Computer Chronicles Revisited 3 — Music Construction Set and the Alpha Syntauri

We begin this episode of The Computer Chronicles from February 1984 with Stewart Cheifet plunking on an unspecified model of Casiotone keyboard. Cheifet remarked to Gary Kildall, “This is an example of computer music,” which was this week’s subject. Cheifet added that the Casiotone could play special ROM chips that contain “popular songs” in electronic form.

Cheifet asked Kildall to explain how a computer makes music. Kildall replied that while the Casiotone was not a “general purpose computer,” contemporary personal computers like those manufactured by IBM and Commodore have “tone generation capability.” Essentially, the user could write a program to produce a series of tones and add information regarding their frequency and duration. Indeed, there was now software available that was comparable to word processing programs, but for music instead of text.

Cheifet then transitioned into the episode’s pre-recorded feature, which showcased the work of MIT’s Experimental Music Studio, which was founded in 1973 by Barry Vercoe. MIT itself described the studio as “the first facility to have digital computers dedicated to full time research and composition of computer music.” The Chronicles segment specifically discussed the studio’s use of computer systems to “dissect” notes into their soundwave components. A composer could then adjust the notes physical characteristics “independently and instantly.”

Specially developed musical languages allowed for the creation of music in a digital form that could then be stored on magnetic tape. This went “beyond the range” of what mechanical instruments and the human voice could accomplish, Cheifet said in narration. He concluded that the next step would be to implement “real-time production synthesis,” i.e., live performances using computer instruments. This, however, would require high-speed computers capable of performing “several hundred million calculations per second.”

Composing Music on an Apple II (with an Inexpensive Software Package)

Will Harvey and John Chowning joined Cheifet and Kildall for the next segment. Chowning, who discovered the algorithm for FM synthesis in 1967, was then the director of the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics at Stanford University. Kildall opened the segment by asking Chowning about the state of computer generated music. Chowning noted that it had been 20 years since scientists first conceived of the idea of computer music, and in recent years there had been “large-scale integration” with personal computers. Moving forward, Chowning said we could expect “more and more power in smaller and smaller units.” Practically speaking, this meant computer music that was once possible only in the laboratory could soon be put into concert halls or other small environments.

Cheifet pointed out that some people were critical of the combination of computers and music, arguing the former diminished the “human creativity” required for the latter. Cheifet asked Chowning to clarify what role computers actually played in creating music. Chowning noted that computers relied on programming languages, which themselves represented “10,000 years of man’s thought about thought.” This meant that once a computer language was involved, an individual user has “access to a degree of power and generality that was not the case with ordinary musical instruments.” He pointed to his fellow guest, Will Harvey, who managed to develop a musical composition program using just a personal computer and a programming language.

Cheifet followed up by asking if that meant computers actually helped with the “composition process.” Chowning said yes, the programming language was an “enormously rich resource” that enhanced the composition process.

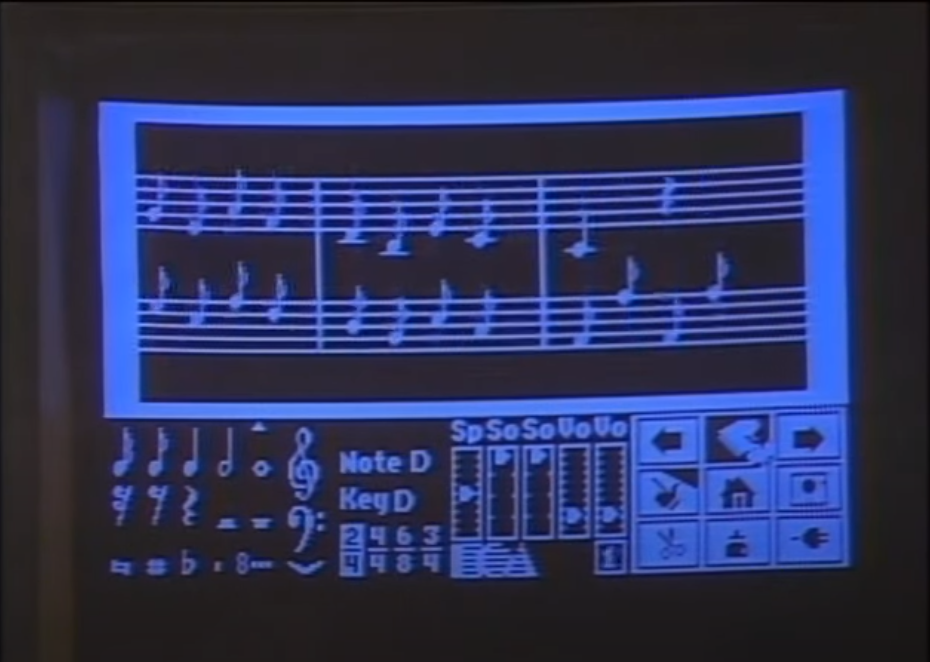

With that, Cheifet turned to Harvey, who developed Music Construction Set, a program then sold for about $40 by Electronic Arts. Harvey explained that with his program, a person who didn’t know anything about music–and may, in fact, be intimidated by learning the subject–could still create their own music using nothing more than a joystick. Cheifet then asked Harvey to demonstrate Music Construction Set using an Apple II. Essentially, the user moved a hand-shaped cursor to pick up notes and set them down on a musical staff. After setting up the notes, the user could then select various actions, such as playing the assembled composition. Harvey played a demonstration song that came bundled with the software. In response to a follow-up question, Harvey added that the notes scrolled by as they played. The composition screen was basically a digital representation of sheet music–only instead of using a pencil to erase notes, with his program you could simply move the notes around on the screen.

Kildall observed that software like Music Construction Set made learning about music more fun. Harvey noted that aside from learning how to use a joystick, which wasn’t that difficult, it was easy for users to simply play around with compositions. For example, they could make changes to works by Mozart or Bach just to see what they sounded like. Kildall asked if people actually liked to learn about music this way. Harvey said people were “overly cautions when first using a computer program.” But after about 5 or 10 minutes, they realized it was fun and they wouldn’t hurt anything.

Cheifet then chimed in, pointing out that while Music Construction Set was targeted at people who didn’t know much about music, you still had to take notes and place them on a staff. How could you do that when you didn’t know anything about music to begin with? Harvey replied the manual that came with the software explained basic music notation and how the staff works. And if the user was unsure about what a note sounded like, they could just press a key to hear any selected note.

Cheifet concluded the segment by asking John Chowning how software like Music Construction Set compared with the work he was doing at Stanford. Chowning said that it was assumed that participants in his program already understood the “abstract symbols” associated with music. Indeed, the activity at CCRMA was centered on musicians who had already studied for some considerable time and were now focused on the engineering aspects of computer music, as opposed to drafting sheet music. Nevertheless, Chowning described Harvey’s software as “interesting” and said it provided a “very accessible medium” to learn the abstract language of music notation.

Composing Music on an Apple II (with an Expensive Keyboard Attachment)

For the final segment this week, Chowning remained with Cheifet and Kildall as they welcomed Ellen Lapham, the president of Syntauri Corporation. Lapham demonstrated her company’s signature product, the Alpha Syntauri, an electronic keyboard that connected directly to the Apple II. Kildall opened by asking Lapham to explain how her product differed from Will Harvey’s Music Construction Set. Lapham quipped they were both in the music business and both used computers. But the key difference was that the Alpha Syntauri was designed to turn the personal computer into a musical instrument. It allowed the user to “play, transform sounds, compose, and even learn keyboard.”

Lapham showed how the Alpha Syntauri made it possible to use the Apple II like a record player, as composition files were stored on standard floppy disks. She demonstrated a composition that she recorded a couple of weeks earlier. The bundled software then displayed the music as it played back. Unlike Music Construction Set, which only displayed music on the staff, the Syntauri software could also display an on-screen keyboard. Lapham noted this could also be used to learn simpler songs.

Cheifet then turned to Chowning and noted the computers he used at Stanford were “so large you couldn’t bring it to the studio.” But Chowning did provide an example of the output produced at Stanford in the form of a manuscripting program developed over the past 10 years by Stanford’s Leland Smith, which made it possible to print musical compositions using a standard printer plotter. This software effectively allowed composers to self-publish their own composition.

Cheifet then introduced an audio recording provided by Chowning, which offered some examples of the “high-quality vocal synthesis” technology developed at Stanford. In simple terms, these were samples of computer-generated tracks that mimicked human singing. Chowning explained that it took researchers about six months to identify the “natural cues” that often seemed lacking in synthesized music. He demonstrated the multiple layers that the computer needed to introduce in order to produce something that sounded like natural song.

Cheifet then interjected to introduce another pre-recorded segment from the MIT Experimental Music Studio–a piano-computer duet of “Moments Musicaux,” composed by Martin Brody and accompanied on piano by David Evans.

After the musical interlude, Kildall asked Chowning if what we’d seen in computer music is still “mostly in the lab” or if it was being used in production. Chowning said that thanks to large-scale integration, computer music had found applications in industry. For instance, there were now musical synthesis algorithms that could be integrated into circuits, such as those used in Lapham’s Alpha Syntauri.

Cheifet then asked Lapham to elaborate on the use of floppy disks as a substitute for traditional music albums or cassettes. Did she see floppy disks as a new form of music publishing where people used their computers as the playback system? Lapham replied absolutely, she used floppy disks to self-publish her own compositions. The personal computer allowed her to write a song to disk and “send it to people around the world.” This enabled every musician to become a publisher. Music teachers could even publish their own material.

Cheifet ended the program by asking Chowning if he saw any “resistance” from professional musicians and composers to the use of computers, or if they actually loved this new technology. Chowning answered that “virtually everyone” who came to study music at Stanford learned about computer music. This also helped to make them exceptional programmers. In fact, Chowning said there was “very little resistance” to computer music among the younger generation–just look at what Will Harvey had done.

Harvey Stopped Building Model Trains, Started Building Software

(Editor’s Note: This section was added in November 2023 and adapted from Episode 10 of Chronicles Revisited Podcast.)

Will Harvey was born in 1967 and grew up in northern California. At the age of 12, he became interested in computers after seeing one at a friend’s house. Personal computers in the home were still a rarity in 1979, however, not to mention expensive. Nevertheless, Harvey set his sights on a Commodore PET, a business microcomputer released by Commodore International in 1977. The PET’s suggested retail price was $795, although in 1979 you could find them from some stores for around $600. Still, that was more money than the average 12-year-old made from their allowance.

So Harvey cut a deal with his parents. He’d work a summer paper route to earn half the money towards the PET, and his parents would give him the other half. After fulfilling his end of the bargain and finally bringing home a PET, Harvey embarked on his new hobby as a computer programmer. As a 1984 San Francisco Examiner profile noted, once Harvey got into programming, “He stopped building model trains.”

Programming at first did not mean developing games or entertainment software. The PET wasn’t much use for either. Harvey’s first programming endeavors focused on more practical applications. He wrote a program to help his mother, a college philosophy instructor, manage her grading system. He created another program, The Collector, to help his younger brother better organize his baseball cards and stuffed animals. Harvey even started giving other family members specially created disks as birthday presents.

Eventually, Harvey traded up from the PET to an Apple II. While still quite limited, at least the Apple could display bitmap graphics and produce some sound using a one-channel beeper speaker. With these upgrades, the now-15-year-old Harvey tried his hand at game design. After teaching himself 6502 assembly language, he created a Space Invaders-style game where the player had to kill a group of bugs that blew colorful bubbles. The bubbles would eventually hatch new bugs if not destroyed.

Harvey dubbed his finished game Lancaster. The name had nothing to do with the content of the game. He later recalled to MicroTimes that while designing a logo, he decided the letters L-A-N-C fit together nicely, and he was studying the English Wars of the Roses in school at the time, so he went with “Lancaster” after the House of Lancaster.

Naturally, once he had his game and a title, Harvey decided to find a publisher who could actually sell Lancaster*.* His first stop was Sirius Software, one of the earliest publishers of Apple II games. Harvey later recalled that he simply called up the company and asked to speak with their president. He actually got through and was invited to demo Lancaster at the company’s office in Sacramento. So Harvey took the bus to the California state capital. The meeting apparently didn’t go as well as he’d hoped, however, and he ended up selling Lancaster to a smaller publisher called Silicon Valley Systems.

Silicon Valley published a handful of Apple II and Atari 8-bit computer programs in 1982 and 1983, including Lancaster and The Collector. But the company apparently ceased active operations soon after. Harvey later bought back the rights to Lancaster but it was never re-released.

It turned out that one aspect of Lancaster—its music—would set the stage for Harvey, still in high school, to see his first major commercial success. Harvey managed to create fairly complex Baroque-style background music for Lancaster, at least by Apple II standards. But he had no prior musical training or ability. Instead, Harvey wrote simple program to convert store-bought sheet music into sounds that the Apple II could generate. After completing Lancaster, Harvey continued to fiddle with his rudimentary music-transcription program.

At some point in 1983, Harvey met with representatives from a newly established software company in San Mateo called Electronic Arts. EA was the creation of an ambitious Stanford MBA named William “Trip” Hawkins. Hawkins had been at Apple as its director of strategy and marketing. But his goal was always to build a computer game company, even before such a thing could viably exist.

EA launched its first set of games at the June 1983 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, Illinois. Among the launch titles was Bill Budge’s Pinball Construction Set, which actually predated the existence of EA. (Budge and Hawkins appeared later in the first season of Computer Chronicles to promote the program.) And while Hawkins had no interest in Will Harvey’s Lancaster game, he was interested in the music editing program. So EA signed the now-16-year-old Harvey to a royalty and distribution agreement, and he spent the next eight months refining his editor into a commercial product, which became Music Construction Set, the second in what would turn out to be four separately developed “Construction Set” titles released in EA’s early years.

Based on newspaper advertising, EA released Music Construction Set sometime in October 1983 for the Apple II and Commodore 64, with versions for the IBM PC and Atari 8-bit line hitting store shelves by early 1984. The Apple II posed a special challenge for Music Construction Set as the machine lacked a dedicated sound chip. Harvey and a colleague, Jim Nitchals, managed to work around this limitation in software and found a way to produce up to four simultaneous notes (or “voices”) using just the Apple’s built-in speaker. But this meant relying entirely on the 6502 microprocessor, which slowed the program down such that the written music notation would no longer “scroll” across the screen as Harvey intended.

But as the Apple II was expandable, a user could restore the full functionality of Music Construction Set by installing an add-on sound card called the Mockingboard. Indeed, Harvey used an Apple IIe equipped with a Mockingboard in his Chronicles demo. Some retailers even packaged Music Construction Set with a Mockingboard and external speakers for a discount.

Notwithstanding the Apple II’s limitations, Music Construction Set proved just as big a hit as Pinball Construction Set. By November 1987, the Software Publishers Association certified that Will Harvey’s program achieved “Platinum” status, indicating over 250,000 copies had been sold across all platforms. Harvey actually beat Bill Budge, whose Pinball Construction Set achieved similar status six months later. EA also released an upgraded version of the package, known as Deluxe Music Construction Set, for the Apple IIgs in 1986, although that was not programmed by Harvey.

After graduating from high school, Harvey attended Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, where he earned bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees in computer science. During his time at Stanford, Harvey used the money that he’d earned from royalties on Music Construction Set to start his own software company, Sandcastle Productions, where he continued to develop games as an independent contractor for EA.

Harvey ended up doing three games with Sandcastle. The first, Marble Madness, was a home computer port of a popular arcade game originally released by Atari and licensed to EA. Next, there was Will Harvey’s Zany Golf, a mouse-based mini-golf game released on the Apple IIgs in 1988. Finally, there was The Immortal, an isometric action puzzle-solving game. Originally developed for the Apple IIgs, The Immortal was the mostly widely ported and distributed of Harvey’s commercial products, including a 2020 re-release on the Nintendo Switch.

While The Immortal was well-received and likely sold quite well across its multiple platforms, EA wasn’t interested in making a sequel. At this point, it was 1990 and Harvey decided to shift Sandcastle’s focus from developing computer and console games to creating tools for online gaming, a market then still in its experimental infancy. Harvey recalled to video game historian Frank Cifaldi in 2005, “At the time, multiplayer games were starting to become popular over the internet, and people were using the same programming techniques that worked over [local area networks]. These techniques didn’t work so well over a high-latency network, such as the Internet.” So Sandcastle tried to develop new techniques to reduce that latency.

Whatever Harvey and his team did, it was enough to attract a buyer in the form of Adobe Systems, which acquired Sandcastle in March 1997. During this time, Harvey also served as vice president of engineering for Rocket Science Games, a short-lived video game startup that had been trying to produce more “cinematic” games. This was during a period often labeled as the “Siliwood” era, where there was an attempt to merge Silicon Valley and Hollywood through new technologies such as CD-ROM. Harvey himself said in a 1994 interview that he was working on a CD-ROM game for EA and that, “I’m on a 10-year plan to make interactive movies. But nobody really knows what that is, including me.”

As it turned out, Harvey never made that CD-ROM game or any interactive movies. After the closing of Rocket Science and the sale of Sandcastle, Harvey’s next venture was a startup called There Studios, which he founded in 1997. There’s original goal was to create a virtual world for online socializing—an idea that would later be realized by projects like Second Life. But in the early 2000s, There’s investors decided to abandon Harvey’s proto-metaverse plan and became a defense contractor selling military simulation software instead. Uninterested in that for some reason, Harvey left There in 2003 and immediately created a new startup, IMVU, to continue the dream of making his Second Life-but-not-Second Life.

Harvey actually succeeded, and IMVU is still around (as of November 2023). IMVU currently describes itself as “the world’s largest web3 social metaverse,” proving that even an old programming hat like Will Harvey can still adapt to contemporary buzzword marketing. Harvey handed over the reigns as IMVU’s CEO in 2008 but remains its chairman. In 2011, Harvey started yet another company, Finale Inventory, which in contrast to all of the web3 hoopla is a fairly conventional software-as-a-service organization focused on inventory management software. He remains CEO as of this writing.

Ellen Lapham Continues to Climb

The other product demonstrated in this episode, the Alpha Syntauri, did not appear to have as long of a shelf life as Music Construction Set. I could not find any significant references to the product after 1984, and the Syntauri Corporation itself did not seem to last past the mid-1980s.

The most notable piece of press I did find was a New Hampshire-based computer magazine called SoftSide, which reviewed the Alpha Syntauri in its October 1982 issue, about a year before Ellen Lapham appeared on Chronicles. The reviewer, Steve Birchall, compared the Alpha’s manual to a Phillip K. Dick novel (specifically, Ubik), noting that learning to use the system “requires quite a lot of homework, listening and practice, similar to learning a new word processing program.” That said, Birchall found the Alpha Syntauri “musically worthwhile” and provided features that “gave me a new freedom to jump from one sound to another instantly, which I never had with the analog equipment.” Birchall ultimately concluded the Alpha was “the way to go” for professional musicians.

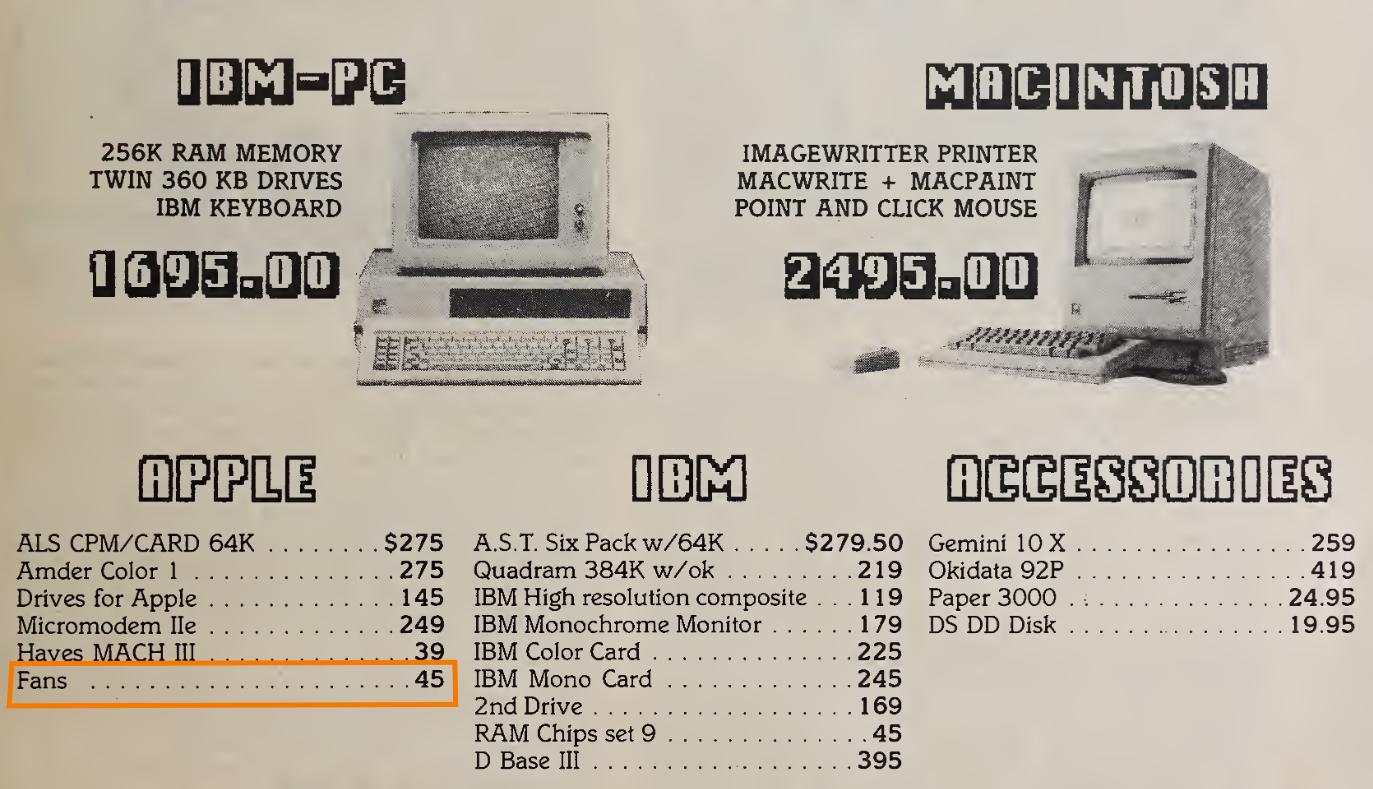

The price certainly was professional. At the time of Birchall’s review, the complete Alpha Syntauri system retailed for $1,795. And keep in mind, this was not a standalone unit. It required an Apple II computer “with monitor, one disk drive, game paddles,” and an audio system to function properly. And how much would that run you? Perusing through some of the computer store ads from that 1984 issue of MicroTimes referenced earlier, you could get an “Apple IIe package” from one retailer for $995. That would get you the computer, one disk drive, and the monitor. Not sure what a separate audio system and game paddles cost.

As for Syntauri’s president, Ellen Lapham, she’s also a Stanford graduate (she earned an MBA). And like Will Harvey, Lapham seems to have bounced between a number of founder/CEO jobs during her tech career. According to her Facebook page, she ran Award Software International, Inc., and Searchbutton Corporation. Today, she seems to have turned her attention to promoting outdoor interests, particularly mountain climbing. (She’s climbed Mount Everest twice.) Lapham is co-founder and chairperson of the board at the American Climber Science Program, a Colorado-based nonprofit organization that facilitates “research and conservation in remote and mountain environments and provide opportunities for education and true exploration.” She also co-founded the Sustainable Summits Initiative, which hosts biennial conferences that focus on developing solutions to the problems caused by human impact on mountain climates.

John Chowning’s Long Stanford Career

Finally, there is Stanford professor John Chowning. As mentioned above, Chowning invented the FM synthesis algorithm in the 1960s, essentially making him the father of the modern synthesizer. According an an online biography by Jason Ankeny, Chowning initially licensed his FM synthesis patent for one year to Yamaha. Stanford actually fired Chowning shortly thereafter, Ankeny said, due to his “meager musical output.” But after Yamaha renewed its patent license for another 10 years, Stanford “quickly rehired Chowning” and later installed him as director of the CCRMA in 1975 before awarding him a full professorship in 1979. He eventually retired from Stanford as the Osgood Hooker Professor of Fine Arts and Professor of Music.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and was recorded on December 5, 1983.

- I’m reasonably certain that the pianist David Evans featured in the MIT music segment is not the guitarist from U2 better known as the Edge.

- Another tidbit from the MicroTimes computer store ads that made me giggle: You could buy “FANS” for your Apple Computer for $45, thus thwarting Steve Jobs yet again in his quest for fanless machines.

- Ellen Lapham told her high school alumni newsletter in 2019 that she “advised” a “very young Apple Computer” back in her days as a public relations and marketing specialist.