and the BASIC programming language; and eight random access memory (RAM) chips that hold information retrieved from the disk drive.

Cheifet then asked Tognazzini to explain in greater detail what the operating system does. Tognazzini replied the operating system starts to run when the user turns the computer on. (Tognazzini said the Apple IIe only used 12 volts of power when active, so he and Cheifet were in little danger of electrocution while “standing inside” the unit.) After the power is turned on, Tognazzini said the processor checks itself out before turning things over to the ROM, which has a small program that looks for a disk controller. The disk controller, in turn, has its own ROM that takes control and brings in the operating system from the disk inserted in the drive through a white cable. The operating system then takes up about one-fifth to one-fourth of the available RAM in the Apple IIe, including the BASIC programming language. After about 15 to 30 seconds, the screen displays a message informing the user they can get to work. The segment itself then ended with a pullout to the Apple IIe monitor, which displayed, “DOS ERROR – WARNING! – TWO MEN INSIDE.”

Would CP/M Remain “Simple, Clean, and Neat”?

In the next segment, Gary Kildall and Tony Fanning, a member of the corporate engineering staff at Hewlett-Packard, joined Cheifet and Lechner. Lechner asked Kildall, the CEO of Digital Research, to explain how he got started making operating systems. Kildall said that even though he was now known as an “OS guy,” he actually started out as someone primarily interested in programming languages. During the early days of microprocessors in the 1970s, Kildall worked with Intel on a programming language for microcomputers called PL/M. It then became necessary to develop some sort of operating system to support that language, which led to the creation of CP/M, or control program for microcomputers. He noted that prior to CP/M, programming in PL/M required the use of paper tapes. CP/M allowed for the use of floppy disks in smaller computers.

Cheifet reiterated his point from the introduction that operating systems remained a “mystery to many computer users,” who may take advantage of its features but never delve into the inner workings. Kildall offered his own take on what an operating system does, noting there were basically three levels of software in a personal computer: Machine instructions, system software, and application software. The latter was what users actually went out and purchased in the store. Operating systems provided the system software, or the “middle layer” between the applications and the machine instruction. The OS thus principally served as a “traffic cop” that kept track of tasks like storing files and handling input and output.

Cheifet then turned to Fanning and asked what he looked for in an operating system as a user. Fanning said he never wanted to “see” the operating system. He just wanted to use applications. What you look for in an OS therefore depended on what you were trying to do. If his goal was to use a word processing program, for example, then he just wanted the operating system to “disappear” and not bother him.

Cheifet noted that Fanning worked primarily with MS-DOS. He asked Fanning to explain how that operating system differed from CP/M. Fanning said in a lot of ways, they both did the same types of things: MS-DOS also took care of files, managed data transfers, and provided a “human interface” for the computer.

Returning to Kildall, Cheifet pointed out there had now been “several generations of CP/M” released. So what was added with each new generation–i.e., how did you actually “improve” an operating system? Kildall replied the real key was to match what you were doing with the capability of the computer system available. He noted that in the early days of microcomputers, the storage capacity was limited to 16 kilobytes (KB) of RAM. With such limited space, you needed to tailor an operating system to only use a small portion of that memory. But when you start to add more memory and faster processors, then you can add more functionality to the operating system. For instance, modern 8-bit systems now have a maximum possible RAM of 64 KB. And 16-bit computers come standard with 128 KB–moving towards 512 KB. So again, the operating systems will expand and add functions that take advantage of these larger memory sizes.

Lechner said one of the early attributes of CP/M was that it was “simple, clean, and neat.” Now that computers were much larger, would we also see the complexity grow? Kildall said it was “very easy to add bells and whistles” to an operating system that do not provide any additional functionality. The question was therefore how to add the “right kinds” of functions. He said that on the newer 16-bit machines a key feature was concurrency, also known as multi-tasking. Early microcomputers were only capable of performing one task at a time. But now a 16-bit machine could do something like print a document while continuing to run a word processing program.

Cheifet then asked Kildall to demonstrate his Concurrent CP/M operating system on an IBM PC. Kildall explained that Concurrent CP/M was a “real-time system” that could switch between programs at short time intervals. This allowed for up to four virtual consoles, each of which could run a separate program. In a business environment, Kildall said this would enable the user to run a word processor on one screen and then switch to a second screen to run spell-checking software or receive data over a modem. The user effectively had “multiple systems on your desk.” Kildall said concurrency was where operating systems were moving towards given that newer microcomputers had at least 512 KB of RAM–an amount of memory once available only on mainframes.

A UNIX Future Led by AT&T Personal Computers?

Jean Yates joined the group for the final segment. Yates was president of Yates Ventures, a consulting group that focused on the UNIX operating system. Cheifet asked Yates to explain what UNIX was and how it compared to CP/M and MS-DOS. Yates said UNIX was another “standard operating system” that worked with a wide variety of applications and computer brands. Indeed, UNIX was unique in that it could run on anything from the IBM PC to a mainframe like the Cray supercomputer. UNIX also made it easy to connect and network different types of computer together. For example, if you had two machines that both used UNIX, the users could send email, transfer files, and even share applications between them. UNIX was also a multi-user operating system, so more than one user could access several different programs stored on the same machine using individual terminals.

Herb Lechner pointed out that UNIX originated in Bell Labs and was previously licensed only to universities and nonprofit organizations. Was UNIX now fully commercially supported? Yates said that following the breakup of the Bell System in 1982, AT&T was now permitted to sell and support the newest release of UNIX, System V, as a commercial product. That said, UNIX still needed to be “enhanced and improved” for end users, but Yates believed AT&T was making “big strides” towards that goal.

Cheifet then asked Yates to explain the difference between UNIX and XENIX. Yates said that AT&T sold two different forms of UNIX. There was the previously mentioned System V product sold directly by AT&T. Then there was the licensed UNIX source code itself, which was more expensive but allowed the purchaser to make changes to the software. Consequently, the source code was typically licensed to computer manufacturers and software companies. In the case of XENIX, Microsoft purchased the UNIX source code and “enhanced” it to run on microcomputers like the Apple Lisa, the Tandy 16/6000, and the Fortune 32:16. Yates said it was also rumored that XENIX would be sold for the IBM Personal Computer XT.

Lechner said he always associated UNIX with the PDP-11 series of minicomputers sold by Digital Equipment Corporation. He then asked Tony Fanning about his own experience with UNIX. Fanning said he’d been working with UNIX for about five years, which made him a “relative newcomer” to the operating system, although he had yet to try it on minicomputers. Fanning reiterated that presently worked mostly with MS-DOS, which he said was reputed to be moving more towards acting like UNIX. Yates added that most of the energies towards developing UNIX for microcomputers was coming from companies besides AT&T, as it again was prohibited from commercially exploiting the operating system prior to the recent deregulation. She theorized that AT&T would soon introduce its own line of UNIX-based mini- and microcomputers that offered commercial features. Right now, she said that there was still a substantial cost involved in “holding the hand” of a beginning CP/M or MS-DOS user versus UNIX.

Cheifet asked Kildall where CP/M would fit into this evolving picture. Kildall said that UNIX had been a good influence of the computer industry, especially with respect to tools and utilities. He said Digital Research was also doing work with UNIX in conjunction with Intel. Ultimately, Kildall said CP/M’s multi-tasking capabilities would prove “complementary” to what UNIX offered.

Lechner pointed out that when someone bought CP/M, they expected the operating system to remain invisible. In contrast, no two UNIX systems were alike, as each user could modify, develop, and tinker with the system software as they wished. Lechner asked Yates if that was what helped distinguish UNIX in the market. Yates replied that while CP/M was exclusively a microcomputer operating system, UNIX was derived from minicomputers and came with approximately 400 built-in programs for things like typesetting, email, text processing, unit conversion tools, and programming languages. It was by design a very big system–but also very modular. Yates said she herself deleted about two-thirds of the standard included UNIX programs because she never used them. In that sense, UNIX was a “do it yourself” operating system that required somewhat more expertise than CP/M.

Where Are They Now?

Gary Kildall and Herbert Lechner are Chronicles regulars, so I won’t delve into their post-show careers at this time. As for Tony Fanning, I could not find anything about him aside from a sparse LinkedIn page noting he was retired from Hewlett-Packard. So let’s focus this section on Apple’s Bruce Tognazzini and Jean Yates.

Tognazzini: Old Apple Designer Becomes New Apple Critic

Bruce Tognazzini joined Apple in 1978 as one of its first 100 employees. He primarily worked on user interface design during his 14 years with the company. Tognazzini actually co-authored the demo software that introduced users to the Apple II, Apple Presents…Apple. More notably, he authored Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines during the Apple II and early Macintosh eras.

After leaving Apple in 1992, Tognazzini joined Sun Microsystems and developed dozens of inventions related to human-computer interaction, including the patent for the “rolling blackout” password system commonly used on today’s mobile devices. Four years later, Tognazzini joined WedMD during its startup phase as lead designer.

Today, Tognazzini is a principal with the Nielsen Norman Group, a user interface research and consulting firm. In recent years, Tognazzini has become a notable critic of Apple’s user interface design choices, especially in the post-Steve Jobs era. For example, in a November 2015 article for Fast Company, Tognazzini and co-author Don Norman argued that Apple’s user interfaces for the iPhone and iPad were “destroying design”:

Worse, it is revitalizing the old belief that design is only about making things look pretty. No, not so! Design is a way of thinking, of determining people’s true, underlying needs, and then delivering products and services that help them. Design combines an understanding of people, technology, society, and business. The production of beautiful objects is only one small component of modern design: Designers today work on such problems as the design of cities, of transportation systems, of health care. Apple is reinforcing the old, discredited idea that the designer’s sole job is to make things beautiful, even at the expense of providing the right functions, aiding understandability, and ensuring ease of use.

Yates Pivots from UNIX to Online Wine Marketing

Jean Yates originally founded her eponymous Yates Ventures in 1978 as a market research firm supporting “open systems software.” But she best became known for her work with UNIX. After selling Yates Ventures to International Data Corporation in 1981, she stayed on as a vice president with that company and ran its UNIX division based in Palo Alto, California. She also co-authored several editions of the User Guide to the UNIX System.

A couple of years after her Chronicles appearance, Yates retired from the computer industry and decided to open a wine store in Oregon. She would own Avalon Wine in Corvallis, Oregon, for more than 25 years. In a 2013 profile written by Andy Perdue for Great Northwest Wine, Yates said she managed to put her tech experience to good use in pivoting her business to online marketing during the 1990s. By 2013, Yates sold Avalon to two of her employees and started Oregon Wine Marketing, a digital marketing firm focused on small wineries.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode was first broadcast on February 19, 1984.

- You can watch this episode at the Internet Archive.

- Although Stewart Cheifet described CP/M as “the major operating system in use today,” the market was already shifting away from Digital Research’s product. IBM’s adoption of MS-DOS–essentially a CP/M clone that was purchased and re-licensed by Microsoft–for its Personal Computer eventually led to it becoming the industry standard as other manufacturers quickly cloned IBM’s largely off-the-shelf hardware.

- Jean Yates’ prediction that AT&T would eventually enter the personal computer market with UNIX-based machines did come to pass. AT&T introduced the UNIX-based PC 7300 (also known as the AT&T UNIX PC) in March 1985, about a year after this Chronicles episode aired. Yates was quoted in the New York Times stating the AT&T machine had better specs than IBM’s own PC/AT.

- UNIX’s legacy as a proprietary operating system would eventually lead to the so-called UNIX wars, which ended with the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) largely displacing System V as an open source operating system that is still widely used today.

- As for XENIX, Microsoft effectively abandoned the project once AT&T started selling System V. Microsoft eventually sold XENIX to the Santa Cruz Operation, Inc., (SCO), which continued to market UNIX-based operating systems until 2001.

- Although Stewart Cheifet and Bruce Tognazzini used an Apple IIe in their operating system sketch, there was no mention made of the actual operating system. By this time, the Apple II line had switched from Apple DOS to ProDOS. Both were proprietary operating systems used exclusively by Apple. It was also possible to run CP/M on an Apple II using a third-party expansion card.

- According to Tognazzini’s website, he “created key clips” for the opening sequence of The Computer Chronicles. I’ll discuss that opening sequence in a future post.