Computer Chronicles Revisited 18 — Personal COBOL, Forth, and DR Logo

In Part 16, we saw a demonstration of Apple Logo, a computer programming language promoted as an alternative to BASIC. This next episode of The Computer Chronicles features another version of Logo–this one developed and sold by co-host Gary Kildall’s Digital Research–as well as a broader discussion of the state of computer programming languages around early 1984. The other languages presented in this episode–COBOL, Forth, and Pascal–are still in use today, even if they are not necessarily at the top of the Stack Overflow survey of most popular programming languages.

Computers Can Speak to Humans–But Not Each Other

Stewart Cheifet opened this episode by posing a simple question to Gary Kildall in French. Since Kildall didn’t speak French, he didn’t understand the question. Cheifet joked this demonstrated how a human “computer” could not understand a language different than what it was programmed with.

Cheifet asked Kildall to explain the different levels of computer programming languages. Kildall said there was basically three major “levels” of languages: (1) machine language made of up 1s and 0s, which formed the lowest level; (3) system languages like C, which were used to create applications like word processors and spreadsheets; and (3) high-level end-user languages like Fortran, COBOL, and Logo.

Cheifet then narrated our B-roll for the episode, which focused on the problems of having so many different computer languages. There was a demonstration of a “multi-lingual keyboard” that used software to translate English sounds to Japanese text. Cheifet noted this program did for human beings what most computers were incapable of doing with their own languages. Because machine code varied from one microprocessor to another, the same programming language could not be shared by two different computers. For example, Apple BASIC was not the same thing as IBM BASIC. A language customized for one computer would not run on another.

Cheifet said that like their human-language counterparts, computer programming languages differed in structure, syntax, code, and even symbols. But the lack of any standard transferrable code put the programmer at a time-consuming disadvantage: After learning to write a program for one computer, they had to rewrite it for another. And because of a computer’s wide range of applications, languages tended to be specialized–e.g., Fortran was used for science and math, COBOL for business, and Logo for education.

The more friendly that a higher-level language was for the user, the more translation it required before it could be executed at the machine level, and thus the slower it ran. In some cases, Cheifet said, the lack of speed at the machine level was a trade-off for quick interaction with the user. Adding a third layer of complexity was the assembly language required to translate higher-level programs into machine code. Conversely, programs written in assembly were faster in execution but more difficult to write. Consequently, software companies were developing more powerful “portable languages” for use in microcomputers, but as long as manufacturers designed exclusivity into their products and languages, users were faced with the same dilemma–machines that could communicate with everyone except each other.

“Exploding Myths About COBOL”

Paul O’Grady, a co-founder of Micro Focus–the sponsor for this early run of Computer Chronicles–and J. David Eisenberg joined Cheifet and Kildall in the studio. Kildall asked O’Grady about Micro Focus’ new “Personal COBOL” offering. O’Grady said his company was in the business of “exploding myths about COBOL.” He noted that mainframe users held to the myth that COBOL could not run on smaller microcomputers. And microcomputer users held to the myth that they just didn’t like COBOL. O’Grady said the goal of Personal COBOL was to differentiate between the language itself and the environment. In the past, COBOL operated exclusively in the mainframe environment, and that had led to much dissatisfaction.

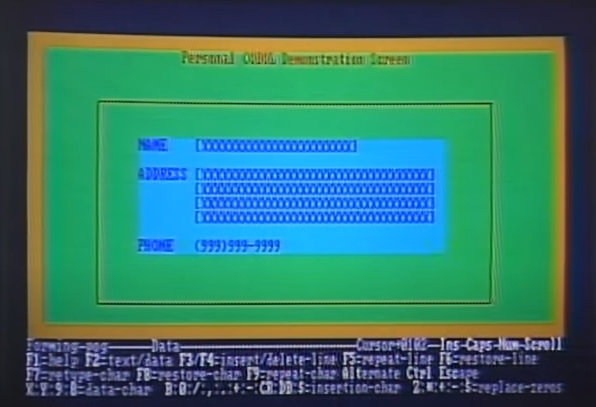

O’Grady then demonstrated Personal COBOL on an IBM Personal Computer. He described this version of COBOL as a combination of an editor, forms generator, and syntax checker. Specifically, he showed how you could generate a data-entry form in roughly five minutes.

Kildall noted that in traditional COBOL programming, you would work out all of the details that would produce this screen. But in this case, O’Grady made the screen manually by moving a cursor around, effectively the inverse of traditional COBOL. O’Grady said that was correct. With Personal COBOL, the user created the form and the software generated the COBOL code automatically.

Cheifet followed up on O’Grady’s statement that some programmers have said in the past they did not like COBOL. Why was that? O’Grady said COBOL involves a lot of detailed syntax, such as placing a period at the end of each statement, which created problems for programmers. There was also the need to define records at the start before getting into “the guts” of a program. This reflected the type of business applications that COBOL was designed for, such as data-handling and file-manipulation programs. For these kinds of applications, O’Grady said it was necessary to create the records at the start.

Cheifet then turned to Eisenberg, a senior software engineer at Apple, about his work with the Pascal programming language. What did Eisenberg like about Pascal? Eisenberg said one of the nice things about Pascal was its power of expression. In terms of a small amount of on-screen text, the user could get a “lot of power” out of Pascal. For instance, you could express a mathematical algorithm the way you think about it instead of forcing it into some other mold. Much like COBOL’s approach to business applications, Eisenberg said Pascal adopted a similar methodology for more general purpose applications.

Kildall noted that several years ago, Pascal had generated a lot of interest as an all-purpose systems language, but that seemed to be waning. Eisenberg pointed out that the inventor of Pascal, Niklaus Wirth admitted the original goal of the language was to teach people about computer science. Indeed, Wirth was now working on another language, Modula, that was supposed to take over from Pascal as a systems language.

Cheifet returned to O’Grady, asking him what he saw as the use for Personal COBOL. O’Grady said he saw Personal COBOL moving beyond the traditional business applications into more personal uses like diaries and personal filing. He also saw its potential for office automation applications, basically anything that required data handling and file maintenance. Kildall added that COBOL was not really a language meant for end users, but rather for developers who wanted to write and sell programs. O’Grady quipped that as far as he was concerned, none of the programming languages currently available were really meant for end users, including BASIC.

“When You Discuss Languages, It Almost Becomes a Religious Argument.”

For the final segment, Elizabeth Rather joined Cheifet, Kildall, and Eisenberg. Rather was president of Forth, Inc., which produced the Forth programming language. Cheifet asked Rather what made Forth unique. She said there were two things. First, it was the only programming language designed from “first principles” to work on a small computer doing interactive software development for real-time applications. Second, Forth worked on all three levels of programming that Kildall discussed during the introduction. It could work at the machine code, systems programming, and higher user levels.

Rather demonstrated Forth on an IBM Personal Computer. She noted that the operating system used to run the demo was itself written in Forth. She demonstrated a simple graphics application that generated and displayed the Forth corporate logo and performed a series of area fills.

There was then an exchange between Kildall and Rather over the combination of assembly language and Forth in the code used to produce this program. Rather clarified it was a mix of the two. With Forth, you could put in as much assembly as needed, either to control the hardware directly or to make things run faster.

For the final demo, Kildall took control of the IBM PC himself to show his company’s DR Logo. While Kildall got the program up and running, Cheifet asked Eisenberg if there would always be a number of different computer programming languages? Or would they merge into a smaller number? Eisenberg said while it would be nice to have an “ideal language,” he didn’t think that would ever happen. He reiterated how different languages were designed for different purposes. He also noted, “When you discuss languages, it almost becomes a religious argument.” But at the end of the day, a programming language was simply a tool. It would be like arguing over whether a hammer was better than a screwdriver–tell me what you wanted to do, and he would tell you which was better for that job.

With that, Kildall got DR Logo running. He noted it was an interpreted language that gave the user immediate feedback to the work they were doing. For example, if you typed FD 40 in the turtle graphics portion of Logo, the on-screen turtle moved forward by 40 steps. In contrast to this approach, other programming languages like Fortran and Pascal were compiled, meaning they did not give this type of immediate feedback. The programmer had to go through the process of editing and compiling and often a few additional steps, which required a lot of abstraction.

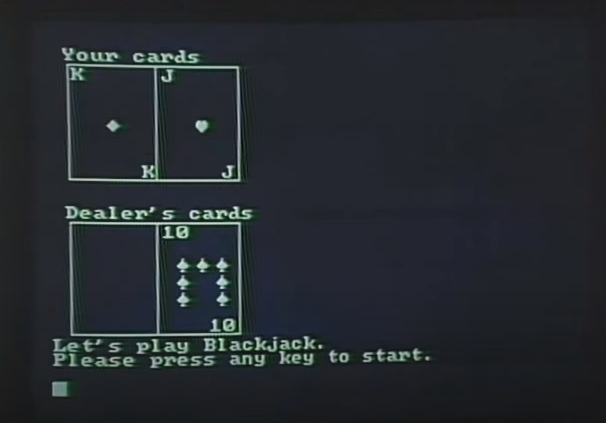

Kildall also demonstrated an application written in DR Logo, a simple blackjack game designed by a 13-year-old friend of his son. Kildall said the game was written in about 3 or 4 days and showed how you could build a program without a great deal of effort that was still interactive and graphical in nature. Eisenberg added that one of the nice things about languages like Logo was that the user could define their own words, which made the final program read closer to English.

Cheifet noted that most new computer users were exposed to BASIC as their first language. How was Logo better than BASIC? Kildall explained that BASIC was essentially derived from Fortran, the first high-level programming language, and that meant BASIC also inherited a lot of Fortran’s problems. It required a step-by-step breakdown of a problem into simple steps. That was not always the best approach for building a program. Logo, in contrast, came out of work done at MIT where the developers thought about the “problem of problem solving itself” and created a language that would suit that purpose.

Kildall said that BASIC was an easy programming language to learn but it had limitations as soon as you started to do anything complicated. Rather added that BASIC was designed for use by college undergraduate students performing simple tasks. But newer languages like Forth and Logo had the capacity to grow and learn new things, not unlike the process of teaching a small child. Kildall said Logo also provided something of a “bait and switch.” It got children interested through the turtle graphics, but behind it was a form of Lisp, another programming language that had been used for years in work on artificial intelligence and list processing. Forth and Lisp also shared some foundations.

Finally, Cheifet asked if there were any new programming languages on the horizon. Eisenberg remarked that at last count, there were about 700 or 800 known languages. But many were designed to perform a specific task or were offshoots of one of the main languages. But as long as people had ides for things they wanted to do, they would continue to invent new languages. Kildall added that once you learned one programming language, it was not very difficult to pick up other languages. The threshold was to learn that first language.

Visual Cobol and SwiftForth Carry On the Legacy

I mentioned the annual Stack Overflow survey in the introduction. This polls developers on, among other subjects, their primary programming, scripting, and markup languages. You won’t find any of the languages discussed in this Chronicles episode on that list. That’s not to say, however, that COBOL, Forth, Pascal, and even Logo are no longer in use.

To the contrary, more than 60 years after the language was first deployed, Micro Focus continues to actively develop and market COBOL. The company’s Visual Cobol 7.0 can presumably trace its lineage back to the Personal COBOL demonstrated on Chronicles. Only today’s COBOL now works with modern editors like Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code and can compile applications into more commonly used programming languages like Java.

Forth, Inc., also continues to produce its namesake programming language in more modern forms. In addition to consulting services, Forth offers SwiftForth, an integrated development environment compatible with Windows, Linux, and macOS. There are other implementations of Forth developed outside of Forth, Inc., which are commonly used in embedded computer systems.

“Computers Were Built to Make Money, Not Minds”

As discussed in my prior post on the Apple Logo episode, its famous turtle graphics lives on in the present-day Python programming language. Gary Kildall would no doubt be pleased. This episode showed Kildall’s passion for Logo as an introductory programming language for end users, and students in particular.

In an article for the June 1983 issue of Byte Magazine, Kildall and co-author David Thornburg argued that DR Logo “sets a new benchmark by which to measure the properties of useful computer languages.” They noted that DR Logo, which retailed for about $100, ran on 16-bit machines like the IBM Personal Computer and thus offered a significant advantage in terms of memory over the 8-bit Apple computers running Logo. At the same time, DR Logo was a “superset of Apple Logo,” and programs written for the former would work on the latter.

Aside from introducing kids to turtle graphics, Kildall and Thornburg said DR Logo had many other potential uses in educational applications:

In the physical sciences, Logo can be used to construct microworlds in which bodies obey different natural laws, such as gravitation. By exploring these artificial microworlds, children can develop better intuitions about the properties of their own corner of the universe.

Given Logo’s powerful list-processing capability, one would expect it to be of value in the language arts as well. To pick one simple example, suppose a child created several lists called

nouns,verbs,adjectives,articles, etc., and assigned appropriate words to each list. The word order in each list can be randomized with theshufflecommand, and a random sentence can be constructed by assembling words from each list in a syntactically correct valid order. Legitimate nonsense sentences can be automatically generated in this fashion (e.g., No yellow toad smells tall people.) while bringing the child to look at and solve the structure of English.

Later, Kildall conceded that Logo had failed to displace BASIC as the language of choice for introducing students to programming. In an unpublished manuscript for his never-completed autobiography, Kildall said he “felt the kids using BASIC on the Apple II and IBM’s new PC were being taught archaic mind tools to solve problems.” But while Logo “became popular among a largish cult of teachers that were computer literate”:

[I]n reality, most teachers found themselves racing to catch up with their brightest students and found solace in using BASIC.

This is not a comment about inadequacies in our educational system. It is a comment about the times. I expected too much of educators. I expected them to understand, in a sense, the sugar-coated concepts of LISP used in [artificial intelligence] that were embodied in the Logo language.

It was then I learned that computers were built to make money, not minds.

Notes from the Random Access File

- This episode is available at the Internet Archive and has a recording date of February 9, 1984.

- Paul O’Grady, who was described as an executive vice president of Micro Focus in this episode, eventually became CEO of the company, a role he served in until the mid-1990s.

- Elizabeth Rather was the second person to actually program in Forth. She learned Forth from its creator, Chuck Moore, who wrote in a 1991 paper that he initially hired Rather to “provide on-site support” for a computer-operated telescope using Forth in Tuscon, Arizona. Rather went on to serve as president of Forth, Inc., until her retirement in 2006.

- J. David Eisenberg worked at Apple from 1979 to 1985. He’s worked since then as an independent software developer and a computer science teacher at Evergreen Valley College in San Jose, California. You can watch some of his lectures on his YouTube channel.

- It was only touched on in the episode, but Eisenberg worked on Apple Pascal, which was produced between 1979 and 1985 for the Apple II and Apple III.

- According to a June 1982 company newsletter, Digital Research also had an agreement to sell COBOL compilers made by Micro Focus.

- If you want to hear more of Gary Kildall’s thoughts on DR Logo, he gave a lecture on the subject to the Boston Computer Society in March 1983, which has been preserved by the Computer History Museum on YouTube.

- In the previous post on Apple Logo, I mentioned Sean Tibor and Kelly Paredes’ podcast, Teaching Python. They were kind enough to discuss my post in their most recent episode.